Paul Graham Is an Essayist, Programmer, and Programming Language Designer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Machine That Builds Itself: How the Strengths of Lisp Family

Khomtchouk et al. OPINION NOTE The Machine that Builds Itself: How the Strengths of Lisp Family Languages Facilitate Building Complex and Flexible Bioinformatic Models Bohdan B. Khomtchouk1*, Edmund Weitz2 and Claes Wahlestedt1 *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1Center for Therapeutic Innovation and Department of We address the need for expanding the presence of the Lisp family of Psychiatry and Behavioral programming languages in bioinformatics and computational biology research. Sciences, University of Miami Languages of this family, like Common Lisp, Scheme, or Clojure, facilitate the Miller School of Medicine, 1120 NW 14th ST, Miami, FL, USA creation of powerful and flexible software models that are required for complex 33136 and rapidly evolving domains like biology. We will point out several important key Full list of author information is features that distinguish languages of the Lisp family from other programming available at the end of the article languages and we will explain how these features can aid researchers in becoming more productive and creating better code. We will also show how these features make these languages ideal tools for artificial intelligence and machine learning applications. We will specifically stress the advantages of domain-specific languages (DSL): languages which are specialized to a particular area and thus not only facilitate easier research problem formulation, but also aid in the establishment of standards and best programming practices as applied to the specific research field at hand. DSLs are particularly easy to build in Common Lisp, the most comprehensive Lisp dialect, which is commonly referred to as the “programmable programming language.” We are convinced that Lisp grants programmers unprecedented power to build increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence systems that may ultimately transform machine learning and AI research in bioinformatics and computational biology. -

Paul Graham's Revenge of the Nerds

Paul Graham’s Revenge of the Nerds What made Lisp different Symbols and S-Expression Trees 6. Programs composed of expressions. Lisp programs are trees of expressions, each of which returns a value. … 7. A symbol type. Symbols are effecBvely pointers to strings stored in a hash table. So you can test equality by comparing a pointer, instead of comparing each character. 8. A notation for code using trees of symbols and constants. CS251 Programming [Lyn adds: these trees are called symbolic expressions = s-expressions] Languages 9. The whole language there all the time. There is no real distinction Spring 2018, Lyn Turbak between read-time, compile-time, and runtime. … reading at runtime enables programs to communicate using s-expressions, an idea recently reinvented Department of Computer Science as XML. [Lyn adds: and JSON!] Wellesley College Symbols & S-expressions 2 Symbols TesBng Symbols for Equality: eq? Lisp was invented to do symbolic processing. (This was thought to be the core of ArBficial Intelligence, and disBnguished Lisp from Fortran (the other The key thing we do with symbols is test them for equality main language at the Bme), whose strength with numerical processing.) with eq? (pronounced “eek”). A symbol is eq? to itself and A key Racket value is the symbol. nothing else. The symbol cat is wriNen (quote cat) or 'cat. > (eq? 'cat 'cat) Symbols are values and so evaluate to themselves. #t > 'cat > (map (λ (s) (eq? s 'to)) 'cat (list 'to 'be 'or 'not 'to 'be)) '(#t #f #f #f #t #f) ; 'thing is just an abbreviation for (quote thing) > (quote cat) 'cat Symbols are similar to strings, except they’re atomic; we don’t do character manipulaBons on them. -

Teach Yourself Scheme in Fixnum Days"

http://xkcd.com/224/ CS 152: Programming Language Paradigms Prof. Tom Austin San José State University What are some programming languages? Taken from http://pypl.github.io/PYPL.html January 2016 Why are there so many? Different domains Different design choices • Flexibility • Type safety • Performance • Build time • Concurrency Which language is better? Good language features • Simplicity • Readability • Learn-ability • Safety • Machine independence • Efficiency These goals almost always conflict Conflict: Type Systems Stop "bad" programs … but ... restrict the programmer Why do we make you take a programming languages course? • You might use one of these languages. • Perhaps one of these languages is the language of the future (whatever that means). • You might see similar languages in your job. • Somebody made us take one, so now we want to make you suffer too. • But most of all… We want to warp your minds. Course goal: change the way that you think about programming. That will make you a better Java programmer. The "Blub" paradox Why do I need higher order functions? My language doesn't have them, and it works just fine!!! "As long as our hypothetical Blub programmer is looking down the power continuum, he knows he's looking down… [Blub programmers are] satisfied with whatever language they happen to use, because it dictates the way they think about programs." --Paul Graham http://www.paulgraham.com/avg.html Languages we will cover (subject to change) Administrative Details • Green sheet: http://www.cs.sjsu.edu/~austin/cs152- spring19/Greensheet.html. • Homework submitted through Canvas: https://sjsu.instructure.com/ • Academic integrity policy: http://info.sjsu.edu/static/catalog/integrity.html Schedule • The class schedule is available through Canvas. -

Reading List

EECS 101 Introduction to Computer Science Dinda, Spring, 2009 An Introduction to Computer Science For Everyone Reading List Note: You do not need to read or buy all of these. The syllabus and/or class web page describes the required readings and what books to buy. For readings that are not in the required books, I will either provide pointers to web documents or hand out copies in class. Books David Harel, Computers Ltd: What They Really Can’t Do, Oxford University Press, 2003. Fred Brooks, The Mythical Man-month: Essays on Software Engineering, 20th Anniversary Edition, Addison-Wesley, 1995. Joel Spolsky, Joel on Software: And on Diverse and Occasionally Related Matters That Will Prove of Interest to Software Developers, Designers, and Managers, and to Those Who, Whether by Good Fortune or Ill Luck, Work with Them in Some Capacity, APress, 2004. Most content is available for free from Spolsky’s Blog (see http://www.joelonsoftware.com) Paul Graham, Hackers and Painters, O’Reilly, 2004. See also Graham’s site: http://www.paulgraham.com/ Martin Davis, The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing, W.W. Norton and Company, 2000. Ted Nelson, Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1974. This book is now very rare and very expensive, which is sad given how visionary it was. Simon Singh, The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography, Anchor, 2000. Douglas Hofstadter, Goedel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, 20th Anniversary Edition, Basic Books, 1999. Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 2nd Edition, Prentice Hall, 2003. -

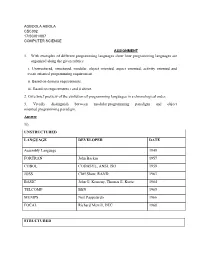

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

A History of Clojure

A History of Clojure RICH HICKEY, Cognitect, Inc., USA Shepherd: Mira Mezini, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany Clojure was designed to be a general-purpose, practical functional language, suitable for use by professionals wherever its host language, e.g., Java, would be. Initially designed in 2005 and released in 2007, Clojure is a dialect of Lisp, but is not a direct descendant of any prior Lisp. It complements programming with pure functions of immutable data with concurrency-safe state management constructs that support writing correct multithreaded programs without the complexity of mutex locks. Clojure is intentionally hosted, in that it compiles to and runs on the runtime of another language, such as the JVM. This is more than an implementation strategy; numerous features ensure that programs written in Clojure can leverage and interoperate with the libraries of the host language directly and efficiently. In spite of combining two (at the time) rather unpopular ideas, functional programming and Lisp, Clojure has since seen adoption in industries as diverse as finance, climate science, retail, databases, analytics, publishing, healthcare, advertising and genomics, and by consultancies and startups worldwide, much to the career-altering surprise of its author. Most of the ideas in Clojure were not novel, but their combination puts Clojure in a unique spot in language design (functional, hosted, Lisp). This paper recounts the motivation behind the initial development of Clojure and the rationale for various design decisions and language constructs. It then covers its evolution subsequent to release and adoption. CCS Concepts: • Software and its engineering ! General programming languages; • Social and pro- fessional topics ! History of programming languages. -

CS302 2007S : Paul Graham

Programming Languages (CS302 2007S) Paul Graham - Revenge of the Nerds Comments on: Graham, Paul (2002). Revenge of the Nerds. Online resource available at http: //www.paulgraham.com/icad.html. Paul Graham talks about macros in LISP in his article. On trying to look for definition of macros I ran into the following quote at http://www.apl.jhu.edu/~hall/Lisp-Notes/Macros.html: Lisp functions take Lisp values as input and return Lisp values. They are executed at run-time. Lisp macros take Lisp code as input, and return Lisp code. They are executed at compiler pre-processor time, just like in C. The resultant code gets executed at run-time. In other words, isn’t the concept of macros in LISP the core idea of the funtional programming paradigm although it generalizes the concept of higher order procedures? How is it different otherwise? Not quite. Macros work with the source code. Higher-order procedures cannot actually get into the internals of a procedures. This paper makes a great argument as to why scheme is so powerful. The constant Dilbert reference only drives his point. He also reiterates the point made in other readings that the language that is fashionable at a certain moment is not necessarily the most powerful one. Aside from shorter code, I don’t really understand what he means by power? You have mentioned in class that pretty much all modern languages have the same computational power. So what makes scheme more powerful that the fact that you will take less time typing your code? Does it perhaps excersise the brain in a different way that other languages? By power, I think he means the number of things that you can express easily. -

Logo Tree Project

LOGO TREE PROJECT Written by P. Boytchev e-mail: pavel2008-AT-elica-DOT-net Rev 1.82 July, 2011 We’d like to thank all the people all over the globe and all over the alphabet who helped us build the Logo Tree: A .........Daniel Ajoy, Eduardo de Antueno, Hal Abelson B .........Andrew Begel, Carl Bogardus, Dominique Bille, George Birbilis, Ian Bicking, Imre Bornemisza, Joshua Bell, Luis Belmonte, Vladimir Batagelj, Wayne Burnett C .........Charlie, David Costanzo, John St. Clair, Loïc Le Coq, Oliver Schmidt-Chevalier, Paul Cockshott D .........Andy Dent, Kent Paul Dolan, Marcelo Duschkin, Mike Doyle E..........G. A. Edgar, Mustafa Elsheikh, Randall Embry F..........Damien Ferey, G .........Bill Glass, Jim Goebel, H .........Brian Harvey, Jamie Hunter, Jim Howe, Markus Hunke, Rachel Hestilow I........... J..........Ken Johnson K .........Eric Klopfer, Leigh Klotz, Susumu Kanemune L..........Janny Looyenga, Jean-François Lucas, Lionel Laské, Timothy Lipetz M.........Andreas Micheler, Bakhtiar Mikhak, George Mills, Greg Michaelson, Lorenzo Masetti, Michael Malien, Sébastien Magdelyns, Silvano Malfatti N .........Chaker Nakhli ,Dani Novak, Takeshi Nishiki O ......... P..........Paliokas Ioannis, U. B. Pavanaja, Wendy Petti Q ......... R .........Clem Rutter, Emmanuel Roche S..........Bojidar Sendov, Brian Silverman, Cynthia Solomon, Daniel Sanderson, Gene Sullivan, T..........Austin Tate, Gary Teachout, Graham Toal, Marcin Truszel, Peter Tomcsanyi, Seth Tisue, Gene Thail U .........Peter Ulrich V .........Carlo Maria Vireca, Álvaro Valdes W.........Arnie Widdowson, Uri Wilensky X ......... Y .........Andy Yeh, Ben Yates Z.......... Introduction The main goal of the Logo Tree project is to build a genealogical tree of new and old Logo implementations. This tree is expected to clearly demonstrate the evolution, the diversity and the vitality of Logo as a programming language. -

Graduate School 2000-2004 Bulletin

LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL 2000 ❦ 2004 The information in this BULLETIN is made as accurate as is possible at the time of publication. Students are responsible for informing themselves of and satisfactorily meeting all requirements pertinent to their relationship with the University. The University reserves the right to make such changes as circumstances demand with reference to admission, registration, tuition and fees, attendance, curriculum requirements, conduct, academic standing, candidacy, and graduation. BULLETIN OF LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Volume 90, Number 3, March 30, 2002 Published once a month July 15 and once a month December 15, 2001; once a month March 30, 2002; once a month April 15, 2002; and once a month August 30, 2002. Loma Linda, CA 92350 LLUPS 18495 printed on recycled paper Bulletin of the Graduate School 2000-2004 This is a four-year BULLETIN, effective beginning Summer Quarter 2000. Loma Linda University Loma Linda, CA 92350 a Seventh-day Adventist health-sciences university CONTENTS I 7 LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY 8 University Foundations 9 Our Mission 11 Nondiscrimination Policy 12 Affirmative Action 14 The Calendar II 21 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL 22 Letter from the Dean 23 Philosophy and Objectives 24 Admissions Information 27 Programs and Degrees 32 Student Life 36 Policies and General Regulations 39 Financial Information III 41 THE PROGRAMS 43 Anatomy 48 Biochemistry 52 Biology 59 Biomedical and Clinical Ethics 62 Biomedical Sciences 63 Case Management 64 Clinical Mediation 65 Clinical Ministry 69 Dentistry 83 -

Basic Lisp Techniques

Basic Lisp Techniques David J. Cooper, Jr. February 14, 2011 ii 0Copyright c 2011, Franz Inc. and David J. Cooper, Jr. Foreword1 Computers, and the software applications that power them, permeate every facet of our daily lives. From groceries to airline reservations to dental appointments, our reliance on technology is all-encompassing. And, it’s not enough. Every day, our expectations of technology and software increase: • smart appliances that can be controlled via the internet • better search engines that generate information we actually want • voice-activated laptops • cars that know exactly where to go The list is endless. Unfortunately, there is not an endless supply of programmers and developers to satisfy our insatiable appetites for new features and gadgets. Every day, hundreds of magazine and on-line articles focus on the time and people resources needed to support future technological expectations. Further, the days of unlimited funding are over. Investors want to see results, fast. Common Lisp (CL) is one of the few languages and development options that can meet these challenges. Powerful, flexible, changeable on the fly — increasingly, CL is playing a leading role in areas with complex problem-solving demands. Engineers in the fields of bioinformatics, scheduling, data mining, document management, B2B, and E-commerce have all turned to CL to complete their applications on time and within budget. CL, however, no longer just appropriate for the most complex problems. Applications of modest complexity, but with demanding needs for fast development cycles and customization, are also ideal candidates for CL. Other languages have tried to mimic CL, with limited success. -

On Paul Graham Blas Moros

On Paul Graham Blas Moros Intro The hope is that this “teacher’s reference guide” helps highlight the most impactful points from Paul Graham’s essays. Paul Graham is best known for starting and selling a company called Viaweb and later starting a new model for funding early stage startups called Y Combinator. His unique background combined with his experience starting, growing, leading, selling and investing in businesses gives him a fascinating and often surprising outlook on a vast array of topics – from art to philosophy to computer programming to startups. He is one of the few people to have deep fluency in nearly every aspect pertinent to business and has perhaps more experience and better pattern recognition than anybody else. Some key filters I consider in order to figure out what topics to focus on and dive into are universality and timelessness. It is worth spending the most time reading, analyzing, understanding and acting upon the things which don’t change, or at least change relatively slowly. This effort tends to be well spent as it can help expose and develop “invariant strategies.” These strategies are so powerful because they are optimal, timeless and universal. By doing this deep work upfront, you have “pre-paid” in a sense and this can give you the ability and confidence to act and invest in the future when others are retreating. I believe Paul Graham’s essays fall into this category and it was an absolute pleasure digging into and digesting them. One of my favorite essays was How to Do Philosophy (pg. -

Continuations

Advanced Scheme Techniques Advanced Scheme Techniques Some Naughty Bits Jeremy Brown January 7-8, 2003 Page 1 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Advanced Scheme Techniques Acknowledgements Jonathan Bachrach, Alan Bawden, Chris Hanson, Neel Krishnaswami, and Greg Sullivan offered many helpful suggestions. These slides draw on works by Hal Abelson, Alan Bawden, Chris Hanson, Paul Graham, Oleg Kiselyov, Neel Krishnaswami, Al Petrofsky, Jonathan Rees, Dorai Sitaram, Gerry Sussman, Julie Sussman, and the R5RS authors group Thanks also to Scheme Boston, the Boston-area Scheme User’s Group. And of course to SIPB, for organizing. Page 2 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Advanced Scheme Techniques Advanced Scheme Day 2: Continuations Page 3 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Advanced Scheme Techniques Scheme Requests for Implementation (SRFIs) Several of the examples today will refer to SRFIs. The SRFI documents represent the Scheme community’s de facto, post-R5RS standards Check them out at http://srfi.schemers.org/ Page 4 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Advanced Scheme Techniques Anatomy of a Closure In Scheme, procedures are closures. A closure expects to be invoked with a certain number of arguments. A closure contains: a pointer to some code a pointer to an environment Page 5 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Advanced Scheme Techniques Procedure Call When executing function A invokes closure B, A expects to be returned to with a single return value. Page 6 Jeremy H. Brown January 7-8, 2003 Information enabling B to return a value to A must be saved, specifically: a pointer to some code: the return address in A a pointer to an environment: A’s execution environment Taken altogether, the information looks a lot like a closure that expects a single argument! (And never returns.) We call a closure-version of this information a continuation (k).