Social Science in Perspective EDITORIAL BOARD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Higher Secondary: SET

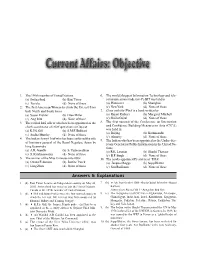

RRB PSC Higher Secondary: SET 1. The 190th member of United Nations 6. The world’s biggest Information Technology and tele- (a) Switzerland (b) East Timor communications trade fair-Ce BIT was held in (c) Tuvalu (d) None of these (a) Hannover (b) Shanghai 2. The first American Woman to climb the Everest from (c) New York (d) None of these both North and South faces 7. Gone with the Wind is a book written by (a) Susan Ershler (b) Ellen Miller (a) Rajani Kothari (b) Margaret Mitchell (c) Ang Rita (d) None of these (c) Sheila Gujral (d) None of these 3. The retired IAS officer who has been appointed as the 8. The first summit of the Conference on Interaction chief co-ordinator of relief operations in Gujarat and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) (a) K.P.S. Gill (b) S.M.F. Bokhari was held in (a) Beijing (b) Kathmandu (c) Sudha Murthy (d) None of these (c) Almatty (d) None of these 4. The Indian Army Chief who has been conferred the title 9. The Indian who has been appointed as the Under-Sec- of honorary general of the Royal Nepalese Army by retary General for Public Information in the United Na- king Gyanendra tions. (a) A.R. Gandhi (b) S. Padmanabhan (a) R.K. Laxman (b) Shashi Tharoor (c) S. Krishnaswamy (d) None of these (c) B.P. Singh (d) None of these 5. The winner of the Miss Universe title 2002 10. The newly appointed President of ‘FIFA’ (a) Oxana Fedorova (b) Justine Pasek (a) Jacques Rogge (b) Sepp Blatter (c) Ling Zhou (d) None of these (c) Sen Ruffianne (d) None of these Answers & Explanations 1. -

Building Moderate Muslim Networks

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Building Moderate Muslim Networks Angel Rabasa Cheryl Benard Lowell H. Schwartz Peter Sickle Sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation CENTER FOR MIDDLE EAST PUBLIC POLICY The research described in this report was sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation and was conducted under the auspices of the RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

KERALA KARSHAKAN E-Journal JULY 2016.Pdf

1 KERALA KARSHAKAN e-journal July 2016 2 EDITORIAL FARM INFORMATION BUREAU MEMBERS, ADVISORY COMMITTEE RICE IS LIFE CHAIRMAN Agricultural Production Commissioner MEMBERS Raju Narayana Swamy IAS or more than half of humanity, rice is life. It is the grain that Secretary (Agriculture) has shaped the cultures, diets and economies of billions of Ashok Kumar Thekkan people in Asia. Life without rice is simply unthinkable. Rice Director (Agriculture) Mini Antony IAS is the staple-food for even half of the world’s population. It Director (I&PRD) Fprovides 27% of dietary energy supply and 20% of dietary protein Dr. N.N. Sasi intake in the developing world. Director (Animal Husbandry) Coming to Kerala, rice is the staple-food of Keralites and Georgekutty Jecob Director (Dairy Department) traditionally the cultivation of rice has occupied pride of place in the R.C. Gopal agrarian economy of the state. The lush green of paddy fields is one Station Director All India Radio of the most captivating features of features of Kerala’s landscape. Director The area under paddy cultivation increased substantially during the Doordarshan, Thiruvananthapuram first fifteen years after the state’s formation but now a reversal of C. Radhakrishnan Chamravattom, Tirur, Malappuram this trend is seen. There is steady decline in the area and production Prof. Abraham P. Mathew of paddy in Kerala. Marthoma College, Chungathara PO, Malappuram Considering the fact Kerala can’t lose its rice fields the elected M. Ramachandran Government of Kerala is watchful against conservation of paddy Lakshmivaram, Sankaran Para Lane, fields. Agriculture Minister Shri. V.S. Sunilkumar made clear that Mudavanmukal, Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram the government would not allow reclaiming an inch of agricultural A. -

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

“Coming Out” Or “Staying in the Closet”– Deconversion Narratives of Muslim Apostates in Jordan

MARBURG JOURNAL OF RELIGION, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2016) 1 “Coming Out” or “Staying in the Closet”– Deconversion Narratives of Muslim Apostates in Jordan Katarzyna Sidło Abstract This article describes a pilot study conducted between 22.03.2013 and 22.05.2013 among deconverts from Islam in Jordan. Due to the religious and cultural taboo surrounding apostasy, those who left Islam are notoriously difficult to access in a systematic way and constitute what is known in social research as a ‘hidden’ or ‘hard-to-reach’ population. Consequently, the non-probability sampling methods, namely an online survey, were used to recruit participants to the study. The objective of this research was threefold: (a) exploring the community of apostates from Islam in Jordan, (b) understanding the rationale behind decision to disaffiliate from Islam, and (c) analysing their narratives of deconversion. In addition, this paper examines the changes that occurred in respondents’ lives as a result of their apostasy and the degree of secrecy about their decision. Background The problem of apostasy from Islam is a complex and controversial one. The Quran itself does not explicitly name death as a prescribed penalty for abandoning Islam. The commonly agreed interpretation of the few verses (Arabic – ayats) that mention apostasy is to the effect that Allah will inflict punishment on apostates in the afterlife (Quran, 2:17, 3:87, 9:74, 18:291; usually invoked in this context is ayat from surah Al-Baqara (2:256) “There is no compulsion in religion”2). In the Sunna, on the other hand, we can find a number of hadiths (e.g. -

Sona Grigoryan Supervisor: Aziz Al-Azmeh

Doctoral Dissertation POETICS OF AMBIVALENCE IN AL-MA‘ARRĪ’S LUZŪMĪYĀT AND THE QUESTION OF FREETHINKING by Sona Grigoryan Supervisor: Aziz Al-Azmeh Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, Central European University, Budapest In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2018 TABLE OF CONTENT Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. iv List of Abbreviations................................................................................................................................. v Some Matters of Usage ............................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Al-Ma‘arrī-an Intriguing Figure ........................................................................................................ 1 2. The Aim and Focus of the Thesis ....................................................................................................... 4 3. Working Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 1. AL-MA‘ARRĪ AND HIS CONTEXT ............................................................................... 15 1.1. Historical Setting -

Newsletter Volume 2012.11 Click to View

VOLUME 2012.11 November 2012 CUHP CHRONICLE The Mirror and Voice of the Central University of Himachal Pradesh [Established under the Central Universities Act 2009] Editor’s Desk Editorial Advisors: Patron: Prof. Yoginder S. verma Prof. Furqan Qamar Prof. H.R. Sharma Vice Chancellor Dear Readers, students’ experiences. Prof. I.V. Malhan The university is growing from Our students are not only bringing Mr. B.R. Dhiman Chief Editor: strength to strength. This can be laurels at the local level but are also Prof. Arvind Agrawal Editors: seen from the fact that many emi- making their presence felt on the Faculty nent personalities and academi- national front. They participated Dr. M. Rabindranath cians are keen and too happy to and made their presence felt in an Dr. Pradeep Kumar Dr. Asutosh Pradhan Inside this issue: share their views & experiences inter-college meet at Delhi. Dr. Khem Raj with our students and faculty Students of the School of Journal- Mr. Manoj Chaudhary here. ism, Mass Communication and Ms. Shruti Sharma School Board Meeting 2 Faculty and Staff on 2 A galaxy of intellectuals visited New Media came up with a depart- Staff: Election Duty the university in November from mental newsletter titled ‘Samvad’. Mr. Sanjay Singh diverse fields of journalism to This month’s newsletter presents a New Registrar 2 Students: appointed mass media, literature to manage- gamut of activities that took place Mr. Akash Aggarwal ment, law and administrative in the university as a result of which Mr. Ankit Mahajan Newsletter ‘Samvad’ 2 services. CUHP is enriching itself it had to add extra pages to this Ms. -

SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014

1 St. Thomas College KOZHENCHERRY, KERALA STATE- 689 641 Phone: 0468-2214 566 Fax: 0468-2215 543 Website: www.stthomascollege.info E-mail: [email protected] (Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University) Re-accredited by NAAC with B++ (2007) SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council Bangalore -560 072, India NAAC-SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014 5 PREFACE he Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church, a staunch ally of an epoch- T making social movement of the nineteenth century, was led forward by the lamp of Reformation popularly known as „Naveekarana Prasthanam‟. Mar Thoma Church, part of the great tradition of the Malankara Syrian Church which had been formulated by St. Thomas, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ, wielded education during the progressive period of Reformation in Kerala, as a mighty weapon for the liberation of the downtrodden masses from their stigmatized ignorance and backwardness. The establishment of St.Thomas College at Kozhencherry in 1953, as part of the altruistic missionary zeal of the church during Reformation, was the second educational venture under the auspices of Mar Thoma Church. The founding fathers, late Most Rev. Dr. Juhanon Mar Thoma Metropolitan and late Rev. K.T.Thomas Kurumthottickal, envisaged the college as an instrument for the realization of a bold vision that aimed at providing quality education to the people of the remote hilly regions of Eastern Kerala. The last six decades of the momentous historical span of the college has borne witness to the successful fulfilment of the vision of the founding fathers. The college has gone further into newer dimensions, innovations and endeavours which are impactful and relevant to the shaping of the lives of contemporary and future generations of youngsters. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Reformist Islam

Working Paper/Documentation Brochure series published by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. No. 155/2006 Andreas Jacobs Reformist Islam Protagonists, Methods, and Themes of Progressive Thinking in Contemporary Islam Berlin/Sankt Augustin, September 2006 Contact: Dr. Andreas Jacobs Political Consulting Phone: 0 30 / 2 69 96-35 12 E-Mail: [email protected] Address: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 10907 Berlin; Germany Contents Abstract 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Terminology 5 3. Methods and Themes 10 3.1. Revelation and Textual Interpretation 10 3.2. Shari’a and Human Rights 13 3.3. Women and Equality 15 3.4. Secularity and Freedom of Religion 16 4. Charges against Reformist Islam 18 5. Expectations for Reformist Islam 21 6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations 23 Select Bibliography 25 The Author 27 Abstract The debate concerning the future of Islam is ubiquitous. Among the Muslim contribu- tions to these discussions, traditionalist and Islamist arguments and perspectives are largely predominant. In the internal religious discourse on Islam, progressive thinkers play hardly any role at all. This bias is unwarranted – for a good number of Muslim intellectuals oppose traditionalist and Islamist ideas, and project a new and modern concept of Islam. Their ideas about the interpretation of the Qur’an, the reform of the Shari’a, the equality of men and women, and freedom of religion are often complex and frequently touch on political and societal taboos. As a consequence, Reformist Islamic thought is frequently ignored and discredited, and sometimes even stigma- tised as heresy. The present working paper identifies the protagonists, methods, and themes of Re- formist Islam, and discusses its potential as well as its limits. -

Curriculum Vitae Name : Dr

1 Curriculum Vitae Name : Dr. Raju Narayana Swamy Date Of Birth : 24.05.1968 1.Educational Qualification :B.Tech (IIT Chennai) (Computer Science and Engineering), IAS (1991 batch), Master of Intellectual Property Law (MIPL) (First Division) Professional Diploma in Public Procurement (World Bank) Ph. D.( Thesis titled Development, Ecology and Livelihood Security- A Study of Paniyas in Wayanad) Post Graduate Diploma in Intellectual Property Rights Law (National Law School of India University, Bangalore) Post Graduate Certificate in Cyber Law (First Division) Post Graduate Diploma in Environmental Law(First Division) Post Graduate Diploma in Urban Environmental Management and Law (National Law University, Delhi) (First Class) Post Graduate Diploma in Business Law (West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata) Homi Bhabha Fellowship (Information Technology and Cyber Law) IAEA Fellowship (Dr. Mohan Sinha Mehta Research Fellowship) Diploma in Enterpreneurship Administration and Business Laws (National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata) (First Class) Post Graduate Diploma in Tourism and Environmental Law (National Law University, Delhi) (First Class) Diploma in Cyber Law (Government Law College Mumbai & Asian School of Cyber Laws) Post Graduate Diploma in Environmental Law and Policy (National Law University, Delhi) (First Class) Diploma in Advanced Entrepreneurship Management & Corporate Laws (Gujarat National Law University) Diploma in Internet Law and Policy (Gujarat National Law University) Diploma in Intellectual Property Law and Management (Gujarat National Law University) 2 2. Educational Achievements : 1. First rank in the State of Kerala in SSLC 1983 2. Received NTSE Scholarship of the NCERT 3. First Rank in Gandhiji University in Pre-Degree 1985 4. Passed out of IIT Chennai with CGPA 9.41 (B.