Güney Afrika Cumhuriyeti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College of Magic – Annual Report 2014

2014College ANNUAL of Magic REPORT 2014 College of Magic Annual Report 1 ANNUAL REPORT for the year ended 31 December 2014 Country of Incorporation South Africa Nature of Organisation The Association is a non-profit organisation incorporated in terms of the Non-profit Organisations Act 1977, on 9 December 1999, Registration Number 007-517 NPO, PBO Number: 930 019 992 Nature of Operations The aim of this organisation is to see lives and communities transformed through the provision of education and development programmes with a specific emphasis on educational enrichment and supplementary tuition targeting the full diversity of the South African Youth. The organisation achieves this objective through the medium of the performing arts, with an emphasis on magic and the allied arts. Street Address 215 Imam Haron Rd (formerly Lansdowne Rd) Claremont 7700 Cape Town South Africa Postal Address PO Box 2479 Clareinch 7740 Cape Town South Africa Telephone +27 21 683 5480 Fax +27 21 683 1970 Website www.collegeofmagic.com Auditors Horwath Zeller Karro Chartered Accountants (S.A.) Registered Accountants and Auditors product, their pricing, where best to perform and how • To enrich the educational experience through to promote it. Many of our graduates have become nurturing confident, balanced, disciplined, professional entertainers and we want ensure that a organised, creative individuals and leaders with core element in our curriculum is to equip our students hope for the future. to be job-makers and to have a positive, transforming • To provide supplementary tuition in order to socio-economic impact throughout their adult lives develop skills in performance, design, teamwork using the skills that they have developed whilst and theatrical & video arts and provide access studying at the College. -

Asmal Fatima 2015.Pdf (1.232Mb)

Demystifying the Muslimah: changing subjectivities, civic engagement and public participation of Muslim women in contemporary South Africa Fatima Asmal A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Social Sciences (Masters) in the Programme of Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2015 1 I, Fatima Asmal (941300984), hereby declare that this is my own work and that all sources that I have used have been acknowledged and referenced. No part of the dissertation has been submitted for any other degree. Any views expressed in the dissertation are those of the author and are in no way representative of those of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. The dissertation has not been presented to any other University for examination, either in the Republic of South Africa, or overseas. Signature: Date: 2 ABSTRACT Demystifying the Muslimah: changing subjectivities, civic engagement and public participation of Muslim women in contemporary South Africa This study interrogates the validity of generalisations about Muslim women. While Islam is undoubtedly important in the lives of most practising Muslim women, rather than regarding their actions and behaviours as governed by Islamic law, the study seeks to historicise their experiences through a life history approach of five women engaged in the civic life of their communities (however widely this may be defined) and in public participation in various ways. Using oral history as a methodology, it investigates what drew these women to civic participation; the nature of their participation in terms of the organisations they are members of and the activities they are involved in; the stimulus for civic engagement and public participation and their achievements in this regard as well as the impact of participation on their identities and subjectivities. -

20 Years CONTENTS

20 Years 20 Th e Ch ild re n ’s H o s p i t a l T r u s t • d G o o i v h i n d l i g h B C a k c CONTENTS Chairman’s Report 2 Financial Review 16 CEO’s Report 4 Children’s Hospital Trust 17 Treasurer’s Report 2014 Trust Successes 6 Statement of Responsibility and Approval 18 2015 Fundraising Initiatives 8 Statement of Financial Position 19 Statement of Comprehensive Income 20 Guardians Programme 10 Statement of Changes in Trust Funds 21 Statement of Cash Flows 22 Circle of Life Legacy Programme 11 Detailed Statement of Comprehensive Income 24 Grateful Hearts 12 Children’s Hospital Foundation 26 Limile’s Story 13 Chairman’s Report Statement of Financial Position 27 The Children’s Hospital Trust SA 14 Statement of Comprehensive Income 28 in the UK Statement of Changes in Trust Funds 29 Statement of Cash Flows 30 Update from the UK Chairman 15 Detailed Statement of Comprehensive Income 31 Donor Report 32 Trust Supporters 36 Boards / Trustees / Committees 38 Trust our Team 39 1 2014 was another year of Late in the year we were also sad to receive the resignation CHAIRMAN’S business as usual for the of Chris Niland as trustee of the Children’s Hospital Trust. Children’s Hospital Trust as As a founding trustee and past chairman of the Trust, Chris’s its numerous projects and contribution to the Hospital can only be described as immense. REPORT programmes once again In truth his resignation is part of a plan of succession that he proceeded according to plan, initiated some time ago, and pursuant thereto we are grateful within budget and on time. -

Materialpresskit2012

1 Contents 1. Film Information 2. Synopsis 3. Director’s Statment 4. Production Note 5. Key Biographies 6. Production Stills 7. Credits For further information, please contact Producer: International Sales Zukrafin Videovision Entertainment Ronnie Apteker Sanjeev Singh [email protected] [email protected] +27 11 575 0999 (ofce) +27 31 204 6000 (ofce) 2 Film Information Title: MATERIAL Format: 35 mm Audio: Dolby Digital Length: 93 minutes 1.Writer/Director: Craig Freimond 2. Producers: Ronnier Apteker Robbie Thorpe 3. Executive Producers: Tendeka Matatu Ivan Epstein Stephen Cohen Anant Singh 4.Co-Producers: Akin Omotso Kgomotso Matsunyane 5. International Sales: Videovision Entertainment 6.Key Cast: Vincent Ebrahim (The Kumars at No.42) Riaad Moosa (Long Walk to Freedom) Joey Rasdien (Bunny Chow) Denise Newman (Shirley Adams, Disgrace) 3 Synopsis Logline: “Life is not a funny business” CASSIM is a young Muslim man working in his father’s (EBRAHIM) textile store. It’s Ebrahim’s dream for Cassim to take over the shop, but Cassim has discovered a talent for stand-up comedy, and he soon finds himself in direct conflict with his father, his family and his community. Synopsis: Cassim Kaif is a young Muslim man who works in his father’s (Ebrahim Kaif) fabric shop. It is Ebrahim’s dream for Cassim to take over the shop. The shop is not in a great part of town and is battling to survive. Ebrahim is embroiled in a thirty-year feud with his brother over a matter of political principle, while the brothers new shop has flourished Ebrahim’s shop is struggling. -

FHS Centenary Commemoration Report.Pdf

‘Looking on into the future …. I see before me as in a vision a great teaching University arising under the shadow of old Table Mountain, and a part of that University is composed of a well-equipped medical Faculty ….’ Barnard Fuller, March 1907 Drafted by Dr Yolande Harley, Ms Linda Rhoda and Ms Esmari Taylor on behalf of the Centenary Management Team Contents 1. PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. CENTENARY KEY MESSAGING, THEMES AND GOALS .......................................................................... 3 3.1 Key messaging for the centenary ........................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Centenary celebration themes ................................................................................................................ 4 3.3 Goals of the centenary celebrations...................................................................................................... 4 4. COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING ...................................................................................................... 5 4.1 Branding – logo and colour scheme ..................................................................................................... 5 4.2 Pamphlet......................................................................................................................................................... -

Local and International Comics Unite in City

The Next 48hOURS ≈ Entertainment Guide Local and international comics unite in City PETER TROMP spoke to RIAAD MOOSA know when this will ever happen again. what is required in the rest of the world. about his new showcase of Muslim com- Usually the only time you see Muslims But I think that’s necessary for improve- ics, ‘The Just Funny Comedy Festival,’ on stage they’re a bridal couple at their ment and mastering your field. showing at the Cape Town International wedding reception. Also, it’s important Convention Centre (CTICC) on Friday to note that even though we’re all Mus- What informs and inspires your com- October 29 at 8.30pm, about unfair ex- lim comedians, we want people of all edy? When are you as sure as you can pectations heaped upon local comedi- religions, cultures and backgrounds to be that something is funny? ans and why non-Muslims shouldn’t feel come to the show. It’s not only for those The audience let’s you know what’s fun- scared off from the festival. who are circumcised and go to mosque ny. Stand-up comedy is a performance on Fridays. art. The material must resonate with the Catch us up about recent develop- audience. Even if the concept is funny, ments in your life. What have you been What is your role in the proceedings, that’s immaterial. If the audience is not busy with, and where has your mind and what material do you have lined laughing or enjoying it, maybe you been at? up for the evening? should think about getting back into My mind is all over the place. -

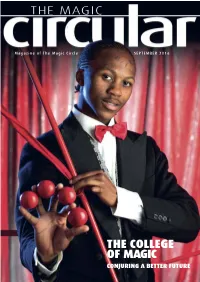

Magic Circular

THE MAGIC Magazine of The Magic Circle SEPTEMBER 2016 THE COLLEGE OF MAGIC CONJURING A BETTER FUTURE THE COLLEGE OF CONJURINGMAGIC A BETTER FUTURE by Guy Hollingworth MIMC “ agic is really alive in South Africa at the Equity boycott. We didn’t have any magic shops. Mmoment,” David Gore, founder and We were not only geographically isolated, but director of the College of Magic, tells me. “We’re we were isolated from seeing magic. So the getting the feel that things are happening.” youngsters who wanted to learn magic didn’t It certainly felt that way when I attended the really have an opportunity.” 2015 SA Magic Convention in October. The That prompted David, at 19, to don top GrandWest Resort and Casino in Cape Town hat and tails, perform some magic for a local was packed with magic enthusiasts and busy newspaper, and announce that he and a professionals from all over the country. colleague were starting the “College of Magic.” Celebrating the College’s 35th birthday Graduates of the College like Stuart Lightbody Its doors opened to 34 students in February and Olwethu Dyantyi gave world-class 1980. performances. Bryan Miles, another graduate, Almost more remarkable than it being a normally be able to mix with young people from was recording a 13-part TV series which is college of magic was that it was a multiracial different racial groups in social life or at school. currently airing. And, since my visit, a regular college. I had visited South Africa once before, They wouldn’t be able to travel on public Monday Night Magic show has started in in the 1980s at the age of 11. -

4 Comedian of the Month Long John 72 Cape Town Comedy Festifal 77 One Man Show Review Human Behavior

1 2 CONTENTS MAGAZINE 4 Comedian of the Month Long John 72 Cape Town Comedy Festifal 77 One man Show Review Human behavior Message from the Editor Kraai Du Toit If you enjoy the Magazine and you want to give feed- back please mail us at :sa- comedianmagazine@gmail. com If you have any complaints Please mail them to : IAMASTUPIDPERSON@Dum- bass.com We are doing this maga- zine Free of Charge , so if you like the magazine and podcast please feel free to make a donation to keep this project alive. 3 4 Comedian of the month Comedian of the month Long John Comedy is panning out for Long John 2019 SAVANNA Pan African Comic of the Year Long John is an Multi Award Winning International Comedian from Zimbabwe, and standing at over 6 feet, his comedy journey continues to stretch over the African Continent and beyond. He was laughed at for being tall, dark and handsome squint; however, his humor has been able to bringvlaughs to thousands of people, whilst keeping an eye on the rest of the world. Literally and Figuratively! His comedy is brought to life by past experiences, observations and his view (from the top) which elicit rib-tickling laughs, regardless of the crowd. Since making his comedy debut in 2012, he has since performed with and alongside the biggest names on the African Continent, which include, SA’s favorite Uncle, Barry Hilton Loyiso Gola Kanssime Anne Riaad Moosa, Basket Mouth And many more You may have found other comics funny but you will be laughing LONG after witnessing the very funny, Long John. -

National Arts Festival Programme

DEPARTMENT OF SPORT, RECREATION, ARTS AND CULTURE Private Bag/Ingxowa Eyodwa/Privaatsak X0020, BHISHO 5605 The Department Our Programmes The Department of Sport, Recreation, Arts and The programmes of the Department are Culture gives due regard to provincial priorities designed to render services in the following by ensuring that its mission caters sufficiently areas: for youth, women, the disadvantaged and ; Sport and Recreation the disabled. The guiding principles for ; Arts and Culture programme development are based on the 10- ; Libraries and Information Services year Provincial Growth and Development Plan. ; Museums and Heritage Our Vision A united, active, and winning province Contact details: through sport, recreation, arts and culture MEC Mrs Xoliswa Tom Member of the Executive Council: Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture Our Mission Tel: 043 – 604 4101 To develop and promote Sport, Recreation, Fax: 043 – 604 4093 Arts and Culture for spiritual, intellectual, physical and material upliftment of the people of the Eastern Cape Mr Mzolisi Matutu Head of Department: Our Values Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture ; Unity of purpose Tel: 043 – 604 4019/20 ; Respect for self and others Fax: 043 – 642 5309 ; Commitment to service delivery ; Loyalty to the organisation and the people we serve ; Work ethics Ms Naledi Nkula ; Honesty General Manager: Cultural Affairs ; Communication Tel. 043 – 604 4013 ; Equity Fax. 043 – 642 5386 SISONKE SINAKHO 2 CONTENTS 4 Festival Messages 6 Acknowledgements 8 Index 12 Standard Bank Young Artist Award -

The Street Was Quiet, No Cars, No Children on Bicycles

Chapter 12 The time that David had spent in Britain had been good for him, but now that he was back in South Africa, he saw his homeland through new eyes. He was amazed at what lay in front of him. Here was rich material to fuel his songwriting. He was brimming with creativity. Everywhere he looked he saw or experienced something which inspired him. He began penning songs from a South African perspective. No more lyrics about the streets of London, or being down on his luck in Louisiana. David was no longer interested in writing and performing music that tried to emulate the American and British experiences. Instead, he threw himself into the vibrant tapestry of his South African lifestyle, the good and the bad. Songs such as “Bellville Blues”, “Signal Hill”, and so on, flowed from David’s pen. This new direction in David’s songwriting gave him the ammunition to talk about the life he was intimately familiar with, along with the possibility to speak of and for the unheard, the invisible everyday person of the South African platteland. A song such as “Montagu” was rooted in a place he knew, geographically and culturally. In this song he refers to the muscatel from the area, he speaks of the habit of the rural people often being curious about one’s family roots – who one is related to by birth or marriage. He also mentions the ubiquitous café found on the corner with its Coca Cola or Springbok tobacco advertising painted on the walls. In these songs David could mix a certain amount of romanticism in his subjects and temper it with political realism. -

POST-DOCTORAL FELLOWSHIP in Partnership With

POST-DOCTORAL FELLOWSHIP In Partnership with 1 Message from NIHSS he National Institute for the Humanities Academic leader, with more flexibility in terms of and Social Sciences (NIHSS) in collaboration the direction of your research. The invaluable skills Twith South African Universities; initiated and experience gained as a postdoc can be key the Postdoctoral Research Capacity Building to future applications to tenure-track positions. Programme as an opportunity to advance further This PDRF programme will advance knowledge research and contributing to the changing epistemologies in the humanities and the social landscape within the Broader Humanities and Social sciences. Sciences field. Our implementation model for the Postdoctoral The Postdoctoral Research Fellows (PDRFs) programme, is to work with research centres within constitute South African citizens, with priority given universities, where our postdoc fellows could work to individuals who are NIHSS doctoral scholarship collaboratively in a structured environment. alumni. The main goal of a postdoctoral fellowship This flagship programme is a commitment on our is to develop professional and academic skills focus and priority to continue to serve and support while still under the mentorship of an experienced the Humanities and Social Sciences Community! 3 DR JOSEPH MAKANDA (UJ) [email protected] r Joseph Makanda is an upcoming Scholarship, UKZN, Joseph is also a member of the of four million migrants in South Africa. Most of the professional and social sciences scholar South African Association of Political Studies (SAAPS). migrants are spatially concentrated in three major Dwith a keen interest in conflict analysis, cities in South Africa – Johannesburg, Cape Town and peacebuilding, conflict transformation, post-conflict SYNOPSIS OF RESEARCH: Durban. -

When Granny Went on the Internet: the Screenplay and the Search for Content and Tone in South African Screenwriting

When Granny Went on the Internet: The Screenplay and the Search for Content and Tone in South African Screenwriting by Carolyn Burnett Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree PhD in Media and Digital Arts in the Graduate Programme in the College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. August, 2014 ABSTRACT The development of content and the creation of tone in a screenplay is a challenging task for the screenwriter. This thesis explores, through the writing of an original screenplay, how content is sourced and tone is manipulated in a comic story. The context of screenwriting in South Africa is established and an account is given of the emerging micro-budget filmmaking movement along with a discussion of issues relating to the broadband streaming of films in South Africa. Such factors, along with declining or stagnating cinema attendance, affect how films will be viewed and distributed in South Africa. A major case study was conducted on the South African film Jozi (2010) by director-screenwriter Craig Freimond. The influences, screenwriting process, sources of content and creation of tone in his film are examined through in- depth interviews and structural, thematic and tonal analysis of his work. An original feature-length screenplay, When Granny Went on the Internet (2013), was written. An account is offered of how the content was derived and tone was manipulated. A reflective report of the screenwriting process offers insight into the development of the multi-layered, tonally complex comic screenplay and suggests that a new form of South African comedy may be emerging.