Environmental Profile for the West Bank Volume 4 Ramallah District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees the United Nations and Palestinian Refugees

UNRWA CONTACTS: Public Information Office Gaza HQ P.O. Box 140157 Amman, Jordan 11814 Tel.: +972 8 677 7527 Fax: +972 8 677 7697 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unrwa.org UNHCR CONTACTS: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 94, Rue de Montbrillant Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Genève 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 739 8111 Fax: +41 22 739 7334 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unhcr.org Front cover: Palestinians fleeing to Jordan,June 1967 / UNRWA Back cover: Tents had just been replaced by cement block houses at Khan Younis refugee camp, Gaza Strip, 1955 / UNRWA Inside cover: Baqa’a refugee camp, Jordan, 1969 / UNRWA Opposite: A Palestine refugee with her grandson in Beach refugee camp, Gaza Strip / UNRWA All UNRWA photographs courtesy of UNRWA Photo Archive & Steve Sabella January 2007 2 The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees n December 1949, the United Nations General IAssembly established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to provide humanitarian relief to the more than 700,000 refugees and displaced persons who had been forced to flee their homes in Palestine as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Also in December 1949, the United Nations General Assembly decided to set up the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner / 1950s UNRWA for Refugees (UNHCR), as Suffering and fortitude of young and old in of 1 January 1951, with the Jalazone refugee camp, West Bank principal aim of dealing with refugees in Europe of Palestine refugees, that is, refugees left homeless by World War from the territory that had been under II. -

View Daily Report

Israeli Violations' Activities in the oPt 16 May 2017 The daily report highlights the violations behind Israeli home demolitions and demolition threats The Violations are based on in the occupied Palestinian territory, the reports provided by field workers confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting and\or news sources. and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of settlements and erection of outposts, the brutality The text is not quoted directly of the Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers from the sources but is edited for violence against Palestinian civilians and clarity. properties, the erection of checkpoints, the The daily report does not construction of the Israeli segregation wall and necessarily reflect ARIJ’s opinion. the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • A Palestinian fisherman who was shot and injured by Israeli occupation Army (IOA) off the coast of the besieged Gaza Strip earlier succumbed to his wounds. Muhammad Majid Bakr, a 23-year-old resident from the al-Shati refugee camp, was shot by Israeli naval forces at around 8:30 a.m. on Monday morning while fishing off the coast of Gaza with his brother Umran Majid Bakr. He had been shot in the chest, and was still bleeding when Israeli naval ships surrounded their fishing boat and detained Bakr. (Maannews 16 May 2017) 1 • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) broke into a blacksmith workshop in Deir al-Ghosun town near Tulkarem city and confiscated its machinery and equipment before closing the workshop. (PALINFO 16 May 2017) • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained three Palestinian fishermen off the coast of Al-Sudaniyeh, northwest of Gaza city. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Secretariats of Roads Transportation Report 2015

Road Transportation Report: 2015. Category Transfer Fees Amount Owed To lacal Remained No. Local Authority Spent Amount Clearing Amount classification 50% Authorities 50% amount 1 Albireh Don’t Exist Municipality 1,158,009.14 1,158,009.14 0.00 1,158,009.14 2 Alzaytouneh Don’t Exist Municipality 187,634.51 187,634.51 0.00 187,634.51 3 Altaybeh Don’t Exist Municipality 66,840.07 66,840.07 0.00 66,840.07 4 Almazra'a Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 136,262.16 136,262.16 0.00 136,262.16 5 Banizeid Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 154,092.68 154,092.68 0.00 154,092.68 6 Beitunia Don’t Exist Municipality 599,027.36 599,027.36 0.00 599,027.36 7 Birzeit Don’t Exist Municipality 137,285.22 137,285.22 0.00 137,285.22 8 Tormos'aya Don’t Exist Municipality 113,243.26 113,243.26 0.00 113,243.26 9 Der Dibwan Don’t Exist Municipality 159,207.99 159,207.99 0.00 159,207.99 10 Ramallah Don’t Exist Municipality 832,407.37 832,407.37 0.00 832,407.37 11 Silwad Don’t Exist Municipality 197,183.09 197,183.09 0.00 197,183.09 12 Sinjl Don’t Exist Municipality 158,720.82 158,720.82 0.00 158,720.82 13 Abwein Don’t Exist Municipality 94,535.83 94,535.83 0.00 94,535.83 14 Atara Don’t Exist Municipality 68,813.12 68,813.12 0.00 68,813.12 15 Rawabi Don’t Exist Municipality 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16 Surda - Abu Qash Don’t Exist Municipality 73,806.64 73,806.64 0.00 73,806.64 17 Hay Alkarama Don’t Exist Village Council 7,551.17 7,551.17 0.00 7,551.17 18 Almoghayar Don’t Exist Village Council 71,784.87 71,784.87 0.00 71,784.87 19 Alnabi Saleh Don’t Exist Village Council -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

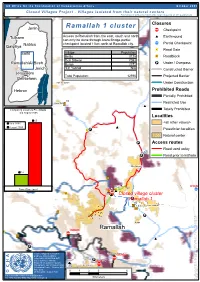

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Israeli Violations' Activities in the Opt 19 November 2018

Israeli Violations' Activities in the oPt 19 November 2018 The daily report highlights the violations behind Israeli home demolitions and demolition threats The Violations are based on in the occupied Palestinian territory, the reports provided by field workers confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting and\or news sources. and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of The text is not quoted directly settlements and erection of outposts, the brutality from the sources but is edited for of the Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers clarity. violence against Palestinian civilians and properties, the erection of checkpoints, the The daily report does not construction of the Israeli segregation wall and necessarily reflect ARIJ’s opinion. the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded the al-Mazra’a al- Gharbiyya village, northwest of Ramallah, before detaining Bassel Ladawda, and the head of Birzeit University Students’ Council, Yahia Rabea’. (IMEMC 19 November 2018) • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded Deir Abu Mash’al, and fired many live rounds, rubber-coated steel bullets, gas bombs and 1 concussion grenades, at local youngsters who protested the invasion. The IOA searched homes in Deir Abu Mash’al village, west of Ramallah, and detained Omar Mahmoud Rabea’. The IOA fired live rounds at a Palestinian car in the village, wounding four residents including one who suffered a serious injury. (IMEMC 19 November 2018) Israeli Arrests • In Nablus, the Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained Ezzeddin Marshoud, Mahmoud Faisal Qawareeq, Anas Eshteyya and Nasr Shreim. -

Am'ari Refugee Camp

unrwa west bank Photo by Dominiek Benoot profile: am’ari camp ramallah and al-bireh governorate Overview UNRWA in Am’ari camp Am’ari camp, located east of Ramallah city General information UNRWA in Am’ari camp in al-Bireh municipality, is one of the • Established: 1949 Main UNRWA installations: smallest camps in the West Bank. Before the • Size: .096 sq km • Four schools first intifada, many refugees living in Am’ari • Population before 1967 (OCHA): 3,930 • One health centre camp were able to move to surrounding • Estimated population (PCBS): 6,100 villages and cities. However, the • Registered persons (UNRWA): 12,000 UNRWA employees working in Am’ari construction of the West Bank Barrier, • Estimated density: 72,916 per sq km camp: 111 expansion of Ramallah and rising property • Places of origin: Mainly Jaa, Lydd, Remleh, • Education: 71 • Health: 24 prices has meant that this has become and Jerusalem • Relief and Social Services: 3 prohibitively expensive for most residents. * Many refugees left the camp and settled in Ramallah, Bireh, Bitunia, and • Sanitation services: 10 Um al-Sharayet neighbourhoods but maintained their registrered The growing population remains a residence in Am’ari camp. • Administration: 3 challenge for service provision as well as on the existing infrastructure in the camp, while also contributing to overcrowding Relief, Social Services and Emergency Response and poor living conditions. UNRWA social workers conduct regular home visits in the camp to identify families requiring special assistance. Additionally, through the Social Safety Net Programme, Residents in Am’ari report that unemploy- UNRWA provides food parcels to approximately 1,330 impoverished refugees in the camp ment in the camp is rising, especially (approximately 11 per cent of registered persons in the camp). -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00

Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00 Tulkarm- Israeli forces destroy a house belonging to a Palestinian family in Far’one village. Reuters Israeli forces continue systematic attacks against Palestinian civilians and property in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) In a new extra-judicial execution, Israeli forces killed a member of an armed group and wounded 3 civilians, including a child, in the Gaza Strip A Palestinian civilian died as he was previously wounded by the Israeli forces in the northwest of Beit Lahia in the northern Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued to use excessive force against peaceful protesters in the West Bank. 3 Palestinian demonstrators were wounded in the demonstrations of Ni’lin and Bil’in, west of Ramallah. 5 Palestinian civilians, including a child, were wounded in a demonstration organized in solidarity with the Palestinian administrative detainees on hunger strike. Israeli forces conducted 76 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank. 28 Palestinian civilians, including 4 children and woman, were arrested. A Palestinian civilian was wounded when Israeli forces moved into al-‘Arroub refugee camp, north of Hebron. Israel has continued its efforts to create a Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem Israeli forces raided the Pal Media office and arrested two of its workers and a guest of “Good Morning Jerusalem” program. Israel continued to impose a total closure on the oPt and has isolated the Gaza Strip from the outside world. Israeli forces established dozens of checkpoints in the West Bank. -

Public Perceptions and Knowledge Towards Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture in Deir Debwan

First Symposium on Wastewater Reclamation and Reuse for Water Demand Management in Palestine, 2-3 April 2008, Birzeit University, Palestine Public Perceptions and Knowledge towards Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture in Deir Debwan Maher Abu-Madi*, Ziad Mimi*, and Niveen Abu-Rmeileh** *Institute of Environmental and Water Studies, Birzeit University, Palestine E-mail: [email protected] **Institute of Community and Public Health, Birzeit University, Palestine Abstract The Occupied Palestinian Territory is facing a rapid population growth with limited water resources. The continuous demand for water forces Palestinians to look for alternative water recourses. Wastewater reuse in agriculture is one of the strategic alternatives. A cross sectional survey took place in one of Ramallah villages to investigate people’s perception toward wastewater reuse in agriculture in 2007. Over all, participants had good knowledge about the general water crisis, 93 % were aware of the water crisis in Palestine, and 90 % were aware of water crisis in their village. Interestingly, 73 % knew that there are negative impacts from using untreated wastewater in irrigation and 24% knew that there are negative impacts from using treated wastewater. Further, only 40 % knew that there are special standards for wastewater reuse and 42 % did not know if there should be special standards for wastewater reuse. It was obvious that participants are willing to use treated wastewater (87 %) and products irrigated with it (85 %). However, the situation was opposite concerning untreated wastewater with only 6 % are willing to use it and 10 % are willing to use products irrigated with it. Health was the main reason followed by environmental and economical reasons for not accepting the reuse of wastewater. -

The Women's Affairs Technical Committees

The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ The Women’s Affairs Technical Committees Summary Report for the period of January 1st. 2010 - December 31st. 2010 1 The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ - Introduction - General Context o General Demographic Situation o Political Situation o Women lives within Patriarchy and Military Occupation - Narrative of WATC work during 2010 in summary - Annexes 1 and 2 2 The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ Introduction: This is a narrative summary report covering the period of January 2010 until 31 December 2010. The objective of this report is to give a general overview of the work during 2010 in summary and concise activities. At the same time, there have been other reports presented for specific projects and programs. General Context: Following part of the summary report presents the context on which programs, projects and activities were implemented during 2010. Firstly, it gives a general view of some demographic statistics. Secondly, it presents a brief political overview of the situation, and thirdly it briefly presents briefly some of the main actors that affected the life of Palestinian women during 2010. General Demographic situation: Data from the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) shows that the population of the Palestinian Territory is young; the percentage of individuals in the age group (0- 14) was 41.3% of the total population in the Palestinian Territory at end year of 2010, of which 39.4% in the West Bank and 44.4% in Gaza Strip. As for the elderly population aged (65 years and over) was 3.0% of the total population in Palestinian Territory at end year of 2010.