AZWILD Fall 0506

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

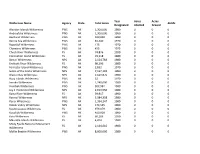

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Kaibab National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Kaibab National Forest Forest Service Southwestern Potential Wilderness Area Region September 2013 Evaluation Report The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Kanab Creek Wilderness Kaibab National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Inventory of Potential Wilderness Areas .................................................................................................. 2 Evaluation of Potential Wilderness Areas ............................................................................................... -

Grand Canyon Council Oa Where to Go Camping Guide

GRAND CANYON COUNCIL OA WHERE TO GO CAMPING GUIDE GRAND CANYON COUNCIL, BSA OA WHERE TO GO CAMPING GUIDE Table of Contents Introduction to The Order of the Arrow ....................................................................... 1 Wipala Wiki, The Man .................................................................................................. 1 General Information ...................................................................................................... 3 Desert Survival Safety Tips ........................................................................................... 4 Further Information ....................................................................................................... 4 Contact Agencies and Organizations ............................................................................. 5 National Forests ............................................................................................................. 5 U. S. Department Of The Interior - Bureau Of Land Management ................................ 7 Maricopa County Parks And Recreation System: .......................................................... 8 Arizona State Parks: .................................................................................................... 10 National Parks & National Monuments: ...................................................................... 11 Tribal Jurisdictions: ..................................................................................................... 13 On the Road: National -

Management Area Direction

Chapter 5. Management Area Direction Riparian vegetation along the upper Verde River Introduction The 1987 “Prescott National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan” included specific direction on how to manage different land areas based on ecological characteristics. In this revised plan, we have addressed ecological variation using other methods (see chapters 1 and 2). Management area boundaries were selected based on human geographic boundaries, so that guidance in response to social or economic issues could be better identified to meet each community’s needs. As plan revision steps progressed, we asked ourselves which aspects of the plan needed to be addressed differently based on geographic location. The response was that recreation needs and desires were likely to be different for various parts of the Prescott NF. In addition, the Verde Valley area had specific desires relative to maintaining and enhancing open space. The Prescott NF was divided into human geographic areas based on descriptions of communities located near and within the Prescott NF (Komar and Schultz, 2007). Using methods developed by James Kent and Associates, geographic areas were mapped indicating where people from various communities feel strongly about conditions and events. Communities were then invited to develop community visions for the Prescott NF and other surrounding lands. Land and Resource Management Plan for the Prescott NF 97 Chapter 5. Management Area Direction In a more recent effort to develop a recreation strategy for the Prescott NF, similar boundaries were used to divide the forest and surrounding area into three zones. In this plan, those zone boundaries were adjusted slightly and are called geographic areas. -

AZWILD Fall 0506

NEWSLETTER OF THE ARIZONA WILDERNESS COALITION ARIZONA WILDWILD Growing Pains East Clear Creek Selling Green Amid the Glitz The Greatest Job in the World Don’t Move a Mussel SUMMER 2008 Arizona Wilderness Coalition Main Office THOUGHTS FROM THE KGB 520-326-4300 P.O. Box 40340, Tucson, AZ 85717 Growing Stronger and Smarter Phoenix Office 602-252-5530 P.O. Box 13524 by Kevin Gaither-Banchoff Phoenix, AZ 85002 Central Arizona Field Office rizona’s last wild public lands remain at risk. result of political and social pressures. 928-717-6076 They continue to be threatened by myriad Alone, many of us think we don’t have the power P.O. Box 2741 pressures – some that are unique to our to affect change or make our voices heard. When many Prescott, AZ 86302 Asouthwestern desert home and some that diverse individuals, business, and organizations speak are common to wild places across the west. Almost all up with a similar preservation/protection message, we Grand Canyon Field Office are threats that we--as individuals, businesses, and have the power to make positive changes and combat 928-638-2304 conservation organizations--can work to eliminate or the threats facing Arizona’s wild places. As we move P.O. Box 1033 minimize through education, constant engagement through 2008, we hope to permanently protect the Grand Canyon, AZ 86203 with allied stakeholders and our elected officials, and Tumacacori Highlands as Arizona’s first wilderness in cultivating a sense of land and water stewardship 17 years, see Fossil Creek become Arizona’s second Sky Islands Field Office amongst the public. -

Drake Cement, LLC Fo

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Drake Cement Limestone Quarry Project Prescott National Forest Project proponent: Drake Cement, LLC For submittal to: United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Prescott National Forest Prepared by: Transcon Infrastructure, Inc. (dba Transcon Environmental) 3740 East Southern Avenue, Suite 218 Mesa, Arizona 85206 (480) 807-0095 September 2006 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................1 1.1 Document Structure and Purpose.........................................................................................1 -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress. -

Wilderness Need Assessment Instructions

2/11/11 Updated Coconino National Forest Wilderness Need Evaluation Introduction Anything in this document that has been changed since the last version has been highlighted in Green. The purpose of the Wilderness Need Assessment is to identify the need for additional wilderness on the Coconino National Forest and in the US Forest Service’s Southwest Region (Region 3 or Region) based on a variety of factors including visitor demand, the need to provide protections for various fish, wildlife, and plant species, and provididsng a reasonable representation of landforms and ecosystems within the National Wilderness Preservation System. Forest Service Handbook (FSH) 1909.12, Subsection 72.3 describes the factors that are to be considered. The following report provides the complete documentation of consideration of these factors following the Forest Service’s Southwest Region working group guidance. Because most of these factors are intended to be evaluated at a regional scale, the majority of table and figures were created using data from the Region 3 Wilderness Needs Evaluation (Forest Service 2007a). Factor #1 Factor #1, Item #1 The location, size, and type of other wildernesses in the general vicinity and their distance from the proposed area. 1. How many, what size (# of acres), and what types of other wilderness areas exist within the general vicinity of your forest (within 100 air miles)? There are 15 wilderness areas within the Coconino National Forest (the Forest or Coconino NF) and there are 32 Wilderness Areas within 100 air miles of the Coconino NF, including those on other National Forests (Tonto, Prescott, and Kaibab National Forests), National Park Service (NPS) administered lands, and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administered lands (Table 1). -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2020 Forest Service WO Lands FS–383 November 2020 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To find: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters (cm) Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters (m) Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers (km) Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares (ha) Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters (m2) Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters (m) Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers (km2) Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms (kg) United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS–383 System November 2020 As of September 30, 2020 USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250–0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo: Mount Ogden, Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, Utah Photo by Eric Greenwood, USDA Forest Service, Region 4, Recreation Lands & Minerals i Statistics are current as of: 10/19/2020 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 193,041,851 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), administers 134 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 449 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers

G4212 PACIFIC AND MOUNTAIN STATES. REGIONS, G4212 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .G7 Great Basin [geological basin] .I3 Idaho and California Stage Road 1502 G4222 ROCKY MOUNTAIN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G4222 FEATURES, ETC. .B4 Bear River [ID, UT & WY] .B6 Bonneville, Lake .C3 Caribou National Forest .C35 Caribou-Targhee National Forest .C65 Continental Divide National Scenic Trail .G7 Green River .G72 Green River Formation .M3 Mancos Shale .R6 Rocky Mountains 1503 G4232 PACIFIC STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G4232 ETC. .C3 Cascade Range .C55 Coast Ranges .C6 Coasts .I5 Interstate 5 .P3 Pacific Crest Trail 1504 G4242 PACIFIC NORTHWEST. REGIONS, NATURAL G4242 FEATURES, ETC. .B45 Belt Supergroup .C62 Columbia River .I5 Inland Empire .K3 Kaniksu National Forest .K6 Kootenai River .N4 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .P46 Pend Oreille River .S6 Snake River [Wyo.-Wash.] .S62 Snake River [wild & scenic river] 1505 G4252 MONTANA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G4252 .A2 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness [MT & WY] .A23 Absaroka Range [MT & WY] .A6 Anaconda Pintler Wilderness .A63 Andesite Mountain .A8 Ashley Lake State Recreation Area .B12 Baker, Lake [Fallon County] .B126 Baker Watershed Dam .B13 Bannack State Park .B17 Bannock Pass .B2 Bearpaw Mountains .B25 Bearpaw Ski Area .B28 Bearpaw State Recreation Area .B29 Beartooth Mountains [MT & WY] .B3 Beartooth Plateau .B35 Beartooth State Recreation Area .B4 Beaverhead National Forest .B42 Beaverhead River .B423 Beavertail Hill State Recreation Area .B425 Beef Trail Ski Area .B432 Benton Lake National -

MAPS ● MAPPING SOFTWARE for the WESTERN UNITED STATES Adler Publishing Company Inc

GUIDEBOOKS ● TRAIL GUIDES ● ATLASES ● MAPS ● MAPPING SOFTWARE FOR THE WESTERN UNITED STATES adler publishing company inc 2011 catalog 4-WHEELING ● CAMPING ● FISHING ● SCENIC DRIVING ● ATVs ● SNOWMOBILING HORSEBACK RIDING ● HIKING ● DIRT BIKING ● MOUNTAIN BIKING HISTORIC GHOST TOWNS, MINING CAMPS AND CLIFF DWELLINGS new for 2011 Nevada Trails Colorado Fishing Southern Region Sixth Edition Completely Revised and Redesigned See page 7 for details See page 9 for details 2 New Benchmark 9 New Trails Illustrated Maps, Recreation Maps TOPO! Explorer; and TOPO! Explorer See page 13 for details Deluxe See pages 14, 17, and 19 for details 2 new for 2011 butler motorcycle maps Butler Motorcycle Maps identify the most dramatic and thrilling rides in each state. The experts at Butler have ridden and researched each and every road segment detailed on these maps. No matter what you ride, from sport bike enthusiast to dual sport adventurer, chopper rider to two up tourers, the Butler team has you covered. The best segments of road in the state are rated from G1 to G3, providing focused information about the riding experience. The rating system is based on features such as high mountain passes, deep canyons, sweepers, switchbacks, twisties, and remarkable scenery. The rides designated as Lost Highways are stretches of road that seem lost in time. Traveling through untouched landscapes void of population, the roads’ faded centerlines and crumbling shoulders are the only remnants of a purposeful past. The Paved Mountain Trails are paths of pavement through remote forests and mountain ranges. All exceptionally tight, twisty, and remote, these stunning routes have even the most seasoned riders coming back for more. -

Grazing Data by Wilderness

Year Acres Acres Wilderness Name Agency State Total Acres AUMs Designated Allotted Grazed Aleutian Islands Wilderness FWS AK 1,300,000 1980 0 0 0 Andreafsky Wilderness FWS AK 1,300,000 1980 0 0 0 Becharof Wilderness FWS AK 400,000 1980 0 0 0 Bering Sea Wilderness FWS AK 81,340 1970 0 0 0 Bogoslof Wilderness FWS AK 175 1970 0 0 0 Chamisso Wilderness FWS AK 455 1975 0 0 0 Chuck River Wilderness FS AK 74,876 1990 0 0 0 Coronation Island Wilderness FS AK 19,118 1980 0 0 0 Denali Wilderness NPS AK 2,124,783 1980 0 0 0 Endicott River Wilderness FS AK 98,396 1980 0 0 0 Forrester Island Wilderness FWS AK 2,832 1970 0 0 0 Gates of the Arctic Wilderness NPS AK 7,167,192 1980 0 0 0 Glacier Bay Wilderness NPS AK 2,664,876 1980 0 0 0 Hazy Islands Wilderness FWS AK 32 1970 0 0 0 Innoko Wilderness FWS AK 1,240,000 1980 0 0 0 Izembek Wilderness FWS AK 307,982 1980 0 0 0 Jay S. Hammond Wilderness NPS AK 2,619,550 1980 0 0 0 Karta River Wilderness FS AK 39,917 1990 0 0 0 Katmai Wilderness NPS AK 3,384,358 1980 0 0 0 Kenai Wilderness FWS AK 1,354,247 1980 0 0 0 Kobuk Valley Wilderness NPS AK 174,545 1980 0 0 0 Kootznoowoo Wilderness FS AK 979,079 1980 0 0 0 Koyukuk Wilderness FWS AK 400,000 1980 0 0 0 Kuiu Wilderness FS AK 60,183 1990 0 0 0 Maurelle Islands Wilderness FS AK 4,814 1980 0 0 0 Misty Fjords National Monument FS AK 2,144,010 1980 0 0 0 Wilderness Mollie Beattie Wilderness FWS AK 8,000,000 1980 0 0 0 Noatak Wilderness NPS AK 5,765,427 1980 0 0 0 Nunivak Wilderness FWS AK 600,000 1980 0 0 0 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck FS AK 46,758 1980