Maternal Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elsie Widdowson

MARGARET NEWMAN : ELSIE WIDDOWSON Elsie Widdowson Pioneer of Nutritional Studies Born 1906 in Wallington Surrey, attended Sydenham County Grammar School Studied Chemistry at Imperial College, London and graduated with BSc in 1928 becoming one of the first women graduates of Imperial College.carrying out postgraduate work at The Dept of Plant Physiology, developing methods for separating and measuring the fructose, sucrose and hemicellulose of fruit. She measured changes in the carbohydrates in fruit from time it appeared on tree until it ripened. 1931 she received PhD in Chemistry for her thesis on the carbohydrate content of apples. Her main interest was the biochemistry of animals and humans. And together with Professor Dodds studied the metabolism of the kidneys and she received a doctorate from the Courtauld Institute. Elsie struggled to find a long term position, Dr Dodds suggested she consider specialising in dietetics, which she did learning about the composition of meat and fish and how cooking affected them. While studying industrial cooking techniques she teamed up with Robert McCance who was a junior doctor researching chemical effects of cooking as part of his research on the treatment of diabetes. Elsie pointed out a error in his analysis of the fructose content of fruit. They became scientific partners and worked together for 60 years until McCance died in 1993. They worked on the chemical composition of the human body and on the nutritional value of different flours used to make bread. Elsie with McCance also studied the impact of infant diet on human growth. They studied the effects from deficiencies of salt and water, and produced the first tables to compare the different nutritional content of foods before and after cooking. -

Calendario De Mujeres Científicas Y Maestras

Mil Jardines Ciencia y Tecnología Calendario de Mujeres Científicas y Maestras Hipatia [Jules Maurice Gaspard (1862–1919)] Por Antonio Clemente Colino Pérez [Contacto: [email protected]] CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA Mil Jardines . - Calendario de Mujeres Científicas y Maestras - . 1 – ENERO Marie-Louise Lachapelle (Francia, 1769-1821), jefe de obstetricia en el Hôtel-Dieu de París, el hospital más antiguo de París. Publicó libros sobre la anatomía de la mujer, ginecología y obstetricia. Contraria al uso de fórceps, escribió Pratique des accouchements, y promovió los partos naturales. https://translate.google.es/translate?hl=es&sl=ca&u=https://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie-Louise_Lachapelle&prev=search Jane Haldiman Marcet (Londres, 1769-1858), divulgadora científica que escribió sobre química, enero 1 botánica, religión, economía y gramática. Publicó Conversations on Chemistry, con seudónimo masculino en 1805, pero no fue descubierta su autoría hasta 1837. https://lacienciaseacercaalcole.wordpress.com/2017/01/23/chicas-de-calendario-enero-primera-parte/ https://mujeresconciencia.com/2015/08/19/michael-faraday-y-jane-marcet-la-asimov-del-xix/ Montserrat Soliva Torrentó (Lérida, 1943-2019), doctora en ciencias químicas. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montserrat_Soliva_Torrent%C3%B3 Florence Lawrence (Canadá, 1886-1938), actriz del cine mudo apasionada por los coches, que inventó el intermitente, pero no lo consideró como propio y pasó el final de sus días sola y arruinada. https://www.motorpasion.com/espaciotoyota/el-dia-que-una-mujer-invento-el-intermitente-y-la-luz-de-freno-para-acabar-despues- arruinada Tewhida Ben Sheikh (Túnez, 1909-2010), primera mujer musulmana en convertirse en medica y llegó a plantear temas como la planificación familiar, la anticoncepción y el aborto en su época, en el norte enero 2 de Africa. -

Prenatal Corticosteroids for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality After Preterm Birth

PRENATAL CORTICOSTEROIDS FOR REDUCING MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY AFTER PRETERM BIRTH The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 15 June 2004 Edited by L A Reynolds and E M Tansey Volume 25 2005 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2005 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2005 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 0 85484 102 8 Histmed logo images courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London. All volumes are freely available online at: www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as: Reynolds L A, Tansey E M. (eds) (2005) Prenatal Corticosteroids for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality after Preterm Birth. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 25. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. CONTENTS Illustrations and credits v Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications; Acknowledgements vii E M Tansey and L A Reynolds Introduction xxi Barbara Stocking Transcript 1 Edited by L A Reynolds and E M Tansey Appendix 1 85 Letter from Professor Sir Graham (Mont) Liggins to Sir Iain Chalmers (6 April 2004) Appendix 2 89 Prenatal glucocorticoids in preterm birth: a paediatric view of the history of the original studies by Ross Howie (2 June 2004) Appendix 3 97 Premature sheep and dark horses: Wellcome Trust support for Mont Liggins’ work, 1968–76 by Tilli Tansey (25 October 2005) Appendix 4 101 Prenatal corticosteroid therapy: early Auckland publications, 1972–94 by Ross Howie (January 2005) Appendix 5 103 Protocol for the use of corticosteroids in the prevention of respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. -

Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences”

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences" Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 05 March 2021 Version 1.35 Title word cross-reference + [Cla07a]. = = [Nic13]. $19.95 [Tur18]. $25 [Oka03]. $27.95 [Har13a]. 3 [Bra11b]. $39.95 [DiM18]. $40.00 [Ayl18]. $45.00 [Ren15]. $58.99 [Tor13]. 1 [Fis15]. -dimensions [Bra11b]. -I [Ste08]. -no [Ste08]. 0 [Dea10, Oka03, Ren15, Tor13, Whi04]. 0-14-017309-9 [Whi04]. 0-19-508820-4 [Sar98]. 0-19-508821-2 [Sar98]. 0-226-20791-9 [Dea10]. 0-226-90134-3 [Oka03]. 0-262-01167-0 [Aga01]. 0-521-49544-X [Gur98]. 0-7619-5425-2 [Mur01]. 0-7619-5426-0 [Mur01]. 0-7914-1260-1 [Wil98]. 1 2 1 [Alt07, Cob15]. 17.99 [Mur01]. 1840s [BL07]. 1859-1914 [Coh17]. 1875-1944 [FM07]. 1876 [FS15]. 19.95 [Sar98]. 1920s [Erl09]. 1930s [OG14]. 1940s [Tur20]. 1950s [L¨ow12, Mor14, Qui05, Iid20]. 1960s [Hag01, Kel11b, Qui05, SD14]. 1970s [Fay12]. 1980s [Ser11, WL08, Wyl10]. 1990s [WL08, Wyl10]. 19th [Gis20]. 1The [Hag01]. 2 [Alt08b, DiM18, Hal18, Qui04, TB16]. 2-7071-3607-7 [Qui04]. 2005 [Sha14]. 2006 [Ano07a]. 2009 [Ano09a]. 2019 [Ano19a, Ano19b, Ano19i]. 2020 [Ano20a, Ano20b, Ano20c, Ano20j, Ano20k]. 20th [BP15, Gis20, Sko11]. -

Prenatal Corticosteroids for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality After Preterm Birth

PRENATAL CORTICOSTEROIDS FOR REDUCING MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY AFTER PRETERM BIRTH The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 15 June 2004 Edited by L A Reynolds and E M Tansey Volume 25 2005 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2005 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2005 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 0 85484 102 4 Histmed logo images courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London. All volumes are freely available online following the links to Publications/Wellcome Witnesses at www.ucl.ac.uk/histmed Technology Transfer in Britain:The case of monoclonal antibodies; Self and Non-Self: A history of autoimmunity; Endogenous Opiates; The Committee on Safety of Drugs • Making the Human Body Transparent: The impact of NMR and MRI; Research in General Practice; Drugs in Psychiatric Practice; The MRC Common Cold Unit • Early Heart Transplant Surgery in the UK • Haemophilia: Recent history of clinical management • Looking at the Unborn: Historical aspects of obstetric ultrasound • Post Penicillin Antibiotics: From acceptance to resistance? • Clinical Research in Britain, 1950–1980 • Intestinal Absorption • Origins of Neonatal Intensive Care in the UK • British Contributions to Medical Research and Education in Africa after the Second World War • Childhood Asthma and Beyond • Maternal Care • Population-based Research -

The Resurgence of Breastfeeding, 1975–2000

THE RESURGENCE OF BREASTFEEDING, 1975–2000 The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 24 April 2007 Edited by S M Crowther, L A Reynolds and E M Tansey Volume 35 2009 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2009 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2009 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 085484 119 6 All volumes are freely available online following the links to Publications/Wellcome Witnesses at www.ucl.ac.uk/histmed Technology Transfer in Britain: The case of monoclonal antibodies; Self and Non-Self: A history of autoimmunity; Endogenous Opiates; The Committee on Safety of Drugs • Making the Human Body Transparent: The impact of NMR and MRI; Research in General Practice; Drugs in Psychiatric Practice; The MRC Common Cold Unit • Early Heart Transplant Surgery in the UK • Haemophilia: Recent history of clinical management • Looking at the Unborn: Historical aspects of obstetric ultrasound • Post Penicillin Antibiotics: From acceptance to resistance? • Clinical Research in Britain, 1950–1980 • Intestinal Absorption • Origins of Neonatal Intensive Care in the UK • British Contributions to Medical Research and Education in Africa after the Second World War • Childhood Asthma and Beyond • Maternal Care • Population-based Research in South Wales: The MRC Pneumoconiosis Research Unit and the MRC Epidemiology Unit -

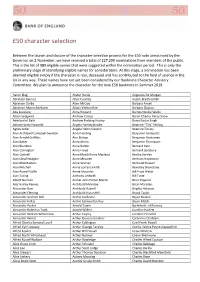

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

The History of Newborn Resuscitation, 1929 to 1970

Learning to Breathe: The History of Newborn Resuscitation, 1929 to 1970. Rachel McAdams Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Glasgow Faculty of Law, Business and Social Science (October 2008) 2 Abstract The history of newborn resuscitation in the twentieth century presented thus far in the writings of practitioner-historians describes a ‘hands-off’ attitude to newborn care prior to the 1950s. These practioner-historians tend to recount a positivist narrative with the rapid expansion of newborn care after WWII and the eventual logical uptake of endotracheal intubation and positive pressure resuscitation as the most effective method for treating asphyxia neonatorum. This thesis challenges this positivist narrative my examining the resuscitation of the newborn in Britain and America during the interwar period through to the late 1960s. It uncovers a much more complex and non-linear narrative for the development of newborn resuscitation during the twentieth century, uncovering some interesting themes which the practitioner-histories have not addressed. These themes include the interactions between neonatal and fetal physiologists and their research with clinicians and clinical practice, and the role of new groups of clinicians, the paediatricians and anaesthetists, in newborn resuscitation during this period. Many of the practitioner-histories ridicule what they deem to be ‘failed’ resuscitation techniques, seeing them as ‘deveiations’ from the eventual widespread adoption of positive pressure methods. My analysis of both the clinical and scientific debates surrounding both the use of positive pressure methods and some of these ‘failed’ techniques provides a more complex and detailed story. Two techniques in particular, intragastric oxygen and hyperbaric oxygen, provide useful case-studies to reflect on the factors which influenced the development of newborn resuscitation during the twentieth-century. -

Elsie Widdowson

Elsie Widdowson Elle est née le 21 octobre 1906 et morte le 14 juin 2000. Elle était une diététiste et nutritionniste britannique. Elle et Robert McCance, pédiatre, physiologiste, biochimiste et nutritionniste, étaient chargés de superviser l'ajout de vitamines aux aliments et le rationnement en temps de guerre en Angleterre pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Dans les années 1920 et 1930, les possibilités professionnelles pour les femmes. En dehors de l'enseignement, étaient limitées. Elle a suivi une formation de chimiste à « l'Impérial collège » à Londres et a obtenu un BSC en 1928, qu’il l’a fait devenir l'une des premières femmes diplômées du Collège. Elle a fait des travaux en physiologie végétale et a développé des méthodes pour séparer et mesurer le fructose, le glucose, le saccharose et l'hémicellulose des fruits. Elle mesurait les changements des glucides dans les fruits depuis l'arbre jusqu'à leur mûrissement. En 1931, elle obtient son doctorat en chimie grâce à sa thèse sur la teneur en glucides des pommes. Malgré le fait que depuis le début elle se soit seulement intéressé aux plantes et aux fruits, en réalité Widdowson était beaucoup plus intéressée par les animaux et les humains. Elle a fait d'autres recherches avec le professeur Charles Dodds à l'institut de l’hôpital Middlesex, sur le métabolisme des reins et a eu un doctorat de l'Institut Courtauld. Bien qu’elle ait obtenu un doctorat, elle avait encore du mal à trouver un poste. Alors le Dr Dodds a suggéré à Widdowson de se spécialiser en diététique. -

Elsie Widdowson Lecture 2006 Mining the Depths: Metabolic Insights Into Mineral Nutrition

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2007), 66, 512–521 DOI:10.1017/S0029665107005836 g The Author 2007 The Winter Meeting of the Nutrition Society, an international conference to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of Elsie Widdowson, hosted by MRC Human Nutrition Research Cambridge jointly with the Neonatal Society supported by the Royal Society of Medicine was held at Churchill College, Cambridge on 11–13 December 2006 Symposium on ‘Nutrition in early life: new horizons in a new century’ Elsie Widdowson Lecture 2006 Mining the depths: metabolic insights into mineral nutrition Ann Prentice MRC Human Nutrition Research, Elsie Widdowson Laboratory, Cambridge CB1 9NL and MRC Keneba, The Gambia 2006 marked the centenary of the birth of Dr Elsie Widdowson, a pioneer of nutrition science. One of the hallmarks of Elsie Widdowson’s research was an integrative approach that re- cognised the importance of investigating the mechanisms underpinning a public health or clinical issue at all levels, looking into the physiology, comparative biology, intermediate metabolism and basic science. The theme of the present lecture, given in celebration of the work of Dr Widdowson, is mineral nutrition, with a particular focus on Ca, P and vitamin D. The contributions of Dr Widdowson to the early understanding of mineral nutrition are reviewed and the latest scientific findings in this rapidly-expanding field of research are presented. Calcium: Elsie Widdowson: Mineral metabolism: Phosphorus: Vitamin D Dr Elsie Widdowson was a far-sighted pioneer of nutrition Stratum 1: public health science who maintained enthusiasm for her subject The journey starts where Elsie would have expected, i.e. -

Obituaries 2000S

OBITUARIES 61 OBITUARIES Dr Ron Snaith, 1947-2000 The whole of the chemistry community, as well as Ron' s many friends and colleagues in his other spheres of life, were deeply shocked and saddened by his sudden death on New Year's Day. Ron had been diagnosed with a serious illness some little while before Christmas, and was fighting it with his normal resolve, humour and true 'Yorkshire grit', when he collapsed at home and died in Addenbrookes Hospital a few hours later. Ron leaves his wife, Jane, and two children, Tom and Katie. Jane works in the Department of Genetics, in Cambridge. Tom is in his final year at the University of Durham, reading Chemistry, and Katie is in her second year at the University of Newcastle, Northumbria. The thoughts of all who knew Ron and his family are with them at this very sad time. Ron was born in Kingston-upon-Hull in August 1947, and was fiercely proud of his Yorkshire heritage. Ron studied Chemistry at the University of Durham between 1965-1971, graduating with a 1st Class Honours Degree in 1968, and then going on to read for a PhD, in Pure Science, under the supervision of Professor Ken Wade, FRS. His PhD was in the general area of Main Group Co-ordination Chemistry with particular reference to the investigation of the nature of covalent bonding between organo-nitrogen ligands and metals and semi-metals. Once his thesis was completed Ron then embarked on a career in school teaching. He took a PGCE in the Department of Education at Durham, and then taught at the Durham Johnston Comprehensive School between 1972 and 1979, where he soon became Head of Chemistry. -

Origins of Neonatal Intensive Care in the Uk

Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine ORIGINS OF NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE IN THE UK A Witness Seminar held at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, on 27 April 1999 Witness Seminar Transcript edited by D A Christie and E M Tansey Introduction by Professor Peter Dunn Volume 9 – April 2001 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2001 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2001 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 085484 076 2 All volumes are freely available online at: www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as: Christie D A, Tansey E M. (eds) (2001) Origins of Neonatal Intensive Care. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 9. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. Key Front cover photographs, L to R from the top: Dr Herbert Barrie Professor David Edwards, Dr Jean Smellie, Professor Osmund Reynolds Professor Sir David Hull, Sir Christopher Booth Professor Malcolm Levene, Dr Lilly Dubowitz Professor Osmund Reynolds, Professor Robert Boyd (chair) Dr Rodney Rivers, Dr Pamela Davies (1924–2009) Professor Harold Gamsu (1931–2004), Professor Jonathan Wigglesworth Professor John Davis, Professor David Harvey Back cover photographs, L to R from the top: Dr Lilly Dubowitz, Professor David Delpy Professor Maureen Young, Dr Pamela Davies (1924–2009) Professor Neil McIntosh, Professor Denys Fairweather, Professor Sir David Hull Dr Beryl Corner (1910–2007), Professor Eva Alberman Professor Victor Dubowitz, Professor Malcolm Levene Professor Tom Oppé (1925–2007) CONTENTS Introduction Professor Peter Dunn i Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications iv Transcript 1 Plates Figure 1 Neonatal mortality rate/1000 live births under 2000g.