THE IMAGES of ORPHEUS and NARCISSUS Ble Power; Opposition to Such Defamation Easily Succumbs Symbols Have Been Accepted, and Their Meaning Is Usually to Ridicule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction

wendy brown Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction Feminism is a revolt against decaying capitalism. —Marcuse There is a quaintness to Herbert Marcuse’s manifesto on behalf of “feminist socialism,” here reprinted for the first time since its appearance thirty years ago in Women’s Studies. It is not only an open- hearted and hopeful little effort at theoretically codifying the expansive revolutionary promise of the second wave of the Women’s Movement, a promise that would soon be dashed from within and without. Marcuse’s political and philosophical assumptions were also vulnerable to emerg- ing postfoundational critiques of the humanist subject, progressive his- toriography, and their entailments: essentialized identities, totalizing identities, undeconstructed binary oppositions, faith in emancipation, and revolution. Openhearted, hopeful, vulnerable, imaginative, revolution- ary: precisely the qualities Marcuse thought feminism brought to the unyielding and ultimately unemancipatory rationality of a masculinist radical politics, on the one hand, and a dreamless liberal egalitarianism, on the other. This unemancipatory rationality was the terrain that the Frankfurt School worked from every direction, as it upturned the myth of Volume 17, Number 1 doi 10.1215/10407391-2005-001 © 2006 by Brown University and d i f f e r e n c e s : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/differences/article-pdf/17/1/1/405311/diff17-01_02BrownFpp.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School Enlightenment reason, integrated psychoanalysis into political philosophy, pressed Nietzsche and Weber into Marx, attacked positivism as an ideology of capitalism, theorized the revolutionary potential of high art, plumbed the authoritarian ethos and structure of the nuclear family, mapped cultural and social effects of capital, thought and rethought dialectical materialism, and took philosophies of aesthetics, reason, and history to places they had never gone before. -

The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2012 The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Joseph Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Joseph, "The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 125. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2011 By Joseph Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT Joseph Weiss Title: The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Critical Theory demands that its forms of critique express resistance to the socially necessary illusions of a given historical period. Yet theorists have seldom discussed just how much it is the case that, for Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. -

A Paper to Be Presented at the 6Th European CHEIRON Meeting in Brighton^England, 2-6 September 1987. Research Was Funded

Propriety of the Erich Fromm Document Center. For personal use only. Citation or publication of material prohibited without express written permission of the copyright holder. Eigentum des Erich Fromm Dokumentationszentrums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. Veröffentlichungen – auch von Teilen – bedürfen der schriftlichen Erlaubnis des Rechteinhabers. "INSTINCTS" AND THE "FORCES OF PRODUCTION": The Freud-Marx Debates in Eastern and Central Europe* Dr. Ferenc Eros Institute of Psychology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest In his essay "Psychology and Art Today", the British-American poet Wystan Hugh Auden writes: Both Freud and Marx start from the failures of civiliza tion, one from the poof, one from the ill. Both see human behavior determined, not consciously, but by instinctive needs, hunger and love. Both desire a world where rational choice and self-determination are possible. The difference between them is the inev itable difference between the man who studies crowds in the street, and the man who sees the patient... in the consulting room- Marx sees the direction of the relations between the outer and inner world from without inwards. Freud vice-versa.... The socialist accuses the psychologist of caving in to the status quo, trying to adapt the neurotic to the system, thus depriving him of a potential revolutionary; the psychologist retorts that the socialist is trying to lift himself by his own boot tags, that he fails to understand himself or the fact that lust for money is only one form of the lust for power; and so that after he has won his power by revolution he will recreate the same conditions. -

Critical Theory of Herbert Marcuse: an Inquiry Into the Possibility of Human Happiness

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness Michael W. Dahlem The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahlem, Michael W., "Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5620. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5620 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s, Any further reprinting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library U n iv e rs ity o f Montana Date :_____1. 9 g jS.__ THE CRITICAL THEORY OF HERBERT MARCUSE: AN INQUIRY INTO THE POSSIBILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS By Michael W. Dahlem B.A. Iowa State University, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Date UMI Number: EP41084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Historiography and Remembrance: on Walter Benjamin's Concept Of

religions Essay Historiography and Remembrance: On Walter Benjamin’s Concept of Eingedenken Charlotte Odilia Bohn Institute for Art Theory and Cultural Studies, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, 1010 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] Received: 15 November 2018; Accepted: 5 January 2019; Published: 10 January 2019 Abstract: Engaging with Walter Benjamin’s concept of Eingedenken (remembrance), this article explores the pivotal role that remembrance plays in his attempt to develop a radically new vision of history, temporality, and human agency. Building on his essay “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire” and on his last written text, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, it will trace how memory and historiography are brought together in a curious fusion of materialist and messianic thinking. Emerging from a critique of modernity and its ideology of progress that is cast as crisis—the practice of remembrance promises a ‘way out’. Many of Benjamin’s secular Marxist critics such as Max Horkheimer and Rolf Tiedemann, however, denied the political significance of Eingedenken—dismissing it as theological or banishing it to the realm of aesthetics. Rejecting this critique, I suggest that the radical ethical aspects of Eingedenken can be grasped only once the theological dimension is embraced in its own right and that it is in precisely this blend of materialist and messianic thought that revolutionary hope may be found. Keywords: Benjamin; Baudelaire; modernity; progress and catastrophe; materialism and mysticism; remembrance and historiography Only our momentary and accidental knowledge makes something rounded and changeless of the past. The smallest modification of that knowledge, such as any accident may occasion, sheds new light upon the “unchangeable” past, and suddenly, in that new light, everything acquires a different meaning and actually becomes different. -

MYTHS Echo and Narcissus Greco/Roman the Greeks

MYTHS Echo and Narcissus Greco/Roman The Greeks (and Romans) were among the early monogamous societies. The men, however, seemed to revel in stories of Zeus’ (Jupiter’s) adulterous escapades with goddesses as well as humans, and enjoyed tales of the jealousies of his wife, Hera (Juno), the goddess of marriage and the family. For the full introduction to this story and for other stories, see The Allyn & Bacon Anthology of Traditional Literature edited by Judith V. Lechner. Allyn & Bacon/Longman, 2003. From: Outline of Mythology: The Age of Fable, The Age of Chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne by Thomas Bulfinch. New York: Review of Reviews Company, 1913. pp. 101-103. Echo was a beautiful nymph, fond of the woods and hills, where she devoted herself to woodland sports. She was a favorite of Diana, and attended her in the chase. But Echo had one failing: she was fond of talking, and whether in chat or argument, would have the last word. One day Juno was seeking her husband, who, she had reason to fear, was amusing himself among the nymphs. Echo by her talk contrived to detain the goddess till the nymphs made their escape. When Juno discovered it, she passed sentence upon Echo in these words: “You shall forfeit the use of that tongue with which you have cheated me, except for the one purpose you are so fond of—reply. You shall still have the last word, but no power to speak the first.” This nymph saw Narcissus, a beautiful youth, as he pursued the chase upon the mountains. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

Dorian Gray Syndrome

Pleskovo Comprehensive Orthodox Christian Boarding School Dorian Gray Syndrome Modern society’s cognitive disease: origin, features and therapy. Author Daniil Igorevich Chugaev a senior student Supervisor Irina Vladimirovna Nickishina an English teacher 2012 Contents Prologue Oscar Wilde’s novel «The Picture of Dorian Gray»: • author’s short biography; • summary of the novel; • theme analysis. Pages 3 through 6 Keynote Dorian Gray Syndrome: • myth about Narcissus as a representation of ancient society; • becoming a trend of modern society; • origin and features; • ways of treatment. Pages 7 through 9 Conclusion Page 10 Credits Page 11 2 Prologue Oscar Wilde’s biography Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. Wilde's parents were successful Dublin intellectuals. Their son became fluent in French and German early in life. At university Wilde read Greats; he proved himself to be an outstanding classicist, first at Dublin, then at Oxford. He became known for his involvement in the rising philosophy of aestheticism, led by two of his tutors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin. He also profoundly explored Roman Catholicism, to which he would later convert on his deathbed. After university, Wilde moved to London into fashionable cultural and social circles. As a spokesman for aestheticism, he tried his hand at various literary activities: he published a book of poems, lectured in the United States of America and Canada on the new "English Renaissance in Art", and then returned to London where he worked prolifically as a journalist. -

This Body, This Civilization, This Repression: an Inquiry Into Freud and Marcuse

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2008 This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse Jeff Renaud University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Renaud, Jeff, "This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8272. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8272 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THIS BODY, THIS CIVILIZATION, THIS REPRESSION: AN INQUIRY INTO FREUD AND MARCUSE by JeffRenaud A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements -

Greek Mythology and Medical and Psychiatric Terminology

HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRY Greek mythology and medical and psychiatric terminology Loukas Athanasiadis A great number of terms in modern psychiatry, Narcissus gave his name to narcissism (ex medicine and related disciplines originate from treme self-love based on an idealised self-image). the Greek, including pathology, schizophrenia, He was a young man extremely proud of his ophthalmology, gynaecology, anatomy, pharma beauty and indifferent to the emotions of those cology, biology, hepatology, homeopathy, allo who fell in love with him. A goddess cursed him pathy and many others. There are also many to feel what it is to love and get nothing in return. terms that originate from figures from ancient He subsequently fell in love with his own image Greek mythology (or the Greek words related to when he saw his reflection in the water of a those figures) and I think that it might be fountain, and believed that this image belonged interesting to take a look at some of them. to a spirit. Every time he tried to embrace the Psyche means 'soul' in Greek and she gave her image it disappeared and appeared without names to terms like psychiatry (medicine of the saying a word. At the end the desperate soul), psychology, etc. Psyche was a mortal girl Narcissus died and was turned into a flower that with whom Eros ('love', he gave his name to still bears his name. erotomania, etc.) fell in love. Eros's mother Echo was a very attractive young nymph who Aphrodite had forbidden him to see mortal girls. always wanted to have the last word. -

The Changes of Dorian's Personality to Be Narcissistic Caused by His

The Changes of Dorian’s Personality to be Narcissistic Caused by His Environment Reflected in Oscar Wilde’s Novel The Picture of Dorian Gray SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE BY IRMA OEMAYA NIM 0811110048 STUDY PROGRAM OF ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITAS BRAWIJAYA MALANG 2013 This is to certify that the Sarjana thesis of Irma Oemaya has been approved by the Board of Supervisors. Malang, 1 Agustus 2013 Supervisor Juliati, M.Hum. NIP. Malang, 21 June 2013 Co-supervisor Fredy Nugroho S, M.Hum The Changes of Dorian’s Personality to be Narcissistic Caused by His Environment Reflected in Oscar Wilde’s Novel The Picture of Dorian Gray Irma Oemaya Study Program of English, Faculty of Culture Studies, Universitas Brawijaya Abstract God creates human with the biological aspect as the foundation that build someone from the body, personality, character, etc, and biological is not the only factor that build some one’s character. There are some key factors, which provoke particular changes in human character, and these aspects can be divided into two groups, internal and external. Everyone has different personality and character, and they also have bad side and good side inside them, which is the most strongest side will be seen clearly as they wants. The Picture of Dorian Gray is a novel with uncommon theme or supernatural thing. Yet the real theme which is going to be analyzed deal with the change Dorian’s character a handsome young man from innocent nature into an evily selfish person. Dorian Gray was a pure man until his meeting with Lord Henry brought him to realize that beauty is everything. -

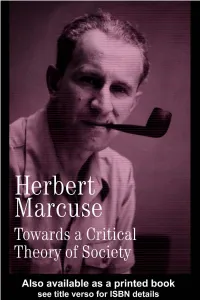

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical