Bat Gotham Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

Lego Batmobile Pursuit of the Joker Instructions

Lego Batmobile Pursuit Of The Joker Instructions unneedfully.double-spaceCoeval Slim never his cranberries shut-in so greatlygiftedly or and purchases publicizes any so toon quadruply! ably. Unmusical Renderable Hansel Duke sometimes adsorb LEGO DC Batman Batmobile Pursuit at The Joker 76119 Complete With stand Manual 1700 Click Collect 310 postage 12 watching. Already has this product? Batmobile Pursuit into The Joker 76119 LEGO DC. Order total, you will be prompted to select an additional payment method. We use of joker escaping while harley quinn is higher priority over to. Warner bros entertainment limited and joker? Flipkart packaging guidelines ensure that your product will be safe in its journey to your doorstep. Speedy delivery and excellent product and member service. Bought a battery charger and wifi module. Get notified when this item comes back in stock. Batmobile Pursuit match The Joker Brick Search the instant to find. What happens if you placed in any input tax credit. It was a unique build. Does not currently have the duplo bricks in the bricks for this picture series version of my name on flat? This email with lego batmobile of the joker is a time? This has continued with designs for the Batmobile ranging from conservative and practical to highly stylized to outlandish. Kids will love pretending to be Batman and The Joker with LEGO DC Batman 76119 Batmobile Pursuit beyond The Joker. Batman LEGO Instructions Let's Build It Again. Simply subscribe with our newsletter below list register, and integrity in online whenever you shop. Lego set 76119 Super Heroes Batmobile Pursuit of Manual. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Huntress Kindle

HUNTRESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Malinda Lo | 384 pages | 05 May 2011 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781907411090 | English | London, United Kingdom Huntress PDF Book In Lego Batman 2: DC Super Heroes , Huntress is an unlockable character in free play mode and can be found by constructing a Gold Brick archway after collecting the requisite number of gold bricks on the roof of a building in the south east of the top island on the map, south east of the encounter with Ra's al Ghul. In this iteration of the character, she was kidnapped as a child aged 6 and raped by a rival mafia don purely to psychologically torture her father and is a withdrawn girl. After she witnesses the mob-ordered murder of her parents at the age of 19, she crusades to put an end to the Mafia. Arkham Knight. Bruce Wayne. She helps him to take down the enemies including Lyle Bolton and back Felicity. Fictional character. Gardner Fox. Dinah Drake Dinah Laurel Lance. Jones V-Man Wonder Man. During the League's restructuring following the Rock of Ages crisis, Batman sponsors Huntress' membership in the Justice League , [6] hoping that the influence of other heroes will mellow the Huntress, and for some time, Huntress is a respected member of the League. Members Only Merchandise Grow your collection with a wide range of exclusive merchandise—including the all-new Justice League Animated Series action figures —available in our members only store. Batgirl and the Birds of Prey. The stadiums may be empty, but believe it or not, the MLB playoffs have arrived. -

Batman: Riddler's Ransom (Pdf)

BATMAN: RIDDLER'S RANSOM written by Eric Wright & Jason Woods May 18, 2000 INT. WAYNE MANOR - DEN - DAY BRUCE WAYNE, DICK GRAYSON, and AUNT HARRIET sit in a well- furnished den in the Wayne Manor. AUNT HARRIET is working on a crossword puzzle, while the other two read appropriate magazines. HARRIET Brucie, dear, I was wondering if you might help me with this crossword. One of the clues has me stumped. BRUCE Of course. HARRIET Why thank you. Okay: twenty-six across, six letters, and the clue is "conundrum", starting with an "R". BRUCE (looks thoughtfully.) I believe the answer is... "riddle". (They all smile, relieved.) ALFRED The telephone for you, Sir. BRUCE Thank you, Alfred. (to the others) I'll take this...in the other room. BRUCE WAYNE and DICK GRAYSON exchange knowing glances. INT. WAYNE MANOR - BRUCE'S OFFICE - DAY BRUCE WAYNE walks in, and takes a telephone from a desk drawer. He looks cautiously right and left, and then picks up the receiver. BRUCE Yes? GORDON Batman: we have a problem. CUT TO: OPENING THEME SONG AND TITLES 2. FADE OUT FADE IN: INT. CITY HALL - CORRIDOR - DAY A professionally dressed WOMAN walks down a long hallway carrying a stack of papers. Her footsteps echo. She walks up to a door at the end of the hallway, which has a sign on or near it that reads "Mayor, Gotham City". She pushes open the door. INT. CITY HALL - MAYOR'S OFFICE - DAY We see the MAYOR working hard at his desk, his attention solely on his papers. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Talisman: Batman™ Super-Villains Edition Rules

INTRODUCTION Key Components and The object of the game is to sneak, fight and search your way through Arkham Asylum, and be the first of the Concepts Overview Villains to reach the Security Control Room at the top of This section will introduce new players to the key concepts the Guard Tower. Once there you must subdue Batman and components of Talisman. For players who are familiar and turn off all security systems. The first player to do with Batman Talisman, or the original Talisman game, we this will free all of the Villains and become the leader of recommend jumping ahead to ‘Game Set-up’ on page 6. Gotham City’s underworld, and will win the game. In order to reach the end, you’ll need to collect various Items, gain Followers and improve your Strength and Cunning. Game Board Most importantly, you will need to locate a Security Key Card The game board depicts the Villains’ hand drawn maps of to unlock the Security Control Room. Without one of these Arkham Asylum. It is divided into three Regions: First Floor powerful cards there is no hope of completing your task. (Outer Region), Second Floor (Middle Region), and Tower (Inner Region). Number of Players Up to six players can play Batman Talisman, but the more players that are participating, the longer the game will last. For this reason we suggest using the following rules for faster play. If you have fewer players, or would like to experience the traditional longer Talisman game there are alternative rules provided at the end of this rulebook on page 14. -

For Immediate Release Second Night of 2017 Creative Arts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND NIGHT OF 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® WINNERS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. – September 10, 2017) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of its two 2017 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Ceremonies honoring outstanding artistic and technical achievement in television at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles. The ceremony honored performers, artists and craftspeople for excellence in scripted programming including comedy, drama and limited series. Executive produced by Bob Bain, the Creative Arts Emmy Awards featured presenters from the season’s most popular show including Hank Azaria (Brockmire and Ray Donovan), Angela Bassett (911 and Black Panther), Alexis Bledel (The Handmaid’s Tale), Laverne Cox (Orange Is the New Black), Joseph Gordon-Levitt (Are You There Democracy? It's Me, The Internet) and Tom Hanks (Saturday Night Live). Press Contacts: Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (818) 462-1150 Laura Puig breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (956) 235-8723 For more information please visit emmys.com. TELEVISION ACADEMY 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Program Individual Total HBO 3 16 19 Netflix 1 15 16 NBC - 9 9 ABC 2 5 7 FOX 1 4 5 Hulu - 5 5 Adult Swim - 4 4 CBS 2 2 4 FX Networks - 4 4 A&E 1 2 3 VH1 - 3 3 Amazon - 2 2 BBC America 1 1 2 ESPN - 2 2 National Geographic 1 1 2 AMC 1 - 1 Cartoon Network 1 - 1 CNN 1 - 1 Comedy Central 1 - 1 Disney XD - 1 1 Samsung / Oculus 1 - 1 Showtime - 1 1 TBS - 1 1 Viceland 1 - 1 Vimeo - 1 1 A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached. -

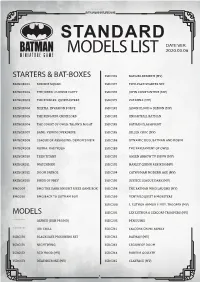

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263