Ordinary Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestinian Refugees: Adiscussion ·Paper

Palestinian Refugees: ADiscussion ·Paper Prepared by Dr. Jan Abu Shakrah for The Middle East Program/ Peacebuilding Unit American Friends Service Committee l ! ) I I I ' I I I I I : Contents Preface ................................................................................................... Prologue.................................................................................................. 1 Introduction . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 The Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem .. .. .. .. .. 3 • Identifying Palestinian Refugees • Counting Palestinian Refugees • Current Location and Living Conditions of the Refugees Principles: The International Legal Framework .... .. ... .. .. ..... .. .. ....... ........... 9 • United Nations Resolutions Specific to Palestinian Refugees • Special Status of Palestinian Refugees in International Law • Challenges to the International Legal Framework Proposals for Resolution of the Refugee Problem ...................................... 15 • The Refugees in the Context of the Middle East Peace Process • Proposed Solutions and Principles Espoused by Israelis and Palestinians Return Statehood Compensation Resettlement Work of non-governmental organizations................................................. 26 • Awareness-Building and Advocacy Work • Humanitarian Assistance and Development • Solidarity With Right of Return and Restitution Conclusion .... ..... ..... ......... ... ....... ..... ....... ....... ....... ... ......... .. .. ... .. ............ -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

2009 Annual Report Available to Download Here

CONFLICT IN CITIES AND THE CONTESTED STATE Everyday life and the possibilities for transformation in Belfast, Jerusalem and other divided cities ANNUAL REPORT 2009 w w w . c o n f l i c t i n c i t i e s . o r g Conflict in Cities CONFLICT IN CITIES AND THE CONTESTED STATE Annual Report March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p1 Project Description p2 Research Modules Contents p3-14 Graduate Programme p15-18 Workshops p19-20 Project Activities p21-22 Linked Cities p23 Project Team p24-29 Ethics and Project Management p30 Outputs p31-35 Introduction By the time of the Advisory Council Annual Meeting in March 2009, we shall be halfway through the second year of ‘Conflict in Cities and the Contested State’. The past twelve months of the Project have been like Janus, looking inward to allow consolidation of the team structures, and concurrently, projecting an outward gaze to investigate like-minded projects and recruit new partners. The research groups in each of the three Universities – Cambridge, Exeter and Queen’s Belfast – are now well established. In September 2008, seven postgraduate students joined Conflict in Cities, completing the remaining part of the Project team. One new RA was hired at Queen’s. As the Project grows, it has been necessary to encourage bonding at all levels across the university teams, including students, researchers and investigators. Our first International Workshop, held in Belfast in September 08, provided an important opportunity to make contacts and discuss the first year’s research. Throughout the year, aided by various electronic means as well as face to face meetings, we have instituted a regular schedule of discussions amongst the various groups in Conflict in Cities. -

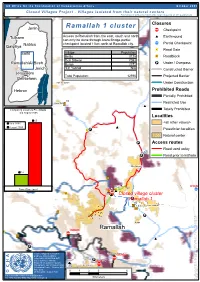

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920- 1948

THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2017 2 This dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of an invisible generation of leftists that were active in Lebanon, and more generally in the Levant, between the years 1920 and 1948. It chronicles the foundation and development of this intellectual milieu within the political Left, and how intellectuals interpreted leftist principles and struggled to maintain a fluid, ideologically non-rigid space, in which they incorporated an array of ideas and affinities, and formulated their own distinct worldviews. More broadly, this study is concerned with how intellectuals in the post-World War One period engaged with the political sphere and negotiated their presence within new structures of power. It explains the social, political, as well as personal contexts that prompted intellectuals embrace certain ideas. Using periodicals, personal papers, memoirs, and collections of primary material produced by this milieu, this dissertation argues that leftist intellectuals pushed to politicize the role and figure of the ‘intellectual’. -

Palestinians; from Village Peasants to Camp Refugees: Analogies and Disparities in the Social Use of Space

Palestinians; From Village Peasants to Camp Refugees: Analogies and Disparities in the Social Use of Space Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Maraqa, Hania Nabil Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 06:50:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/190208 PALESTINIANS; FROM VILLAGE PEASANTS TO CAMP REFUGEES: ANALOGIES AND DISPARITIES IN THE SOCIAL USE OF SPACE by Hania Nabil Maraqa _____________________ Copyright © Hania Nabil Maraqa 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 4 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all those who made this research a reality. Special appreciation goes to my advisor, Dennis Doxtater, who generously showed endless support and guidance. -

Banditry and Popular Rebellion in Palestine Abu Jilda Entered

Alex Winder Abu Jilda, Anti-Imperial Anti-Hero: Banditry and Popular Rebellion in Palestine Abu Jilda entered Ramallah And he took their cattle and did not fear Allah. Beneath Abu Jilda, a filly, mashallah, Like December lightning. —Palestinian popular song, 1930s1 From 1933 to 1934, the administration and public of Palestine were gripped by the exploits of Muhammad Hamad al-Mahmud, better known as Abu Jilda, a highway robber from the village of Tammun, a little over twenty kilometers northeast of Nablus. Abu Jilda began to gain a certain notoriety in the spring of 1933, after he and his band of men undertook a series of highway robberies. However, he achieved real fame in Palestine after he shot and killed an Arab policeman, Husayn al-`Assali, spurring an intense police hunt. His ability to evade the British authorities was trumpeted in the Arabic-language press and by the time he was captured in spring of 1934, Abu Jilda may have been the most notorious individual in Palestine.2 He was tried, sentenced to death, and hanged in Jerusalem in August 1934, to great public interest, but his prominence quickly faded, overtaken by the activities of `Izz al-Din al-Qassam and his followers and the outbreak of the Great Revolt in 1936. Although largely relegated to a footnote in the history of Palestinian resistance to British and Zionist forces during the Mandate period, the story of Abu Jilda can help to illuminate how the kinds of economic, political, and social changes that characterized Palestine under the British Mandate allowed for the emergence of such a figure. -

Al-Bireh Ramallah Salfit

Biddya Haris Kifl Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Az Zawiya (Salfit) Talfit Salfit As Sawiya Qusra Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Deir Ballut Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Turmus'ayya Al Lubban al Gharbi 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Bani Zeid Deir as Sudan Sinjil Rantis Jilijliya 'Ajjul An Nabi Salih (Bani Zeid al Gharbi) Al Mughayyir (Ramallah) 'Abud Khirbet Abu Falah Umm Safa Deir Nidham Al Mazra'a ash Sharqiya 'Atara Deir Abu Mash'al Jibiya Kafr Malik 'Ein Samiya Shuqba Kobar Burham Silwad Qibya Beitillu Shabtin Yabrud Jammala Ein Siniya Bir Zeit Budrus Deir 'Ammar Silwad Camp Deir Jarir Abu Shukheidim Jifna Dura al Qar' Abu Qash At Tayba (Ramallah) Deir Qaddis Al Mazra'a al Qibliya Al Jalazun Camp 'Ein Yabrud Ni'lin Kharbatha Bani HarithRas Karkar Surda Al Janiya Al Midya Rammun Bil'in Kafr Ni'ma 'Ein Qiniya Beitin Badiw al Mus'arrajat Deir Ibzi' Deir Dibwan 'Ein 'Arik Saffa Ramallah Beit 'Ur at Tahta Khirbet Kafr Sheiyan Al-Bireh Burqa (Ramallah) Beituniya Al Am'ari Camp Beit Sira Kharbatha al Misbah Beit 'Ur al Fauqa Kafr 'Aqab Mikhmas Beit Liqya At Tira Rafat (Jerusalem) Qalandiya Camp Qalandiya Beit Duqqu Al Judeira Jaba' (Jerusalem) Al Jib Jaba' (Tajammu' Badawi) Beit 'Anan Bir Nabala Beit Ijza Ar Ram & Dahiyat al Bareed Deir al Qilt Kharayib Umm al Lahim QatannaAl Qubeiba Biddu An Nabi Samwil Beit Hanina Hizma Beit Hanina al Balad Beit Surik Beit Iksa Shu'fat 'Anata Shu'fat Camp Al Khan al Ahmar (Tajammu' Badawi) Al 'Isawiya. -

Cultural Heritage for the Future

Sida Evaluation 04/30 Cultural Heritage for the Future An Evaluation Report of Nine years’ work by Riwaq for the Palestinian Heritage 1995–2004 Lennart Edlund Department for Democracy and Social Development Cultural Heritage for the Future An Evaluation Report of Nine years’ work by Riwaq for the Palestinian Heritage 1995–2004 Lennart Edlund Sida Evaluation 04/30 Department for Democracy and Social Development This report is part of Sida Evaluations, a series comprising evaluations of Swedish development assistance. Sida’s other series concerned with evaluations, Sida Studies in Evaluation, concerns methodologically oriented studies commissioned by Sida. Both series are administered by the Department for Evaluation and Internal Audit, an independent department reporting directly to Sida’s Board of Directors. This publication can be downloaded/ordered from: http://www.sida.se/publications Author: Lennart Edlund The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida Evaluation 04/30 Commissioned by Sida, Department for Democracy and Social Development and Department for Africa Copyright: Sida and the author Registration No.: 2003-2425 Date of Final Report: June 2004 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, 2004 Art. no. Sida4374en ISBN 91-586-8494-8 ISSN 1401—0402 SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: SE-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Office: Sveavägen 20, Stockholm Telephone: +46 (0)8-698 50 00. Telefax: +46 (0)8-20 88 64 E-mail: [email protected]. Homepage: http://www.sida.se Table of Contents Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Background ......................................................................................................... 8 1.1 The threat to cultural heritage............................................................................................ -

From Camp to City. Obstacles to Overcome

From camp to city. Obstacles to overcome Jorren Bosmans Student number: 01303878 Supervisor: Prof. Joachim Declerck Master's dissertation submitted in order to obtain the academic degree of Master of Science in de ingenieurswetenschappen: architectuur Academic year 2018-2019 Acknowledgements To professor Joachim Declerck, who provided assistance and guidance in a field that was previously unknown to me. To Yousef Abu-Safieh and his wife Maghboobe, who presented me with a home in a foreign country and cared for me like a son. To Taha Albess and Mohamad Elayan, who helped me understand the inner workings of the Palestinian refugee crisis and who work daily to lighten the burden of the many refugees in the West bank. To Mousa Anbar, who provided inside knowledge on life in Jalazone camp and who showed me the most interesting places inside the camp’s urban jungle. The author gives permission to make this master dissertation available for consultation and to copy parts of this master dissertation for personal use. In all cases of other use, the copyright terms have to be respected, in particular with regard to the obligation to state explicitly the source when quoting results from this master dissertation. 28/05/2019 Abstract In recent decades, refugee camps have existed for increasingly longer periods of time. Protracted refugee situations have become the new norm due to prolonged conflicts and due to both humanitarian agencies and host governments preferring to keep refugees in camps. Although refugee workers are aware of long-term possibilities, in practice refugee care is mostly aimed at the initial emergency assistance. -

Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in the Ramallah & Al

Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in the Ramallah & Al Bireh Governorate ARIJ welcomes any comments or suggestions regarding the material published herein and reserves all copyrights for this publication. This publication is available on the project’s homepage: http://proxy.arij.org/vprofile/ramallah and ARIJ homepage: http://www.arij.org Copyright © The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem (ARIJ) 2014 Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) and civil society organizations for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. Editors Jad Isaac Roubina Ghattas Nader Hrimat Contributors Iyad Khalifeh Elia Khalilieh Ayman Abu Zahra Juliette Bannoura Enas Bannourah Nadine Sahouri Hamza Halaybeh Flora Al-Qassis Ronal El Zughayyar Anas Al Sayeh Poppy Hardee Issa Zboun Jane Hilal Suhail Khalilieh Table Of Contents PART ONE: Introduction................................................................................................................ 6 Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in Ramallah & Al Bireh Governorate....................7 1.1. Project Description and Objectives:.................................................................... 7 1.2. Project Activities:................................................................................................