Vindication of Celtic Inscriptions on Gaulish And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Rare and Unpublished Ancient British Coins

AN ACCOUNT OF SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS, COMMUNICATED TO THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON BY JOHN EVANS, F.S.A., F.G.S., HON. SEC. NUM.SOC. LONDON: 1860. 1·~~~ ANCIENT BRITISH COi NS. AN ACCOUNT or SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS, COMMUNICATED TO THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON BY JOHN EVANS, F.S. .A., F.G.S., BON. SBC. NUM. SOC. LONDON: 1860. Stack Annex !:>01.5346 SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS. Read before the Numismatic Society, Jan. 26th, 1860.] r HAVE again the satisfaction of presenting to the Society a plate of ancient British coins, most ofof them hithetto un- published, and all of the highest degree of rarity. Unlike the last miscellaneous plate of these coins that I , drew, which consisted entirely of uninscrihed coins, these areall i11scribed, and comprise Specimens of the coinage of Cuno beline, Taseiovanus, Dubnovellaunus, and the Iceni, beside others of rather more doubtful attribution. l need not, however, make any prefatory remarks conceming them, hut will at once proceed to the description of the various coins, and the considerations which arc suggested by thei1· several types and inscriptions. T'he first three are of Cunobeline. No. 1. Obv. - CA-MVon either side of an ear of bearded corn, as usual on the gold coins of Cunobeline, hut rather more widely spread. The stalk terminating in an ornament shaped like Gothic trefoil. Rev.-CVNO beneath a horse, galloping, to the left; ahove, an ornament, in shape like the Prince of Wales' plume, resting on a reversed crescent. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

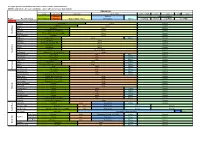

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Caratacus Errata

Caratacus Module Errata & Clarifications February, 2008 Components Counters There are 60 counters provided with the module. Corrections and additions to the counters include: •• The Briton MI should be BI instead •• Togudumnus counter is missing. Use any TC from Caesar/Gaul substituting the following ratings: Order/Line Range is 4/7; Initiative is 4; Charisma is 2 •• Cnaeus Sentius (commander of the Batavians) should have the following ratings: Command Range is 3; Initiative is 3; Line Command is 1; Charisma is 1; Strategy is 6. He is not a Cavalry commander, but the leader of the Batavians. The Briton army contains the following units: •• 2 Overall Commanders (Caratacus and Togodumnus) •• 3 Subordinate commanders (Taximagulus, Cingetorix, and Segovax chiefs of the Trinovantes, Atrebates and Cantii, respectively) •• 30 LI with 30 CH •• 20 BI (the MI counters) •• 4 LC Not all of the counters included in the module are used in the battles. There are 8 extra Briton BI (masquerading as MI, to be sure). Please use only 20 of these (you could always use the extras to alter play balance. Better more than too few). There is an extra Briton LI and CH, although including them is not exactly going to alter the game to any great extent. The extra CH counters are used for the extra Brit LI, which always used chariots to get around town. Since the original publication of the module, GMT has added 40 counters. This set includes: •• 20 Briton BI to replace the 20 Briton MI from the original counter set •• Togodumnus •• Cn. Sentius (ignore the Cav designation on the counter) •• 4 Batavian MI and 2 Batavian LI •• 12 Testudo/Harass & Disperse Markers Applicable Errata for Caesar: Conquest of Gaul Ignore this section when using the Caesar: Conquest of Gaul 2nd Edition rules. -

Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello

Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference Volume 11 Article 4 2020 Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello David Summers Capital University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Summers, David (2020) "Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello," Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference: Vol. 11 , Article 4. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc/vol11/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Literary Magazines at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello David Summers, Capital University etting to know the world through personal travel, particularly by means of the “semester abroad,” seems to G me to be one of the least controversial planks in the Humanities professors’ manifesto. However, reading Shakespeare with an eye toward determining his attitude toward travel creates a disjuncture between our conviction that travel generally, and studying abroad in particular, is an enriching experience, and Shakespeare’s tendency to hold the benefits of travel suspect. -

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

Art. IIL—The PEOPLES of ANCIENT SCOTLAND

(60) Art. IIL—the PEOPLES OF ANCIENT SCOTLAND. Being the Fourth Rhind Lecture. this lecture it is proposed to make an attempt to under- IN stand the position of the chief peoples beyond the Forth at the dawn of the history of this country, and to follow that down sketchil}' to the organization of the kingdom of Alban. This last part of the task is not undertaken for its own sake, or for the sake of writing on the history of Scotland, which has been so ably handled by Dr. Skene and other historians, of whom you are justly proud, but for the sake of obtaining a comprehensive view of the facts which that history offers as the means of elucidating tlie previous state of things. The initial difficulty is to discover just a few fixed points for our triangulation so to say. This is especially hard to do on the ground of history, so I would try first the geography of the here obtain as our data the situation country ; and we of the river Clyde and the Firth of Forth, then that of the Grampian ]\Iountains and the Mounth or the high lands, extending across the country from Ben Nevis towards Aberdeen. Coming now more to historical data, one may mention, as a fairly well- defined fact, the position of the Koman vallum between the Firth of Forth and the Clyde, coinciding probably with the line of forts erected there in the 81 it by Agricola year ; and is probably the construction of this vallum that is to be understood by the statements relative to Severus building a wall across the island. -

Histoire Des Collections Numismatiques Et Des Institutions Vouées À La Numismatique

25 Histoire des collections numismatiques et des institutions vouÉes À la numismatique Igor Van den Vonder and Guido Creemers tHe COINs AND MEDALs COLLECTION oF tHe GALLO-ROMAN MUSEUM IN TONGEREN (BELGIUM) the coin and medal collection of the Gallo-roman museum in tongeren is the former coin and medal cabinet (Munt- en Penningkabinet) of the Province of limburg. it is an important collection, comprising over 30,000 coins and exonumia. the collection reflects the coins produced and in circulation in the region from antiquity to the 19th century and is unique because many were excavated locally. When the coin and medal cabinet was established in 1985, the province’s own collection consisted of the collections belonging to the royal limburg Historical and antiquarian society (Koninklijk Limburgs Geschied- en Oud- heidkundig Genootschap) and the barons Philippe de schaetzen and armand de schaetzen de schaetzenhoff. these form the core of the collection, to- gether with the collection of the former small seminary of sint-truiden, on loan from the diocese of Hasselt. With the acquisition of several private collections, the coin and medal cabinet achieved its target of 10,000 items. an active collecting policy was implemented and the collection soon doubled in size, largely thanks to gifts. Furthermore, Belgium’s royal court made over Prince charles’ personal collection to the coin and medal cabinet as a long-term loan. systematic efforts were also made to acquire the coin hoards found in the region. at the end of the last century the Province of limburg decided to fully integrate the coin and medal cabinet into the archaeological collection of the Gallo-roman museum. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

The Gallic War - Book Iii (56 Bc)

JULIUS CAESAR (GAIUS JULIUS CAESAR, 100-44 BC) THE GALLIC WAR - BOOK III (56 BC) TRANSLATED BY W.A. MCDEVITTE AND W.S. BOHN ________________________________________ DE BELLO GALLICO - LIBER TERTIUS § 3:1. When Caesar was setting out for Italy, he sent Servius Galba with the twelfth legion and part of the cavalry, against the Nantuates, the Veragri, and Seduni, who extend from the territories of the Allobroges, and the lake of Geneva, and the River Rhone to the top of the Alps. The reason for sending him was, that he desired that the pass along the Alps, through which [the Roman] merchants had been accustomed to travel with great danger, and under great imposts, should be opened. He permitted him, if he thought it necessary, to station the legion in these places, for the purpose of wintering. Galba having fought some successful battles and stormed several of their forts, upon embassadors being sent to him from all parts and hostages given and a peace concluded, determined to station two cohorts among the Nantuates, and to winter in person with the other cohorts of that legion in a village of the Veragri, which is called Octodurus; and this village being situated in a valley, with a small plain annexed to it, is bounded on all sides by very high mountains. As this village was divided into two parts by a river, he granted one part of it to the Gauls, and assigned the other, which had been left by them unoccupied, to the cohorts to winter in. He fortified this [latter] part with a rampart and a ditch. -

CHARLES FUSSELL: CYMBELINE CHARLES FUSSELL B

CHARLES FUSSELL: CYMBELINE CHARLES FUSSELL b. 1938 CYMBELINE: DRAMA AFTER SHAKESPEARE (1984, rev. 1996) CYMBELINE [1] I. Prelude 4:03 [2] II. Duet: Imogen and Posthumus 3:26 [3] III. Interlude 1:39 [4] IV. Aria: Iachimo 1:10 [5] V. Imogen 3:39 [6] VI. Scene with Arias: Iachimo 10:19 [7] VII. Interlude 2:14 [8] VIII. Scene: Cloten 1:21 [9] IX. Song: Cloten 3:22 [10] X. Recitative and Arioso: Imogen and Belarius 3:04 ALIANA DE LA GUARDIA soprano [11] XI. Duet, Dirge: Guiderius and Arviragus 3:58 MATTHEW DiBATTISTA tenor [12] XII. Battle with Victory March 4:05 DAVID SALSBERY FRY narrator [13] XIII. Scene: Ghosts (Mother and Sicilius) and Jupiter 5:17 [14] XIV. Duet: Imogen and Posthumus 3:07 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [15] XV. Finale: Soothsayer and Cymbeline 4:14 Gil Rose, conductor TOTAL 55:02 COMMENT By Charles Fussell The idea of a musical depiction of this work came as a result of seeing the Hartford Stage productions of Shakespeare. Their Cymbeline, directed by Mark Lamos (who later moved to opera), ended with an unforgettable scene between Imogen and her husband: “Why did you throw your wedded lady from you? Think that you are upon a rock and throw me again.” His reply, “Hang there like fruit, my soul, till the tree die.” This exchange touched me deeply and really convinced me to try some music for the songs that appear in the play as well as this beautiful expression of love. I noticed the familiar “Hark, hark the lark” was sung by the frightful Cloten.