Island Baroque Border Crossing Started with an Unsatisfied Audience Member

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saints Alive

Welcome to Saints Alive For centuries the faith of our brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers has been fashioned, refined, colored and intensified by the sheer variety and passion of the lives of the great Christian saints. Their passions, their strengths and weaknesses, the immense variety of their lives have intrigued children young and old for ages. You may even have been named for a particular saint – Dorothy, Dolores, Anne or Elizabeth; Malachi, Francis or even Hugh. So why not celebrate some of those remarkable people through music? As we resume our trek along the Mission Road, we high- light music written in the Americas to celebrate the life and work of our city’s patron saint, Francis, as well as the lives and mission of other men and women venerated by the great musical masters. Saint Cecilia, patroness of music, is very much alive and present in a setting of “Resuenen los cla- rines” by the Mexican Sumaya. Bassani, an Italian who thrived in Bolivia when it was still called Upper Peru, pays homage to Saint Joseph in a Mass setting bearing his name. Its blend of self-taught craftsmanship and mastery of orchestration is fascinating, intriguing, even jolly. It’s as if Handel and the young Mozart had joined hands, jumped on a boat and headed to the heart of South America. What a nice addition to our library! Chants taught by the zealous, mission-founding Sancho have been sent our way – chants in his own hand, no less. Ignatius Loyola is represented by three short motets (that’s almost too glamorous a name for them, they are more folkish in their style) from Bolivia. -

Tral, and South America and the Caribbean

he region of Latin America is generally defi ned as the compilation of forty-two T independent nations from North, Cen- tral, and South America and the Caribbean. It represents an eclectic conglomerate of cultures with a common point of origin: the interaction between European colonizers, African slaves, and Native Americans following the arrival of Christopher Co- lumbus in 1492. Given time, each nation developed cultural traits that made them unique while continu- ing to share certain common traits. Music is one expression of this cultural back- ground. In the specifi c case of Latin American choral music, compositions are generally associated with festive and energetic characters, up-tempo music, and complex rhythms, often accompanied by folk or popular instruments—generally percussion and sometimes stringed instruments such as guitar, cuatro, charango, tres, vihuela, among many other variants of the Spanish Guitarrilla or the Portuguese Machete. With certainty, much of the choral repertoire from this region fi ts this description. There is also, however, a vast and signifi cant catalog of works written by Latin American composers that is unaccompanied or accompanied by piano or organ. Moreover, there is an important catalog of works for choir and orches- tral forces (large orchestras or chamber ensembles) that generally—but not always—represents a syn- cretism of western compositional techniques and regional cultural fl avors (melodies, rhythmic patterns, harmonic cadences, colors and textures, and at times folkloric instruments) from each particular country. Following is a brief exploration of this latter group of compositions written by Latin American authors for choirs and symphonic ensembles. -

Download Booklet

Journeys to the New World were born in Spain and were trained in music JOURNEYS TO THE NEW WORLD Old Spain to New Spain there; they held appointments in Spain and later HISPANIC SACRED MUSIC FROM THE emigrated to the new colonial cities. One more This is a musical trip from the mid-sixteenth became the first composer-choirmaster to be 16th & 17th CENTURIES century to around 1700, involving music in Late born there of Spanish parents, thus criollo. Renaissance style, carrying Spanish Catholicism across the Atlantic to supplant an indigenous Cristóbal de Morales (d.1553) was a Sevillian 1 Regina caeli laetare à 6 Cristóbal de Morales (c.1500 – 1553) [4.30] culture. Once the invasion had taken root with the who spent ten years away in Rome at the Sistine 2 Salve regina à 5 Hernando Franco (1532 – 1585) [9.36] conquest of Tenochtitlán and its transformation Chapel. Tomás Luis de Victoria (d.1611) who 3 Vidi speciosam Tomás Luis de Victoria (c.1548 – 1611) [5.58] to Mexico City, the country became the target of came from Ávila in Castile spent twenty years in 4 Trahe me post te Francisco Guerrero (1528 – 1599) [4.50] fervent friars and preachers. Franciscans were Rome and published most of his works in Italy. first in 1523, then Dominicans, all fired with Francisco Guerrero and Alonso Lobo were from 5 Versa est in luctum Alonso Lobo (1555 – 1617) [4.47] Christian zeal to convert the native population. Seville or nearby. Guerrero spent his mature 6 Circumdederunt me Juan Gutierrez de Padilla (c.1590 – 1664) [4.16] From the outset they used music to great effect. -

A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico During the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Valenzuela, Eladio III, "A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2797. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2797 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS ELADIO VALENZUELA III Department of Music APPROVED: ____________________________________ William McMillan, D.A., CHAIR ____________________________________ Elisa Fraser Wilson, D.M.A. ____________________________________ Curtis Tredway, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Allan D. McIntyre, M.Ed. _______________________________ Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS BY ELADIO VALENZUELA III, B.M., M.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS EL PASO MAY 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I want to thank God for the patience it took to be able to manage this project, my work, and my family life. -

DE CÓMO UNA LETRA HACE LA DI.ERENCIA En 1934 El Doctor

DE CÓMO UNA LETRA HACE LA DIERENCIA LAS OBRAS EN NÁHUATL ATRIBUIDAS A DON HERNANDO RANCO ELOY CRUZ En 1934 el doctor Gabriel Saldívar y Silva (1909-1980) con la colabo- ración de su esposa, la maestra Elisa Osorio Bolio de Saldívar, publicó Historia de la Música en México, una obra pionera en su campo. Entre las muchas virtudes de este libro puede citarse las siguientes: a) Es la primera obra dedicada al estudio de la música en México durante los siglos XVI-XIX.1 b) Para su realización se consultó documentos originales; según de- clara el propio Saldívar, él y su esposa recurrieron al Archivo General de la Nación, al Museo Nacional de Historia, al Archivo del Ayunta- miento de la ciudad de México y a los archivos de la Catedral Metro- politana y otras iglesias capitalinas.2 c) El autor tomó en cuenta la música prehispánica, no se contentó con asumir que la música mexicana comienza con la llegada de los españoles. d) En esta obra, Saldívar reconoce la influencia que la música de los negros pudo tener en el desarrollo de la música en nuestro país. e) Saldívar consideró que ningún panorama de la música nacional podía estar completo si no se hacía también un reconocimiento de la música popular; así, en el libro encontramos referencias no solo de las misas de la época colonial y de la Academia ilarmónica Mexicana del Quiero dar mi más cumplido agradecimiento a todas las personas que me ayudaron en la elaboración de este artículo: Karen Dakin, Clotilde Martínez, Concepción Abellán, Gabriela Villa, Mauricio Beuchot, Tarsicio Herrera, Antonio Corona, Hector Rogel, Gabriela Tinoco, Irma Guadalupe Cruz, Salvador Díaz Cíntora, Ricardo Valenzuela y Aurelio Tello. -

A COLONIAL NAHUATL HYMN to the VIRGIN Alfred E. Lemmon* from Canadal to Argentina,2 Religious Chroniclers Wrote Glowingly Of

A COLONIAL NAHUATL HYMN TO THE VIRGIN Alfred E. Lemmon* From Canadal to Argentina,2 religious chroniclers wrote glowingly of how missionaries translated various Christian prayers into Indian languages and then set them to music. Beginning with Pedro de Gante in Mexico3 and Francisco Solano in Argentina,' innumerable missionaries found music an invaluable aid in the conversion of the Indians to Catholicism. Perhaps, no missionary stated the case more simply than Juan María Salvatierra, who in asking to be sent to the missions, stated that his skills as a musician would be of immense value in his work among the natives.5 Yet, whether it be Northern Mexico, Brazil, or Paraguay only a handful of religious texts in Indian languages set to music survive. Robert Stevenson in Music in Mexico surveyed the writings * The author would like to thank Mrs. Martha B. Robertson of the Tulane Latin American Library for bringing this Nahuatl hymn to his attention. He would also like to thank Mr. Joseph Eugene Gibson and Ms. Catherine Thompson for their assistance. 1 The following works give valuable information on Canada, the United States, and Northern Mexico: Clement J. McNaspy, "Iroqouis Challenge; Chant in Approved Vernacular", Orate Fratres, xxi, (May, 1947), 323-327. Robert Stevenson, "Written Sources for Indian Music until 1882", Ethnomusicology, xvii, (January, 1973), 1-40. , "English Sources for Indian Music until 1882", Ethnomusicology, XVII, (September, 1973), 399-442. David E. Crawford, "The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, Early Sources for an Ethnography of Music among American Indians", Ethnomusicology, xi, (May, 1967), 199-206. Lincoln B. -

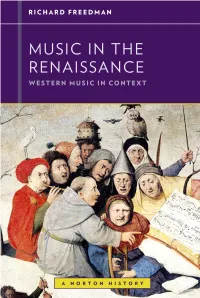

MUSIC in the RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Richard Freedman Haverford College n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY Ƌ ƋĐƋ W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program—trade books and college texts— were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: Bonnie Blackburn Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics-Fairfield, PA A catalogue record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-393-92916-4 W. -

Cinco Nuevos Libros De Polifonía En La Catedral Metropolitana De México*

ARCHIVOS Y DOCUMENTOS CINCO NUEVOS LIBROS DE POLIFONÍA EN LA CATEDRAL METROPOLITANA DE MÉXICO* Javier MARÍN LÓPEZ** Universidad de Granada INTRODUCCIÓN Incontables tesoros musicales han desaparecido a lo largo de los siglos y especialmente durante las revoluciones más modernas, no sólo en México, sino en toda Hispanoaméri• ca. Diversos inventarios sobre los fondos musicales y las referencias en la literatura más antigua (general o especí- * Esta aportación se enmarca dentro de un trabajo más amplio que bajo el título de "Música y músicos españoles en México durante la épo• ca virreinal (1521-1821)" fue realizado con el generoso patrocinio de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores de México, cuya beca del Programa Especial "Genaro Estrada" para mexicanistas me permitió investigar en diferentes archivos de la ciudad de México durante tres meses (julio a septiembre de 2002). Conste, en primer lugar, mi agradecimiento a la mencionada institución. También deseo expresar mi más sincero agra• decimiento al padre Luis Ávila Blancas, canónigo archivero de la cate• dral de México, y al licenciado Salvador Valdez Ortiz, encargado de atención al público, por la ayuda prestada durante mi investigación en la catedral. Agradezco el interés mostrado por mi trabajo y su sugeren• cia de publicar la presente colaboración al doctor Óscar Mazín Gómez, de El Colegio de México. Finalmente, Quiero exoresar mi gratitud al doc• tor Miguel A. Marín (Universidad de La Riojafpor la paciente revisión del artículo, así como a mi director de tesis, doctor Emilio Ros Fábreeas (Universidad de Granada) por sus innumerables sugerencias antes y durante la realización del mismo. ** Doctorando del Departamento de Historia del Arte, Área de His• toria y Ciencias de la Música, Universidad de Granada (España). -

Improvisation and Polyphony in Colonial Mexico

Improvisation and Polyphony in Colonial Mexico Adam Salmond Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal December 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology © Adam Salmond i Table of Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgements iv Introduction v Chapter 1: Historical Context 1 Chapter 2: Improvisation in Renaissance Europe 23 Chapter 3: Music and the Franciscan Mission 35 Chapter 4: Improvisation at Mexico City Cathedral 58 Chapter 5: Techniques of Improvisation in Mexican Compositions 82 Conclusion 110 Bibliography 116 ii Abstract When Spain colonized Mesoamerica, it imported a European musical tradition that grew rapidly in the New World. Previous scholarship has traced the dissemination of composed European polyphony in New Spain, but has overlooked the concomitant emergence of an oral practice of improvising counterpoint. The tradition of improvised counterpoint, especially prominent in Spain, also developed in colonial Mexico. According to the chronicler Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola (1562 – 1631), the conquistadors sang Masses in improvised counterpoint as early as 1519. The Franciscan friar Jacobo de Testera wrote to Charles V in 1533 that the Nahua were learning to improvise in colleges established by missionaries. Finally, the records and legislation of Mexico City Cathedral testify to the practice of improvisation at New Spain’s foremost church. This study traces the development of contrapuntal improvisation in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Mexico, while also re-appraising the role of music in the colonization of New Spain. Chapter 1 begins by providing a historical context and by examining the discussions of music in mid-sixteenth-century Spanish debates over the legitimacy of enslaving Mesoamericans. -

Música Local Y Música Foránea En Los Libros De Polifonía De Las Catedrales De Guatemala Y México

Omar Morales Abril Música local y música foránea en los libros de polifonía de las Catedrales de Guatemala y México Introducción La conquista y colonización del Nuevo Mundo por parte de la corona española trajo consigo, en lo que respecta a la jurisdicción eclesiástica, la división y delimi- tación del territorio en unidades de administración diocesana.1 En esta primera etapa de organización de la iglesia católica en América, el modelo litúrgico de la catedral de Sevilla jugó un papel preponderante. El obispado de México fue erigido en 1530 y, cuatro años después, el de Guatemala, ambos sufragáneos de la arquidiócesis de Sevilla. La sede mexicana fue elevada a metropolitana en 1546 y la de Guatemala pasó a ser sufragánea de ella desde entonces hasta 1745, que fue a su vez elevada a sede arquidiocesana.2 Pero el referente sevillano per- siste en los acuerdos capitulares tanto en la catedral de México como en la de Guatemala.3 Las bulas de fundación de ambas diócesis citan las constituciones, oficios, festividades, ceremonial y tradiciones de la sede hispalense. Pero las pro- pias bulas dejan la puerta abierta a la adopción de otras prácticas ceremoniales, pudiendo «libremente reducirlas o trasplantarlas a su iglesia catedral, para lustre y 1 Peter Gerhard, Geografía Histórica de la Nueva España, 1519–1821, México, Unam, 1986, pp. 17–19. 2 Mariano Cuevas, Historia de la Iglesia en México, vol. 1, México, Editorial Patria, 1946, pp. 124– 125; Domingo Juarros, Compendio de la historia de la ciudad de Guatemala (1818), 3ª. ed. tomo I, Guatemala, Tipografía Nacional, 1936, pp. -

Sacred Music, Summer 2008, Volume 135 Number 2

SACRED MUSIC Summer 2008 Volume 135, Number 2 EDITORIAL On the Graduale Romanum and the Papal Masses | William Mahrt 3 ARTICLES One Hundred Years of the Graduale Romanum | John Berchmans Göschl 8 Beyond Medici: The Struggle for Progress in Chant | Anthony Ruff 26 ARCHIVE Gregorian Chant: Its Artistic Value and Its Interpretation | Joseph Lennards 45 REPERTORY Hernando Franco’s Circumdederunt me: The First Piece for the Dead in Early Colonial America | Javier Marín 58 Tallis’s If Ye Love Me | Joseph Sargent 65 DOCUMENTS A Parsing of Two English-Language Translations of Musicam Sacram | David E. Saunders 70 Music and Hope | Benedict XVI 77 COMMENTARY Is Chant for Everyone? | Jeffrey Tucker 79 Musical Illiterarcy Revisited | Quentin Faulkner 86 NEWS 89 LAST WORD The Strange Rejection of the Roman Gradual | Kurt Poterack 91 SACRED MUSIC Formed as a continuation of Caecilia ,published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster , published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233. E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musicasacra.com Editor: William Mahrt Managing Editor: Jeffrey Tucker Editor-at-Large: Kurt Poterack Editorial Assistant: Jane Errera Editorial Help: Richard Rice Typesetting: Judy Thommesen, Richard Rice Membership and Circulation: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President: William Mahrt Vice-President: Horst Buchholz Secretary: Rosemary Reninger Treasurer: William Stoops Chaplain: Rev. Father Robert A. Skeris Directors: Susan Treacy, Jeffrey Tucker, Scott Turkington Directors Emeriti: Rev. -

Navidad Nuestra December 8 & 9, 2018

Navidad Nuestra December 8 & 9, 2018 Mater Dei Sarah Rimkus (b. 1990) Magnificat Tawnie Olson (b. 1971) David Thomson & Ken Short Special guest ensemble Canens Vocem from Columbia High School Jamie Bunce, director Asi Andando (Guatemala) Tomás Pascual (c. 1595-1635) Sarah Thomson Ave Maria (Brazil) Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Gloria a Dios Michael Mendoza (b. 1944) Laura Quinn, Mercedes Pescevich, PJ Livesey, Dan Malloy Canciones de Cuna (Venezuela) Alberto Grau (b. 1937) Canción de Cuna Alice Allen Duérmete apegado a mí O Magnum Mysterium (Venezuela) César Alejandro Carrillo (b. 1957) El Cielo Canta Alegría (Argentina) Pablo Sosa (b. 1933), arr. Ed Henderson (b. 1952) INTERMISSION Dios Itlaçonantzine Don Hernando Franco (fl. 16th cent) The Flight Richard Causton (b. 1971) Rachel Clark & Emilie Bishop Three Christmas Carols (Spain) Francisco Guerrero (1528-1599) Oýd, oýd una cosa Katie Hendrix, Jamie Bunce, Alyssa Casazza Virgen sancta A un niño llorando Mickey McGrath CHAMBER SINGERS Nach grüner Farb mein Herz verlangt Michael Praetorius (c. 1571-1621) The Bird of Dawning Bob Chilcott (b. 1955) Jennifer Holak Legend of the Bird (U.S. Premiere) Stephanie Martin (b. 1962) Semi-Chorus: Kelsey Hubsch, Maria Nicoloso, Kimberly Love, Mickey McGrath, Pam Huelster, Catie Gilhuley, Jamie Vergara Dremlen Feygl Leyb Yampolsky, arr. Joshua Jacobson Brightest and Best arr. Shawn Kirchner (b. 1970) Navidad Nuestra (Argentina) Ariel Ramírez (1921-2010) La Anunciación Holland Jancaitis & Ted Roper La Peregrinación El Nacimiento Nancy Watson-Baker Los Pastores Holland Jancaitis & Ben Schroeder Los Reyes Magos La Huida Nick Herrick, Holland Jancaitis, Ben Schroeder Child of the Poor (Audience) Scott Soper Ask the Watchman arr.