Estimating Song Composition Year Using Chord Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting Started with the Tonalities Music Analysis Software

Getting Started with the Tonalities music analysis software Anthony Pople, University of Nottingham, March 2002 (v6.25/03) The support of the AHRB for the Tonalities project is gratefully acknowledged. Overview This software is part of a larger project that lays stress on the multiplicity of tonal systems in music, focusing particularly on Western music of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It allows you to analyse passages of music in terms of differing tonal systems that may be configured to a high level of detail from a range of supplied options. To use the software effectively, it is important to have an understand of the basic concepts of the underlying theory, above all: · segmentation · prolonging gamut · connective gamut · the distinction between spelled and unspelled matches of chords and gamuts · the distinction between functional and inclusive chords and gamuts These concepts are explained briefly in what follows, but it is not the purpose of the guide to present the music theory component of the Tonalities project in full. The remainder of this user guide also assumes you are familiar to some extent with Microsoft Windows and Microsoft Excel. The software has been developed in Excel 97 and will not run under earlier versions (though it seems to run under later versions up to and including Excel 2002 – the version supplied in Office XP). I have run it under Windows 98 and Windows Me, though not Windows NT, 2000 or XP. Installing the software If the software has been pre-installed, please skip this section. The Tonalities software is supplied as an Add-In to Microsoft® Excel, running under Microsoft® Windows®. -

Impro-Visor Tutorial

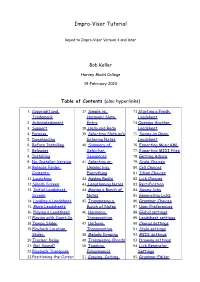

Impro-Visor Tutorial keyed to Impro-Visor Version 4 and later Bob Keller Harvey Mudd College 19 February 2010 Table of Contents (also hyperlinks) 1. Copyright and 37. Simple vs. 73. Starting a Fresh Trademark Harmonic Note Leadsheet 2. Acknowledgment Entry 74. Opening Another 3. Support 38. Undo and Redo Leadsheet 4. Purpose 39. Selecting Slots w/o 75. Saving an Open 5. Downloading Entering Notes Leadsheet 6. Before Installing 40. Summary of 76. Exporting MusicXML 7. Releases Selection 77. Exporting MIDI Files 8. Installing Sequences 78. Getting Advice 9. No-Installer Version 41. Selecting or 79. Scale Choices 10. Release Folder Unselecting 80. Cell Choices Contents Everything 81. Idiom Choices 11. Launching 42. Adding Rests 82. Lick Choices 12. Splash Screen 43. Lengthening Notes 83. Rectification 13. Initial Leadsheet 44. Moving a Bunch of 84. Saving licks Screen Notes 85. Generating Licks 14. Loading a Leadsheet 45. Transposing a 86. Grammar Choices 15. More Leadsheets Bunch of Notes 87. User Preferences 16. Playing a Leadsheet 46. Harmonic 88. Global settings 17. Playing with Count-In Transposition 89. Leadsheet settings 18. Tempo Slider 47. Uniform 90. Chorus settings 19. Playback Location Transposition 91. Style settings Slider 48. Melody Drawing 92. MIDI settings 20. Tracker Delay 49. Transposing Chords 93. Drawing settings 21. Got Sound? 50. Toggling 94. Lick Generator 22. Playback Transpose Enharmonics Settings 23.Positioning the Cursor 51. Copying, Cutting 95. Grammar Editor on the Staff and Pasting 96. Grammar Learning 24. Slots Melodies 97. Solo Generator 25. Changing the Slot 52. Cutting and Pasting 98. Style editor Spacing Across Leadsheets 99. -

Logic-Based Modelling of Musical Harmony for Automatic Characterisation and Classification

Logic-based Modelling of Musical Harmony for Automatic Characterisation and Classification Amélie Anglade Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science Queen Mary, University of London January 2014 2 I, Amélie Anglade, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: January 29, 2014 Details of collaboration and publications: All collaborations and earlier publications that have influenced the work and writing of this thesis are fully detailed in Section 1.4. 3 Abstract Harmony is the aspect of music concerned with the structure, progression, and relation of chords. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices. -

Modal Prolongational Structure in Selected Sacred Choral

MODAL PROLONGATIONAL STRUCTURE IN SELECTED SACRED CHORAL COMPOSITIONS BY GUSTAV HOLST AND RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS by TIMOTHY PAUL FRANCIS A DISSERTATION Presented to the S!hoo" o# Mus%! and Dan!e and the Graduate S!hoo" o# the Un%'ers%ty o# Ore(on %n part%&" f$"#%""*ent o# the re+$%re*ents #or the degree o# Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy ,une 2./- DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: T%*othy P&$" Fran!%s T%t"e0 Mod&" Pro"on(ation&" Str$!ture in Se"e!ted S&!red Chor&" Co*)osit%ons by Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s T %s d%ssertat%on has been ac!e)ted and ap)ro'ed in part%&" f$"#%""*ent o# the re+$%re*ents for the Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy de(ree in the S!hoo" o# Musi! and Dan!e by0 Dr1 J&!k Boss C &%r)erson Dr1 Ste) en Rod(ers Me*ber Dr1 S &ron P&$" Me*ber Dr1 Ste) en J1 Shoe*&2er Outs%de Me*ber and 3%*ber"y Andre4s Espy V%!e President for Rese&r!h & Inno'at%on6Dean o# the Gr&duate S!hoo" Or%(%n&" ap)ro'&" signatures are on f%"e w%th the Un%'ersity o# Ore(on Grad$ate S!hoo"1 Degree a4arded June 2./- %% 7-./- T%*othy Fran!%s T %s work is l%!ensed under a Creat%'e Co**ons Attr%but%on8NonCo**er!%&"8NoDer%'s 31. Un%ted States L%!ense1 %%% DISSERTATION ABSTRACT T%*othy P&$" Fran!%s Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy S!hoo" o# Musi! and Dan!e ,une 2./- T%t"e0 Mod&" Pro"on(ation&" Str$!ture in Se"e!ted S&!red Chor&" Co*)osit%ons by Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s W %"e so*e co*)osers at the be(%nn%n( o# the t4entieth century dr%#ted away #ro* ton&" h%erar! %!&" str$!tures, Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s sought 4ays o# integrating ton&" ideas w%th ne4 mater%&"s. -

Music-Theory-For-Guitar-4.9.Pdf

Music Theory for Guitar By: Catherine Schmidt-Jones Music Theory for Guitar By: Catherine Schmidt-Jones Online: < http://cnx.org/content/col12060/1.4/ > This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Catherine Schmidt-Jones. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Collection structure revised: September 18, 2016 PDF generated: August 7, 2020 For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see p. 73. Table of Contents 1 Learning by Doing: An Introduction ............................................................1 2 Music Theory for Guitar: Course Introduction ................................................7 3 Theory for Guitar 1: Repetition in Music and the Guitar as a Rhythm Instrument ...................................................................................15 4 Theory for Guitar 2: Melodic Phrases and Chord Changes .................................23 5 Theory for Guitar 3: Form in Guitar Music ...................................................31 6 Theory for Guitar 4: Functional Harmony and Chord Progressions ........................37 7 Theory for Guitar 5: Major Chords in Major Keys ..........................................41 8 Theory for Guitar 6: Changing Key by Transposing Chords ................................53 9 Theory for Guitar 7: Minor Chords in Major Keys ..........................................59 10 Theory for Guitar 8: An Introduction to Chord Function in Minor Keys -

Notes for the Beginning Ukulele Player an Introduction to Basic Music Theory for the Ukulele

Notes for the beginning ukulele player An introduction to basic music theory for the ukulele www.lakesidepress.com/UkeSyllabus.pdf By Larry Martin [email protected] Notes for the beginning ukulele player An introduction to basic music theory for the ukulele www.lakesidepress.com/UkeSyllabus.pdf By Larry Martin [email protected] First placed online June 27, 2016 Last revision September 25, 2020 http://www.lakesidepress.com/UkeSyllabus.pdf Lakeside Press The Villages, FL 32163 First, Take the Uke Quiz If you score 16 or better in this 20-question quiz (without looking up the answers), you are fairly knowledgeable about uke music theory. You can use the Syllabus as a refresher, and perhaps pick up a few new things. If the information asked in these questions simply doesn’t hold any interest, then this Syllabus is not for you. If, however, you have a moderate to low score and you find the questions interesting, then you should benefit from the Syllabus. Finally, if you don’t like quizzes, or find them intimidating, but want to learn basic music theory, then skip to the Preface. (And if Prefaces bore you, skip that and go right to the Table of Contents, page 9). 1. The notes of the F chord, as shown below on the fret board (reading left to right), are: a) G-C-F-A b) A-C-F-A c) G-C-F#-A d) G#-C-F-A 2. The notes of the G chord as shown below on the fret board (reading left to right), are: a) G-D-G-B b) G-D-F#-Bb c) G-D-G-Bb d) G-D#-G-Bb 1 3. -

Impro-Visor Tutorial Bob Keller Harvey Mudd College 13 May 2008 (Keyed to Version 3.36)

Impro-Visor Tutorial Bob Keller Harvey Mudd College 13 May 2008 (keyed to Version 3.36) Welcome to Impro-Visor, a program to help musicians construct melodies similar to ones that might be improvised over given songs. With Impro-Visor, you can playback your melodies as soon as you enter them, with automatically generated rhythm-section accompaniment. In addition to this aural feedback, you can also get visual feedback that will help you learn which notes sound the best over which chords. You can also use Impro- Visor for play-along practice, notation, transcription and song composition. Table of Contents 1. Distribution folder 32. Generating to the chorus 63. Transferring melody and chords 2. Starting the program end back 3. Loading an existing 33. Undoing entries 64. Summary of key stroke commands leadsheet 34. Saving licks 65. Drawing feature 4. Tutorial exercise 35. Avoiding saving duplicates 66. Uneven chord spacing 5. Playing a leadsheet 36. Touching up melodies 67. Aligning chords to slots 6. Controlling playback 37. Copying, cutting and 68. Leadsheet textual editor 7. Positioning the mouse on pasting melodies 69. File saving the staff 38. Note coloration 70. MIDI file saving 8. Slots 39. Note entry parallax 71. Mixer button 9. Entering notes 40. Tracker delay 72. Mixer sliders 10. Shortening notes 41. Transpose playback 73. MIDI recording 11. Making corrections 42. Key signature 74. Preference dialogs 12. Selecting slots without 43. Time signature 75. Global settings entering note 44. Adjusting the layout 76. Leadsheet settings 13. Summary of selection 45. Freezing and thawing 77. Chorus settings sequences 46. -

Music Theory Piano

Music Theory For Piano Music Theory Piano Major Scales: To figure out the Natural Minor scales, just look at equivalent major scale. For example the notes of the scale of C major, when started on A equals the key of A minor. It is said that C's equivalent minor is A, G's equivalent minor is E, F's equivalent minor is D and so on. To find the equivalent minor key, step back two notes from the root note of the major key. In the key of A major the root note is A, step back from A to G#, then to F# which is its relative minor. In C, step back to B, then to A which is its relative minor. Page 1 Music Theory For Piano Major Scale Pattern: W = Whole Step, 1/2 = Half Step Natural Minor Scale Pattern: Harmonic Minor Scale Pattern: Same as the Natural Minor, but without the flattened seventh. Melodic Minor Scale Pattern Ascending and Descending: The Ascending Melodic Minor scale is basically the major scale with a flattened third. The Descending Melodic Minor scale is simply the Natural Minor scale. Page 2 Music Theory For Piano Scale Note Names: (Example C Major) C D E F G A B Tonic Supertonic Mediant Subdominant Dominant Submediant Leading Note Doh Ray Me Fah Soh Lah Ti Key Signatures Here you can see the relationship between major and minor keys. Page 3 Music Theory For Piano Intervals Intervals are the space between two notes on the keyboard. The intervals are classified by their tonal quality with relation to the tonic note. -

Music Theory Contents

Music theory Contents 1 Music theory 1 1.1 History of music theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Fundamentals of music ........................................ 3 1.2.1 Pitch ............................................. 3 1.2.2 Scales and modes ....................................... 4 1.2.3 Consonance and dissonance .................................. 4 1.2.4 Rhythm ............................................ 5 1.2.5 Chord ............................................. 5 1.2.6 Melody ............................................ 5 1.2.7 Harmony ........................................... 6 1.2.8 Texture ............................................ 6 1.2.9 Timbre ............................................ 6 1.2.10 Expression .......................................... 7 1.2.11 Form or structure ....................................... 7 1.2.12 Performance and style ..................................... 8 1.2.13 Music perception and cognition ................................ 8 1.2.14 Serial composition and set theory ............................... 8 1.2.15 Musical semiotics ....................................... 8 1.3 Music subjects ............................................. 8 1.3.1 Notation ............................................ 8 1.3.2 Mathematics ......................................... 8 1.3.3 Analysis ............................................ 9 1.3.4 Ear training .......................................... 9 1.4 See also ................................................ 9 1.5 Notes ................................................ -

The 11 Chords of Barbershop

The 11 Chords of Barbershop Simon Rylander ([email protected]) 2008-03-31 1 INTRODUCTION Abstract In contestable Barbershop singing, only a particular set of chords are allowed, while other chords are against the rules. There are four voices, and with these, you can only form a limited number of chords. That means that you can't make any changes to your contestable arrangements without being extremely aware of what the result will be. That also means that if you want to become a Barbershop arranger, you have to know a lot of harmony theory to be able to understand what you're doing, and why. 1 Introduction So what is it that makes certain chords more appropriate than others? It's probably better to ask the question: What is a 'chord'? Are all possible four- key combinations on a piano called a chord? If you ask a jazz musician, he will probably answer yes, but in Barbershop singing it's dierent. A barbershop chord is a combination of frequencies with a mathematical relation. When you sing two notes that has frequencies with a mathematical relation, you will experience the "lock n' ring" phenomenon between them since they will amplify the same overtones. If you for example sing a note with a certain frequency X, and then add another voice singing a note with the double frequency 2X, he will sing what we call an octave to the rst note. To shape a chord with four unique notes, all notes must have dierent frequencies between 1X and 2X where the frequency X is the frequency of the root (this explanation is simplied to only cover one octave, but in theory you can double/half the frequency of any of the notes to the octave of choice). -

Oct 2 6 1995

Representing Musical Knowledge by Damon Matthew Horowitz B.A. Columbia University 1993 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 1995 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995 All Rights Reserved Signature of Author Progra 1 - . ugust 11, 1995 Certified by Toa Machover Associate Professor of Music and Media Program in Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Stephen A. Benton, Ph.D. Chairperson Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Program in Media Arts and Sciences ASSACHUSETTS INSTTUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 2 6 1995 LIBRARIES Representing Musical Knowledge by Damon Matthew Horowitz B.A. Columbia University 1993 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning on August 11, 1995 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Abstract This thesis presents an approach to building more intelligent computer music systems. Motivated by the shortcomings of previous systems, I maintain that an enumeration and quantification of musical common sense concepts is necessary for the construction of musically intelligent systems. Demonstrating this approach, a computer system for analyzing and generating improvisational jazz solos has been designed as an initial exploration into the quantification of musical intelligence. The system development has concentrated upon the creation of a knowledge representation and control structure as a model of improvisation in this domain. The design of an architecture to organize and manipulate musical knowledge is influenced by the Society of Mind approach of [Minsky 86], and the spreading activation networks of [Maes 89].