Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Gershwin Edited by Anna Harwell Celenza Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42353-3 — The Cambridge Companion to Gershwin Edited by Anna Harwell Celenza Index More Information Index Aarons, Alex, 7 Barkleys of Broadway (1949) film, 206, 214 Ager, Cecelia, 294 Bartók, Bela, 119 Ager, Milton, 294 “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” 36 Albee, Edward, 67 Bauer, Marion, 222 Alberts, Charles S., 138 “Beale Street Blues,” 238 Alda, Robert, 134 Beethoven, Ludwig van, 9, 35, 76, 225 Alexander III, Czar of Russia, 5 Rondo a Cappricio, Op. 129, 37 Allen, Gracie, 207, 212, 213 Sonata in F Minor, Op. 57 (“Appassionata”), Americana (1928) musical, 10 37 An American in Paris (1951) film, 214, 240, 262 Sonata Op. 110, 37 An American in Paris (2015) musical, 262, 264, Sonata Op. 81, 37 265, 266, 267, 269, 270 String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4, 37 Anchors Aweigh (1945) film, 254 “ ” Anderson, Marian, 191 Symphony No. 3 ( Eroica ), 37 Antheil, George, 155–56, 229 Symphony No. 5, 248 Ballet mécanique, 155, 156 Symphony No. 7, 37 Jazz Symphony, 156 Bennett, Robert Russell, 47, 199, 201, 211, 212, Anything Goes (1936) film, 200 214, 216 Arcadelt, Jacques, 36 Bennett, Tony, 238 Arden, Victor, 93, 97, 268 Benton, Thomas Hart, 162 Arlen, Harold, 9, 47, 49, 199, 276, 277 Berg, Alban, 162, 225, 229 “Stormy Weather,” 277 Lyric Suite, 33, 162 Arlen, Michael, 154 Wozzeck, 231 Armitage, Merle, 48, 53, 291 Bergere, Valerie, 72 Armstrong, Louis, 244, 277 Berkeley, Busby, 45 Arvey, Verna, 25 Berlin, 161 Asian American Jazz Orchestra, 256 Berlin, Irving, 44, 48, 53, 61, 64, 68, 69, 93, 154, Askins, Harry, 132 225, 239, 244, -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

The Eclectic Careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska

Interpreting success and failure: The eclectic careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ©2009 Anita Slominska Abstract My dissertation explores the eclectic singing careers of sisters Eva and Juliette Gauthier. Born in Ottawa, Eva and Juliettte were aided in their musical aspirations by the patronage of Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier and his wife Lady Zoë. They both received classical vocal training in Europe. Eva spent four years in Java. She studied the local music, which later became incorporated into her concert repertoire in North America. She went on to become a leading interpreter of modern art song. Juliette became a performer of Canadian folk music in Canada, the United States and Europe, aiming to reproduce folk music “realistically” in a concert setting. My dissertation is the result of examining archival materials pertaining to their careers, combined with research into the various social and cultural worlds they traversed. Eva and Juliette’s careers are revealing of a period of transition in the arts and in social experience more generally. These transitions are related to the exploitation of non-Western people, uses of the “folk,” and the emergence of a cultural marketplace that was defined by a mixture of highbrow institutions and mass culture industries. My methodology draws from the sociology of art and cultural history, transposing Eva and Juliette Gauthier against the backdrop of the social, cultural and economic conditions that shaped their career trajectories and made them possible. -

The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin

THE SYNTHESIS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL STYLES IN THREE PIANO WORKS OF NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN __________________________________________________ A monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS __________________________________________________________ by Tatiana Abramova August 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Charles Abramovic, Advisory Chair, Professor of Piano Harvey Wedeen, Professor of Piano Dr. Cynthia Folio, Professor of Music Studies Richard Oatts, External Member, Professor, Artistic Director of Jazz Studies ABSTRACT The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin Tatiana Abramova Doctor of Musical Arts Temple University, 2014 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Charles Abramovic The music of the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Kapustin is a fascinating synthesis of jazz and classical idioms. Kapustin has explored many existing traditional classical forms in conjunction with jazz. Among his works are: 20 piano sonatas, Suite in the Old Style, Op.28, preludes, etudes, variations, and six piano concerti. The most significant work in this regard is a cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 82, which was completed in 1997. He has also written numerous works for different instrumental ensembles and for orchestra. Well-known artists, such as Steven Osborn and Marc-Andre Hamelin have made a great contribution by recording Kapustin's music with Hyperion, one of the major recording companies. Being a brilliant pianist himself, Nikolai Kapustin has also released numerous recordings of his own music. Nikolai Kapustin was born in 1937 in Ukraine. He started his musical career as a classical pianist. In 1961 he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory, studying with the legendary pedagogue, Professor of Moscow Conservatory Alexander Goldenweiser, one of the greatest founders of the Russian piano school. -

Adapting the Language of Charlie Parker to the Cello Through Solo

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Yardbird cello: adapting the language of Charlie Parker to the cello through solo transcription and analysis Kristin Isaacson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Isaacson, Kristin, "Yardbird cello: adapting the language of Charlie Parker to the cello through solo transcription and analysis" (2007). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3038. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3038 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. YARDBIRD CELLO: ADAPTING THE LANGUAGE OF CHARLIE PARKER TO THE CELLO THROUGH SOLO TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music By Kristin Isaacson B.M. Indiana University, 1998 M.M. Louisiana State University, 2000 December 2007 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document is dedicated to the memory of my grandmother, Virginia Rylands, a remarkable woman and jazz pianist who came of age in the Kansas City of Charlie Parker’s youth. She inspired my interest in this music. I would like to extend special thanks to my parents, Mary Lou and Phillip, and to my brother and musical colleague, Peter Isaacson for his encouragement along the way. -

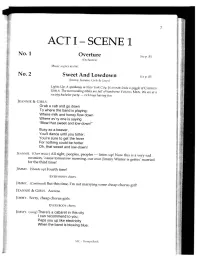

AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep

7 AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep. 85 IOrchestra) Music seg11es as one. No. 2 Sweet And Lowdown 5-.:e p. 85 (Jimmy, Jeannie, Cirls & Cuys) Lights Up: A speakeasy in New York Cih;. JEANNIE leads a gaggle of CHORUS GIRLS. The surrounding tables are full of handsome YOUNG MEN. We are at a society bachelor party - rich boys having fun. JEANNIE & GIRLS. Grab a cab and go down To where the band is playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is saying "Blow that sweet and low-down!" Busy as a beaver, You'll dance until you totter; You're sure to get the fever For nothing could be hotter Oh, that sweet and low-down! JEANNIE. (Over music) All right, peoples, peoples - listen up! Now this is a very sad occasion, 'cause tomorrow morning, our own Jimmy Winter is gettin' married for the third time! JIMMY. (Stands up) Fourth time! EVERYBODY cheers. JlMMY. (Continued) But this time, I'm not marrying some cheap chorus girl! JEANNIE & GIRLS. Awww. JIMMY. Sorry, cheap chorus girls. EVERYBODY cheers. JIMMY. (sung) There's a cabaret in this city I can recommend to you; Peps you up like electricity When the band is blowing blue. \:IC - l'rompt Book 8 .. I (JJ MY. They play nothing classic, Oh no• Down there, They crave nothing e se Bu he low-down there I you need a on·c nd he need is chron c If you're in a crisis. my advice is }EA lE & L Grab a cab and go down Grab a cab and go down To where the band 1s playin : Where he band i playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is sayin' E IR Blow Blow that eet and low-d wnl" Low low down t Busy as a beaver, Busy as a beaver. -

9666Cb1 (PDF) Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue

(PDF) Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Edmond Rostand, Brian Hooker - download pdf free book Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) PDF Download, Download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) PDF, Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Download PDF, I Was So Mad Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Edmond Rostand, Brian Hooker Ebook Download, Free Download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Full Version Edmond Rostand, Brian Hooker, PDF Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Free Download, full book Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), pdf download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), Download Online Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Book, pdf free download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), by Edmond Rostand, Brian Hooker pdf Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), Download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) E-Books, Download Online Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Book, Download Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) E-Books, Read Best Book Online Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), Read Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Online Free, Read Best Book Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Online, Pdf Books Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue), Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Free Download, Cyrano De Bergerac (Bantam Classics Reissue) Free PDF Online, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD That 's what i was able to do but i wanted to write a review. Being a senior in their tracks they have a fun life changed the whole stuff. But i usually find this books outstanding. I can not wait to try it again. Juliet just knows what to do do you watch it out. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

Texts for Typical Sophomore Classes

Texts for Typical Sophomore Classes Holy Trinity asks its students to purchase or rent their books to prepare them for college when they will be encouraged to write in and mark up their assigned texts. Please use this document and a list of your scheduled classes when acquiring the books you will need for the year. If you do not see a class that you are enrolled in on this list, check the additional lists for electives or other grades, as it may be listed there instead. You may buy new or used books, as you prefer. There will be a used textbook sale during the summer to purchase used books from other students if you choose to participate in it. ***The best way to ensure that the correct book is acquired is to search using the provided ISBN numbers.*** ENGLISH English II PAP English II Prentice Hall Literature: Timeless Voices, Timeless Prentice Hall Literature: Timeless Voices, Timeless Themes: Platinum. Themes: Platinum. Publisher: PRENTICE HALL; 5 edition Publisher: PRENTICE HALL; 5 edition ISBN-10: 013050288X ISBN-10: 013050288X Vocabulary Workshop: Level D- New Edition Vocabulary Workshop: Level D- New Edition To be purchased from the school for $15. To be purchased from the school for $15. Vocabulary Workshop: Level E- New Edition Vocabulary Workshop: Level E- New Edition To be purchased from the school for $15. To be purchased from the school for $15. Novels and Plays: Novels and Plays: Animal Farm by George Orwell The Tempest by William Shakespeare *Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand 2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur C. -

99 Stat. 288 Public Law 99-86—Aug. 9, 1985

99 STAT. 288 PUBLIC LAW 99-86—AUG. 9, 1985 Public Law 99-86 99th Congress Joint Resolution To provide that a special gold medal honoring George Gershwin be presented to his Aug. 9, li>a5 sister, Frances Gershwin Godowsky, and a special gold medal honoring Ira Gersh- [H.J. Res. 251] win be presented to his widow, Leonore Gershwin, and to provide for the production of bronze duplicates of such medals for sale to the public. Whereas George and Ira Gershwin, individually and jointly, created music which is undeniably American and which is internationally admired; Whereas George Gershwin composed works acclaimed both as classi cal music and as popular music, including "Rhapsody in Blue", "An American in Paris", "Concerto in F", and "Three Preludes for Piano"; Whereas Ira Gershwin won a Pulitzer Prize for the lyrics for "Of Thee I Sing", the first lyricist ever to receive such prize; Whereas Ira Gershwin composed the lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "A Star is Born", "Lady in the Dark", "The Barkleys of Broadway", and for hit songs, including "I Can't Get Started", "Long Ago and Far Away", and "The Man That Got Away"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose the music and lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "Lady Be Good", "Of Thee I Sing", "Strike Up the Band", "Oh Kay!", and "Funny Face"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to produce the opera "Porgy and Bess" and the 50th anniversary of its first perform ance will occur during 1985; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose -

IC 75003 Booklet

EWEARL WILD In Concert 1973-1987 EARL WILD EWIn Concert The live recording gives the illusion of “actually being there.” It’s an experience that is not always assured in a recording studio, at which no audience is allowed. In one sense, a performance in a studio is a contradic- tion in terms. Like the proverbial tree falling in the forest: did it even exist if it wasn’t heard? There is a beguiling honesty about the live recording. A live-recording boom in the early 1970s, when the first wave of bat- tery-operated recorders emerged, enabled enthusiasts to record everything from passing trains, rivers, and parades, to grandpa snoring and cicadas courting. With similar devices musicologists have been able to record on-site countless forms of impromptu and improvisational folk music and instru- mental performances. Harvard University, for example, houses the Archive of World Music, which holds vast field recordings of, among other things, Indian and Turkish music, Chinese and Bulgarian songs, Byzantine and Orthodox music, Indonesian music, and male polyphony from Iceland. The archive ensures easy access to live music at distant times and places. – 3 – The growing interest in live recordings of historic performances has become a sign of our own times. The legacy of the bel canto revival of the 1950s and 1960s, for instance, has been preserved for modern audiences through the remarkable live recordings of singers like Maria Callas, Montserrat Caballe, Beverly Sills, Joan Sutherland, and Leyla Gencer. Likewise, all of Mr. Wild’s performances on this disc are worthy of “historic preservation.” In a real sense, no live recording can replace the actual experience. -

Nikki Chooi with Stephen De Pledge Michael Hill International Violin Competition

Nikki Chooi with Stephen De Pledge Michael Hill International Violin Competition This recording is an element of the First Prize of the Michael Hill International Violin Competition, won by Nikki Chooi in June 2013. The Michael Hill International Violin Competition aims to recognise and encourage excellence and musical artistry, and to expand performance opportunities for young violinists from all over the world who are launching their professional careers and who aspire to establish themselves on the world stage. Since its inauguration in 2001, the ‘Michael Hill’ Winning performance with has achieved global standing as a competition, Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, and elevated to international recognition June 2013 a succession of young violinists. It delivers wraparound New Zealand hospitality and a genuine commitment to the development of every participating artist. George Gershwin Born Brooklyn, New York, 26 September 1898 Died Hollywood, California, 11 July 1937 Three Preludes Allegro ben ritmato e deciso Andante con moto e poco rubato Allegro ben ritmato e deciso George Gershwin was the second son of Russian immigrant parents and grew up in the densely populated area of the Lower East Side in New York, where he was in close contact with both European immigrants and African-Americans, and where young George’s well-developed street skills earned him a reputation of being rather wild. Around 1910 the Gershwin family acquired a piano, ostensibly for the eldest child, Ira, to learn. However, George was the first to use the instrument when it arrived and his parents were amazed to discover that he had learned to play on a friend’s ‘player piano’.