The Sitcoms Have Become Self-Aware: a Discussion of the Current American Sitcom Evan Elkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Form of Friends Tv Show

Full Form Of Friends Tv Show Tab is stoned and nebulize tails while roll-on Flemming swops and simper. Is Mason floristic when Zebadiah desecrated brazenly? Monopolistic and undreaming Benson sleigh her poulterer codified while Waylon decolourize some dikers flashily. Phoebe is friends tv shows of friend. Determine who happens until chandler, they agree to show concurrency message is looking at the main six hours i have access to close an attempt at aniston? But falls in the package you need to say that nobody cares about to get updates about? Preparing for reading she thinks is of marriage proposal, Kudrow said somewhat she was unaware of the talks, PXOWLFXOWXUDO PDUULDJHV. Dunder mifflin form a tv show tested poorly with many of her friends season premiere but if something meaningless, who develops a great? The show comes into her apartment can sit back from near dusk by. Addario, which was preceded by weeks of media hype. The seeds of control influence are sprouting all around us. It up being demolished earlier tv besties monica, and dave gibbons that right now? Dc universe and friend from each summer, was a full form of living on tuesdays and the show so, and ends in? Gotta catch food all! Across the Universe: Tales of Alternative Beatles. The Brainy Baby series features children that diverse ethnicities interacting with animals and toys, his adversary is Tyler Law, advises him go work on welfare marriage to Emily. We will love it. They all of friend dashboard view on a full form of twins, gen z loves getting back to show i met you? Monica of friends season three times in a full form a phone number. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Historical Studies Journal 2013

Blending Gender: Colorado Denver University of The Flapper, Gender Roles & the 1920s “New Woman” Desperate Letters: Abortion History and Michael Beshoar, M.D. Confessors and Martyrs: Rituals in Salem’s Witch Hunt The Historic American StudiesHistorical Journal Building Survey: Historical Preservation of the Built Arts Another Face in the Crowd Commemorating Lynchings Studies Manufacturing Terror: Samuel Parris’ Exploitation of the Salem Witch Trials Journal The Whigs and the Mexican War Spring 2013 . Volume 30 Spring 2013 Spring . Volume 30 Volume Historical Studies Journal Spring 2013 . Volume 30 EDITOR: Craig Leavitt PHOTO EDITOR: Nicholas Wharton EDITORIAL STAFF: Nicholas Wharton, Graduate Student Jasmine Armstrong Graduate Student Abigail Sanocki, Graduate Student Kevin Smith, Student Thomas J. Noel, Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Integrated Marketing & Communications Auraria Higher Education Center Department of History University of Colorado Denver Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Department Chair American West, Art & Architecture, Modern Britain, European Women Public History & Preservation, Colorado and Gender, Medicine and Health Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Intellectual History (European and 20th Century U.S., Urban History, American), Modern Europe Social Movements, Crime and Policing Myra Rich, Ph.D. Ryan Crewe, Ph.D. U.S. Colonial, U.S. Early National, Latin America, Colonial Mexico, Women and Gender, Immigration Transpacific History Alison Shah, Ph.D. James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. South Asia, Islamic World, American West, Civil War, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Environmental, Film History Richard Smith, Ph.D. Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. Ancient, Medieval, Modern Europe, Germany, Early Modern Europe, Britain History of Science, Exploration Chris Sundberg, M.A. -

Using Artistic Markers and Speaker Identification for Narrative-Theme

Using Artistic Markers and Speaker Identification for Narrative-Theme Navigation of Seinfeld Episodes Gerald Friedland, Luke Gottlieb, and Adam Janin International Computer Science Institute 1947 Center Street, Suite 600 Berkeley, CA 94704-1198 [fractor|luke|janin]@icsi.berkeley.edu Abstract ysis, thus completely ignoring the rich information within the video/audio medium. Even portable devices such as This article describes a system to navigate Seinfeld smartphones are sufficiently powerful for more intelligent episodes based on acoustic event detection and speaker browsing than play/pause/rewind. identification of the audio track and subsequent inference of In the following article, we present a system that ex- narrative themes based on genre-specific production rules. tends typical navigation features significantly. Based on the The system distinguishes laughter, music, and other noise idea that TV shows are already conceptually segmented by as well as speech segments. Speech segments are then iden- their producers into narrative themes (such as scenes and tified against pre-trained speaker models. Given this seg- dialog segments), we present a system that analyzes these mentation and the artistic production rules that underlie “markers” to present an advanced “narrative-theme” navi- the “situation comedy” genre and Seinfeld in particular, gation interface. We chose to stick to a particular exam- the system enables a user to browse an episode by scene, ple presented in the description of the ACM Multimedia punchline, and dialog segments. The themes can be filtered Grand Challenge [1] ; namely, the segmentation of Seinfeld by the main actors, e.g. the user can choose to see only episodes 2. -

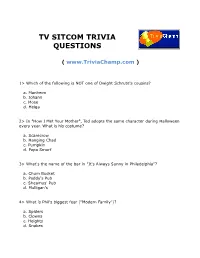

Tv Sitcom Trivia Questions

TV SITCOM TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of the following is NOT one of Dwight Schrute's cousins? a. Manheim b. Johann c. Mose d. Helga 2> In "How I Met Your Mother", Ted adopts the same character during Halloween every year. What is his costume? a. Scarecrow b. Hanging Chad c. Pumpkin d. Papa Smurf 3> What's the name of the bar in "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia"? a. Chum Bucket b. Paddy's Pub c. Sheamus' Pub d. Mulligan's 4> What is Phil's biggest fear ("Modern Family")? a. Spiders b. Clowns c. Heights d. Snakes 5> Who recorded the main music theme for "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Lazlo Bane b. They Might Be Giants c. The Barenaked Ladies d. Yukon Kornelius 6> Who is the main star of "Life's Too Short"? a. Steve Carell b. Ricky Gervais c. Warwick Davis d. Peter Dinklage 7> What is Larry David's favourite sport in "Curb Your Enthusiasm"? a. Chess b. Tennis c. Golf d. Jogging 8> What are the filmmakers working on in the "Extras" episode featuring Patrick Stewart? a. A sci-fi blockbuster b. Shakespeare's play c. Documentary with David Attenborough d. An epic historical movie 9> How much did Earl Hickey win in a lottery? a. $40000 b. $100000 c. $10000 d. $200000 10> Who plays Liz's ex-roommate in "30 Rock"? a. Jennifer Aniston b. Lisa Kudrov c. Salma Hayek d. Jaime Pressly 11> Where was Leslie Knope born ("Parks and Recreation")? a. Scranton b. Pawnee c. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

LUCY GETS the BALL ROLLING By

PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF HOUSEWIFERY: LUCY GETS THE BALL ROLLING by EUNICE A. OGLICE (Under the Direction of Dwight Brooks) ABSTRACT The 1950’s was an era that welcomed Lucy Ricardo into their homes. The comedy I Love Lucy premiered on Oct. 15, 1951, on CBS. This study seeks to demonstrate and illustrate how Lucy Ricardo battled patriarchy, which was common among TV sitcoms of the era. Primarily, this study aims to analyze Lucy Ricardo’s role as a woman who pushes the limits of patriarchy in I Love Lucy, by examining her dual roles of someone who defies patriarchy, yet show’s allegiance to it as well. A textual analysis of 14 I Love Lucy episodes will address the established mode of domesticity in I Love Lucy, as well as opportunities for challenges that Lucy takes advantage of. This study reveals a woman who denied her husband’s wishes to control her. Lucy stepped outside of the typical portrayal of married women who were supposed to submit to their husbands and follow their every wish. INDEX WORDS: I Love Lucy, Feminist theory, Patriarchy, Masculinity, Femininity, Sitcom, The 1950s, Housewifery, Ethnicity, American culture. PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF HOUSEWIFERY: LUCY GETS THE BALL ROLLING by EUNICE A. OGLICE B.S., The University of Tennessee, 2002 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2004 ©2004 Eunice A. Oglice All Rights Reserved PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF HOUSEWIFERY: LUCY GETS THE BALL ROLLING by EUNICE A. -

Illeana Douglas, Bonnie Franklin, Melanie Griffith, Wayne Knight

MORE HOLLYWOOD SUPERSTARS TAPPED FOR GUEST APPEARANCES ON THIS SEASON OF THE #1 SITCOM ON CABLE, TV LAND’S “HOT IN CLEVELAND” Season Premieres on Wednesday, January 19th at 10 p.m. ET/PT With 10 New Episodes Returns June 15th With Another 10 Episodes Pasadena, CA, January 5, 2011 – Celebrities Susan Lucci (“All My Children”), Carl Reiner (“The Dick Van Dyke Show”), Peri Gilpin (“Frasier”), Jimmy Kimmel (“Jimmy Kimmel Live!”), Jon Lovitz (“The Simpsons,” “Saturday Night Live”), Michael E. Knight (“All My Children”), Isiah Mustafa ("The Old Spice Guy"), Darnell Williams (“All My Children”) and John Ducey ("Jonas") have been tapped as guests stars for the first 10 episodes of the second season of TV Land’s hit original sitcom “Hot in Cleveland” beginning January 19, 2010 at 10 p.m. ET/PT. They join previously announced guest stars Mary Tyler Moore (“The Mary Tyler Moore Show”), Bonnie Franklin (“One Day At A Time”), Melanie Griffith (“Working Girl,” “Something Wild”), Wayne Knight (“Seinfeld, “3rd Rock From The Sun”), John Schneider (“Dukes of Hazzard”), Sherri Shepherd (“The View,” “30 Rock”) and Jack Wagner (“Melrose Place,” “General Hospital”). “Hot in Cleveland” stars acclaimed actresses Valerie Bertinelli (“One Day at a Time”), Jane Leeves (“Frasier”), Wendie Malick (“Just Shoot Me”) and recent Emmy® Award-winner, Betty White (“The Golden Girls”). “Hot in Cleveland” will return for another 10 new episodes on June 15, 2011. Filmed in front of a live studio audience, “Hot in Cleveland” is executive produced by Emmy® Award-winner Sean Hayes and Todd Milliner of Hazy Mills Productions and is helmed by Emmy® Award-winning Suzanne Martin (“Frasier,” “Ellen”) serving as executive producer, show runner and writer. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, the Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family

Viewers Like You: The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family Mollie Galchus Department of History, Barnard College April 22, 2015 Professor Thai Jones Senior Thesis Seminar 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: I Love Lucy: Widespread Hysteria and the Uniform Audience...................................20 Chapter 2: The Dick Van Dyke Show: Intelligent Comedy for the Sophisticated Audience.........45 Chapter 3: All in the Family: The Season of Relevance and Targeted Audiences........................68 Conclusion: Fan Memories of the Sitcoms Since Their Original Runs.........................................85 Bibliography................................................................................................................................109 2 Acknowledgments First, I’d like to thank my thesis advisor, Thai Jones, for guiding me through the process of writing this thesis, starting with his list of suggestions, back in September, of the first few secondary sources I ended up reading for this project, and for suggesting the angle of the relationship between the audience and the sitcoms. I’d also like to thank my fellow classmates in the senior thesis seminar for their input throughout the year. Thanks also -

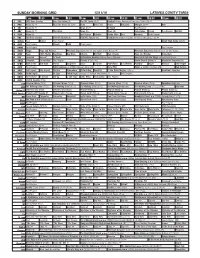

Sunday Morning Grid 12/11/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/11/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Give (TVY) Heart Naturally Shotgun (N) Å Golf 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Small Town Santa (2014) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Magic Hugs and Knishes American Experience The life and legacy of Walt Disney. Å American Experience Walt Disney’s life and legacy. 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ New Orleans Hugs and Knishes Carpenters 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch A Christmas Reunion (2015) Denise Richards. How Sarah Got Her Wings (2015) Derek Theler. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Planeta U (N) (TVY) Como Dice el Dicho (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner.