Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

Holmer and Shelwick Environmental Report

Environmental Report Report for: Holmer & Shelwick Neighbourhood Area November 2019 hfdscouncil herefordshire.gov.uk Holmer and Shelwick NDP Environmental Report Contents Non-technical summary 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Methodology 3.0 The SEA Framework 4.0 Appraisal of Objectives 5.0 Appraisal of Options 6.0 Appraisal of Policies 7.0 Implementation and monitoring 8.0 Next steps Appendix 1: Initial SEA Screening Report Appendix 2: SEA Scoping Report incorporating Tasks A1, A2, A3 and A4 Appendix 3: Consultation responses from Scoping Report consultation Appendix 4: SEA Stage B incorporating Tasks B1, B2, B3 and B4 Appendix 5: Options Considered Appendix 6: Consultation responses to Reg14 Environmental Report Appendix 7: Stage D B2 and B3 on proposed changes Appendix 8: Consultation response to Reg16 Environmental Report Appendix 9: Modifications Appendix 10: Stage D D2 and D3 of modifications Appendix 11: Environmental Report checklist SEA: Environmental Report –Holmer and Shelwick (November 2019) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Non-technical summary Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is an important part of the evidence base which underpins Neighbourhood Development Plans (NDP), as it is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that environmental assets, including those whose importance transcends local, regional and national interests, are considered effectively in plan making. Holmer and Shelwick Parish Council has undertaken to prepare an NDP and this process has been subject to environmental appraisal pursuant to the SEA Directive. Holmer and Shelwick parish is situated to the north of Hereford city adjacent to the city boundary. Primarily residential development exists within the parish, either as growth on the edge of Hereford or small hamlets. -

Herefordshire. [ Kelly's

68 HEREFORD. HEREFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY'S Parish &c. Pop. Area. Rateable St. Martin, Peter Preece, Ross road. value. St. Nicholas, St~Nicholas parish 2,149 560 11,144 St. Peter and St. Owen, John J. Jones, 13 Commercial rd. St. Owen parish ,. 4,I07t 293 12,539 Putson is a hamlet in the parish of St. Martin, on the. St. Peter parish................. 2,821* 75 15,531 south bank of the river Wye, about I mile from Hereford, HoIrner parish within ..•.....• 1,808 1,157 11,4°3 and consists of a few scattered residences, all within the. Tupsley township 1,121 812 9,177 city liberties. Breinton parish within........ 436 1,647 3,658 Tupsley is a township, within the liberties of the city of The Vineyard parish..••.•...• 8 15 92 Hereford, from which it is I mile east-north-east; it was, Huntington township .•......• 137 556 1,279 formed into an ecclesiastical parish 13 March, 1866, from • Including 43 in H.M. Prison, and 201 officers and inmates in the parish of Hampton Bishop, and includes the civil parish the Workhonse. of the Vineyard and is in the Grimsworth hundred. t Including 95 in the Gilneral Infirmary, and 122 in the Working The church of St. Paul, a building of stone in the Early Boys' Home. English style, erected from designs by Mr. F. R. Kempson,. The population of the municipal wards in 1891 was : architect, of Hereford, at a cost of £2,35°, and consecratecl Ledbury, 8,057; Leominster, 7,572 and Monmouth, 4,638 ; 17 Nov. 1865; it consists of chancel, nave, aisles, soutlh total, 20,267. -

Land to the North of Roman Road, Holmer, Hereford, Hr1 1Le

CENTRAL AREA PLANNING SUB-COMMITTEE 13TH DECEMBER, 2006 6 DCCW2006/2619/O - RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (300 DWELLINGS) INCLUDING ACCESS FROM ROMAN ROAD, ESSENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURE, OPEN SPACE, BALANCING POND, LANDSCAPING, ROADS, PARKING, FOOTPATHS, CYCLEWAY AND ENGINEERING, EARTH WORKS AT LAND TO THE NORTH OF ROMAN ROAD, HOLMER, HEREFORD, HR1 1LE For: Crest Strategic Projects Ltd per D2 Planning, The Annex, 2 Oakhurst Road, Stoke Bishop, Bristol, BS9 3TQ Date Received: 9th August, 2006 Ward: Burghill, Grid Ref: 51327, 42272 Holmer & Lyde Expiry Date: 8th November, 2006 Local Member: Councillor Mrs. S.J. Robertson 1. Site Description and Proposal 1.1 The site extends to 12.8 hectares of undeveloped agricultural land located on the northern fringes of the city. The site is bordered to the south by the A4103 (Roman Road), the C1127 (Munstone Road) runs along the eastern boundary and unclassified road 72412 (Attwood Lane) borders the western boundary. Adjoining the site and immediately west of Attwood Lane are the Wentworth Park and Cleeve Orchard housing estates and adjoining the south east and south western corners of the site are existing predominantly detached residences including a vetinary surgery and Hopbine Hotel. A number of these existing properties either overlook or have gardens which back on to the development site. South of Roman Road occupying a corner location on the junction with Old School Lane is Pegasus Football Club, adjoining which is Hope Scott House and east of here are existing car garages. Adjoining the north western corner of the site is Holmer Court, a residential care home with the remainder of the boundaries being either enclosed by main roads or agricultural land. -

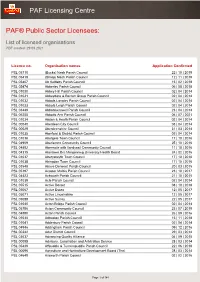

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

Welsh Contacts with the Papacy Before the Edwardian Conquest, C. 1283

WELSH CONTACTS WITH THE PAPACY BEFORE THE EDWARDIAN CONQUEST, C. 1283 Bryn Jones A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2019 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/18284 This item is protected by original copyright Welsh contacts with the Papacy before the Edwardian Conquest, c. 1283 Bryn Jones This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at the University of St Andrews June 2019 Candidate's declaration I, Bryn Jones, do hereby certify that this thesis, submitted for the degree of PhD, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for any degree. I was admitted as a research student at the University of St Andrews in September 2009. I received funding from an organisation or institution and have acknowledged the funder(s) in the full text of my thesis. Date Signature of candidate Supervisor's declaration I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages McDermid, R. T. W. How to cite: McDermid, R. T. W. (1980) The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7616/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk II BEVERIEY MINSTER FROM THE SOUTH Three main phases of building are visible: from the East End up to, and including, the main transepts, thirteenth century (commenced c.1230); the nave, fourteenth century (commenced 1308); the West Front, first half of the fifteenth century. The whole was thus complete by 1450. iPBE CONSTIOOTION AED THE CLERGY OP BEVERLEY MINSTER IN THE MIDDLE AGES. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Abstract and Illustrations

Abstract anti Elustrattons* Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.219, on 23 Sep 2021 at 20:28:30, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2042169900015777 THE title of this document, announcing that it contains an account of the household expenses of Richard, Bishop of Hereford, drawn up by John de Kemeseye, his chaplain, from Friday, the morrow after the feast of Saint Michael, 1289, to the said feast, 1290, presents several matters for inquiry and explanation. Before we enter upon its details, it may be observed, that the style of living and scale of expenditure here exhibited obviously suggest some investigation as to the origin of those means by which such an establish- ment was supported. The information to be obtained upon this subject is far from ample, but may be sufficient to afford a cursory view of this bishopric at a remote period, and some of the various changes it had under- gone in arriving at the condition in which it existed under Richard de Swinfield. As in every stage of society man must derive his primary sustenance from the earth and the waters, so in early and uncivilised times they were the most advantageously circumstanced who enjoyed the widest range of field, forest, and river; and princes, whose territories were wide in propor- tion to their population, made ample gifts to those whom they desired to establish in consequence and dependence. This was especially the case with regard to the Church, where Christianity prevailed, for they were influenced by the belief that what they conferred upon it was given to God and for their own eternal welfare. -

Holmer and Shelwick Planning Policy Assessment and Evidence Base Review

HOLMER AND SHELWICK PLANNING POLICY ASSESSMENT AND EVIDENCE BASE REVIEW January 1, 2017 1 HOLMER AND SHELWICK PLANNING POLICY ASSESSMENT AND EVIDENCE BASE REVIEW January 1, 2017 2 HOLMER AND SHELWICK PLANNING POLICY ASSESSMENT AND EVIDENCE BASE REVIEW Contents Document Overview Page 1.0 Introduction 5 2.0 National Planning Policy 6 2.1 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) 6 2.2 National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG) 12 2.3 Ministerial Statements 16 3.0 Herefordshire Planning Policies 20 3.1 Adopted Herefordshire Local Plan – Core Strategy 2011 – 2031 20 3.2 Adopted Herefordshire Unitary Development Plan, 2007 44 4.0 Local Plan Evidence Base 45 4.1 Housing 45 4.2 Employment 60 4.3 Transport 61 4.4 Green Infrastructure 62 4.5 Landscape Character 64 4.6 Built Heritage 73 4.7 Flood Risk 74 4.8 Infrastructure 76 5.0 Conclusion 79 January 1, 2017 3 HOLMER AND SHELWICK PLANNING POLICY ASSESSMENT AND EVIDENCE BASE REVIEW Document Overview • Holmer and Shelwick is a parish in Herefordshire about 3 km north of Hereford. It comprises the village of Holmer and the smaller settlements of Munstone, Shelwick and Shelwick Green. The A49 runs north - south through the parish as does the Herefordshire and Gloucestershire Canal bisects the parish. • The neighbourhood development plan area covers about 555 hectares and the population of the Parish was recorded as 1386 in the 2011 Census (Office for National Statistics). • The key policy documents which are relevant to the area are: o National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) o Adopted Herefordshire Local Plan -Core Strategy 2011-2031 • Holmer and Shelwick lie within Hereford Housing Market Area and includes the Holmer West Northern Urban Expansion Area (Policy HD4) • In the Herefordshire Local Plan Core Strategy 2011 – 2031, Munstone and Shelwick are identified as other settlements where proportionate housing is appropriate. -

Parish, Town Councils Submissions to the Herefordshire County Council Electoral Review

Parish, Town Councils submissions to the Herefordshire County Council electoral review This PDF document contains 29 submissions from Parish and Town Councils. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. SUBMISSION TO THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FROM BREINTON PARISH COUNCIL ELECTORAL REVIEW OF HEREFORDSHIRE COUNCIL 2012 Breinton is a small rural parish (396 Council tax paying households in 2012, 711 registered electors in 2011) immediately to the west of Hereford city. The boundaries of the parish are as follows: To the north and west – Stretton Sugwas & Kenchester parishes, To the south - the River Wye, and To the east – Hereford City (St Nicholas and Three Elms wards) The four parishes of Breinton, Stretton Sugwas, Kenchester and Credenhill currently form the Credenhill ward of Herefordshire Council. Breinton is currently un-warded and so, on our understanding of electoral law, the parish cannot be split between different county wards Breinton parish council believes that the current arrangement of wards for Herefordshire Council in its area should continue and not be changed by the current review for the following reasons. 1) There are strong similarities between Breinton, Kenchester and Stretton Sugwas including the scatter of small settlements, employment of residents, age profile, open & rural landscape and the issues facing local councillors and the people they represent. These parishes have been designated by Herefordshire Council as part of the Hereford rural sub-locality i.e. the rural fringe of the historic city. -

Interactions Between Medieval Clergy and Laity in a Regional Context

Clergy and Commoners: Interactions between medieval clergy and laity in a regional context Andrew W. Taubman Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Centre for Medieval Studies 2009 Taubman 2 Abstract This thesis examines the interactions between medieval clergy and laity, which were complex, and its findings trouble dominant models for understanding the relationships between official and popular religions. In the context of an examination of these interactions in the Humber Region Lowlands during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, this thesis illustrates the roles that laity had in the construction of official and popular cultures of medieval religion. Laity and clergy often interacted with each other and each other‟s culture, with the result that both groups contributed to the construction of medieval cultures of religion. After considering general trends through an examination of pastoral texts and devotional practices, the thesis moves on to case studies of interactions at local levels as recorded in ecclesiastical administrative documents, most notably bishops‟ registers. The discussion here, among other things, includes the interactions and negotiations surrounding hermits and anchorites, the complaints of the laity, and lay roles in constructing the religious identity of nuns. The Conclusion briefly examines the implications of the complex relationships between clergy and laity highlighted in this thesis. It questions divisions between cultures of official and popular religion and ends with a short case study illustrating how clergy and laity had the potential to shape the practices and structures of both official and popular medieval religion. Taubman 3 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................