Corporate Governance in Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATVIA in REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30

LATVIA IN REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30 CONTENTS Government Latvia's Civic Union and New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party About 1,700 people Have Expressed Wish to Join Latvia's Newly-Founded ZRP Party President Bērziņš to Draft Legislation Defining Criteria for Selection of Ministers Parties Represented in Current Parliament Promise Clarity about Candidates This Week Procedure Established for President’s Convening of Saeima Meetings Economics Bank of Latvia Economist: Retail Posts a Rapid Rise in June Latvian Unemployment Down to 12.3% Fourteen Latvian Banks Report Growth of Deposits in First Half of 2011 European Commission Approves Cohesion Fund Development Project for Rīga Airport Private Investments Could Help in Developing Rīga and Jūrmala as Tourist Destinations Foreign Affairs Latvian State Secretary Participates in Informal Meeting of Ministers for European Affairs Cabinet Approves Latvia’s Initial Negotiating Position Over EU 2014-2020 Multiannual Budget President Bērziņš Presents Letters of Accreditation to New Latvian Ambassador to Spain Society Ministry of Culture Announces Idea Competition for New Creative Quarter in Rīga Unique Exhibit of Sand Sculptures Continues on AB Dambis in Rīga Rīga’s 810 Anniversary to Be Celebrated in August with Events Throughout the Latvian Capital Labadaba 2011 Festival, in the Līgatne District, Showcases the Best of Latvian Music Latvian National Opera Features Special Summer Calendar of Performances in August Articles of Interest Economist: “Same Old Saeima?” Financial Times: “Crucial Times for Investors in Latvia” L’Express: “La Lettonie lutte difficilement contre la corruption” Economist: “Two Just Men: Two Sober Men Try to Calm Latvia’s Febrile Politics” Dezeen magazine: “House in Mārupe by Open AD” Government Latvia's Civic Union, New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party At a party congress on July 30, Latvia's Civic Union party voted to participate in the foundation of the Unity party, Civic Union reported in a statement on its website. -

Fourth Report to the Council and the European Parliament on Monitoring Development in the Rail Market

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 13.6.2014 COM(2014) 353 final PART 1/2 REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Fourth report on monitoring development of the rail market {SWD(2014) 186 final} EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Fourth report on monitoring development of the rail market TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Evolution of internal market in rail services................................................................ 4 1.1. The objectives of the White Paper on Transport (2011).............................................. 4 1.2. The passenger rail market today .................................................................................. 5 1.3. Evolution of the passenger rail market......................................................................... 8 1.4. The rail freight market today........................................................................................ 9 1.5. Evolution of the rail freight market.............................................................................. 9 2. Evolution of the internal market in services to be supplied to railway undertakings 11 2.1. Stations....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1. Stations across the European Union........................................................................... 11 2.1.2. Ownership and management...................................................................................... 12 2.1.3. Access -

Read More on Baltic International

INNOVATIONS TEAM aimed at innovations EXCELLENT OF EXPERTS and excellence SERVICE 25 REASONS WE ARE PROUD OF know-how truly individual high and experience quality service FAMILY BANK a bank owned SUPPORT by family TRUST TO STARTUPS and devoted we appreciate we believe in future to families trust of clients of start-ups and employees ESG JOY OF 25YEAR Environmental. WORKING EXPERIENCE GOOD Social. TOGETHER Let’s celebrate RESOURCE BASE Government. we love to work 25th anniversary strong resource base together! on May 3 and OUR WAY and sound development entire year 2018! OF SUCCESS, CHALLENGES RELIABILITY SUSTAINABILITY we are reliable, AND gold level open and honest in Sustainability index long-term business VICTORIES partner PATRONS SUPPORT OF CULTURE TO LITERATURE WINNERS SUCCESSION AND ART we believe in power #WinnersBorninLatvia we believe in importance care for succession of literature of families and succession of national values SMART EXPERTISE INVESTMENTS helps to find OFFICE we invest with our clients the best solutions IN THE HEART in a smart way OF OLD RIGA for our customers working in the rhythm of the heartbeats of Riga RESPECTFUL SHAREHOLDERS we trust our shareholders, RESPONSIBILITY STRONG TEAM GREEN SPORTIVE AND COMPETITIVE and they trust us responsible for wealth good team of energetic THINKING ENTHUSIASTIC PRODUCTS management of our clients and loyal experts care for nature we enjoy working wide spectrum and ourselves and sporting together and competitive features Business review 2017 CONTENTS 3 Valeri Belokon, Chairman of Supervisory Board 5 Viktor Bolbat, Deputy Chairman of Management Board 7 Bank financial results review 10 Overall review of Latvian economy 13 Developments on global financial markets 15 Baltic International Bank: support to the society, environment, and the world 19 Baltic International Bank — 25! VALERI BELOKON e Chairperson of the Supervisory Board of Baltic International Bank Whatever you do in life, do it with all your heart. -

Study on Border Crossing Practices in International Railway Transport

STUDY ON BORDER CROSSING PRACTICES IN INTERNATIONAL RAILWAY TRANSPORT Bangkok, 2018 This study was prepared by Transport Division ESCAP. The draft of the study was prepared by Mr. Goran Andreev, Consultant, under the supervision of Mr. Sandeep Raj Jain, Economic Affairs Officer, Transport Facilitation and Logistics Section (TFLS), Transport Division. Overall guidance was provided by Mr. Li Yuwei, Director, Transport Division. The study extensively benefited from the visits made by the ESCAP study team to several border crossings (in chronological order): Sukhbaatar (Mongolia), Dong Dang (Viet Nam), Padang Besar (Malaysia), Sarkhas (Islamic Republic of Iran), Rezekne (Latvia). The assistance provided by the railways, customs and other authorities at these border crossings, their officers and staff for the study is duly appreciated. Acknowledgments are also extended to the representatives of Intergovernmental Organisation for International Carriage by Rail (OTIF) and Organisation for Co- operation between Railways (OSJD), for their constructive comments on the draft Study and the contribution in providing valuable inputs on the publication. The views expressed in this guide are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. The opinions, figures and estimates set forth in this guide are the responsibility of the authors, and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or carrying the endorsement of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this study do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

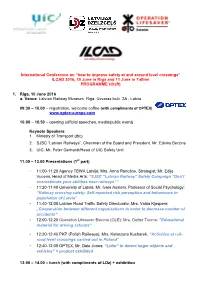

ILCAD 2016, 10 June in Riga and 11 June in Tallinn PROGRAMME (Draft)

International Conference on “how to improve safety at and around level crossings” ILCAD 2016, 10 June in Riga and 11 June in Tallinn PROGRAMME (draft) 1. Riga, 10 June 2016 a. Venue: Latvian Railway Museum, Riga, Uzvaras bulv. 2A ; Latvia 09:30 – 10.00 – registration, welcome coffee (with compliments of OPTEX) www.optex-europe.com 10:00 – 10.50 – opening (official speeches, media/public event) Keynote Speakers : 1. Ministry of Transport (tbc) 2. SJSC “Latvian Railways”, Chairman of the Board and President, Mr. Edvins Berzins 3. UIC: Mr. Peter Gerhardt/Head of UIC Safety Unit 11.00 – 13.00 Presentations (1 st part) • 11:00-11:20 Agency TBWA Latvija: Mrs. Anna Ranc āne, Strategist; Mr. Edijs Vucens, Head of Media Arts: “SJSC “Latvian Railway” Safety Campaign “Don’t overestimate your abilities near railways”” • 11:20-11:40 University of Latvia: Mr. Ivars Austers, Professor of Social Psychology: “Railway crossing safety: Self-reported risk perception and behaviours in population of Latvia” • 11:40-12:00 Latvian Road Traffic Safety Directorate: Mrs. Valda Kjaspere: „Cooperation between different organizations in order to decrease number of accidents“ • 12:00-12:20 Operation Lifesaver Estonia (OLE): Mrs. Getter Toome: "Educational material for driving schools” • 12:20-12:40 PKP (Polish Railways): Mrs. Katarzyna Kucharek, “Activities at rail- road level crossings carried out in Poland” • 12:40-13:00 OPTEX, Mr. Dale Jones: “Lidar” to detect larger objects and vehicles” + product exhibited 13:00 – 14.00 – lunch (with compliments of LDz) + exhibition 14.00 – 16.00 – Presentations (2 nd part) • 14:00 – 14:30 Inspector Becky Warren , British Transport Police, UK Network Rail, UK: Mr. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013) 540 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area 1. INTRODUCTION Since the adoption of the euro by Estonia on 1 January 2011, the euro area consists of seventeen EU Member States. Among the remaining eleven Member States, nine Member States are expected to adopt the euro once the necessary conditions are fulfilled. Denmark and the United Kingdom have a special "opt-out"-status and are not committed to adopt the euro. This report assesses the state of play of the practical preparations for introducing the euro in Latvia and evaluates the progress made in preparing the changeover related communication campaign. Following the Council decision from 9 July 2013 concluding that the necessary conditions for euro adoption are fulfilled, Latvia will adopt the euro on 1 January 2014 ("€- day"). The conversion rate between the Latvian lats and the euro has been irrevocably fixed at 0.702804 Latvian lats to one euro. 2. STATE OF PLAY OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE CHANGEOVER IN LATVIA Latvia will be the sixth of the group of Member States which joined the EU in 2004 to adopt the euro. Latvia's original target date of 1 January 2008 foreseen in the Action Plan for Implementation of the Single European Currency of 1 November 2005 was subsequently reconsidered. -

Xcre-Establishment of the Lats

XC BANK OF LATVIA IN TIMES OF CHANGE (1990–2004) Dr. hist. Kristīne Ducmane XCRE-ESTABLISHMENT OF THE LATS 209 In a wider, not merely economic but also cultural, historic and future currency of Latvia. This unconventional approach to the political sense, money reflects the entire process of the evolution solution of the currency design caught the assessors' attention. of the civilisation. It is often evidence of political changes in a Soon the public authorities also joined the efforts to re-estab- country and is definitely part of the world's cultural heritage. The lish the lats, the national currency. On 31 July 1990 the Supreme link between the restoration of sovereign Latvia and the re-estab- Council of the Republic of Latvia (hereinafter, the Supreme lishment of the lats is particularly interesting in the history of Lat- Council) adopted a Resolution "On the programme for estab- vian money. The restoration of Latvia's independence was an op- lishing the monetary system of the Republic of Latvia"2 whereby portunity to restore the national currency. The re-establishment of the Council of the Bank of Latvia was assigned the task of estab- the lats and stabilisation of the national economy was the goal of lishing a commission that would be in charge of the monetary the second currency reform in sovereign Latvia. Work towards system reform. The commission's working programme had to achieving this goal began at the dawn of the national awakening. address issues related to the laws regulating money and lending At the meeting at the Artists' Union in June 1988 Mr. -

Privatization at the Crossroad of Latvia's Economic Reform

PRIVATIZATION AT THE CROSSROAD OF LATVIA'S ECONOMIC REFORM Sandra Berzups" I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 171 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................. 172 III. ECONOMIC REFORM ........................................................ 175 IV. PRIVATIZATION - THE BEGINNING ....................................... 177 V. RESTITUTION ................................................................. 179 VI. PRIVATIZATION CERTIFICATES ........................................... 180 VII. SECTORAL PRIVATIZATION - AGRICULTURE ........................... 182 VIII. SECTORAL PRIVATIZATION - BANKING .................................. 183 IX. SMALL SCALE PRIVATIZATION ........................................... 185 X. LARGE PRIVATIZATION ..................................................... 186 XI. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRIVATIZATION AGENCY ................... 188 XII. NEW PRIVATIZATION METHODOLOGY FOR THE PRIVATIZATION AGENCY - THE SPECIFICS ............................. 190 XIII. NEW PRIVATIZATION METHODOLOGY FOR PRIVATIZATION COMMITTEES - THE SPECIFICS ........................ 192 XIV. ANALYSIS OF NEW METHODOLOGY ..................................... 193 XV. CONCLUSION ................................................................. 195 I. INTRODUCTION Latvia regained its independence from the former Soviet Union in August 1991. Since then, it has begun the slow and arduous path of replacing the centrally-planned, socialist system with an economic structure based -

Economic and Social Council Distr

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Council Distr. GENERAL TRANS/WP.5/2002/1/Add.2 14 June 2002 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Transport Trends and Economics (Fifteenth session, 2- 4 September 2002, agenda item 5) DEVELOPMENT REGARDING TRANSPORT POLICIES Replies to the questionnaire on transport development Addendum 2 Transmitted by the Government of Latvia Note: At its fifty-ninth session the Inland Transport Committee, following an earlier decision taken at its fortieth session (ECE/TRANS/42, para. 45), agreed to circulate the questionnaire on the most significant criteria for the determination of new and important developments with regard to inland transport in the member countries of general interest to Governments (ECE/TRANS/119, para. 52). * * * TRANS/WP.5/2002/1/Add.2 page 2 I. General transport policy aspects 1. 1.1. The Government of the Republic of Latvia has two programmes on transport policy in general: - National Transport Development Programme (2000-2006 year) - Railway Transport Development State Programme (1995-2010 year) The “Declaration on the intended activities of the Cabinet of Ministers” envisages the following activities regarding the development of the transport system: - Creation of a stable and long-term road network financing system according to the principle adopted in the road sector that the road user pays for road use. The distribution of revenues from the excise duty on oil products has been achieved up until April 2002: 60% in the special State budget – the State Road Fund (SRF) and 40% in the State consolidated budget instead of the previous distribution of 50% / 50%. -

How Great Is Latvia's Success Story? the Economic, Social and Political Consequences of the Recent Financial Crisis in Latvia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Austers, Aldis Article — Published Version How great is Latvia's success story? The economic, social and political consequences of the recent financial crisis in Latvia Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Austers, Aldis (2014) : How great is Latvia's success story? The economic, social and political consequences of the recent financial crisis in Latvia, Intereconomics, ISSN 1613-964X, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 49, Iss. 4, pp. 228-238, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10272-014-0504-0 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/146024 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Financial Crisis DOI: 10.1007/s10272-014-0504-0 Aldis Austers* How Great Is Latvia’s Success Story? The Economic, Social and Political Consequences of the Recent Financial Crisis in Latvia The current state of Latvia can be best described in medical terms: the patient is pale, but alive. -

Commission Staff Working Document Impact

Council of the European Union Brussels, 22 November 2017 (OR. en) 12442/17 Interinstitutional File: ADD 3 REV 1 2017/0237 (COD) TRANS 370 CODEC 1477 CONSOM 307 COVER NOTE From: Secretary-General of the European Commission, signed by Mr Jordi AYET PUIGARNAU, Director date of receipt: 21 November 2017 To: Mr Jeppe TRANHOLM-MIKKELSEN, Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union No. Cion doc.: SWD(2017) 318 final/2 Subject: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation from the European Parliament and the Council on rail passengers' rights and obligations (recast) Delegations will find attached document SWD(2017) 318 final/2. Encl.: SWD(2017) 318 final/2 12442/17 ADD 3 REV 1 TA/el DGE 2A EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 21.11.2017 SWD(2017) 318 final/2 CORRIGENDUM This document corrects document SWD(2017) 318 final of 27.9.2017 Missing annexes are added The text shall read as follows: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation from the European Parliament and the Council on rail passengers' rights and obligations (recast) EN EN Table of Contents 1 WHAT IS THE PROBLEM AND WHY IS IT A PROBLEM? ........................... 5 1.1 Policy Context and Key Problems at Stake ................................................... 5 1.2 Description of the main problems linked to the current application of the rail passenger rights legislation (Part I) ........................................... 11 1.2.1 Major issues with the regulation .................................................................. 11 1.2.1.1 Problems linked to the scope of the rail passenger rights legislation (Exemptions) ............................................................................... -

CASE AT.39813 Baltic Rail ANTITRUST PROCEDURE Council

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition CASE AT.39813 Baltic rail (Only the English text is authentic) ANTITRUST PROCEDURE Council Regulation (EC) 1/2003 Article 7 Regulation (EC) 1/2003 Date: 02/10/2017 This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision is published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Parts of this text have been edited to ensure that confidential information is not disclosed. Those parts are replaced by a non-confidential summary in square brackets or are shown as […]. EN EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 2.10.2017 C(2017) 6544 final COMMISSION DECISION of 2.10.2017 relating to proceedings under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union AT.39813 - Baltic Rail (Only the English text is authentic) EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 8 2. Parties to the proceedings ............................................................................................. 8 2.1. The addressee of the decision ...................................................................................... 8 2.2. The complainant ........................................................................................................... 8 3. Procedure ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. Description of LG's practices which are the subject of this decision ........................