Invisible Dread, from Twisted: the Dreadlock Chronicles Bertram D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Science-Based Guide to Afro-Textured Hair Care from Nylah’S Naturals

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A Science-Based Guide to Afro-Textured Hair Care from Nylah’s Naturals. This vegan hair care brand shares their top five tips on how to care for Black hair. Afro-textured hair requires special care, as the hair unique structure is prone to extra dryness and therefore are more fragile and susceptible to breakage. Kam Davis, Founder and CEO of Nylah’s Naturals, shares some expert advice on how to care for Black hair. Since ancient times, afro-textured hair has been an integral part of Black culture. From the Ancient Nile Valley civilizations to the establishment of Western African empires, hair has maintained a spiritual, social, cultural and aesthetic significance in the lives of African people. It was a part of a person’s social and cultural identity, signifying personal status. Unfortunately, in recent centuries, Black women and men were forced to follow the standards of beauty industries that did not accept natural afro-textured hair, forcing many to chemically straighten their hair or wear wigs. Encouragingly, over the past few years, the tendency started shifting in a different FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE direction, with natural afro-textured hair being more and more widely accepted, celebrating its curly nature and uniqueness. “At Nylah’s Naturals, we realize that our mission goes way beyond creating natural, high-quality products catering to afro-textured hair. For so many years Black women were fighting the very nature of their hair, so now we feel there is a need to educate and share the best practices on how to care for Black hair in such a way that it highlights its health and beauty,” - shares Kam Davis, Nylah’s Naturals CEO and Founder. -

AFRO-AMERICAN ART the METROPOLITAN MUSEUM of ART Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art

<^ ? AFRO-AMERICAN ART THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art June 19-August 1,1976 Catalogue by Regenia A. Perry The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ON THE COVER: Ashur Moses Nathan and Son by Jules Lion. Pastel on canvas, ca. 1845. Lent by Francois Mignon, Natchitoches, Louisiana. Pho tograph by Don R. Sepulvado, Natchitoches, Louisiana. Copyright © 1976 by The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1 he Metropolitan Museum is pleased to present the ex hibition Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art as part of our observance of the nation's Bicentennial celebration. We are grateful for the generosity of the lenders, whose cooperation made the exhibition possible, and we congratulate Dr. Regenia A. Perry, who or ganized the show. It is fitting at this time not only to ex amine this important aspect of our national heritage but to view it in the broader context of the history of Ameri can art as represented in the collection of The Metropoli tan Museum of Art. THOMAS HOVING Director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the School of the Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University for granting me a leave of ab sence to work on this project during the academic year 1975—1976, to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for funding the fellowship at The Metropolitan Museum of Art which I received during this year, to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for working with me in present ing this exhibition, and to the numerous institutions and private col lectors who have generously lent their works. -

Wigmaker and Barber by Sharon Fabian

Name Date Wigmaker and Barber By Sharon Fabian Cosmetology is a popular vocational subject in high school. In cosmetology class, students learn to wash and cut hair. They learn to give perms and to color hair too. They learn how to do a fancy hairstyle for a special occasion like a prom. They might learn to cut and style wigs as well as real hair. Cosmetology students often go on to work as hairdressers, styling hair for customers. In colonial times, there were also people who worked as hairdressers. Some people are surprised to learn that, because we often think of the colonists as hard working people who didn't have time for frivolous things like a fancy hairdo. However, there were many people in colonial America who were very fashion conscious and who kept up with the latest styles in both clothing and hairstyles. This was especially true in the larger cities like Williamsburg, Virginia. A city like Williamsburg had shops that catered to the fashion conscious. Wigmakers and barbers there both provided hairdressing services. A barber might provide shaves and haircuts in addition to his other duties, such as performing surgery and pulling teeth! A wigmaker, of course, made wigs, and in the 1700s, wigs were the latest fashion! The fashion of wearing wigs began with the royalty in France; it spread to England and then to America. In colonial times, the gentlemen, not the ladies, wore wigs. Colonial gentlemen also wore queues. A queue was like a ponytail wig that was tied on at the back of the head. -

An End to “Long-Haired Freaky People Need Not Apply”?

“Signs” of the Times: An End to “Long-Haired Freaky People Need Not Apply”? Sean C. Pierce Harbuck Keith & Holmes LLC Coming on the heels of United Parcel Service, Inc.’s seminal case on pregnancy discrimination, Young v. United Parcel Service, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 1338 (2015), the world’s largest package delivery company was recently also ensnared in a religious discrimination claim. UPS agreed to pay $4.9 million and provide other relief to settle a class-action religious discrimination lawsuit filed by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The suit was resolved with a five-year consent decree entered in Eastern District of New York on December 21, 2018. EEOC v. United Parcel Service, Inc., Civil Action No. 1:15-cv-04141. The EEOC alleged UPS prohibited male employees in supervisory or customer-contact positions, including delivery drivers, from wearing beards or growing their hair below collar length. The EEOC also alleged that UPS failed to hire or promote individuals whose religious practices conflict with its appearance policy and failed to provide religious accommodations to its appearance policy at facilities throughout the U.S. The EEOC further alleged that UPS segregated employees who maintained beards or long hair in accordance with their religious beliefs into non-supervisory, back-of-the- facility positions without customer contact. These claims fell within the EEOC’s animosity to employer inflexibility as to religious “dress and grooming” practices, examples of which include wearing religious clothing or articles (e.g., a Muslim hijab (headscarf), a Sikh turban, or a Christian cross); observing a religious prohibition against wearing certain garments (e.g., a Muslim, Pentecostal Christian, or Orthodox Jewish woman’s practice of not wearing pants or short skirts), or adhering to shaving or hair length observances (e.g., Sikh uncut hair and beard, Rastafarian dreadlocks, or Jewish peyes (sidelocks)). -

Barbershop Quartet Sc They Wear Even Politicians and Bureaucrats Are Serious About Their Hair: Nearly a Dozen It Well Federal Entities Have On-Site Barbers

Great HAIR OM SC EW N THEY WEAR EvenBarbershop politicians and bureaucrats are serious aboutQuartet their hair: Nearly a dozen IT WELL RIPPLAAR/SIPA/ federal entities have on-site barbers. Here’s a look at four. T Sure, Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt By Kate Parham TOFFER sported distinguished facial hair, but modern S RI K Washington men seem more comfortable with a Y B close shave—though there are exceptions. OLDER We asked Mike Gilman, cofounder of the House of Central H OM; Grooming Lounge, and Aaron Perlut, chairman of ➻ Representatives ➻ Intelligence SC EW the American Mustache Institute, to tell us who Agency N around town has winning facial hair. Barber: Joe Quattrone, formerly LLAN/ U a farmer in Italy, heads the House’s M Barber: Daivon Davis is not only c By Christine Ianzito M privatized barbershop. His is one of K the first African-American to own C the best jobs, he says, “because you the CIA’s barbershop but the first to ATRI P come in contact every day with the cut hair in the shop, which opened people who control the world.” LDING/ Ted Leonsis Jayson Werth in 1955. Now 24, he got the gig at age U 18, then bought the shop in 2010. ENTREPRENEUR NATIONALS OUTFIELDER Inside look: He has trimmed ev- Y CLINT SPA eryone from Prime Minister Giulio Inside look: Davis’s chair has seen B ER Andreotti of Italy—who insisted on the likes of General Michael Hayden Z having his picture taken with Quat- and former CIA director Leon I; BLIT ZZ trone—to Dick Cheney, Al Gore, and I Panetta. -

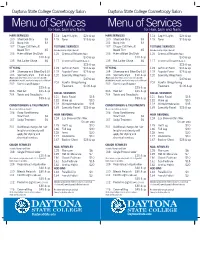

Menu of Services

Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Menu of Services Menu of Services for Hair, Skin and Nails for Hair, Skin and Nails HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) $10 & up $30 & up $10 & up $30 & up 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) _______________________________ $25 & up _______________________________ $25 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with $40 & up $40 & up detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) 203 Keratin Straightening 203 Keratin Straightening 202 Dominican -

Barber Shops Full Page

July/Aug 2012 Edition The Fayetteville Press Page 5b Community Barber Shops Flat Top Haircut Barbershop 360 Waves Brushing Techniques It is easy to achieve a flattop haircut, barbershop style As a guy who wants a perfect waved up hairstyle right from home. People are generally more familiar with you may want to consider 360 waves brushing tech- the flattops cousin hairstyle, the crew cut. The flattop is niques. To get those waves to spinning there is a certain similar to the crew cut in many ways, the difference is that way you need to handle your brush when stroking your with a flattop hairstyle the hair on the tops of the head is thirsty roots. A grooming plan that involves a strategic made to stand up, and is then cut in a flat style. This is what regiment of brushing is imperative to get your hair fol- gives this hairstyle is square shape. licles spinning. Some guys figure it out on there own but You would commonly find this hairstyle on boys. Girls others prefer a training guide. do sometimes wear this hairstyle or different variations or Are there tricks and trade secrets to getting these it, but this is uncommon. The flattop is a popular military style haircut because it is similar to the military crew cut. deep waves? Well yes and no. To get the effective and People commonly created this hairstyle with electric desired results you seek follow the instructions below clippers, which cut the sides and back of the hair. Using the provided by Wave Builder which includes their mainte- clippers, a stylist will cut the hair very close to the scalp; it nance preferences. -

Black Music of All Colors

SÉRIE ANTROPOLOGIA 145 BLACK MUSIC OF ALL COLORS. THE CONSTRUCTION OF BLACK ETHNICITY IN RITUAL AND POPULAR GENRES OF AFRO-BRAZILIAN MUSIC José Jorge de Carvalho Brasília 1993 Black Music of all colors. The construction of Black ethnicity in ritual and popular genres of Afro-Brazilian Music. José Jorge de Carvalho University of Brasília The aim of this essay is to present an overview of the charter of Afro-Brazilian identities, emphasizing their correlations with the main Afro-derived musical styles practised today in the country. Given the general scope of the work, I have chosen to sum up this complex mass of data in a few historical models. I am interested, above all, in establishing a contrast between the traditional models of identity of the Brazilian Black population and their musics with recent attempts, carried out by the various Black Movements, and expressed by popular, commercial musicians who formulate protests against that historical condition of poverty and unjustice, forging a new image of Afro- Brazilians, more explicit, both in political and in ideological terms. To focus such a vast ethnographic issue, I shall analyse the way these competing models of identity are shaped by the different song genres and singing styles used by Afro-Brazilians running through four centuries of social and cultural experience. In this connection, this study is also an attempt to explore theoretically the more abstract problems of understanding the efficacy of songs; in other words, how in mythopoetics, meaning and content are revealed in aesthetic symbolic structures which are able to mingle so powerfully verbal with non-verbal modes of communication. -

Symbolisms of Hair and Dreadlocks in the Boboshanti Order of Rastafari

…The Hairs of Your Head Are All Numbered: Symbolisms of Hair and Dreadlocks in the Boboshanti Order of Rastafari De-Valera N.Y.M. Botchway (PhD) [email protected] Department of History University of Cape Coast Ghana Abstract This article’s readings of Rastafari philosophy and culture through the optic of the Boboshanti (a Rastafari group) in relation to their hair – dreadlocks – tease out the symbolic representations of dreadlocks as connecting social communication, identity, subliminal protest and general resistance to oppression and racial discrimination, particularly among the Black race. By exploring hair symbolisms in connection with dreadlocks and how they shape an Afrocentric philosophical thought and movement for the Boboshanti, the article argues that hair can be historicised and theorised to elucidate the link between the physical and social bodies within the contexts of ideology and identity. Biodata De-Valera N.Y.M. Botchway, Associate Professor of History (Africa and the African Diaspora) at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, is interested in Black Religious and Cultural Nationalism(s), West Africa, Africans in Dispersion, African Indigenous Knowledge Systems, Sports (Boxing) in Ghana, Children in Popular Culture, World Civilizations, and Regionalism and Integration in Africa. He belongs to the Historical Society of Ghana. His publications include “Fela ‘The Black President’ as Grist to the Mill of the Black Power Movement in Africa” (Black Diaspora Review 2014), “Was it a Nine Days Wonder?: A Note on the Proselytisation Efforts of the Nation of Islam in Ghana, c. 1980s–2010,” in New Perspectives on the Nation of Islam (Routledge, 2017), Africa and the First World War: Remembrance, Memories and Representations after 100 Years (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018), and New Perspectives on African Childhood (Vernon Press 2019). -

WHO Surgical Site Infection Prevention Guidelines Web Appendix 7 Summary of a Systematic Review on the Effectiveness and Optimal Method of Hair Removal

WHO Surgical Site infection Prevention Guidelines Web Appendix 7 Summary of a systematic review on the effectiveness and optimal method of hair removal 1. Introduction Removal of hair from the intended site of surgical incision has traditionally been part of the routine preoperative preparation of patients undergoing surgery. Hair removal may be necessary to facilitate adequate exposure to the site and preoperative skin marking. Furthermore, suturing and the application of wound dressings can be complicated by the presence of hair. Apart from these practical issues, hair has been associated with a lack of cleanliness and the potential to cause surgical site infection (SSI). However, there is also the belief that hair removal inversely increases the risk of SSI by causing microscopic trauma of the skin. To minimize the potential of skin trauma, the use of clippers instead of razors has been proposed for preoperative hair removal. Clippers cut the hair close to the skin without actually touching it, whereas razors involve a sharp blade drawn directly over the skin. A third method for hair removal is the application of depilatory creams containing chemicals. The drawbacks are the necessity to leave the cream in place for approximately 15-20 minutes for the hair to be dissolved and the potential for allergic reactions. A Cochrane review, published in 2009 and updated in 2011, concluded that there was no statistically significant effect on SSI rates of hair removal 1. However, a significant harm was seen when hair removal with razors was compared with clipping. 2. PICO questions 1. Does hair removal affect the incidence of SSI? 2. -

Beyond Hair: the Significance of Wearing Locs – YO Magazine

); Spring 2020 Edition (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/spring-2020-edition/) Fall 2019 Edition (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/fall-2019-edition/) Missing Persons Features (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/missing- persons/) YO MAGAZINE (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/) THE UNIVERSITY, THE CITY AND THE PEOPLE OF YOUNGSTOWN (TM 2008) ABOUT YO MAGAZINE (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/WELCOME-TO-YO-MAGAZINE/) ! MISSION STATEMENT (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/WELCOME-TO-YO- MAGAZINE/ABOUT/) YO MAGAZINE ARCHIVE (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/LINKS-TO-PREVIOUS-EDITIONS-OF- YO-MAGAZINE/) CONTACT (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/CONTACT/) HOME (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/)/ 2020 (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/2020/)/ MAY (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/2020/05/)/ 12 (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/2020/05/12/)/ BEYOND HAIR: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF WEARING LOCS (HTTP://THEYOMAG.COM/INDEX.PHP/2020/05/12/BEYOND-HAIR-THE-SIGNIFICANCE- OF-WEARING-LOCS/) Search … SEARCH SPRING 2020 EDITION Spring 2020 Stories (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/spring- 2020-edition/spring-2020-stories/) FALL 2019 EDITION Fall 2019 Stories (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/fall- 2019-edition/fall-2019-stories/) SPRING 2019 EDITION Spring 2019 Stories (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/spring- 2019-edition/) FALL 2018 EDITION Fall 2018 Stories (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/fall- 2018-edition/fall-2018-stories/) SPRING 2018 EDITION Spring 2018 Stories (http://theyomag.com/index.php/category/spring- 2018-edition/spring-2018-stories/) SPRING 2020 EDITION -

“Hair” They Are: the Ideologies of Black Hair

THE YORK REVIEW, 9.1 (Spring 2013) “Hair” They Are: The Ideologies of Black Hair Tiffany Thomas woman’s hair is said to be her crowning glory and man- Aifestation of her femininity. Hair is considered a key indicator of a woman’s health and beauty. The Western standard of beauty defines beautiful hair as that which is long and prefer- ably straight. Having such a standard creates a hair hierarchy, with long straight hair on the top of the hair pyramid and Afri- can American hair on the bottom. A black woman’s hair is tradi- tionally dry, tightly coiled or curled. In order to attain the West- ern standard of beauty, the majority of African American women chemically straighten or “relax” their hair. This notion is embed- ded in media such as Sophisticate’s Black Hair Styles and Care Guide and other magazines featuring black women with straightened hair. However, more recently, there has been an increase in the number of black women returning to their natural hair texture; that is, they are no longer chemically straightening their hair (Healy, 2011). The decision to return to the natural texture of one’s hair is termed “going natural.” The media has noticed black women’s sudden movement toward natural hair and has begun to include more natural-haired African Americans in advertisements. Some reasons that black women decide to go natural are: to follow a healthier lifestyle, to explore curiosity about their natural texture, to support their daughters’ hair, and to save the time and energy they spend using relaxers.