Textualize Our Role As Information Maintainers in the Stewardship of Born-Digital Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELA 8Th Grade Week 3 (4/27 – 5/1) Clemens &

ELA 8th Grade Week 3 (4/27 – 5/1) Clemens & Gay Name: _____________________________ Context Clues 2.2 Directions: read each sentence and determine the meaning of the word using cross sentence clues or your prior knowledge. Then, explain what clues in the sentence helped you determine the word meaning. 1. Degrade: Suzie’s mother taught her to never let anyone degrade her, so now she demands respect in all of her relationships. Definition: ___________________________________________________________________________ What clues in the sentence lead you to your definition? 2. Frivolous: My mom wanted to get the red napkins for the party and my dad wanted the blue napkins, but I’m not even concerned about such frivolous things. Definition: ___________________________________________________________________________ What clues in the sentence lead you to your definition? 3. Discontent: If we use the red napkins, my mom will be happy but my dad will be discontent. Definition: ___________________________________________________________________________ What clues in the sentence lead you to your definition? 4. Morsel: The dogs were so hungry that they would have killed one another for a morsel of meat. Definition: ___________________________________________________________________________ What clues in the sentence lead you to your definition? 5. Fretful: My mom always worries about my grades and the colleges that I’ll be able to attend, but if she were a little less fretful she’d be a lot more fun. Definition: ___________________________________________________________________________ What clues in the sentence lead you to your definition? 6. Appall: John had seen horror movies before, but when he saw Bloodcore 6, he was so appalled by the bloodshed that he wrote the newspapers warning parents not to allow their children to see this movie. -

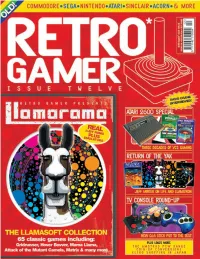

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

What Factors Led to the Collapse of the North American Video Games Industry in 1983?

IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk What factors led to the collapse of the North American video games industry in 1983? Image from http://cdn.slashgear.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/atari-sq.jpg “Atari was one of the great rides…it was one of the greatest business educations in the history of the universe.”1 Manny Gerard (former Vice-President of Warner) International Baccalaureate History Internal Assessment Word count: 1,999 International School of Toulouse 1 Kent, Steven L., (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, Calif.: Prima, (ISBN: 0761536434), pp. 102 Niall Rutherford Page 1 IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk Contents 3 Plan of the Investigation 4 Summary of Evidence 6 Evaluation of Sources 8 Analysis 10 Conclusion 11 List of Sources 12 Appendices Niall Rutherford Page 2 IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk Plan of the Investigation This investigation will assess the factors that led to the North American video game industry crash in 1983. I chose this topic due to my personal enthusiasm for video games and the immense importance of the crash in video game history: without Atari’s downfall, Nintendo would never have been successful worldwide and gaming may never have recovered. In addition, the mistakes of the biggest contemporary competitors (especially Atari) are relevant today when discussing the future avoidance of such a disaster. I have evaluated the two key interpretations of the crash in my analysis: namely, the notion that Atari and Warner were almost entirely to blame for the crash and the counterargument that external factors such as Activision and Commodore had the bigger impact. -

Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow

San Francisco, California August 20-21, 2005 $5.00 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow .... eight years! It's truly amazing to think that we 've been doing this show, and trying to come up with a fresh introduction for this program, for eight years now. Many things have changed over the years - not the least of which has been ourselves. Eight years ago John was a cable splicer for the New York phone company, which was then called NYNEX, and was happily and peacefully married to his wife Beverly who had no idea what she was in for over the next eight years. Today, John's still married to Beverly though not quite as peacefully with the addition of two sons to his family. He's also in a supervisory position with Verizon - the new New York phone company. At the time of our first show, Sean was seven years into a thirteen-year stint with a convenience store he owned in Chicago. He was married to Melissa and they had two daughters. Eight years later, Sean has sold the convenience store and opened a videogame store - something of a life-long dream (or was that a nightmare?) Sean 's family has doubled in size and now consists of fou r daughters. Joe and Liz have probably had the fewest changes in their lives over the years but that's about to change . Joe has been working for a firm that manages and maintains database software for pharmaceutical companies for the past twenty-some years. While there haven 't been any additions to their family, Joe is about to leave his job and pursue his dream of owning his own business - and what would be more appropriate than a videogame store for someone who's life has been devoted to collecting both the games themselves and information about them for at least as many years? Despite these changes in our lives we once again find ourselves gathering to pay tribute to an industry for which our admiration will never change . -

New Joysticks Available for Your Atari 2600

May Your Holiday Season Be a Classic One Classic Gamer Magazine Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 3 The Xonox List 27 Teach Your Children Well 28 Games of Blame 29 Mit’s Revenge 31 The Odyssey Challenger Series 34 Interview With Bob Rosha 38 Atari Arcade Hits Review 41 Jaguar: Straight From the Cat’s 43 Mouth 6 Homebrew Review 44 24 Dear Santa 46 CGM Online Reset 5 22 So, what’s Happening with CGM Newswire 6 our website? Upcoming Releases 8 In the coming months we’ll Book Review: The First Quarter 9 be expanding our web pres- Classic Ad: “Fonz” from 1976 10 ence with more articles, games and classic gaming merchan- Lost Arcade Classic: Guzzler 11 dise. Right now we’re even The Games We Love to Hate 12 shilling Classic Gamer Maga- zine merchandise such as The X-Games 14 t-shirts and coffee mugs. Are These Games Unplayable? 16 So be sure to check online with us for all the latest and My Favorite Hedgehog 18 greatest in classic gaming news Ode to Arcade Art 20 and fun. Roland’s Rat Race for the C-64 22 www.classicgamer.com Survival Island 24 Head ‘em Off at the Past 48 Classic Ad: “K.C. Munchkin” 1982 49 My .025 50 Make it So, Mr. Borf! Dragon’s Lair 52 and Space Ace DVD Review How I Tapped Out on Tapper 54 Classifieds 55 Poetry Contest Winners 55 CVG 101: What I Learned Over 56 Summer Vacation Atari’s Misplays and Bogey’s 58 46 Deep Thaw 62 38 Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 4 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to Issue 5 repeat it” - George Santayana December 2000 Editor-in-Chief “Unfortunately, those of us who do remember the past are Chris Cavanaugh condemned to repeat it with them." - unaccredited [email protected] Managing Editor -Box, Dreamcast, Play- and the X-Box? Well, much to Sarah Thomas [email protected] Station, PlayStation 2, the chagrin of Microsoft bashers Gamecube, Nintendo 64, everywhere, there is one rule of Contributing Writers Indrema, Nuon, Game business that should never be X Mark Androvich Boy Advance, and the home forgotten: Never bet against Bill. -

Sidedoor S4 E2 Atari Game Transcript

[INTRO MUSIC] Lizzie Peabody: This is Sidedoor, a podcast from the Smithsonian with support from PRX. I’m Lizzie Peabody. Howard Scott Warshaw: I'm part of a crowd of some 4 or 500 people, waiting to get into a dump. Lizzie Peabody: This is Howard Scott Warshaw. And on April 26, 2014, he was part of an unusual scene. Something like a wildly out-of-place tailgate party. People lined up with folding chairs, sun hats, beverages… in the middle of the New Mexico desert. Howard Scott Warshaw: It was a hot day. I mean, it was hot, but there was no dessert. It was just desert. Lizzie Peabody: Oh yeah, Howard has real thing for puns. Howard Scott Warshaw: And they open up and here we go. And we're all rushing into the dump and there's a lot of excitement. You know, we're on a mission to uncover, uh, the truth or not of a very popular urban myth. Lizzie Peabody: The legend goes like this: Once upon a time, in a land called Silicon Valley, an American tech company invented video games that enchanted children and brought billions of dollars flowing through its doors. The company was called Atari. Atari made many good games, until one day, in 1982, it made a bad one. A really bad one. A game so bad it has been called “the worst video game of all time.” Lizzie Peabody: The video game was, “E.T.: The Extraterrestrial.” According to the myth, it was so bad, it put Atari out of business. -

Final Exam /Revision Sheet AY (2019 – 2020) Grade 10/Girls Name: ______Section: ______

ENGLISH REVISION SHEET First TERM/ Final Exam /Revision Sheet AY (2019 – 2020) Grade 10/Girls Name: _________________________ Section: ________________ Teacher: ________________ Date: ___________________ Part A: Comprehension Q1- Read the following text then answer the questions below. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial is a video game that came out for the Atari 2600 game system in 1982. It was based on a very popular film of the same name. It cost over 125 million dollars to make. Star programmer Howard Scott Warshaw created it with consultation from Steven Spielberg. And it is widely considered to be one of the worst video games ever created. The massive failure of E.T. and its effects on Atari is an often-mentioned reason for the video game industry crash of 1983. It was July 27th, 1982. Howard Scott Warshaw was hot off the success of his most recent game, Raiders of the Lost Ark. He received a call from Atari C.E.O. Ray Kassar. Atari had bought the rights to make a video game version of Spielberg's movie, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which had just been released in June. Kassar told Warshaw that Spielberg had specifically asked for Warshaw to make the game. Warshaw was honored, but there was one huge problem. Atari needed the game finished by September 1st in order to start selling it during the Christmas season. It had taken Warshaw six months to create Raiders of the Lost Ark. The game he made prior to that took him seven months. He was expected to create E.T. -

Power Hour Lessons MS-HS

Power Hour Lessons MS-HS POWER HOUR RECHARGED FOR THE 21ST CENTURY LESSON GUIDE: HIGH SCHOOL POWER HOUR RECHARGED FOR THE 21ST CENTURY LESSON GUIDE: HIGH SCHOOL © Copyrighted Material. Important Guidelines for Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to photocopy all pages of this guide that are required for use by Boys & Girls Club staff members. Only the original manual purchaser/owner may make such photocopies. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis multiple copies of ma- terial reproduced from this publication. Copyright © 2016 Boys & Girls Clubs of America All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record- ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher. Boys & Girls Clubs of America 1275 Peachtree St. NE Atlanta, GA 30309-3506 404-487-5700 | www.bgca.org Table of Contents Introduction 5 Program Overview 6 The Power Hour Lesson Guide 7 Facilitating the Lessons 9 General Tutoring Guidelines 11 Common Core State Standards High School: Reading Lessons 27 Identifying Text Evidence 34 Determining the Main Idea 39 Analyzing Directions and Following Precise Steps 46 Determining the Meaning of Words and Phrases 51 Determining the Text Structure 58 Understanding Point-of-view 59 Point-of-view Sentences 64 Presenting Topics in Visual Form 69 -

This Is the Story of the Death of Atari. Some Would Argue

This is the story of the death of Atari. Some would argue that Atari died when Nolan Bushnell left the company in 1978, but to me the real death of Atari began in the 4th quarter of 1982. Atari was founded in 1972 by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney as Syzergy Co. They later realized that name had been used and changed it to Atari, a term taken from the game Go roughly meaning “you are about to be taken” which oddly enough was prescient about the future of Atari. Their first big success was Pong in November of 1972. Further arcade games followed until a project then code named Stella was completed and renamed the Atari VCS or as most would know it today, the Atari 2600. There was one problem: the leadership of Atari were not business oriented. They were dreamers, engineers, and programmers that were ill-equipped to handle the business Atari had grown into. Atari did not have the capital or expertise to successfully bring the VCS to market. Enter Warner Communications who purchased Atari in 1976. Warner then installed the more business-oriented Ray Kassar to oversee Atari and Bring the VCS to market. The VCS was released in November of 1977 and grew into a phenomenon that would come to not only give rise to a new industry, but also install itself as a mental fixture synonymous with the words video game for a generation. From 1978 through early 1982 Atari saw massive success and growth fueled by the VCS and various arcade hits. -

Comprehension : a Test of Your Ability to Read a Piece of Text and Answer Questions About It

Year 8 English Exam Revision Notes The Year 8 English exam will consist of four parts: Comprehension : A test of your ability to read a piece of text and answer questions about it. Revision advice: Read attached passage on the E.T. game and then work through comprehension questions attached. This should familiarise you with comprehension skills and the exam format. Vocabulary: A test of some of the relevant vocabulary that we have learned this year. Revision advice: Make sure you know the vocabulary we have been learning this year. The extended list of words from which the exam words will be taken is attached. Text Response: An extended answer on a question about The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Revision advice: Complete Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Common Assessment Task, pay special attention to using evidence from the text to support your answer and then attempting some analysis of this evidence. Additionally, short practise questions can be found at the end of this revision booklet. Creative Narrative: Write a story based on a prompt. Revision advice: Practice writing dialogue correctly, make sure you understand that scene and characters are described. Practice writing very brief stories with the pattern of: introduction, conflict, rising action, climax, and resolution. Creative Narrative. Here are some writing prompts with which to complete a practice story: 1. Outside the Window: What’s the weather outside your window doing right now? If that’s not inspiring, what’s the weather like somewhere you wish you could be? 2. Unrequited Love: How do you feel when you love someone who does not love you back? 3. -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power.