Prospects for Unseen Planets Beyond Neptune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

Unseen 'Planetary Mass Object' Signalled by Warped Kuiper Belt 22 June 2017, by Daniel Stolte

Unseen 'planetary mass object' signalled by warped Kuiper Belt 22 June 2017, by Daniel Stolte orbital tilts (inclinations) that average out to what planetary scientists call the invariable plane of the solar system, the most distant of the Kuiper Belt's objects do not. Their average plane, Volk and Malhotra discovered, is tilted away from the invariable plane by about eight degrees. In other words, something unknown is warping the average orbital plane of the outer solar system. "The most likely explanation for our results is that there is some unseen mass," says Volk, a postdoctoral fellow at LPL and the lead author of the study. "According to our calculations, something A yet to be discovered, unseen "planetary mass object" as massive as Mars would be needed to cause the makes its existence known by ruffling the orbital plane of warp that we measured." distant Kuiper Belt objects, according to research by Kat Volk and Renu Malhotra of the UA's Lunar and Planetary The Kuiper Belt lies beyond the orbit of Neptune Laboratory. The object is pictured on a wide orbit far and extends to a few hundred Astronomical Units, beyond Pluto in this artist's illustration. Credit: Heather or AU, with one AU representing the distance Roper/LPL between Earth and the sun. Like its inner solar system cousin, the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the Kuiper Belt hosts a vast number of minor planets, mostly small icy bodies (the An unknown, unseen "planetary mass object" may precursors of comets), and a few dwarf planets. lurk in the outer reaches of our solar system, according to new research on the orbits of minor For the study, Volk and Malhotra analyzed the tilt planets to be published in the Astronomical angles of the orbital planes of more than 600 Journal. -

1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects - a Review Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract Our understanding of the history of the solar system has undergone a revolution in recent years, owing to new theoretical insights into the origin of Pluto and the discovery of the Kuiper belt and its rich dynamical structure. The emerging picture of dramatic orbital migration of the planets driven by interaction with the primordial Kuiper belt is thought to have produced the final solar system architecture that we live in today. This paper gives a brief summary of this new view of our solar system's history, and reviews the astronomical evidence in the resonant populations of the Kuiper belt. Introduction Lying at the edge of the visible solar system, observational confirmation of the existence of the Kuiper belt came approximately a quarter-century ago with the discovery of the distant minor planet (15760) Albion (formerly 1992 QB1, Jewitt & Luu 1993). With the clarity of hindsight, we now recognize that Pluto was the first discovered member of the Kuiper belt. The current census of the Kuiper belt includes more than 2000 minor planets at heliocentric distances between ~30 au and ~50 au. Their orbital distribution reveals a rich dynamical structure shaped by the gravitational perturbations of the giant planets, particularly Neptune. Theoretical analysis of these structures has revealed a remarkable dynamic history of the solar system. The story is as follows (see Fernandez & Ip 1984, Malhotra 1993, Malhotra 1995, Fernandez & Ip 1996, and many subsequent works). -

Orbital Resonances and Chaos in the Solar System

Solar system Formation and Evolution ASP Conference Series, Vol. 149, 1998 D. Lazzaro et al., eds. ORBITAL RESONANCES AND CHAOS IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Blvd, Houston, TX 77058, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Long term solar system dynamics is a tale of orbital resonance phe- nomena. Orbital resonances can be the source of both instability and long term stability. This lecture provides an overview, with simple models that elucidate our understanding of orbital resonance phenomena. 1. INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of resonance is a familiar one to everybody from childhood. A very young child is delighted in a playground swing when an older companion drives the swing at its natural frequency and rapidly increases the swing amplitude; the older child accomplishes the same on her own without outside assistance by driving the swing at a frequency twice that of its natural frequency. Resonance phenomena in the Solar system are essentially similar – the driving of a dynamical system by a periodic force at a frequency which is a rational multiple of the natural frequency. In fact, there are many mathematical similarities with the playground analogy, including the fact of nonlinearity of the oscillations, which plays a fundamental role in the long term evolution of orbits in the planetary system. But there is also an important difference: in the playground, the child adjusts her driving frequency to remain in tune – hence in resonance – with the natural frequency which changes with the amplitude of the swing. Such self-tuning is sometimes realized in the Solar system; but it is more often and more generally the case that resonances come-and-go. -

Download PDF Program & Abstracts

Program Schedule and Abstract Book 2016 DDA Meeting May 22 - 26, 2016 The Program Report was last updated May 14, 2016 at 01:12 AM EDT. To view the most recent meeting schedule online, visit https://dda47.abstractcentral.com/planner.jsp Sunday, May 22, 2016 You have nothing scheduled for this day Monday, May 23, 2016 Time Session or Event Info 9:00 AM-9:10 AM, Wilson Hall 126 (Vanderbilt University), 100. Welcome Address: Kelly Holly-Bockelmann (DDA Chair), Oral Session 9:10 AM-10:40 AM, Wilson Hall 126 (Vanderbilt University), 101. Planet Formation and Migration, Oral Session, Chair: Renu Malhotra, [email protected], Univ. of Arizona 101.01. Origins of Hot Jupiters, Revisited K. Batygin; P. 9:10-9:25 AM Bodenheimer; G. Laughlin 101.02. The In Situ Formation of Giant Planets at Short Orbital 9:25-9:40 AM Periods A.C. Boley; B. Gladman; A. Granados Contreras 101.03. Kepler-223: A Resonant Chain of Four Transiting, Sub- 9:40-9:55 AM Neptune Planets S. Mills; D.C. Fabrycky; C. Migaszewski; E.B. Ford; E. Petigura; H.T. Isaacson 101.04. On the Nature and Timing of Giant Planet Migration in the 9:55-10:10 AM Solar System C.B. Agnor 101.05. WASP-47: a Hot Jupiter with Close Friends J. Becker; F.C. 10:10-10:25 AM Adams 101.06. Dynamical Origins of the Kepler Dichotomy C. Spalding; K. 10:25-10:40 AM Batygin 11:10 AM-12:30 PM, Wilson Hall 126 (Vanderbilt University), 102. Tidal Dynamics and Moon Formation, Oral Session, Chair: Alice Quillen, [email protected], Univ. -

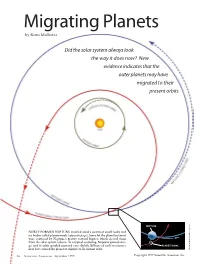

Migrating Planets Migrating Scientific American by Renumalhotra May Havecaused Theplanettomigrateitscurrent Orbit

Migrating Planets by Renu Malhotra Did the solar system always look the way it does now? New evidence indicates that the outer planets may have migrated to their present orbits NEPTUNE ) inset NEWLY FORMED NEPTUNE traveled amid a swarm of small rocky and icy bodies called planetesimals (opposite page). Some hit the planet but most were scattered by Neptune’s gravity toward Jupiter, which ejected them from the solar system (above). In a typical scattering, Neptune gained ener- gy, and its orbit spiraled outward very slightly. Billions of such encounters PLANETESIMAL may have caused the planet to migrate to its current orbit. JANA BRENNING; DON ( DIXON 56 Scientific American September 1999 Copyright 1999 Scientific American, Inc. n the familiar visual renditions of the solar that the planets were “born” in the orbits that system, each planet moves around the sun we now observe. I in its own well-defined orbit, maintaining a Certainly it is the simplest hypothesis. Mod- respectful distance from its neighbors. The ern-day astronomers have generally presumed planets have maintained this celestial merry-go- that the observed distances of the planets from round since astronomers began recording their the sun indicate their birthplaces in the solar motions, and mathematical models show that nebula, the primordial disk of dust and gas that this very stable orbital configuration has existed gave rise to the solar system. The orbital radii ON for almost the entire 4.5-billion-year history of of the planets have been used to infer the mass DIX the solar system. It is tempting, then, to assume distribution within the solar nebula. -

50Th Anniversary Science Symposium

The Lunar and Planetary Institute presents its: 50th Anniversary Science Symposium March 17, 2018 USRA - Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston, TX 77058 Inspiration and Exploration Since 1968 Dear Friends and Colleagues, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to our 50th Anniversary Science Symposium. The original Lunar Science Institute (LSI) was established in 1968 to provide a base for non-NASA scientists, encouraging them to visit the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, and use its laboratories, lunar photographs, and rock samples. President Lyndon Johnson announced the formation of the LSI during a historic speech, in which he noted that “This new institute is a center of research designed specifically for the age of space.....we will strengthen the co-operation between NASA and our universities. And we will set new patterns of scientific co-operation which will have profound effects on man’s knowledge of his universe.” This institute has been fulfilling President Johnson’s charge ever since. After Apollo, NASA asked the institute to expand its portfolio to the entire Solar System, and in 1978 the Lunar Science Institute (LSI) became the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI). The current LPI provides an academic atmosphere that serves as a focal point for lunar and planetary science activities, and as a forum to encourage participation of US and international scientists in NASA’s Planetary Science Division programs. We continue to maintain a close working relationship with the Johnson Space Center, especially the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) Division. This Symposium has two goals: first, to highlight some of the exciting discoveries that have been made during the last five decades of planetary exploration; and second, to celebrate the LPI’s contributions during this time. -

Dynamics of the Kuiper Belt

To appear in Protostars and Planets IV Preprint (Jan 1999): http://www.lpi.usra.edu/science/renu/home.html DYNAMICS OF THE KUIPER BELT Renu Malhotra (1), Martin Duncan (2), and Harold Levison (3) (1) Lunar and Planetary Institute, (2) Queen’s University, (3) Southwest Research Institute Abstract. Our current knowledge of the dynamical objects (KBOs) have been discovered - a sufficiently large structure of the Kuiper Belt is reviewed here. Numeri- number that permits first-order estimates about the mass cal results on long term orbital evolution and dynamical and spatial distribution in the trans-Neptunian region. A mechanisms underlying the transport of objects out of the comparison of the observed orbital properties of these ob- Kuiper Belt are discussed. Scenarios about the origin of jects with theoretical studies provides tantalizing clues to the highly non-uniform orbital distribution of Kuiper Belt the formation and evolution of the outer Solar system. objects are described, as well as the constraints these pro- Other chapters in this book describe the observed physi- vide on the formation and long term dynamical evolution cal and orbital properties of KBOs (Jewitt and Luu) and of the outer Solar system. Possible mechanisms include their collisional evolution (Farinella et al); here we focus an early history of orbital migration of the outer planets, on the dynamical structure of the trans-Neptunian region a mass loss phase in the outer Solar system and scatter- and the dynamical evolution of bodies in it. The outline ing by large planetesimals. The origin and dynamics of of this chapter is as follows: in section II we review nu- the scattered component of the Kuiper Belt is discussed. -

CENTRIPETAL FORCE from GRAVITY Units 14 & 8

CENTRIPETAL FORCE FROM GRAVITY Units 14 & 8 Dr. John P. Cise, Professor of Physics, Austin Com. College , 1212 Rio Grande St. Austin Tx. 78791 [email protected] & New York Times, October 20, 2016 by Nicholas St. Fleur ,Dedicated to Tyco Brahe, Danish Nobleman and astronomer ,1546 – 1601. Known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations without a telescope. Measurements done on his Danish island estate of Hven. This small island is not far from Copenhagen. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- If Planet Nine Is Out There, It Tilts Our Solar System INTRODUCTION: Purpose of this application is to Planet 9 find mass of our sun this ninth(?) planet orbits with = m provided data: T(period) = ~ 17,117 yrs. , & from Wikipedia, perigee(closeness)= 200 AU, apogee = 1200 AU, AU = astronomical unit(distance earth-sun = 1.496 11 X 10 m. R = semi major axis = (RAPOGEE + RPERIGEE)/2 Equating gravity to centripetal force: 2 2 G m MS / R = m v / R where v = 2π /T yields 2 3 2 MS = (4 π /G)( R /T ) Gravity = m v2/R GmM/R2=mv2/R Our sun, MS = ? QUESTIONS: (a) Find R in meters?, (b) Convert T = 17,117 yrs. to seconds?, (c) Find MSUN ? An artist’s rendering shows the distant view from Planet Nine back toward the sun Most people think the eight planets in our solar system orbit the sun along a straight plane, like a disc on a record player. But actually, that plane is slightly tilted, and now astronomers think they know why: The elusive Planet Nine. Earlier this year Michael Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, presented evidence that there may be a massive planet beyond Neptune orbiting the sun. -

THE ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 110, NUMBER 1 Provided Byjuly NASA Technical1995 Reports Server

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19970005091 2020-06-16T02:45:10+00:00Z View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE THE ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 110, NUMBER 1 provided byJULY NASA Technical1995 Reports Server THE ORIGIN OF PLUTO'S ORBIT: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOLAR SYSTEM BEYOND NEPTUNE RENU MALHOTRA Lunar and Planetary Institute, 3600 Bay Area Blvd., Houston,Texas 77058 Electronic mail: [email protected] Received 1995 February 22; revised 1995April 3 NASA-CR-202613 ABSTI_,ACT The origin of the highly eccentric, inclined, and resonance-locked orbit of Pluto has long been a puzzle. A possible explanation has been proposed recently [Malhotra, 1993, Nature, 365, 819] which suggests that these extraordinary orbital properties may be a natural consequence of the formation and early dynamical evolution of the outer solar system. A resonance capture mechanism is possible during the cleating of the residual planetesimal debris and the formation of the Oort Cloud of comets by planetesimal mass loss from the vicinity of the giant planets. If this mechanism were in operation during the early history of the planetary system, the entire region between the orbit of Neptune and approximately 50 AU would have been swept by first-order mean motion resonances. Thus, resonance capture could occur not only for Pluto, but quite generally for other trans-Neptunian small bodies. Some consequences of this evolution for the present-day dynamical structure of the trans-Neptunian region are (i) most of the objects in the region beyond Neptune and up to --50 AU exist in very narrow zones located at orbital resonances with Neptune (particularly the 3:2 and the 2:1 resonances); and (ii) these resonant objects would have significantly large eccentricities. -

The Kuiper Belt As a Debris Disk Renu Malhotra

The Kuiper Belt as a Debris Disk Renu Malhotra University of Arizona a vast swarm of small bodies orbiting just beyond Neptune Art by Don Dixon (2000) 1 Dynamical classes Multi-opposition TNOs+SDOs+Centaurs: orbital distribution 3:2 5:3 2:1 Resonant KBOs • (e.g., 3:2, 2:1, 5:2) 0.4 Main Belt (40 º a º 47 AU, 0.2 • ie, between 3:2 and 2:1) 400 Scattered Disk • (a > 50 AU & 30 < q º 36 AU) 30 – Extended Scattered Disk 20 (a 50 AU & q ² 36 AU) 10 Centaurs (q < a ) • Neptune 0 30 35 40 45 50 55 a (AU) (data from MPC/05-july-2004) 2 The Hot and Cold Main Belt Multi-opposition TNOs+SDOs+Centaurs: orbital distribution 3:2 5:3 2:1 0.4 0.2 400 30 20 10 0 30 35 40 45 50 55 a (AU) (data from MPC/05-july-2004) 3 The Extended Scattered Disk Multi-opposition TNOs+SDOs+Centaurs: orbital distribution 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 400 30 20 10 0 100 200 300 400 500 a (AU) (data from MPC/05-july-2004) 4 The Edge of the Main Belt (Allen, Bernstein & Malhotra 2001, Trujillo & Brown 2001) KB Radial distribution (Trujillo & Brown, 2001). 5 Size Distribution Observed KBOs have radii • 10 º R º 1000 km 4 – Æ (Ê > 50 km) 5 ¢ 10 – main belt mass 0:01 M ⊕ – total mass (< 50AU) º 0 :03M ⊕ – 100¢ asteroid belt Size-class correlations • – “excited” KBOs contain more large objects & fewer small objects compared to the “classical” KBOs – largest CKBO is 1/60th mass of Pluto Collisional evolution models (Stern • 1995, Durda & Stern 2000) indicate that collisions are destructive for D º 100–300 km, in the present environment Bernstein et al (2004). -

Resonant and Secular Families of the Kuiper Belt

RESONANT AND SECULAR FAMILIES OF THE KUIPER BELT E. I. CHIANG and J. R. LOVERING University of California at Berkeley R. L. MILLIS, M. W. BUIE and L. H. WASSERMAN Lowell Observatory K. J. MEECH Institute for Astronomy, Hawaii Abstract. We review ongoing efforts to identify occupants of mean-motion resonances (MMRs) and collisional families in the Edgeworth–Kuiper belt. Direct integrations of trajectories of Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) reveal the 1:1 (Trojan), 5:4, 4:3, 3:2 (Plutino), 5:3, 7:4, 9:5, 2:1 (Twotino), and 5:2 MMRs to be inhabited. Apart from the Trojan, resonant KBOs typically have large orbital eccentricities and inclinations. The observed pattern of resonance occupation is consistent with resonant capture and adiabatic excitation by a migratory Neptune; however, the dynamically cold initial conditions prior to resonance sweeping that are typically assumed by migration simulations are probably inadequate. Given the dynamically hot residents of the 5:2 MMR and the substantial inclinations observed in all exterior MMRs, a fraction of the primordial belt was likely dynamically pre-heated prior to resonance sweeping. A pre-heated population may have arisen as Neptune grav- itationally scattered objects into trans-Neptunian space. The spatial distribution of Twotinos offers a unique diagnostic of Neptune’s migration history. The Neptunian Trojan population may rival the Jovian Trojan population, and the former’s existence is argued to rule out violent orbital histories for Neptune. Finally, lowest-order secular theory is applied to several hundred non-resonant KBOs with well-measured orbits to update proposals of collisional families.