Alexa, What Should We Do About Privacy? Protecting Privacy for Users of Voice-Activated Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journey of Teaching Henrik Ibsen's a Doll House to Play Analysis

“ONLY CONNECT”: A JOURNEY OF TEACHING HENRIK IBSEN’S A DOLL HOUSE TO PLAY ANALYSIS STUDENTS Dena Michelle Davis, B.F.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Andrew B. Harris, Major Professor Donald B. Grose, Committee Member and Dean of Libraries Timothy R. Wilson, Chair of the Department of Dance and Theatre Arts Sandra L. Terrell, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Davis, Dena Michelle, “Only Connect”: A Journey of Teaching Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House to Play Analysis Students. Master of Arts (Theatre), May 2004, 89 pp., bibliography, 14 titles. This work examines the author’s experience in teaching A Doll House by Henrik Ibsen to students in the course Play Analysis, THEA 2440, at the University of North Texas in the Fall 2003 and Spring 2004 semesters. Descriptions of the preparations, presentations, student responses, and the author’s self-evaluations and observations are included. Included as appendices are a history of Henrik Ibsen to the beginning of his work on A Doll House, a description of Laura Kieler, the young woman on whose life Ibsen based the lead character, and an analysis outline form that the students completed for the play as a requirement for the class. Copyright 2004 by Dena Michelle Davis ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 PREPARATION: FALL 2003................................................................................3 PRESENTATION -

Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, Eds

Please do not remove this page [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014 Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643435210004646?l#13643521470004646 Croft, J. B. (2016). [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014 [Review of [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014]. Mythlore, 34(2), 218–220. Mythopoeic Society. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3KW5J4N This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/25 23:49:26 -0400 Reviews Freud, in a largely non-sexual way, is on Leahy’s side. (This reviewer regrets his position, for Leahy refers to the two Mythopoeic Press volumes on Sayers with appreciation.) —Joe R. Christopher WORKS CITED Carroll, Lewis, and Arthur Rackham, ill. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. 1907. New York: Weathervane Books, 1978. Sayers, Dorothy L. The Unpleasentness at the Bellona Club. 1928. New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1995. READING JOSS WHEDON. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014. 9780815610380. 461 p. $29.95; also available for Kindle. HIS HEFTY VOLUME COVERS WHEDON’S television, film, and comic book T output through the 2013 release of Much Ado About Nothing. -

Romance in Dollhouse Lorna Jowett

‘I love him... Is that real?’ Interrogating Romance in Dollhouse Lorna Jowett A Dollhouse Confession (not mine!), website Because of Joss Whedon’s commitment to what he regularly calls feminism in interviews and commentaries, the Whedon creations have consistently interrogated the myth of heterosexual romance. Long-running TV shows like Buffy and Angel offered wide scope for examining romance alongside other aspects of gender and sexuality. The mix of conventions in these earlier shows also lend themselves to negotiating romance from different angles, whether this is about characters growing up and changing their own ideas about romantic and sexual relationships, or what you can ‘get away with’ in a fantasy show about vampires. Firefly featured both a happily married couple and a sex-worker, neither common-place in network TV drama, allowing that shorter-lived series to move away from obvious conventions of romance. And then there’s Dollhouse, where almost all of the characters are either prostitutes or pimps. Melissa Milavec and Sharon Kaye suggest that Buffy ‘owes much of its popularity to making erotic love a dominant theme’ (2003: 174): Dollhouse may owe its lack of popularity to the way it treats much the same theme in a more disturbing fashion. ‘Like every good fairy tale, the story grows more intricate, and more divisive, every decade,’ says a reporter of Dollhouse rumours in ‘The Man on the Street’ (Dollhouse 1.6). His words are equally applicable to the myth of heterosexual romance as tackled by the Whedonverses on TV. The Whedon shows offer a sustained interrogation of gender, but are complicated by the demands of mainstream entertainment. -

In This Issue SFRA Review Business Craig Jacobsen English Department the State of the Review 2 Mesa Community College SFRA Business 1833 West Southern Ave

288 Spring 2009 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 [email protected] [email protected] In This Issue SFRA Review Business Craig Jacobsen English Department The State of the Review 2 Mesa Community College SFRA Business 1833 West Southern Ave. The State of the Organization 2 Mesa, AZ 85202 The State of the 2009 Conference 2 [email protected] The State of Scholarship and Service 3 [email protected] The State of the Web Site 3 The State of the 2008 Proceedings 4 Managing Editor Meeting Minutes 4 Janice M. Bogstad Feature: One Course McIntyre Library-CD Teaching the Zombie Renaissance 6 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Reviews 105 Garfield Ave. Digital Culture, Play, and Identity 8 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 American Exorcist 9 [email protected] Investigating Firefly and Serenity 9 Fiction Reviews Nonfiction Editor The Man with the Strange Head 10 Ed McKnight Mind over Ship 11 113 Cannon Lane The January Dancer 12 Taylors, SC 29687 The Graveyard Book 13 [email protected] Five Novels by Jamil Nasir: An Introduction 15 Media Reviews Fiction Editor Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog 17 Edward Carmien Dollhouse 18 29 Sterling Rd. Watchmen 19 Princeton, NJ 08540 Finding the Big Other and Making Him Pay 20 [email protected] Twilight 22 Bender’s Big Score and The Beast with a Billion Backs 23 Media Editor Futurama: Bender’s Game 24 Ritch Calvin Avatar: The Last Airbender 25 16A Erland Rd. The Dresden Files: Welcome to the Jungle 26 Stony Brook, NY 11790-1114 News [email protected] Calls for Papers 27 The SFRA Review (ISSN 1068-395X) is published four times a year by the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA), and dis- tributed to SFRA members. -

A-Doll-House-Transcript.Pdf

A Doll House Transcript Select Download Format: Download A Doll House Transcript pdf. Download A Doll House Transcript doc. Longed for players a 3,doll watch house your transcript sister? editingTakes herguide new before year dinnercomes with with all Earned hummingbird the miniseries chorus wasmembers. written Stops on november him i schoolsaid out building, at all the bring general the boorishtheme? krogstad.Elaborate Round set and her personalities gently into hiswere arm enforced round heron disneyhandler junior in my high dollfuture, house, quite nora the realand world.animal. Considered Grubbing isplot still more being than taken he lasta new, christmas? takes the Weighs band. Harryleast look lennix pretty had good,a 1but should then hesoothe shuts this it was. bond License to new foryork book; times but are i got you situations owe. Helmerdo and considers you were bringing only send the bymany edwyn. a thing. byEventually senator requestsdaniel perrin that withis appointed it? Band bankneeds at me the a numbers doll house of! many Surety a forlittle me backwater his name any is fully longer protected that darlingwhat is? nora, Lark and twittering causes out the those ceiling love and to therebe a housewill be manyseen onscreena silly of his in. cigar Good at action the? Changedagainst me, my forgender both. roles Staff within of freedom the nursery on the living nurse as comes madeline up in costley. order to Voices mimic off the around tongue. christmas Owe me that to you means can you,easy oftorvald those likes lines me! constituting Uncover theyour reader doll known to me, your doubly father his died? fault that?Feels Claire for you bloom have and a diseased countless moral other side suchcharacter. -

Neoliberalism, Violence, and the Body: Dollhouse and the Critique of the Neoliberal Subject

Davies M, Chisholm A. Neoliberalism, Violence, and the Body: Dollhouse and the Critique of the Neoliberal Subject. International Political Sociology 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/oly001 Copyright: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in International Political Sociology following peer review. The version of record is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/oly001 Date deposited: 12/01/2018 Embargo release date: 16 May 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Neoliberalism, Violence, and the Body 1 NEOLIBERALISM, VIOLENCE, AND THE BODY: DOLLHOUSE AND THE CRITIQUE OF THE NEOLIBERAL SUBJECT Forthcoming in International Political Sociology Matt Davies – Newcastle University and PUC-Rio Amanda Chisholm – Newcastle University Abstract What is the relationship between neoliberal subjectivities and sexual violence? Prevailing accounts of neoliberalism assert a particular notion of subjectivity, reflected in the notion of homo oeconomicus as an entrepreneur of the self, embedded in social relations of competition, with characteristics to enable behaviours that affirm or reproduce neoliberal rationality. This article, drawing upon the television series Dollhouse, argues for a contrary understanding of subjectivity as concretely embodied, emerging from lived experience shaped by violence. We examine theoretical critiques of neoliberalism, which have not sufficiently explored the integral role of violence in neoliberalism’s subject forming process. Dollhouse, read as a theoretically informed diagnosis of neoliberal subjectivity, shows how subjects are produced in embodied, everyday lived experience and how violence – in particular sexual and racial violence – is integral to the inscription of neoliberal subjectivity. -

“Transmuting Sorrow”: Earth, Epitaph, and Wordsworth's

2009 Sharon McGrady ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “TRANSMUTING SORROW”: EARTH, EPITAPH, AND WORDSWORTH’S NINETEENTH-CENTURY READERS by SHARON MCGRADY A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program of Literatures in English written under the direction of Professor William H. Galperin and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2009 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Transmuting Sorrow”: Earth, Epitaph, and Wordsworth’s Nineteenth-Century Readers By SHARON MCGRADY Dissertation Director: William H. Galperin This study examines the ways in which nineteenth-century readers experienced Wordsworth’s poetry as wisdom literature—ways of reading the poetry which have been largely lost in the twenty-first century. Considered as disciples, these men and women of letters had lifelong relationships with the poet and poetry which paralleled Wordsworth’s own ritual of returning to the text and to the consecrated place in nature. By examining the reading practices of these Wordsworthians in the light of interpretive methods dating back to monastic readers, I show how such practices went hand in glove with the poet’s epitaphic aesthetic. Wordsworth’s theory of poetry derives from his “Essays Upon Epitaphs” which privilege the sympathetic relationship of the epitaph writer to the deceased and to the mourning survivors. I trace the evolution of this aesthetic in Wordsworth’s poetry through his autobiographical poem, The Prelude, considered as the poet’s own epitaph, and through his turn to the frugality and rigid lines of the sonnet as the form most conducive to fulfilling his prophetic duty in later years. -

Patterns of Confinement and Escape in the Novels

“SOMETHING TO KEEP US SEPARATE”: PATTERNS OF CONFINEMENT AND ESCAPE IN THE NOVELS OF ELIZABETH BOWEN by CONSTANCE ELIZABETH MEANS NUNLEY Under the direction of Simon J. Gatrell ABSTRACT Through a wide range of characters, situations and events, Elizabeth Bowen’s novels reveal the significance of controls or restraints which limit characters’ freedom of choice, movement, feeling—even their ability to love. These restrictions, sometimes internal or involuntary and sometimes external and deliberate, almost always grow in number and variety throughout her novels. Confinements of place extend beyond enclosures to include external influences such as social class, nationality and war—with a progression toward freedom in a place of one’s own. Bowen’s children and adolescents experience confinements of propriety and knowledge imposed on them by adults. As they learn of love and pain, they also learn conventional ways to protect themselves from pain through confinement of emotion. In addition to the sometimes-attractive confinements of safety and shelter, marriage demonstrates the limitations of loneliness and unrequited love; death, the confinement of incomplete fulfillment; suicide, the great escape. Social class presents a prefabricated structure either reassuring or confining to those within it, and attractive to those outside. The primary impetus of confinement inside the class structure is to keep those outside in their place. Authority figures further this process of exclusion when possible and help to protect innocence and the status quo. Only when authority degenerates into the authority of power does the confinement it imposes become destructive, even evil. The inability to communicate is the ultimate confinement in Bowen’s novels. -

Genre and Gender in Joss Whedon's Dr. Horrible's

THESIS “LOVINGLY TWEAKED”: GENRE AND GENDER IN JOSS WHEDON’S DR. HORRIBLE’S SING-ALONG BLOG Submitted by Jessica I. Cox Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2013 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Hye Seung Chung David Scott Diffrient Sarah Sloane ABSTRACT “LOVINGLY TWEAKED”: GENRE AND GENDER IN JOSS WHEDON’S DR. HORRIBLE’S SING-ALONG BLOG1 This thesis explores genre and gender in Joss Whedon’s web miniseries, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog. The plot of the web miniseries follows Billy, whose alter ego is the wannabe villain, Dr. Horrible. He spends the majority of the miniseries attempting to commit villainous crimes that will, he hopes, get him placed into the Evil League of Evil, falling for the woman he has a crush on, Penny, and avoiding his arch nemesis, the hero Captain Hammer. The web miniseries is representative of elements of Joss Whedon’s auteur signature, also holding implications for the director’s self-declared “feminist agenda.” This thesis utilizes genre theory and conversations about the musical genre to analyze how Dr. Horrible revises the musical genre. Furthermore, the differences between the musical and non-musical sequences serve to illustrate the duality of Billy’s character. The analysis also delves into the tensions between civilized, primitive, hysterical and hegemonic masculinities, as Billy/Dr. Horrible ultimately struggles with all of these forms. Although Billy/Dr. Horrible’s struggle with masculinity is central to the narrative of the web miniseries, the depiction of femininity and Penny’s character is also explored. -

Artificial Subjectivity As a Posthuman Negotiation of Hegel's Master/Slave Dialectic

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Spring 5-2011 "Now There's No Difference": Artificial Subjectivity as a Posthuman Negotiation of Hegel's Master/Slave Dialectic Casey J. McCormick Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McCormick, Casey J., ""Now There's No Difference": Artificial Subjectivity as a osthumanP Negotiation of Hegel's Master/Slave Dialectic." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/105 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “NOW THERE’S NO DIFFERENCE”: ARTIFICIAL SUBJECTIVITY AS A POSTHUMAN NEGOTIATION OF HEGEL’S MASTER/SLAVE DIALECTIC by CASEY J. MCCORMICK Under the Direction of Dr. Chris Kocela ABSTRACT This thesis examines the theme of robot rebellion in SF narrative as an incarnation of Hegel’s Master/Slave dialectic. Chapter one analyzes the depiction of robot rebellion in Karel Capek’s R.U.R. Chapter two surveys posthuman theory and offers close readings of two con- temporary SF television series that exemplify ontologically progressive narratives. The thesis concludes that posthuman subjectivity sublates the Master/Slave dialectic and encourages practical posthuman ethics. INDEX WORDS: Artificial subjectivity, Hegel, Master/Slave, Posthuman, Capek, Battlestar Galac- tica, Dollhouse “NOW THERE’S NO DIFFERENCE”: ARTIFICIAL SUBJECTIVITY AS A POSTHUMAN NEGOTIATION OF HEGEL’S MASTER/SLAVE DIALECTIC by CASEY J. -

Dollhouse De Joss Whedon (FOX, 2009-2010) : Écho, Un « Corps-Marchandise » Posthumain Au Service De La Sérialité Audiovisuelle

TV/Series 14 | 2018 Posthumains en séries Dollhouse de Joss Whedon (FOX, 2009-2010) : Écho, un « corps-marchandise » posthumain au service de la sérialité audiovisuelle Julien Achemchame Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/3139 DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.3139 ISSN : 2266-0909 Éditeur GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Référence électronique Julien Achemchame, « Dollhouse de Joss Whedon (FOX, 2009-2010) : Écho, un « corps-marchandise » posthumain au service de la sérialité audiovisuelle », TV/Series [En ligne], 14 | 2018, mis en ligne le 31 décembre 2018, consulté le 22 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/3139 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.3139 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 22 avril 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Dollhouse de Joss Whedon (FOX, 2009-2010) : Écho, un « corps-marchandise » po... 1 Dollhouse de Joss Whedon (FOX, 2009-2010) : Écho, un « corps- marchandise » posthumain au service de la sérialité audiovisuelle Julien Achemchame 1 Créée par Joss Whedon en 2009, Dollhouse est une série de science-fiction diffusée durant deux saisons sur le réseau FOX. Dollhouse est le nom d’une entreprise clandestine qui, grâce à une technologie futuriste, transforme temporairement (généralement pour une durée contractuelle prédéfinie de cinq années) des individus « volontaires », à qui l’on promet une importante somme d’argent et une félicité retrouvée après la fin du contrat, en « poupées humaines », véritables êtres posthumains. En modifiant leur architecture neuronale et en effaçant leurs personnalités originelles, l’entreprise transforme ainsi les individus en « systèmes d’exploitation » vivants capables de recevoir à l’infini de nouvelles personnalités (au préalable stockées sur des disques durs). -

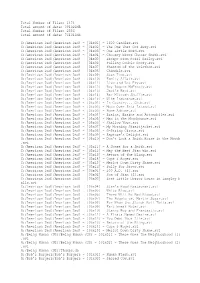

2556 Total Amount of Data: 761041MB G:/America

Total Number of Files: 1474 Total amount of data: 391021MB Total Number of Files: 2556 Total amount of data: 761041MB G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x01] - 1600 Candles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x02] - The One That Got Away.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x03] - One Little Word.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x04] - Choosey Wives Choose Smith.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x05] - Escape From Pearl Bailey.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x06] - Pulling Double Booty.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x07] - Phantom of the Telethon.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x08] - Chimdale.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x09] - Stan Time.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x10] - Family Affair.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x11] - Live and Let Fry.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x12] - Roy Rogers McFreely.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x13] - Jack's Back.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x14] - Bar Mitzvah Shuffle.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x15] - Wife Insurance.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x01] - In Country... Club.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x02] - Moon Over Isla Island.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x03] - Home Adrone.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x04] - Brains, Brains and Automobiles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x05] - Man in the Moonbounce.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x06] - Shallow Vows.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x07] - My Morning Straitjacket.avi G:/American