43 Laundering Required Once a Child Is Fed. the Chair's Juxtaposition Makes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8

Oral history interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Jere Osgood on September 19 and October 8, 2001. The interview took place in Wilton, New Hampshire, and was conducted by Donna Gold for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Jere Osgood and Donna Gold have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose. Interview MS. DONNA GOLD: This is Donna Gold interviewing Jere Osgood at his home in Wilton, New Hampshire, on September 19, 2001, tape one, side one. So just tell me, you were born in Staten Island. MR. JERE OSGOOD: Staten Island, New York. MS. GOLD: And the date? MR. OSGOOD: February 7, 1936. MS. GOLD: And you were raised in Staten Island, right. MR. OSGOOD: Yeah. MS. GOLD: I was wondering whether you felt that you had the -- well, did you go into Manhattan frequently? MR. -

Wood Threads 1977, When a Man's Fancy Tumsto Fancv

Spring $2.50 Wood Threads 1977, When a man's fancy tumsto fancv. There comes a time in every Not to mention more than 170 man's life when he outgrows the bits and cutters to pick from. Or a basic power tools. When his imagi $49.99* toter kit complete with the nation calls for more. 4600 router, wrenches, edge guide, That's the perfect time for a the three bits you'll probably use the router. One of the few power tools most, and a carrying case to hold around with hardly any limitation everything. but your imagination. All in all, it's one whale of a bar Meaning you can make flutes, gain. Especially when you consider beads, reeds, rounded comers, the one feature you can't get or almost any other finishing touch anywhere else. under the sun. Plus a lot of really Rockwell engineering. practical things, like dovetails for The kind that only comes with drawers, dadoes for shelves, rabbets half a century of indus for joints, etc., etc. trial experience and on What's more, it's all pos the-job performance. for just $39.99; the pri It goes into every of a Rockwell 4600 portable and Ij2-hp Router. For some stationary tool very good reasons. aD�.. ;_ we make. Super high speed It's why (28,000 rpm), to cut fast they're all and smooth. Microm made tough, eter depth con accurate and trol to powerful. ' adjust when you're ments ready toSo let your imagi easy. Non nation go, they'll make mamng the going good. -

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

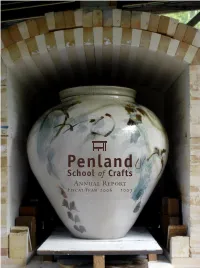

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner. -

Oral History Interview with Jere Osgood

Oral history interview with Jere Osgood Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ..................................................................................................... -

Fiscal Year 2011 Annual Report (PDF)

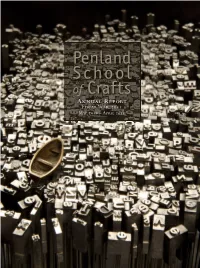

Penland School of Cra fts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2011 May – April Penland School of Crafts Penland School of Crafts is a national center for craft education located in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Penland’s focus on excel - lence, its long history, and its inspiring retreat setting have made it a model of experiential education. The school offers workshops in books and paper, clay, drawing and painting, glass, iron, metals, photography, printmaking and letterpress, textiles, wood, and other media. Penland sponsors artist residencies, a gallery and visitors center, and community education programs. Penland School of Crafts is a nonprofit, tax-exempt institution. Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland is committed to providing educational programs in a total-immersion environment that nurtures individual creativity. Penland’s programs embrace traditional and contemporary approaches that respect materials and techniques while encouraging conceptual explo - ration and aesthetic innovation. Cover Information Front cover: Adrift (detail), recycled letterpress type, wire, fabricated steel, cast bronze; this piece, by core fellow Jessica Heikes, was part of The Core Show 2010 at the Penland Gallery. To see more of Jessica’s work, visit jessicaheikes.com. Back cover: Student Eli Corbin working on a monotype in the print studio. Inside front cover: The Penland auction tent during Friday night of the Annual Benefit Auction. Inside back cover: Student Ben Grant using a lathe in the wood studio. Annual Report Credits Editor: Robin Dreyer; design: Leslie Noell; writing: Robin Dreyer, Jean McLaughlin, Wes Stitt; assistance: Kate Boyd, Mike Davis, Stephanie Guinan, Tammy Hitchcock, Polly Lórien, Nancy Kerr, Susan McDaniel, Jean McLaughlin, Jennifer Sword, Wes Stitt; photographs: Robin Dreyer, except where noted. -

James Gros See Page 2

era Publi calton of the American Crafts Council James Gros See page 2 Second Class Postage Paid at New York, NY and at Additional Mailing Office . ... - ".-.- . _. _._.- ._-_._--_._._----_._-------- CRAFT WORLD of Craft Horizons ACC NEWS Vol. XXXVIII No.4 Rose Slivka, Safari Off Editor-in-Chief Patricia Dandignac , OPEN to Africa Managing Editor Michael Lauretano, DOOR Fertility dolls and ceremonial Art Director Samuel Scherr masks, metalsmithing and pot Edith Dugmore, tery-these are some highlights Assistant Editor As of the April issue, you may of "The Art and Tradition of Michael McTwigan, have noticed that I revised the Editorial Assistant West Africa," a three-week tour heading of this column from of Senegal, Ghana, Togo, and Ni Isa bella Brandt, " Open Windows" to " Open Editorial Assistant geria (August 2-27, 1978, and Door," since I felt strongly that Anita Chmiel, January 7-31,1979). Sponsored Advertising Department the ncw and proper direction of by ACC and Art Safari, Inc., the the American Crafts Council tour is led by Art Safari codirec Editorial Board should invite an easy access to Junius Bird tor James Gross and fiber artist Jean Delius Arline Fi sc h the flow of information and ideas, Eleanor Dickinson. For the Au Persis Grayson not only within the U.S. but also gust tour contact, posthaste: 1924-1978 Robert Beverly Hale abroad. An open door is an invi Steven Adler, 800-223-0694, toll Lee Hall tation to exchange and growth. frce; or write ACC/ Art Safari. Pol ly Lada-Mocarski Another equally significant Jean Delius, jcweler and associate Harvey Littleton change is this month's CRAFT professor at New York State Col Ben Ra eburn HORIZONS with its section of lege at Oswego, died suddenly Ed Rossbach CRAFT WORLD. -

Annual Report

Annual Report / Fiscal Year 2014 / May 2013 – April 2014 Penland School of Crafts Front cover: The Barns complex houses the studios and Penland School of Crafts is an international center for craft some of the living spaces of Penland’s resident artists. This education dedicated to helping people live creative lives. photograph shows the end of one of the buildings —which Located in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, the was a dairy barn in a former life—looking into the studios of school offers workshops in books and paper, clay, drawing wood sculptor Tom Shields and weaver Robin Johnston. The and painting, glass, iron, metals, photography, printmaking year 2013 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of and letterpress, textiles, wood, and other media. Penland the resident artist program. also offers artist residencies, a gallery and visitors center, and community education programs. Penland’s focus on Back cover: Firing the wood kiln late at night. excellence, its long history, and its inspiring retreat setting have made it a model of experiential education. Penland School of Crafts is a nonprofit, tax-exempt institution. Annual Report Credits Editor: Robin Dreyer; design: Eleanor Annand; writing: Penland’s Mission Elaine Bleakney, Robin Dreyer, Jean McLaughlin; assis- The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support indi- tance: Elaine Bleakney, Marie Fornaro, Joan Glynn, Tammy vidual and artistic growth through craft. Hitchcock, Polly Lórien, Nancy Kerr, Susan McDaniel, Jean McLaughlin; photographs: Robin Dreyer, except where The Penland Vision noted. Penland is committed to providing educational programs in a total-immersion environment that nurtures individual creativity. -

Modern Furniture 5

Antikvariat ANTIQUA Kommendörsgatan 22 S-114 41 Stockholm Sweden Telefon & fax Telephone & fax 08 - 10 09 96 46 - 8 - 10 09 96 Öppettider Open hours Mändag – fredag Monday – Friday 13.00 –18.00 13.00–18.00 [email protected] www. antiqua.se VAT reg. no. SE 451124051901 Postgiro: 4 65 44 - 3 Bankgiro: 420 - 8500 The measures of books are given in cm Prices are net in Swedish Kronor Shipping charges are extra Antiqua 17 20th Century Furniture Summer 2010 Catalogued by Johan Dahlberg This catalogue presents publications on furniture from Art Nouveau to Postmodernism. Several of the books – and most of the trade catalogues – derive from the library and collection of Lena Larsson (1919-2000), the important protagonist of modern Swedish furniture and interior design. In an introduction to the catalogue, the design historian and critic Monica Boman gives her personal view on Lena Larsson’s life and career. Modern Furniture 5 Trade Catalogues and Monographs on Furniture Companies 40 NK and Triva Furniture * 60 Svenskt Tenn and Josef Frank * 68 Artek and Alvar Aalto * 73 Light Fixtures 76 Radio and TV Sets * 87 Lena Larsson * 88 Books on Individual Designers and Craftsmen 92 Books on Modern Design including but not restricted to Furniture 116 * arranged in chronological order 1 Lena Larsson – pioneer, rebel and romantic Lena Larsson – who was she, young people of today will ask. Was she the one who wanted to ”wear and tear and throw away”? It is so unfair, that this slogan – often misunderstood – is the remaining memory of one of the most influential interior designers of the 20th century, that her versatile and humanistic message and her intrepid, creative personality have been confined to a mere cliché! Lena Larsson (1919-2000) was an interior decorator and furniture designer, a teacher at the Konstfack National College of Art and Design, a popular educator, an exhibition architect and glass designer, a debater and well-known radio personality, a jazz enthusiast. -

Furniture That Winks: Wit and Conversation In

Furniture that Winks: Wit and Conversation in Postmodern Studio Furniture, 1979-1989 Julia Elizabeth T. Hood Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2011 This work was supported by a Craft Research Fund grant from The Center for Craft, Creativity and Design, a center of UNC Asheville. © 2011 Julia Elizabeth T. Hood All Rights Reserved Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Rejecting Modernism in Craft Furniture 13 Chapter 2: New Purpose for Furniture: Communicating Ideas 40 Chapter 3: A Return to History with Irony: Historicism in Craft Furniture 55 Chapter 4: What is Real?: Perception and Reality, Simulacra and Illusion 72 Conclusion 89 Notes 93 Selected Bibliography 119 Illustrations 123 i List of Illustrations* Figure 1. Garry Knox Bennet, Nail Cabinet, 1979. ....................................................... 123 Figure 2. Nail Cabinet door frame illustration. .............................................................. 123 Figure 3. Trade illustration of a Katana bull-nose router bit.......................................... 123 Figure 4. James Krenov, Jewelry Box, 1969. ............................................................... 123 Figure 5. Detail of Figure 4. .......................................................................................... 123 Figure 6. Tommy Simpson, Man -

Oral History Interview with Herta Loeser, 1989 June 6-15

Oral history interview with Herta Loeser, 1989 June 6-15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Herta Loeser on June 6, 1989. The interview took place in Cambridge, MA, and was conducted by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview RICHARD BROWN: I thought we'd just start out maybe you could talk a bit about childhood, what family you were from, about what your interests were and then we'll steer it eventually towards your great accomplishment in the crafts here in Boston. HERTA LOESER: Alright. I was born in Berlin and had to leave, my family had to leave when Hitler came to power. My father was both a photographer, it was a hobby for him - photography - but he also worked in AGFA photo firm. He had very good taste and we had in Berlin in one of the big department stores a department for ethnic art and folk art. He would go there and bring presents to us. So he had a very good eye and I think probably whatever I have of that I have inherited from him. RICHARD BROWN: Were there brothers and sisters? HERTA LOESER: Yes, I have one brother. I finished high school but not as far as one can go because I had to leave and I was the first to go to England. -

NEW HANDMADE FURNITURE Celebrates the Art, Today the Making of Handmade Furniture Is a Cul Spiri T and Vitality of Contemporary Furniture Making Tural Phenomenon

OUT OF PRINT DO NOT REMOVE NEW HAN FURNITU American Furniture Makersl Working in Hardwood ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The success of an exhibition with the scope of NEW HANDMADE n :RNITURE always depends on the NEW dedication and assistance of many people. We wish to extend our thanks to the small but energetic Museum Staff and especially to our two HANDMADE museum interns, Wendy R. Berman and Harriet Joffey. Ms. Berman has for six months been involved with every aspect of the exhibition. Har FURNITURE: riet Joffey, a graduate intern, has been responsible American Furniture Makers for biographical research. Working in Hardwood Appreciation is due the artists who have enthusi astically supported the Museum by lending their May 3-July 15,1979 New York, NY. work. For financial aid we are indebted to the Followed by a national tour National Endowment for the Arts and to the Hard wood Institute for matching funds. For general American Craft Museum overhead expenses we have been awarded a grant (formerly the Museum of by the New York State Council on the Arts for Contemporary Crafts of the which we are also very thankful. American Crafts Council) 44 West 53rd Street P.].S. New York, N.Y. 10019 Exhibition made possible by a grant from the National Endow ment for the Arts, a Federal Agency, with matching funds h-om the Hardwood Institute, A Division of the National Hard wood Lumber Association. STATEMENT NEW HANDMADE FURNITURE celebrates the art, Today the making of handmade furniture is a cul spiri t and vitality of contemporary furniture making tural phenomenon. -

Relief Carving November 1978, No

1 1 1 1 Relief Carving November 1978, No. 13 $2.50 NEW FROM mE TAUNTON PRESS... An invaluable, practical and new reference Fine · source Fine Woodworking Techniques 'leetJd1tg � Fine Woodworking TECHNIQUES, a O pages etb new book from the Taunton Press, re S. prints 50 comprehensive articles from 1 OS � flfle serlOisSoeS j!,or� �' $oad",ot the first seven issues of Fine Wood of working magazine. This volume is a timeless and invaluable reference se"etl source fo r the serious woodworker's library, containing info rmation rarely fo und in standard woodworking books. The articles present a diverse array of techniques used in the workshops of 34 expert craftsmen. 394 photographs and 180 fine drawings, as well as a compre hensive index, add to the clarity of the presentations in this 192-page volume. You'll find this book highly info rm ative fo r both current and fu ture pro jects involving cabinetmaking, carving, marquetry and turning. The book covers such topics as wood technology, 9 x 12 inches guitar joinery, bowl turning, making a 192 pages, hardcover Danish-style workbench and much, $14.00 postpaid. much more. AnWorkingMake Introduction a Chair Green from Woodto a Tree: FineBiennial Woodworking Design Book by John D. Alexander, Jr. This book details the simplicity If you love fine woodworking, of a chair held together by joints you'll treasure this superb collec that take advantage of the shrink tion of the best designs in wood ing action of drying wood. Alex by present-day craftsmen. The ander takes you step by step from 600 photographs are the pick of 9 x 9 inches felling and splitting a tree, hand 8000 sent to the editors of Fine 128 pages, softcover Woodworking , and show the in $8.