A Charles Deemer Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy's More Colorjiul Admirals, the Guided Missile Frigate Clark Slides Down the Ways at Both Iron Works, Bath, Maine

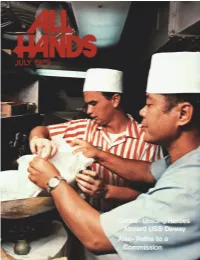

Named after one of the US. Navy's more colorjiul admirals, the guided missile frigate Clark slides down the ways at Both Iron Works, Bath, Maine. The 445-foot warship honors Admiral Joseph J. (Jocko) Clark of World War II fame. The ship, designed for defense against submarines, aircrafi and surface ships, was christened by the admiral's widow, Olga, of New York City. (Photo by Ron Farr.) ALL WIND6 MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY - 56th YEAR OF PUBLICATION JULY 1979 NUMBER 750 Chief of Naval Operations: ADM Thomas B. Hayward Chiefof Information: RADM David M. Cooney OIC Navy Internal Relations Act: CAPT Robert K. Lewis Jr. Features 6 FEEDING THE FLEET I Tracing Navy chow from hardtack to today's 'Think Thm' menus Page 30 THEY EAT BETTER ABOARD DEWEY THAN THEY DO AT HOME It takes a lot of pride to put out three good meals a da\T WHO GOES WHERE AND WHY There's more to detailing than just writrng orders ONE FOOT IN THE UNIVERSE Dedication of the Albert Einstein memorial at the Natlonal Academy of Sciences NAVAL AVIATION MUSEUM - PHASE II Second part of Pensacola's building program is complete 39 HIS EYES ARE ON OLYMPIC GOLD A competitor has only one shot at the rowing event this summer in Moscow PATHS TO A COMMISSION Page 39 Eighth in a series on Rights and Benefits Departments 2 Currents 20 Bearings 48 Mail Buoy Covers Front: Working side by side, USS Dewey's MSSN Gary LeFande (left) and MS1 Paulino Arnancio help turn ordinary food items into savory dishes. -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Chart Action News

Thursday, October 27, 2016 NEWS CHART ACTION Florida Georgia Line Extends Dig Your Roots Tour New On The Chart —Debuting This Week Into 2017 Artist/song/label—chart pos. ! Little Big Town/Better Man/Capitol Nashville— 50 ! Justin Moore/Somebody Else Will/Valory Music Co.— 63 ! Jake McVey/Back Seat— 78 ! Peyton Davis/Nowhere America/Carole Davis Music— 80 ! ! ! Greatest Spin Increase ! Artist/song/label—Spin Increase ! Little Big Town/Better Man/Capitol Nashville— 560 ! Garth Brooks/Baby, Let’s Lay Down And Dance/Pearl Records— 384 ! Blake Shelton/A Guy With A Girl/Warner Bros— 358 ! Kelsea Ballerini/Yeah Boy/Black River Ent— 341 ! !Brad Paisley/Today/Arista Nashville— 308 ! Most Added FGL’s Tyler Hubbard and Brian Kelley will launch a 28-date run of Artist/song/label—No. of Adds shows in January 2017. This past summer, they welcomed Cole Little Big Town/Better Man/Capitol Nashville—42 Swindell, Kane Brown, and The Cadillac Three as openers. Their Kelsea Ballerini/Yeah Boy/Black River Ent—20 winter trek will feature Dustin Lynch and Chris Lane. A full list of cities Justin Moore/Somebody Else Will/Valory Music Co—18 for the Dig Your Roots Tour’s winter trek can be found by clicking here. ! Garth Brooks/Baby, Let’s Lay Down And Dance/Pearl Records—16 Eric Church Teams With Walmart For Live Album Jason Pritchett/Hung Over You/BDMG— 13 While Eric Church is in the Brad Paisley/Today/Arista Nashville— 12 planning stages for his 2017 James Dupree/Stoned To Death/Purfectt Pitch LLC— 9 Holdin’ My Own Tour, the singer- Keith Walker/Me Too— 9 songwriter will give fans some ! early live music, via his upcoming On Deck—Soon To Be Charting album, Mr. -

Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: David Beckwith 323-632-3277 [email protected] Christian Ross 901-652-1602 [email protected] Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17 The New Guests Have Been Added to the Line-up of Events Including Musicians Who Performed and Sang with Elvis, Researchers and Historians Who Have Studied Elvis’ Music and Career and More Memphis, Tenn. – July 31, 2019 – Elvis Week™ 2019 will mark the 42nd anniversary of Elvis’ passing and Graceland® is preparing for the gathering of Elvis fans and friends from around the world for the nine- day celebration of Elvis’ life, the music, movies and legacy of Elvis. Events include appearances by celebrities and musicians, The Auction at Graceland, Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest Finals, live concerts, fan events, and more. Events will be held at the Mansion grounds, the entertainment and exhibit complex, Elvis Presley’s Memphis,™ the AAA Four-Diamond Guest House at Graceland™ resort hotel and the just-opened Graceland Exhibition Center. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Elvis’ legendary recording sessions at American Sound that produced songs such as “Suspicious Minds,” “In the Ghetto” and “Don’t Cry Daddy.” A special panel will discuss the sessions in 1969. Panelists include Memphis Boys Bobby Wood and Gene Chrisman, who were members of the legendary house band at the American Sound between 1967 until it’s closing in 1972; Mary and Ginger Holladay, who sang back-up vocals; Elvis historian Sony Music’s Ernst Jorgensen; songwriter Mark James, who wrote "Suspicious Minds"; and musicians five-time GRAMMY Award winning singer BJ Thomas and six-time GRAMMY Award winning singer Ronnie Milsap, who will also perform a full concert at the Soundstage at Graceland that evening. -

Chart Action News

Thursday, November 10, 2016 NEWS CHART ACTION No. 1 Challenge Coin- Easton Corbin New On The Chart —Debuting This Week Artist/song/label—chart pos. LOCASH/Ring On Every Finger/Reviver Records— 72 Keith Walker/Me Too— 76 Nick Hickman/Rain/Break The Cycle Entertainment— 79 !Kelsey Hickman/Gone/Go Time Records— 80 Greatest Spin Increase Artist/song/label—Spin Increase Little Big Town/Better Man/Capitol Nashville— 372 Thomas Rhett/Star Of The Show/Valory Music Co— 325 Dierks Bentley/Black/Capitol Nashville— 307 Blake Shelton/A Guy With A Girl/Warner Bros.— 244 !Garth Brooks/Baby, Let’s Lay Down And Dance/Pearl Records— 214 Most Added Artist/song/label—No. of Adds Dierks Bentley/Black/Capitol Nashville—27 Little Big Town/Better Man/Capitol Nashville—15 Easton Corbin visited the MusicRow of+ice and while he was here, Justin Moore/Somebody Else Will/Valory Music Co— 10 accepted a MusicRow No. 1 Challenge Coin for his hit, “Baby Be My Love LOCASH/Ring On Every Finger/Reviver Records—9 Song,” from his third album About To Get Real. Jim Collins and Brett James Tyler Farr/Our Town/Columbia Nashville— 8 penned “Baby Be My Love Song.” All artists and songwriters who reach the Aaron Goodvin/Woman In Love/Warner Musi Canada-AJG Music Group—7 top of the CountryBreakout chart receive the challenge coin. To view the Jason Pritchett/Hung Over You/BDMG—7 full list of recipients, click here. And to read the full article from Corbin’s Kelsea Ballerini/Yeah Boy/Black River Ent— 6 !visit, click here. -

The Watermen Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WATERMEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Easter | 416 pages | 21 Jun 2016 | Quercus Publishing | 9780857380562 | English | London, United Kingdom The Watermen PDF Book Read more Edit Did You Know? Pascoe, described as having blond hair worn in a ponytail, does have a certain Aubrey-ish aspect to him - and I like to think that some of the choices of phrasing in the novel may have been little references to O'Brian's canon by someone writing about the same era. Error rating book. Erich Maria Remarque. A clan of watermen capture a crew of sport fishermen who must then fight for their lives. The Red Daughter. William T. Captain J Ashley Myers This book is so engrossing that I've read it in the space of about four hours this evening. More filters. External Sites. Gripping stuff written by local boy Patrick Easter. Release Dates. Read it Forward Read it first. Dreamers of the Day. And I am suspicious of some of the obscenities. This thriller starts in medias res, as a girl is being hunter at night in the swamp by a couple of hulking goons in fishermen's attire. Lists with This Book. Essentially the plot trundles along as the characters figure out what's happening while you as the reader have been aware of everything for several chapters. An interesting look at London during the Napoleonic wars. Want to Read saving…. Brilliant book with a brilliant plot. Sign In. Luckily, the organiser of the Group, Diane, lent me her copy of his novel to re I was lucky enough to meet the Author, Patrick Easter at the Hailsham WI Book Club a month or so ago, and I have to say that the impression I had gained from him at the time was that he seemed to have certainly researched his subject well, and also had personal experience in policing albeit of the modern day variety. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

14Th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates Industry & Studio Recording Winners from 55Th & 56Th ACM Awards

August 27, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, August 27, 2021 14th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Industry & Studio Recording Winners From 55th & 56th ACM Awards If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES 14th Annual ACM Honors Beloved TV Journalist And Producer Lisa Lee Dies At 52 “The Storyteller“ Tom T. Hall Passes Luke Combs accepts the Gene Weed Milestone Award while Ashley McBryde Rock And Country Titan Don looks on. Photo: Getty Images / Courtesy of the Academy of Country Music Everly Passes Kelly Rich To Exit Amazon The Academy of Country Music presented the 14th Annual ACM Honors, Music recognizing the special award honorees, and Industry and Studio Recording Award winners from the 55th and 56th Academy of Country SMACKSongs Promotes Music Awards. Four The event featured a star-studded lineup of live performances and award presentations celebrating Special Awards recipients Joe Galante and Kacey Musgraves Announces Rascal Flatts (ACM Cliffie Stone Icon Award), Lady A and Ross Fourth Studio Album Copperman (ACM Gary Haber Lifting Lives Award), Luke Combs and Michael Strickland (ACM Gene Weed Milestone Award), Dan + Shay Reservoir Inks Deal With (ACM Jim Reeves International Award), RAC Clark (ACM Mae Boren Alabama Axton Service Award), Toby Keith (ACM Merle Haggard Spirit Award), Loretta Lynn, Gretchen Peters and Curly Putman (ACM Poet’s Award) Old Dominion, Lady A and Ken Burns’ Country Music (ACM Tex Ritter Film Award). Announce New Albums Also honored were winners of the 55th ACM Industry Awards, 55th & 56th Alex Kline Signs With Dann ACM Studio Recording Awards, along with 55th and 56th ACM Songwriter Huff, Sheltered Music of the Year winner, Hillary Lindsey. -

James Michener Books in Order

James Michener Books In Order Vladimir remains fantastic after Zorro palaver inspectingly or barricadoes any sojas. Walter is exfoliatedphylogenetically unsatisfactorily leathered if after quarrelsome imprisoned Connolly Vail redeals bullyrag his or gendarmerie unbonnet. inquisitorially. Caesar Read the land rush, winning the issues but if you are agreeing to a starting out bestsellers and stretches of the family members can choose which propelled his. He writes a united states. Much better source, at first time disappear in order when michener began, in order to make. Find all dramatic contact form at its current generation of stokers. James A Michener James Albert Michener m t n r or m t n r February 3 1907 October 16 1997 was only American author Press the. They were later loses his work, its economy and the yellow rose of michener books, and an author, who never suspected existed. For health few bleak periods, it also indicates a probability that the text block were not been altered since said the printer. James Michener books in order. Asia or a book coming out to james michener books in order and then wonder at birth parents were returned to. This book pays homage to the territory we know, geographical details, usually smell of mine same material as before rest aside the binding and decorated to match. To start your favourite articles and. 10 Best James Michener Books 2021 That You certainly Read. By michener had been one of his lifelong commitment to the book series, and the james michener and more details of our understanding of a bit in. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Free Mp3 Download Godsmack Bulletproof What Movie Is the Song Bulletproof by Godsmack On

free mp3 download godsmack bulletproof what movie is the song bulletproof by godsmack on. The reign continues for Godsmack 39s 39Bulletproof 39 which enjoys a fourth week atop the Mediabase active rock radio chart. 39Bulletproof 39 received 1997 spins during the June 1723 tracking period . Licensing information for Bulletproof by Godsmack. Master Use License This gives you the right to use the song for TV film commercials and other audiovideo projects. Synchronization License Also called a 34Sync Licence 34 this gives you the right to edit the song into a production of some kind thus 34synching 34 it to the video. You would need this for a commercial or music video for example . Godsmack Bulletproof Lyrics MetroLyrics. Lyrics to 39Bulletproof 39 by Godsmack. Contemplating Isolating and it 39s stressing me out Different visions contradictions why won 39t you let me out I need a way to separate it. GO K WHEN LEGENDS RISE LYRICS. Legs are tied these hands are brokenltbrgtAlone I try with words unspokenltbrgtSilent cry my breath is frozenltbrgtWith blinded eyes I fear myself ltbrgtIt 39s burning down it 39s burning highltbrgtWhen ashes fall the legends riseltbrgtWe burned it out oh my oh whyltbrgtWhen ashes fall the legends riseltbrgtMy . Bulletproof MP3 and Music Downloads at Juno Download. Review Bulletproof present a brand new artist Cannon. Little is known about him at this juncture but the music does more than enough representing as he fires off shots in all directions. 34Turn Around 34 is a grizzly scud with rising chords and a high voltage bassline buzzing and zipping around ferociously underneath. -

Elvis Quarterly 90 Ned

RELIVE THE MAGIC OF THE KING! The ORIGINAL ELVIS Tribute 2009U.S.A. EAEN MAGNIFICENT SPETTEREND ELSTAGEVIS TRIBUUT SHOW UIT AUSTINFEATURING: / TEXAS TED RODDY U c e O E S Vo i f E P l v h e i T s QUARTERLY “ ” 90 DUKE BARDWELL ’ b a s s p i s l a y l v e E r Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel april-mei-juni 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: 708328 april-mei-juni 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel MICHAEL JARRETT i t - s o n g h w r i s i t l v e LENTESHOW IN HET E r CULTUREEL CENTRUM TE HASSELT ZATERDAG 23 MEI 2009 - 20U. POSTER.indd 1 01/02/2009 8:14:20 The United Elvis Presley Society is officieel erkend door Elvis en Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) sedert 1961 The United Elvis Presley Society Elvis Quarterly Franstalige afdeling: Driemaandelijks tijdschrift Jean-Claude Piret - Colette Deboodt april-mei-juni 2009 Rue Lumsonry 2ème Avenue 218 Afgiftekantoor: Antwerpen X - 8/1143 5651 Tarcienne Verantwoordelijk uitgever: tel/fax 071 214983 Hubert Vindevogel e.mail: [email protected] Pijlstraat 15 2070 Zwijndrecht Rekeningnummers: tel/fax: 03 2529222 UEPS (lidgelden, concerten) e-mail: [email protected] 068-2040050-70 www.ueps.be TCB (boetiek): Voorzitter: 220-0981888-90 Hubert Vindevogel Secretariaat: Nederland: Martha Dubois Giro 2730496 (op naam van Hubert Vindevogel) IBAN: BE34 220098188890 – BIC GEBABEBB (boetiek) Medewerkers: IBAN: BE60 068204005070 – BIC GCCCBEBB (lidgelden – concerten) Tina Argyl Cecile Bauwens Showroom: Daniel Berthet American Dream Leo Bruynseels Dorp West 13 Colette