Sound Recording Authorship, Section 203 Recapture Rights and a New Wave of Termination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

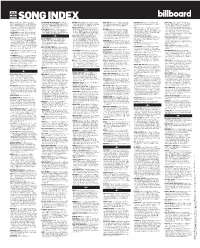

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories. -

Long Beach Dub Allstars Right Back Mp3, Flac, Wma

Long Beach Dub Allstars Right Back mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Rock / Reggae / Pop Album: Right Back Country: US Style: Reggae, Dub, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1863 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1802 mb WMA version RAR size: 1957 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 294 Other Formats: AUD AHX VQF FLAC WAV MPC MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Righteous Dub 1 Vocals – Barrington Levy 2 Rosarito My Own Life 3 Vocals [Punk Rock] – Fletcher Dragge 4 Fugazi New Sun 5 Vocals – HR* Kick Down 6 Vocals – Dangr 7 Like A Dog Sensi 8 Vocals – Tippa Irie Trailer Ras 9 Lead Guitar, Guitar [Accent] – Miguel* Pass It On 10 Vocals – Half Pint Soldiers 11 Written-By – Trad.* Saw Red 12 Mixed By – Dave AronPercussion – Butch Smalls*Producer – Lee JaffeVocals – Barrington Levy Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – SKG Music LLC Phonographic Copyright (p) – SKG Music LLC Distributed By – Universal Music & Video Distribution, Inc. Recorded At – Record Two Mendocino Recorded At – The Sound Factory Recorded At – Total Access Recording Studios Recorded At – B-Room Recorded At – The Dojo Mixed At – Total Access Recording Studios Mixed At – Track Record Mastered At – Oasis Mastering Published By – Lipstick Music Published By – Sunnylee Music Published By – Fig Publishing Published By – Trailer Ras Music Published By – Eric Wilson Publishing Published By – Mr. Cook Songs Published By – Intellect's Asylum Published By – Cliff Top Music Published By – Riley Mouse Music Published By – Samaja Music Published By – Copyright Control Published By – Emissary Publishing Published By – Lyvia's Goods Published By – Rought Estab Publishing Published By – Greensleeves Records Ltd. -

Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Bhatia, Kevin Kshitiz, "Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 441. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/441 Ozymandias: Kings without a Kingdom Ozymandias is an English sonnet written by poet Percy Shelly in 1818. The sonnet reads: “I met a traveller from an antique land who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, tell that its sculptor well those passions read which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: ’My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.”75 There are several conflicting accounts regarding Shelly’s inspiration for the sonnet, but the most widely accepted story tells that Percy Shelly was inspired by the arrival in Britain of a statute of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II. Observing the irony of a pharaoh’s statute, which was created to glorify the omnipotence of the ruler, being carried into port as a mere collectible in a museum, Shelly wrote the sonnet to summarize a particular irony that presents itself repeatedly throughout history. -

"The Covenant" Movie Their Darkest Secret Wasn't Meant to Be Shared

DVD Talk Review: Look at All the Love We Found: A Tribute to Sublime Page 1 of 5 "The Covenant" Movie Their Darkest Secret Wasn't Meant To Be Shared. In Theaters Friday. www.JoinTheCovenant.com Ads by Google - Advertise on this site Release Video Coupons Shop Reviews SUBSCRIBE Forum DVD Eggs Advertise List Games Popular Reviews Search: All Reviews For: Search Reviews » DVD Video Reviews » Look at All the Love We Found: A Tribute to Sublime Look at All the Love We Found: A Tribute to Reviews & Columns Sublime Reviews Music Video Distributors // Unrated // $19.95 // June 27, 2006 DVD TV on DVD Review by Jeffrey Robinson | posted August 17, 2006 | E-mail the Author | Start a HD DVD / Blu-ray Discussion International DVDs Theatrical Adult 1. X-3: X-Men - The Last All Male Stand Video Games 2. Lost - The Complete Features Second Season Collector Series DVDs 3. Seven Samurai: Easter Egg Database Criterion Collection (3- Interviews Disc Edition) DVD Talk TV 4. Lucky Number Slevin DVD Talk Radio 5. Thank You For Feature Articles Smoking 6. Brazil: The Criterion Columns Collection (One-Disc Anime Talk Anamorphic Reissue) The Blue Room 7. Marathon Man DVD Stalk DVD Savant C O N T E N T 8. District B13 Editor's Blog 9. Grease: Rockin' Rydell Silent DVD Edition The Movie V I D E O 10. Supernatural: The Complete First Season DVD Talk Forum Select Forum Area... In October 24th, 2005, several bands A U D I O Special Offers gathered together for a live performance at Resources the Henry Fonda Music Box in Hollywood, CA. -

A Big Back to School Music Reviewjjlqwout^

h 1 m , I f I . » W* * i l # a • 3 A BIG BACK TO SCHOOL MUSIC REVIEWJJLQWOUT^ m '¿{o x v v * * * % r < r j r ^ r ~ , ------------------- £ . - i M * V v • N 4 * f < % v t 4 2C Thursday, September 23,1999 Daily Nexus AVEDA ^Nightli) Specials! THE ART AND SCIENCE OF PURE FLOWER AND PLANT ESSENCES* < S u s k t c l *Q o -G o Monday Night: Footboii Brazilian Nights Tuesday Night: so* Night Drink Specials Prize for best outfit! Wednesday Night: $3 Monster Beers and Karioke Need A New Do? > > Be among the first to discover new talent. Book an appointment with our Thursday Night: Might Happi| Hour new stylist. With a quick head and neck massage to relieve everyday stress. And a great wash, cut and style with an Aveda professional who I price drinks knows all the trends and techniques. This kind of expertise is available only from 9-11 at Darin Jon Studio, an Aveda concept salon. So hurry and schedule an appointment today - before everyone else does ($20.°° new clients only). Hair Care | Skin Care | Makeup | Plant Pure-Fume™ | Body Care d û H f" f r v\ù i—' \rb bf~ \rb Ç f A T U N J O N j| tl. % ^ S tu d io Hair Cu||* Color Services C." |19 Chapala St • 962-1884 Sushi tZ'Qo Qo i . Horn Internet Servi N O W A V A I L A i n I s l a V i Downloads Internet information up to 100 times faster than a 28.8K modem!* Blazing download speeds up to 3,000 Kbps! f 3 0 D ay Money Back j Instant Access all the Time! ( ^ Guarantee!1 ' No phone lines, no busy signals, no waiting! Always on, always ready (t o The Best Buy on the Internet Cox@Home - your connection and ISP all in one! Three email accounts, up to 15 MB total of personal web space, remote access from any Internet connection, and unlimited usage, ¡ 5 ® all in one low monthly fee! mm « ¡ P i m S H ISS « Call 683-6651 to Order TODAY! Also available in San Roque, the Mesa, and the Westside! ¡ S ? rHSerViC8 T ü ? be aVaUabtein.aH areas C?g68S^ St ÏS iliïS S it for $l5/month. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

PDF of This Issue

Add Date Today MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Sunny, 75°F (24°C) Tonight: Partly cloudy, 62°F (17°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Rainy, windy, 71°F (22°C) Details Page 2 Volume 121, Number 49 Cambridge Massachu etts 02139 Friday October 5, 2001 IFC Elects Recruitment Chair DiF01Ja, Wulnall Begin Yardley Will Work Logan Security Work On New Rush Plans By Sandra M. Chung days, while the Task Force is For Upcoming Fall ASSOClA TE ARTS EDITOR expected to complete its investiga- Acting Governor Jane Swift tion. DiFava i replacing Joseph By Jeffrey Greenbaum appointed Colonel John DiFava of Lawless, who is being rea igned to STAFF REPORTER the Massachusetts tate Police to run security at the Port of Boston. The Interfraternity Council ha the interim position of public safety DiFava will begin his new job at elected Joshua S. Yardley '04 as director of Logan International Air- MIT after the interim period is over. Recruitment Chair for the upcoming port on October 3. DiFava was Ma sport administrators are cur- year, the first that freshmen will no recently announced as the new chief rently facing intense criticism and longer be able to live off campus. of MIT's Campus Police. scrutiny after several alleged lapses Yardley served 'as secretary of Swift al 0 recently chartered a in ecurity since the September 11 the IFC's 2002 Recruitment Com- pecial Advisory Task Force to terrorist attack. Logan Airport, mittee and is a member of the Zeta conduct a thorough investigation of which is run by Massport, has one Psi fraternity. -

CWR Sender ID and Codes

CWR Sender ID Codes CWR06-1972_Specifications_Overview_CWR_sender_ID_and_codes_2021-09-27_EN.xlsx Publisher Submitter Code Submitter Start Date End Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Number (dd/mm/yyyy) To all societies 00 Royal Flame Music Gmbh 104 00585500247 21/08/2015 Rdb Conseil Rights Management 112 00869779543 6/01/2020 Mmp.Mute.Music.Publishing E.K. 468 814224861 25/07/2019 Seegang Musik Musikverlag E.K. 772 792755298 25/07/2019 Les Editions Du 22 Decembre 22D 450628759 4/11/2010 3tone Publishing Limited 3TO 1050225416 25/09/2020 4AD Music Limited 4AD 293165943 15/03/2010 5mm Publishing 5MM 00492182346 22/11/2017 AIR EDEL ASSOCIATES LTD AAL 69817433 7/01/2009 Ceg Rights Usa AAL 711581465 17/12/2013 Ambitious Media Productions AAP 00868797449 31/08/2021 Altitude Balloon AB 722094072 6/11/2013 Abc Digital Distribution Limited ABC 00599510310 8/06/2020 Editions Abinger Sprl ABI 00858918083 23/11/2020 Abkco Music Inc ABM 00056388746 21/11/2018 ABOOD MUSIC LIMITED ABO 420344502 31/03/2009 Alba Blue Music Publishing ABP 00868692763 2/06/2021 Abramus Digital Servicos De Identificacao De Repertorio ABR 01102334131 16/07/2021 Ltda Absilone Technologies ABS 00546303074 5/07/2018 Almo Music of Canada AC 201723811 1/08/2001 2/10/2006 Accorder Music Publishing America ACC 606033489 5/09/2013 Accorder Music Publishing Ltd ACC 574766600 31/01/2013 Abc Frontier Inc ACF 01089418623 20/07/2021 Galleryac Music ACM 00600491389 24/04/2017 Alternativas De Contenido S L ACO 01033930195 17/12/2020 ACTIVE MUSIC PUBLISHING PTY LTD ACT 632147961 16/11/2016 Audiomachine -

Hercules Returns Music Credits

Composer Contemporary Footage Philip Judd Music Co-ordinator Gary Hardman Music Licensing Christine Woodruff Music Video Director Mark Hartley - Music - "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round The Old Oak Tree" Written by I. Levine/L. Russell Brown (Peermusic) "The Great Pretender" Written by Buck Ram (Peermusic) "Physical" Written by T. Shaddick/S. Kipner (Stephen Kipner Music/Terry Shaddick Music/MCA Gilby) "My Way" Written by P. Anka/J. Revaux/C. Francoise/G. Thibault (MCA Music) "Macho Man" Written by H. Belolo/V. Willis/B. Whitehead/J. Marali (Black Scorpio/AMCOS) "Since I Don't Have You" Written by Beaumont/Vogel/Verscharen/Lester/Taylor/Rock/Martin (Peermusic) "I Know What Boys Like" Written by C. Butler (Mushroom Music Pty Ltd) "Hercules Rap" Written and Performed by Des Mangan Music by Phil Rigger Original Italian film (title not mentioned in tail credits): Music Composed and Conducted by Piero Umiliani Music recorded by Firmamento, Rome (As per the credit that appears in the film within the film): The film explains the music in the film by having Bruce Spence’s character work a record player: Soundtrack: The soundtrack was never given a full-blooded commercial release, but copies did find their way into the marketplace to cater for cult enthusiasts. It was allegedly “based on the feature film”, but featured more Des Mangan and Phil Rigger than Phil Judd: CD Screentrax/Polydor 5212022 1993 Includes dialogue from the film. Produced and Arranged by: Phil Rigger Recorded at Fineline Studio, Randwick Engineered and recorded by Phil Rigger Assisted by Keith Cooper Mastered at 301 Studios, Sydney by Steve Smart Project co-ordinators: Screensong Pty. -

Poets on Punk Libertines in Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk ©2019 Jet-Tone Press the Ante-Room All Rights Reserved

Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk Libertines in Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk ©2019 Jet-Tone Press the Ante-Room All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, of Love: mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Poets on Punk Published by Jet-Tone Press 3839 Piedmont Ave, Oakland, CA 94611 www.Jet-Tone.press Cover design by Joel Gregory Design by Grant Kerber Edited by ISBN: 978-1-7330542-0-1 Jamie Townsend and Grant Kerber Special thanks to Sara Larsen for the title Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love (taken from Sara’s book The Riot Grrrl Thing, Roof Books, 2019), Joel Gregory for the cover, Michael Cross for the extra set of eyes, and Wolfman Books for the love and support. Jet - Tone ©2019 Jet-Tone Press, all rights reserved. Bruce Conner at Mabuhay Gardens 63 Table of Contents: Jim Fisher The Dollar Stop Making Sense: After David Byrne 68 Curtis Emery Introduction 4 Jamie Townsend & Grant Kerber Iggy 70 Grant Kerber Punk Map Scream 6 Sara Larsen Landscape: Los Plugz and Life in the Park with Debris 79 Roberto Tejada Part Time Punks: The Television Personalities 8 Rodney Koeneke On The Tendency of Humans to Form Groups 88 Kate Robinson For Kathleen Hanna 21 Hannah Kezema Oh Bondage Up Yours! 92 Jamie Townsend Hues and Flares 24 Joel Gregory If Punk is a Verb: A Conversation 99 Ariel Resnikoff & Danny Shimoda The End of the Avenida 28 Shane Anderson Just Drifting -

Classement Des 200 Premiers Singles Fusionnés Par Gfk Année 2012

Classement des 200 premiers Singles Fusionnés par GfK année 2012 Rang Artiste Titre Label Editeur Distributeur Physique Distributeur Numérique Genre 1 MICHEL TELO AI SE EU TE PEGO ULM MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 2 GOTYE SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW CASABLANCA MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY POP ROCK 3 CARLY RAE JEPSEN CALL ME MAYBE INTERSCOPE RECORDS POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION POLYDOR VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 4 PSY GANGNAM STYLE ULM MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 5 ADELE SKYFALL Beggars Naïve NAIVE BEGGARD GROUP / XL RECORDING INDE 6 LYKKE LI I FOLLOW RIVERS WEA WEA WARNER MUSIC FRANCE WARNER MUSIC FRANCE VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 7 LANA DEL REY VIDEO GAMES POLYDOR POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION POLYDOR VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 8 SHAKIRA JE LAIME A MOURIR Norte JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC JIVE EPIC GROUP VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 9 SEXION D ASSAUT AVANT QU ELLE PARTE Jive Epic JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC JIVE EPIC GROUP VARIETE FRANCAISE 10 RIHANNA DIAMONDS DEF JAM FRANCE Def Jam Recordings France UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION DEF JAM VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 11 ASAF AVIDAN THE MOJOS ONE DAY RECKONING SONG Columbia Deutschland JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC COLUMBIA GROUP VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 12 BIRDY SKINNY LOVE WEA WEA WARNER