Covenant So Simple| [Poems]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUFON UFO Journal

MUTUAL UFO NETWORK UFO JOURNAL OCTORFR 100R J NIIMRFR^AA $1 TAB EXONTENIS MUFON UFO Journal October 1998 Number 366 (USPS 002-970) (ISSN 0270-6822) Editor's brief: 103 Oldtowne Rd It is my pleasure to welcome Dick Hall back to the Journal as a regu- Seguin, TX;78155^4099 lar contributer. His column will be similar to one which he did when I '-' Tel: (830)379-9216 edited Skylook, the forerunner of the Journal, many years ago. Dick, of course, also edited the Journal just prior to Bob Pratt. He will provide, FAX (830) 372-9439 experience, insight, and balance which will serve our readers well. Editor: ? The Cover: Top: Crop formation at Littlebury Green, Essex, UK, July Dwight Connelly 1996. (280 ft. across) Bottom: Crop circle in wheat field at Alton Priors, 14026 Ridgelawn Road Wiltshire on July 11. 1997. (500 ft. across) ©Steve Alexander. Martinsville, IL 62442 V Tel: (217} 382-4502 Physics of crop formations by John A. Burke 3 e-mail: [email protected] What about creatures being reported? by Cynthia Luce 7 Editor in Chief: Mexico City video analysis by Jeff Sainio 9 r Walter H:Andrusi Jr. Filer's UFO reports by George Filer. 11 103OldtowneRoad Lasers and the 'Phoenix lights' by David Rapp 12 Seguin, TX 78155 Book Review: The Cash-Landrum UFO Incident 16 :&•• 830-379-9216 MUFON Forum 17 Perspectives by Richard Hall 18 Columnists: Calendar of upcoming events 20 Walter N. Webb Readers'Classified ads 21 "':.' Richard HalP '.V •• The Night Sky by Walter N. Webb 22 Director's Message by Walter Andrus 24 Art Director: Vince" Johnson MUFON's mission is the systematic collection and analysis of UFO data, with the ultimate goal of learning the origin and MUFON UFO Hotline: nature of the UFO phenomenon. -

Aliens on Earth. Are Reports of Close Encounters Correct?

Aliens on Earth. Are reports of close encounters correct? Pawel Sobkowicz pawelsobko@ gmail. com (Dated: April 1st, 2012) Popular culture (movies, SF literature) and witness accounts of close encounters with extrater- restrials provide a rather bizarre image of Aliens behavior on Earth. It is far from stereotypes of human space exploration. The reported Aliens are not missions of diplomats, scientists nor even invasion fleets; typical encounters are with lone ETs (or small groups), and involve curious behav- ior: abductions and experiments (often of sexual nature), cattle mutilations, localized killing and mixing in human society using various methods. Standard scientific explanations of these social memes point to influence of cultural artifacts (movies, literature) on social imagination, projection of our fears and observations of human society, and, in severe cases, psychic disorder of the involved individuals. In this work we propose an alternate explanation, claiming that the memes might be the result of observations of actual behavior of true Aliens, who, visiting Earth behave in a way that is then reproduced by such memes. The proposal would solve, in natural way, the Fermi paradox. I. EXISTENCE OF EXTRATERRESTRIAL based on increased ratio of planet detection based on mi- CIVILIZATIONS crolensing [9], puts this ratio at close to 1 (estimating number of planets as close to the number of stars in the A. Drake equation Galaxy). Applying this correction to Franck et al. esti- mates gives us much larger number of Earth-like planets The two major problems faced today by scientists in- – about 50 million. Discussing temporal aspects of the Drake equation, terested in extraterrestrial civilizations are: how many ´ such civilizations exist today or existed before in the Cirkovi´c[10], stresses the importance of the longevity Milky Way? Provided the positive answer to the first of civilizations. -

Delta Green the Role-Playing Game V.1.2

Delta Green The Role-Playing Game v.1.2 DELTA GREEN THE ROLE-PLAYING GAME ARC DREAM PUBLISHING PRESENTS DELTA GREEN: THE ROLE-PLAYING GAME BY DENNIS DETWILLER, ADAM SCOTT GLANCY, KENNETH HITE, SHANE IVEY & GREG STOLZE with GIL TREVIZO DEVELOPERS & EDITORS DENNIS DETWILLER & SHANE IVEY ART DIRECTOR & ILLUSTRATOR DENNIS DETWILLER GRAPHIC DESIGNER SIMEON COGSWELL COPY EDITOR LISA PADOL DELTA GREEN CREATED BY DENNIS DETWILLER, ADAM SCOTT GLANCY & JOHN TYNES “That cult would never die till the stars came right again, and the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth. The time would be easy to know, for then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and reveling in joy.” —H.P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu "On Edward Teller’s blackboard at Los Alamos I once saw a list of weapons—ideas for weapons —with their abilities and properties displayed. For the last one on the list, the largest, the method of delivery was listed as 'Backyard.' Since that particular design would kill everyone on Earth, there was no use carting it elsewhere." —Robert Serber, about Edward Teller “Blessed be the torch.” —Máximo Gómez AGENTS READ NO FURTHER !1 ©2016 The Delta Green Partnership Delta Green The Role-Playing Game v.1.2 THE FIRST REPORT When Chilton took his shot, I jumped into the mirror room with the laptop bag, thinking, anywhere is better than here. -

Ufo Research Evidence and Resources

UFO RESEARCH EVIDENCE AND RESOURCES Copyright © 2020 Ronald Olch Revision 12-18-20 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Five Good Reasons to Believe in UFOs ...................................................... 2 History of the search for intelligent life beyond Earth .................................. 6 The Best Evidence for existence of UFOs/UAPs and for continued study ... 9 UFO sightings at ICBM sites and Nuclear Weapons Storage Areas Including interference with missile launch systems ................................... 13 Large-scale studies of UFOs..................................................................... 14 Scientific Data Collection Efforts ............................................................... 16 UFO Classification Systems ...................................................................... 20 Size and Weight Estimates ....................................................................... 22 Statements about UFOs by Credible Individuals ....................................... 23 Recommended Books and Periodicals ..................................................... 31 Researchers by Primary Field of Interest and Publications ....................... 37 Cerology ("Crop Circles") Research .......................................................... 41 UFO-Related PhD and MS Degrees ......................................................... 43 Compilations of Evidence ........................................................................ -

To Believe Or Not to Believe the Crop Circle Phenomenon in the Netherlands Õ.Ì

To believe or not to believe The crop circle phenomenon in The Netherlands õ.ì Th eo Meder är iE ËiE In ¡hc Summe¡ of 2001, I srarted my rcserrch find ley lines rvith their clowsing rods or rneas- of n¿r¡atives colrcerning crop circles ancl their ure the energy with cheir pendulums, some possibly supenutural, clivine, ecologic,rl or come to meditate. l'atmers are sclclom pleased extraterrescrial origin. I wâ[ted to focus ol-r with clop circlcs because of the h¡rves¡ loss rh( râlcs Jnd c,rnrcptions ìrt u lrich clop cir- involved - c¿usecl not only by thc fìattening cles ale interpretcd ¡s non-rr¡n-macle signs of of the crop, but also by the trampling of curi- <(9 the time"^. Furthermore, rny ¡escr¡ch involved ous visito¡s. Sceptic scientists hardly bother to oq the concemporary cult movement ¡hat sc¿r¡tccl con-re, buc csoteric ¡ese¡rchers come to rnves- 9+{ with ufos in ¡he 1950s as a kincl of'proto- tigate, measure, sample, film and photograph, New ;\ge rnovernent'. 1 Crop circles u'e thc for later analysis rnd interpretation. Journalìsts 5i most tangible element of this mode¡n New r isir ¡he lormltion" cìuring rhc silly scrsc'n in Agc convicrion, which eìso incorporatcs ufo sealch of a juicy stor¡ preferably on the mys- sightings, alien rbductions, cattle mutilation, tery of the unexplaincd, on the subject of licde govcrûment cover-ups, free energy, lcy Iines, grecn mqn. or un thË l¡ct thct thc cntire cr,'p mysterious orbs of light, alte¡native ¡heories on circle phenonenon is a huge man-macle ¡rracci ¡hc c¡e¿tion of man, conneccior-rs with ancient cal jokc.2 ancl prehistoric Íronuments (like tÌre Ììgyptian pymnids ¿nd Cel¡ic Stonehcngc), thc cosmìc Englancl: where the knowledge of lost civilizations (Adar.rtis, ìVlayas phenomenon stârted a likc othe¡- etc.), and the expectations of rhe coming of Although some people to believe I new crâ or cven ¡n Encl of l)ays. -

Cattle Mutilations: an Episode of Collective Delusion

Cattle Mutilations: An Episode of Collective Delusion James R. Stewart During the late summer and early fall of 1974 the areas of northeastern Nebraska and eastern South Dakota experienced a rash of "cattle mutila- tions. " In most instances dead cattle were discovered with parts of their anatomy missing. The parts of the body most frequently mutilated were the sex organs, ears, and the mouth. The episode reached its zenith during early October when discoveries of mutilated cattle were being re- ported on a daily basis to law-enforcement officials throughout the area. It subsided almost as quickly as it had begun, and although other areas of the country have subsequently reported the same phenomenon, there has been no media coverage of any further mutilations in this area. The cause of the mutilations was, and in fact still is, controversial. Some persons believed that it was the work of members of a Satan-wor- shipping cult whose ceremonies called for the blood and parts of animals. Others believed that the mutilations were the work of extraterrestrial be- ings whose purpose was to examine the physiological makeup of cattle, or simply to terrorize human beings. Still others felt that the mutilations were the work of small predators who, after having discovered the carcasses of already dead animals, proceeded to eat the accessible parts. What follows is a detailed account of the outbreak, culmination, and precipitous de- cline of the cattle-mutilation episode. The episode The mutilation episode was apparently triggered by the more-or-less si- multaneous reports of a cattle mutilation and the alleged sightings of UFOs and a "monster-thing" in the area. -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25 -

The Ufo Enigma 21R2 Oirs Crscir2 Crs Crsoirs

CR C S UG 633 76-52 SP THE UFO ENIGMA 21R2 OIRS CRSCIR2 CRS CRSOIRS MAR CIA S. SMITH Analyst in Science and Technology Science Policy Research Division March 9, 1976 CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CR _ t' TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 What is a UFO? 2 A. Definitions 2 B. Drawings by Witnesses 5 C. Types of Encounters 10 II. Witness Credibility 15 A. Sociological and Psychological Factors 15 B. Other Limitations on Witnesses 21 C. Strangeness-Probability Curve 24 III. Point - Counterpoint 25 A. Probable Invalidity of the Extraterrestrial Hypothesis 26 B. Alleged Air Force Secrecy and Cover Ups 29 C. Hoaxes and Witness Credibility 31 D. Possible Benefits to Science From a UFO Study 34 IV. Pre-1947 Accounts 37 A. Biblical Sightings 37 B. Other Early Reports 38 C. The Wave of 1896 41 D. The Post-War European Wave 44 V. 1947-1969 Accounts and Activities 46 A. United States 46 1. Kenneth Arnold and the 1947 Wave 46 2. U. S. Air Force Involvement (1948-1969) 48 a. Projects Sign and Grudge (1948-1952) 49 b. The Robertson Panel and Project Blue Book (1952-1953) 53 c. Special Report #14 and the O'Brien Report: Project Blue Book (1953-1966) 56 d. The Condon Report and Termination of USAF Interest (1967-1969) 63 3. Congressional Interest 69 a. House Armed Services Committee Hearings (1966) 69 b. House Science and Astronautics Committee Hearings (1968) 72 4. Private Organizations 80 a. APRO 81 b. NICAP 82 c. CUFOS 83 d. MUFON 84 e. -

Ambiguous Intrusions: the Ufo / Alien Encounter Phenomenon and the Politics of Repression

AMBIGUOUS INTRUSIONS: THE UFO / ALIEN ENCOUNTER PHENOMENON AND THE POLITICS OF REPRESSION By NIGEL D’SA Integrated Studies Final Project Essay (MAIS 700) submitted to Dr. Paul Kellogg in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta April, 2014 ii Abstract Despite a growing body of scholarly and scientific literature, the topic of UFOs (Unidentified Flying Objects) – and the related question of alien encounters – still elicits profound scepticism, dismissal, and ridicule within the academic community and the sciences. This reaction is indicative of a ‘UFO taboo’ – a concerted effort to marginalize and suppress recognition of the UFO. The UFO taboo operates in society as an ‘epistemology of ignorance’ that relegates the subject to the realm of science fiction, tabloid journalism, fringe theories and collective cultural fantasy. A literature review of the leading scholarly work on the subject will serve both to contextualize the history of the UFO problem, and counter the inviolability of the taboo. This paper will outline some disciplinary perspectives beginning with an examination of the political theory behind the taboo. The school of Transpersonal Psychology, the pioneering work of John E. Mack, and a parallel approach in Anthropology will help us conceptualize the most controversial aspect of the phenomenon: the alien abduction experience. The paper concludes with a summary of the major explanatory hypotheses for UFOs and abductions, and points to the need for an international interdisciplinary research project. This paper makes no attempt to solve the UFO problem. But by asking what the UFO – through its insistent presence and our strange apathy towards its presence – can tell us about our world, our systems of knowledge, and our systems of rule, the paper argues for the importance of the phenomenon and the onus that is placed on science and the academy to legitimate its study and contribute to our understanding of it. -

{TEXTBOOK} Messengers of Deception: UFO Contacts and Cults Ebook, Epub

MESSENGERS OF DECEPTION: UFO CONTACTS AND CULTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacques Vallee | 288 pages | 30 Jun 2008 | Daily Grail Publishing | 9780975720042 | English | United States Messengers of Deception: UFO Contacts and Cults - Jacques Vallee - Google Books The man standing at the left is the main witness,patrolman Lonnie Zamora. Photo courtesy of United Press I nternational. For the world of the comingdecades, the key symbol may well be a shining disk from heaven. Many people around us today are preparing to greet it with delight,even if that means falling under the control of forces they do notunderstand. These people are the UFO contactees and the believersin celestial visitation, the followers of the saucer prophets. They canpave the way for dramatic changes. It is a common mistake to assume that contactees are alwaysirresponsible crackpots or elderly mystics. A case in point is ayoung man named Gregory, whom I used to know as a systemsprogrammer with one of ou r lead ing "think tanks. He is now publishing a newsletter devotedto his experiences with higher entities; he believes that, in so doing,he follows the telepathic instructions of a superior force. Some feelthat he has found a new moral framework based on revelation. Others argue that he is the victim of a delusion that could spread In either case, the implications are serious. It is notbecause of their numbers or because of their leaders thirst for powerthat the followers of such sects will be especially influential. Ourinstitutions are vulnerable to the spreading belief in the irrational. People like Gregory do offer us a new dream, but it is so far fromreality that it could easily turn into a complete fantasy. -

Skeptics UFO Newsletter -2- March 2000

KEPTICS UFO NEWSLETTER SUN #62 SBy Philip J. Klass 404 'N" S! SW Wash1ngton DC 20024 March 2000 Copyright 2000 1970s Data Helps Identify January 5th Illinois UFO As Extraterrestrial •The UFO Handbook; authored 21 years ago by Allan Hendry--then director of the Hynek Center for UFO Studies (CUFOS)- -provides valuable insights to explain UFO sightings by multiple witnesses during the pre-dawn hours of Jan. S, 2000, in west-central Illinois. UFOiogists and the news media were especially impressed because of the unusual descriptions of the UFO and because several of the witnesses were small-town law enforcement officers. Hendry's book reports the results of his investigation of 1,307 UFO reports submitted to CUFOS- -many of them by law enforcement officers. Hendry discovered that 360 of these UFOs- -nearly 28% of ALL the UFO !ightin_u~ort~d to CUFOS- -turned out to be bright planets and stars, as highlighted in Chapter 2, titled: •The UFO Imposters: Nocturnal Light IFOs (identified flying objects). • In a later chapter Hendry analyzed the professional backgrounds of those who had submitted UFO reports that turned out to be IFOs. Law enforcement officers had the worst record: 94% of their UFOs turned out to be IFOs. BRIGHT CELESTIAL BODIES GENERATE WIDE VARIETY OF UFO DESCRIPTIONS One of the characteristics of UFO reports generated by bright planets/ stars, Hendry learned, is the "large variety of shapes reported." Also a variety of colors: "Starlight can be refracted into a rapid sequence of colors. Red, white, and blue are the most common.... The effect is especially prominent when the planets /stars are near the horizon." (Emphasis added.) Hendry als~ cautioned about the autokinesis effect: "If one stares intently at a star in the dark without a frame of reference, it can appear to 'wander' about in the sky.. -

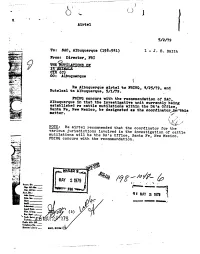

Animal Mutilation Part 5 of 5

___________.-_..._.-_.-.- -~~--i" " " ! . , _ .., ~ . '2 <. ' J J E ' 1' Airtel - I _ 7 - . '="r-"' ">'.vI _./' -. '_ .'-:'" "' .n'L,. ., 5/2/79 '-La. ' j ___,-..._.'- . _ ' . 5 ' .'.2,,;=-- . .. 591;,,-;- . To: sac, uuuquerque 98-5&1! 1 e- J. E. Smith " -eca ._~ Fromi oi:-eater, re: ' . ",1 -.-¢- %~¢~ 'me%1'riLA' ens ' /_ . , ---._r_ ._ 3.;-._J_, i_--'_; ,3}, ¢- - 1-. 'i5ZIiiI£§;I""Qz '-4¢'l':":"_ Egerm cm G!.. 1-=2-:-5" O0: Albuquerque 1--v_ " i 92. _ Re Albuquerque uirtel to FBIHQ, l/E5/79, and r Butelcal to Albuquerque, 5/l/79. - FBIHQ concurs uith the recommendation or Snc, F;-.. Albuquerque in that the investigative unit currently being eetebliehed re cattle mutilation: within the DA: orriee Se nt e P e, New Mexico, be designated an the eoordinetor,in*thie matter. 1 ' If I , 4- . s . W I .r 4 - - .__&;_L_ ,1 4. rs, ¢ NOTE: Re airtel recommended that the coordinator for the various jurisdictions involved in the investigation of cattle mutilations will be th D e A 's Office, Santa Fe, New Mexico. nu.- FBIHQ concurs with the recommendation. .1!- 92' .. -. ,_...r.. __,_.. _._ _ -:- PE. / E -2 r " we '*~~-:-Q0 /7 5 -I /4 /P _.é v? Ameuu___ MAY - 2197 " ?f-n_.;_;_Q__-Q I ,_ . _, _e :Z:§::III ~e"" FBl*Hvwu- ' -i- [V .