05-04-2019 Rigoletto Mat.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATTHEW POLENZANI, Tenor

CNDM | XXVII CICLO DE LIED M. POLENZANI & J. DRAKE · 20/21 MATTHEW POLENZANI, tenor El tenor estadounidense Matthew Polenzani es uno de los tenores líricos más talentosos y distinguidos de su generación. Su elegante maestría musical, sentido innato estilístico y compromiso dramático han permitido su continua presencia en los principales teatros de ópera, conciertos y recitales de todo el mundo. La temporada de otoño de 2020 de Polenzani comienza con una interpretación en versión de concierto de la ópera Attila de Verdi en la Lyric Opera of Chicago, seguido de un recital de Lied con Julius Drake en el Teatro de la Zarzuela, y la Missa Solemnis de Beethoven con la Filarmónica de Münchner. En 2021, Polenzani regresará a la Lyric Opera of Chicago como Nemorino en L'elisir d'amore de Donizetti y a la Royal Opera House como Don Jose en Carmen de Bizet. Concluirá la temporada cantando el papel principal de Idomeneo de Mozart y actuando de nuevo junto a Julius Drake en un recital en la Bayerische Staatsoper. En la temporada 2019/20, Polenzani protagonizó tres producciones en el Metropolitan Opera: Macbeth (Macduff), La Bohème (Rodolfo) y Der Rosenkavalier (El cantante italiano). Para la gala de Nochevieja del Met, cantó el primer acto de La Bohème junto a Anna Netrebko. También volvió a la Bayerische Staatsoper para cantar Don José en Carmen. Las siguientes actuaciones fueron canceladas debido a la pandemia: Missa Solemnis y Fidelio de Beethoven, que habrían marcado su debut en el papel como Florestan, ambas en el Festspielhaus de Baden-Baden; dos recitales con Julius Drake; y una clase magistral en la Northwestern University. -

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

01-25-2020 Boheme Eve.Indd

GIACOMO PUCCINI la bohème conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Franco Zeffirelli Luigi Illica, based on the novel Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger set designer Franco Zeffirelli Saturday, January 25, 2020 costume designer 8:00–11:05 PM Peter J. Hall lighting designer Gil Wechsler revival stage director Gregory Keller The production of La Bohème was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington Revival a gift of Rolex general manager Peter Gelb This season’s performances of La Bohème jeanette lerman-neubauer and Turandot are dedicated to the memory music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin of Franco Zeffirelli. 2019–20 SEASON The 1,344th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S la bohème conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance marcello muset ta Artur Ruciński Susanna Phillips rodolfo a customhouse serge ant Roberto Alagna Joseph Turi colline a customhouse officer Christian Van Horn Edward Hanlon schaunard Elliot Madore* benoit Donald Maxwell mimì Maria Agresta Tonight’s performances of parpignol the roles of Mimì Gregory Warren and Rodolfo are underwritten by the alcindoro Jan Shrem and Donald Maxwell Maria Manetti Shrem Great Singers Fund. Saturday, January 25, 2020, 8:00–11:05PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Roberto Alagna as Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Rodolfo and Maria Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Joshua Greene, Agresta as Mimì in Jonathan C. Kelly, and Patrick Furrer Puccini’s La Bohème Assistant Stage Directors Mirabelle Ordinaire and J. Knighten Smit Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Joseph Lawson Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Associate Designer David Reppa Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ladies millinery by Reggie G. -

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

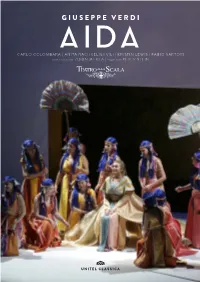

Giuseppe Verdi

GIUSEPPE VERDI CARLO COLOMBARAAIDA | ANITA RACHVELISHVILI | KRISTIN LEWIS | FABIO SARTORI CONDUCTED BY ZUBIN MEHTA | STAGED BY PETER STEIN GIUSEPPE VERDI Giuseppe Verdi’s masterpiece AIDA at La Scala in Milan is an experience in itself. Consequently, a new production of AIDA is an event barely to be surpassed, especially when performed before a notoriously critical audience of la La Scala. AIDA With his unpretentious and lucid new interpretation of the opera, directorial legend Peter Stein succeeds in delivering a production acclaimed in equal measure by the Orchestra Orchestra and Chorus press and public: “a perfect coup de theatre” (Giornale della musica). of the Teatro alla Scala Conductor Zubin Mehta Indeed, he breathes new life into Giuseppe Verdi’s romantic drama about power, Stage Director Peter Stein passion, jealousy and death: the Nubian Princess Aida, who is unfortunate enough to find herself in prison in Egypt, is secretly in love with the leader of the army, The King Carlo Colombara Radamès. He however has been promised in marriage to the Egyptian king's Amneris Anita Rachvelishvili daughter Amneris, who also loves him. The secret love affair between Aida and Aida Kristin Lewis Radamès is uncovered and fate takes its course ... Radamès Fabio Sartori A “stellar cast” (La Stampa) contributes to the production’s success Ramfis Matti Salminen under the musical direction of Verdi specialist Zubin Mehta. Amonasro George Gagnidze “The entire ensemble is brilliant in its portrayal of the A Messenger Azer Rza-Zada characters” (Die Presse), especially the American soprano The High Priestess Chiara Isotton Kristin Lewis in the title role. -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Star Singers on Stage

STAR SINGERS ON STAGE CONCERT TOUR 2017/18 CREATING AND MANAGING PRODUCTIONS WORLDWIDE GuliAnd Management is dedicated to all aspects of music performances from concerts to fully staged opera and operetta productions, special events, tours, broadcasts. The founders and partners of GuliAnd have been working together for many years. We have extensive international business network for the sake of successful productions. Our company is one of the most well-known producers of opera events with the new opera star generation in the industry. GuliAnd sets up and promotes individual concerts in theatres, arenas, stadiums and open air venues. In addition, we produce television programs as well as documentaries. It has been our great pleasure to present many colourful events with numerous internationally acknowledged artists in the past years. The PÉCS – PLÁCIDO DOMINGO CLASSICS festival was founded by the city of Pécs and GuliAnd Management in 2017. GuliAnd is registered in the United Kingdom and has an affiliated company in the United States as well as in Hungary. PÉCS2010 EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE GuliAnd Management introduced a new tradition with the “Voices” in 2009. Photo© Kaori Suzuki PLÁCIDO DOMINGO’S OPERALIA THE WORLD OPERA COMPETITION hosted by the Astana Opera within the framework of the EXPO-2017 Future Energy programme and under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of kazakhstan, the 25th edition of the World Opera Competition, including its final, was one of the highlights of Astana’s cultural calendar this summer, held from 24-29 July. ARYSTANBEK MUKHAMEDIULY Minister of Culture and Sports of Kazakhstan BIG STANDING OVATIONS GuliAnd presents this regular events with Plácido Domingo’s Operalia, The World Opera Competition award winning singers at the United Kingdom, Austria, Hungary and Germany. -

Child of God CD Credits & Bios

Photo Credit: “Icelandic Bower” Deborah Offenhauser © 2015 The voice of Isola Jones brings forth glorious praise in Deborah’s inspirational songs, backed by orchestral arrangements that bring out every nuance of God’s love and healing for each “Child of God”. To those“sincere seekers” I dedicate this album. Deborah Opening Credits CHILD OF GOD CD Cover and Digi-Book Design by Deborah Offenhauser Photographs by Deborah Offenhauser “Icelandic Yellow Flowers” © 2015 Lloyd Shaffer Lloyd Shaffer and Susan Shaffer Nahmias Original Apple and Bottle Paintings by Lloyd Shaffer, Phoenix, Arizona Recording Studio: Opus Fromus, Phoenix, Arizona Sound Engineers: Tim Ponzek and Lisa Pressman CD Mastered by Dave Shirk of Sonorous Mastering, Phoenix, Arizona All songs copyrighted by Deborah Offenhauser Vocal Artistry: Isola Jones Piano Performance, Arrangements and Orchestrations by Deborah Offenhauser Acknowledgments and Credits Co-Producers: Tim Ponzek, Lisa Pressman and Deborah Offenhauer To Tim: Wow! Your willingness to sit for those long sessions in the recording studio is nothing short of amazing. What an engineer! To Lisa: Your indefatigable ears and counsel along this winding road have been so appreciated! You are stellar! To Isola: Thank you so much, dear one, for your long hours and patience in learning the material, and then rehearsing and putting those finishing touches on each recording! To Barb: Hasn’t this been a lovely trip together? Thanks for your healing lyrics. To Lloyd: Dear hubby mine – you’ve been so stalwart in spending long hours alone while I composed, and then arranged, edited, orchestrated and recorded this album over the course of a year. -

National-Council-Auditions-Grand-Finals-Concert.Pdf

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Bertrand de Billy National Council Auditions host and guest artist Grand Finals Concert Joyce DiDonato Sunday, April 29, 2018 guest artist 3:00 PM Bryan Hymel Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2017–18 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Bertrand de Billy host and guest artist Joyce DiDonato guest artist Bryan Hymel “Martern aller Arten” from Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Mozart) Emily Misch, Soprano “Tacea la notte placida ... Di tale amor” from Il Trovatore (Verdi) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Va! laisse couler mes larmes” from Werther (Massenet) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Cruda sorte!” from L’Italiana in Algeri (Rossini) Hongni Wu, Mezzo-Soprano “In quali eccessi ... Mi tradì” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Today’s concert is Danielle Beckvermit, Soprano being recorded for “Amour, viens rendre à mon âme” from future broadcast Orphée et Eurydice (Gluck) over many public Ashley Dixon, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Gualtier Maldè! ... Caro nome” from Rigoletto (Verdi) local listings. Madison Leonard, Soprano Sunday, April 29, 2018, 3:00PM “O ma lyre immortelle” from Sapho (Gounod) Gretchen Krupp, Mezzo-Soprano “Sì, ritrovarla io giuro” from La Cenerentola (Rossini) Carlos Enrique Santelli, Tenor Intermission “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Down you go” (Controller’s Aria) from Flight (Jonathan Dove) Emily Misch, Soprano “Sein wir wieder gut” from Ariadne auf Naxos (R. Strauss) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Wie du warst! Wie du bist!” from Der Rosenkavalier (R. -

Join Us for Placido Domingo and Company in New York City April 7-10, 2016

Join Us for Placido Domingo and Company in New York City April 7-10, 2016 The ageless Placido Domingo is continuing his remark- able career by performing classic roles of the baritone rep- ertoire, and the Metropolitan Opera in April is offering one of his greatest baritone roles, the title role in Verdi's drama Simon Boccanegra. The Met is pairing it with Donizetti's bel canto classic Roberto De- vereux (a story of Queen Elizabeth I of England) starring two of today's greatest divas, the soprano Sondra Radvanovsky and the mezzo soprano Elīna Garanča. To top it off, the Metropolitan Opera is performing in the same week the delightful comedy L'Elisir d'Amore (The Elixir of Love). It was a lineup we just couldn't resist, so please join our tour guide Wilma Wilcox in New York in April. Here is our plan: Thursday, April 7, 2016. We leave from Kansas City and fly nonstop to New York, ar- riving in time for dinner at our favorite Lincoln Cen- ter-area restaurant, Gabri- el's, before heading to the Metropolitan Opera for Donizetti's delightful com- edy L'Elisir d'Amore (The Elixir of Love). Starring in the cast are the sparkling Polish soprano Aleksan- dra Kurzak, tenor Mario Chang, Czech baritione Adam Plachetka and the comic Italian bass Pietro Spagnoli. Soprano Sondra Radvanovsky (upper Friday, April 8, 2016. left) and mezzo soprano Elīna Garanča (left) star in the Donizetti classic Roberto This day is free for you to Devereux, a story of Queen Elizabeth I explore the sights of New of England.