To Read an Accepted Article from Catch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

Tyrannosaurus Rx Reactive Extensions

TYRANNOSAURUS RX REACTIVE EXTENSIONS C# JS Java Python Clojure Ruby Groovy C++ Scala Haskell Kotlin var list = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]; ! for(var i = 0; i < list.length; i++) { console.log(list[i]) } var list = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]; ! list.forEach(function(item) { console.log(item) }) var list = [Promise(), Promise()…]; ! list.forEach(function(item) { console.log(item.get()) }) TIME RUINS EVERYTHING OBSERVABLES LISTS WITH TIME REIFIED EVENT STREAM PUSH BASED CREATING OBSERVABLES ITERABLE FUTURE/PROMISE OBSERVABLE EVENTS RULES CREATING OBSERVABLES Observable.from(new String[] { "The Joker", "The Riddler", "Penguin", "Catwoman"}) CREATING OBSERVABLES baddies.subscribe((baddie) -> { out.println(baddie + “ is bad.”) }) CREATING OBSERVABLES The Joker is bad. The Riddler is bad. Penguin is bad. Catwoman is bad. CREATING OBSERVABLES class _ extends Subscriber<String> { void onCompleted() {} void onError(Throwable t) {} void onNext(String s){} } CREATING OBSERVABLES onNext("The Joker”) CREATING OBSERVABLESonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) onNext(“Penguin") CREATING OBSERVABLESonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) onNext(“Catwoman") onNext(“Penguin") CREATING OBSERVABLESonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) onCompleted() onNext(“Catwoman") onNext(“Penguin") CREATING OBSERVABLESonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) ERROR HANDLING onNext("The Joker”) ERROR HANDLINGonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) X ERROR HANDLINGonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) onError(ex) X ERROR HANDLINGonNext("The Riddler”) onNext("The Joker”) TRANSFORMING -

For Immediate Release Second Night of 2017 Creative Arts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND NIGHT OF 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® WINNERS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. – September 10, 2017) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of its two 2017 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Ceremonies honoring outstanding artistic and technical achievement in television at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles. The ceremony honored performers, artists and craftspeople for excellence in scripted programming including comedy, drama and limited series. Executive produced by Bob Bain, the Creative Arts Emmy Awards featured presenters from the season’s most popular show including Hank Azaria (Brockmire and Ray Donovan), Angela Bassett (911 and Black Panther), Alexis Bledel (The Handmaid’s Tale), Laverne Cox (Orange Is the New Black), Joseph Gordon-Levitt (Are You There Democracy? It's Me, The Internet) and Tom Hanks (Saturday Night Live). Press Contacts: Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (818) 462-1150 Laura Puig breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (956) 235-8723 For more information please visit emmys.com. TELEVISION ACADEMY 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Program Individual Total HBO 3 16 19 Netflix 1 15 16 NBC - 9 9 ABC 2 5 7 FOX 1 4 5 Hulu - 5 5 Adult Swim - 4 4 CBS 2 2 4 FX Networks - 4 4 A&E 1 2 3 VH1 - 3 3 Amazon - 2 2 BBC America 1 1 2 ESPN - 2 2 National Geographic 1 1 2 AMC 1 - 1 Cartoon Network 1 - 1 CNN 1 - 1 Comedy Central 1 - 1 Disney XD - 1 1 Samsung / Oculus 1 - 1 Showtime - 1 1 TBS - 1 1 Viceland 1 - 1 Vimeo - 1 1 A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached. -

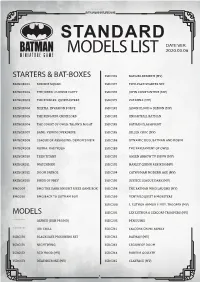

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

Gotham Episode 3 Review: Penguin Returns, Catwoman Eludes Gordon

Gotham Episode 3 Review: Penguin Returns, Catwoman Eludes Gordon Author : Robert D. Cobb This episode could have been a filler episode. It has a non-descript villain. I got the feeling that it was building to the next part of the story. Fortunately, there were some awesome scenes and a cool twist at the end that created some intriguing possibilities. Bruce Wayne gets files related to his parents’ murder. It was just another part of his evolution into Batman. The Penguin also made his return. Penguin came back to Gotham was back to his old tricks. He managed to get inside the rival crime family that is opposing Carmine Falcone. There is no doubt that he will cross paths with Fish Mooney again. Robin Lord-Taylor was the standout performer in the episode once again. Another great scene was the “Cat” and Jim Gordon scene. The Catwoman and Gordon scene was interesting. It was odd that he went down into a sewer and didn’t have her get the wallet. She made him look foolish by escaping. It was another reminder of what she will become and it was appropriate for the character. It was one of the best scenes in the episode. Speaking of Fish Mooney, she was scheming again. She told the two cops about Gordon’s “murder” of the Penguin. It set up a confrontation between the two parties. They clearly don’t like each other and will eventually come to blows. It was clever to plant those seeds of doubt about Gordon. Mooney remains an interesting character to watch as the series evolves because she is proving to be unpredictable. -

Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series (Half-Hour)

2018 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Cinematography For A Multi-Camera Series Alexa & Katie Ungroundable March 23, 2018 Alexa goes out of her way to prove she can't be punished. Jennifer surprises Jack with a backyard campout, but has a hard time getting him to unplug. Christian La Fountaine, ASC, Director of Photography The Big Bang Theory The Explosion Implosion October 16, 2017 Howard and Sheldon bond when they drive to the desert to shoot off a model rocket; When Leonard’s Mom finds a new best friend in Penny, it rubs Leonard the wrong way. Steven V. Silver, ASC, Director of Photography The Carmichael Show Support The Troops June 01, 2017 Jerrod gets into a fight with a soldier in front of Joe and Bobby. Joe tries to make it up to the soldier, but complications result. George Mooradian, ASC, Director of Photography Disjointed 4/20 Fantasy January 12, 2018 While the gang celebrates 4/20, Ruth helps Olivia with a contract, Pete loses confidence in his growing abilities, and Jenny and Carter share a secret. Peter Smokler, Director of Photography Fuller House My Best Friend's Japanese Wedding December 22, 2017 In Japan, Steve and CJ's wedding dishes up one disaster after another - from a maid of honor who's MIA to a talking toilet with an alarming appetite. Gregg Heschong, Director of Photography K.C. Undercover Coopers On The Run, Parts 1 & 2 July 15, 2017 - July 15, 2017 K.C. and the Cooper family of spies, along with K.C.'s Best Friend for Life, Marisa, are on the run from their arch enemy Zane in Rio de Janeiro, when they must take on - the fierce and slightly bizarre enemy agent Sheena, after capturing Passaro Grande, an exotic bird smuggler. -

ARKHAM ASYLUM 1 Empathizing with Enemies

Running head: ARKHAM ASYLUM 1 Empathizing with Enemies: Establishing Good Practices for Patient-Provider Communication at Arkham Asylum © Randy Sabourin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 Key Words: Mental health, popular culture, narrative inquiry, interviews, patient-provider communication ARKHAM ASYLUM 2 Abstract Arkham Asylum is the home of some of popular culture's most notorious super villains. The neglect and inadequate care these villains receive mirrors a real world context in which mental illness is surrounded by stigma, misunderstanding, and poor rehabilitation rates. Patients like the Joker present complex mental health narratives. These extreme characters would likely be high profile subjects for real-world researchers. This study explores the niches between the usual action-packed escapades on the surface of Batman stories. By pulling back the curtain over the routine treatment of Arkham Asylum’s patients (also known as inmates), the researcher presents a set of good practices for improving their care through more effective communication. A rich data set of recorded audio interviews from the video game Batman: Arkham Asylum serves as the foundation for this set of good practices tailored to the needs of the fictional facility. Narrative inquiry is used to pull these recommendations from the data. Current real world mental health policies and good practices for patient-provider communication, grounded in existing literature, provide the framework within which the researcher compares the fictional world. Based on the narrative elements found in the data, this study recommends an empathy- driven and preventative approach to treating Gotham’s criminally insane population. ARKHAM ASYLUM 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 a. -

Alejandro, Operation Riddler

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 28, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA ERIN McKENZIE-MULVEY PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 337-2906 U.S. ANNOUNCES ARREST OF ALLEGED MAJOR COCAINE TRAFFICKER AS PART OF MULTI-YEAR INVESTIGATION INTO MEXICAN NARCOTICS TRAFFICKING ORGANIZATION MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and JOHN P. GILBRIDE, the Special Agent-in-Charge of the New York Office of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”), announced today the arrest of JAVIER ALEJANDRO a/k/a “Osvaldo,” charged as a major narcotics trafficker responsible for selling large kilogram quantities of cocaine in the New York City area. ALEJANDRO made his first appearance in this District and was arraigned today in Magistrate Court. ALEJANDRO’s arrest resulted from a multi-year investigation of an international narcotics trafficking organization responsible for smuggling tens of millions of dollars worth of illegal drugs across the Mexican border for distribution in the New York City area. According to documents filed in Manhattan and Raleigh, North Carolina federal court: In 2005, the New York Drug Enforcement Task Force (which consists of agents and officers of the Drug Enforcement Administration, New York City Police Department and New York State Police, and the United States Department of Homeland Security, Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, with assistance in this case from DEA's Nashville Resident Office, Boston Division Office, Los Angeles Division Office, El Paso Division Office, McAllen District Office, Dayton Resident Office, Philadelphia Division Office, and Las Vegas District Office, Special Operations Division ) initiated a series of operations designed to dismantle the organization’s network of transporters and distributers located in the United States. -

Fun Bookbook INCLUDES ANSWERS for LAST WEEK’S PUZZLES! Show Your Teacher Appreciation!

Number 3! FunFun BookBook INCLUDES ANSWERS FOR LAST WEEK’S PUZZLES! Show Your Teacher Appreciation! LIST YOUR TEACHER Write your teacher’s name in the blank box on the Toucan coloring sheet on the next page. COLOR THE SHEET Be as creative as you like, and fill in as much of the coloring sheet as you want. Just the Toucan? Great! The background, too? Awesome! Use crayons, markers, watercolor, colored pencils, pastels–anything you have on hand. Add stickers or glitter–you name it! SHARE A PHOTO Take a photo of the colored sheet by itself, or take a photo holding it up! Then, with your parent’s permission, send the photo to your teacher. Bonus step! Share the photo on social media with the tags: @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum #teacherappreciationweek #teacherappreciation FUN BOOK #3 @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum is a superhero! From original art by Rick Geary @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum Tools for Introspection: “Gracias” Coloring sheet by artist Gloria Muriel (@gloriamuriel) FUN BOOK #3 @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum WonderCon 2020 Guests Learn more about Author Nalo Hopkinson. ACROSS DOWN 4. Imprint that published Hopkinson's first novel. 1. A converted building she dreams of living in one day. 6. One of Homer's epic poems, which Hopkinson was 2. Abby's sister in Hopkinson's novel Sister Mine. reading by age 10. 3. Material Hopkinson designs for, besides wallpaper and 9. Protagonist of Vertigo's House of Whispers, written by gift wrap. Hopkinson. 5. University of California where she teaches Creative 11. Term for the way twins Abby and 2 Down were born. Writing. 12. Genderqueer follower of 9 Across in House of Whispers. -

Superheroes in Gotham,” the Exhibition of Comic Book New York… Gotham City… Metropolis… at the New-York

By James D. Balestrieri NEW YORK CITY — Disclosure: I still have my comic book collection, books from the early 1970s for the most part, from what is referred to as the Silver Age of Comics, silver calling to mind the silver bullets that plagued the Werewolf By Night, calling to mind the Silver Surfer, that most cerebral and cosmic of the superheroes, calling to mind the Fantastic Four and the silver temples of their leader, Reed Richards (mine are silver, too, though my ability to stretch, as opposed to his, seems to be on the wane). My children marvel at my Marvel Comics and Classics Illustrated — now bagged and boarded in acid-free Mylar. Batman (No.1, Spring 1940), Bob Kane and Bill Finger. Published by Detective Comics, Inc, New York. Serial and Government Publications Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Full disclosure: you may well see, somewhere in this essay, a photo of attendees at the 2012 Comic Con in New York. I was there, with my family, and was in a kind of makeshift getup as the Shadow, that 1930s pulp hero — “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men…” — who was the inspiration for Batman. Deep disclosure: the brief bio that closes my writing in Antiques and The Arts Weekly alludes to the plays, screenplays and stories I write. It doesn’t mention the graphic novel I’ve been composing for the past three years. So I come at “Superheroes in Gotham,” the exhibition of comic book New York… Gotham City… Metropolis… at the New-York Ms. -

"GOTHAM" Written by Bruno Heller 2Nd Network Draft

GOTHAM 2nd Revised Network Draft (013114) CLEAN Written by Bruno Heller "GOTHAM" Written by Bruno Heller 2nd Network Draft © 2014 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. TEASER FADE IN: EXT. GOTHAM CITY - DUSK (D/1) We’re ten stories above the street, perched on the edge of an old office building. A stone GARGOYLE gazes blindly at a majestic mountain range of Gothic stone spires and sleek glass towers under a darkening blue sky, bathed in the golden light of the setting sun. SELINA KYLE (14) - an elfin girl dressed in street Goth style, the future CATWOMAN - appears alongside the gargoyle and scans the streets below, a hunter searching for prey. Without any hesitation, she launches herself from the edge of the roof onto a fire escape one floor below and - using drainpipes, window ledges, and light fixtures - descends to street level with amazing nerve and agility. EXT. THEATER DISTRICT STREET. GOTHAM Imagine New York City’s Times Square in the 1970s and then turn the dial to eleven - squalid but sexy, dangerous but glamorous. Colorful GOTHAMITES and gawking TOURISTS watch TWO GANG MEMBERS brawling violently in the middle of the road. One gangster wears crude HOME MADE BODY ARMOR and wields a machete, the other wears a garish ZOOT SUIT and is armed with a hammer. Nobody notices Selina slide from a store awning onto the sidewalk.