View of Liturature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

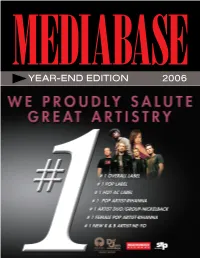

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

2017 Songbooks (Autosaved).Xlsx

Song Title Artist Code 1 Mortin Solveig & Same White 21412 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 20606 1999 Prince 20517 #9 dream John Lennon 8417 1 + 1 Beyonce 9298 1 2 3 One Two Three Len Barry 4616 1 2 step Missy Elliot 7538 1 Thing Amerie 20018 1, 2 Step Ciara ft. Missy Elliott 20125 10 Million People Example 10203 100 Years Five For Fighting 4453 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6117 1000 miles away Hoodoo Gurus 7921 1000 stars natalie bathing 8588 12:51 Strokes 4329 15 FEET OF SNOW Johnny Diesel 9015 17 Forever metro station 8699 18 and life skid row 7664 18 Till i die Bryan Adams 8065 1959 Lee Kernagan 9145 1973 James Blunt 8159 1983 Neon Trees 9216 2 Become 1 Jewel 4454 2 FACED LOUISE 8973 2 hearts Kylie Minogue 8206 20 good reasons thirsty merc 9696 21 Guns Greenday 8643 21 questions 50 Cent 9407 21st century breakdown Greenday 8718 21st century girl willow smith 9204 22 Taylor Swift 9933 22 (twenty-two) Lily Allen 8700 22 steps damien leith 8161 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 21533 3 (one two three) Britney Spears 8668 3 am Matchbox 20 3861 3 words cheryl cole f. will 8747 4 ever Veronicas 7494 4 Minutes Madonna & JT 8284 4,003,221 Tears From Now Judy Stone 20347 45 Shinedown 4330 48 Special Suzi Quattro 9756 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 21195 5, 6, 7, 8. steps 8789 50 50 Lemar 20381 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 1805 50 ways to say Goodbye Train 9873 500 miles Proclaimers 7209 6 WORDS WRETCH 32 21068 7 11 BEYONCE 21041 7 Days Craig David 2704 7 things Miley Cyrus 8467 8675309 Jenny Tommy Tutone 1807 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 20210 99 Red Balloons Nena -

Whitney Houston

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 1 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Whitney Houston No. of Titles Positions Whitney Elizabeth Houston (August 9, 1963 – February Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 11, 2012) was an American singer and actress. She was 1 31 8 3 445 74 13 cited as the most awarded female artist of all time by 1 37 18 4 438 88 16 Guinness World Records and remains one of the best- 1 40 23 11 689 183 31 selling music artists of all time with 200 million records sold worldwide. 1 46 29 12 1.572 345 60 ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Hold Me 01/1986 44 7 06/1984 46 18 as ► Teddy Pendergrass with Whitney Houston 2 You Give Good Love 08/1985 93 1 05/1985 3 21 6 3 Saving All My Love For You 01/1986 18 15 11/1985 1 2119 8708/1985 1 22 4 How Will I Know 03/1986 26 9 01/1986 5 13 4612/1985 1 2 24 5 Greatest Love Of All 05/1986 30 10 04/1986 8 13 3703/1986 1 3 20 6 I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 05/1987 1 5 21 1205/1987 1 2218 805/1987 1 20 9 7 Didn't We Almost Have It All 08/1987 20 9 08/1987 14 9 08/1987 1 2 17 7 8 So Emotional 11/1987 5 11 3810/1987 1 1 19 9 Where Do Broken Hearts Go 03/1988 14 9 02/1988 1 2 18 6 10 Love Will Save The Day 07/1988 37 13 05/1988 10 7 1107/1988 9 16 11 One Moment In Time 09/1988 1 2 23 9609/1988 1 2 16 09/1988 5 17 4 12 I Know Him So Well 01/1989 46 5 as ► Cissy & Whitney Houston 13 It Isn't, It Wasn't, It Ain't Never Gonna Be 09/1989 29 5 07/1989 41 8 as ► -

Whitney Houston | Primary Wave Music

WHITNEY HOUSTON facebook.com/WhitneyHouston instagram.com/whitneyhouston/ Image not found or type unknown youtube.com/channel/UC7fzrpTArAqDHuB3Hbmd_CQ whitneyhouston.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitney_Houston open.spotify.com/artist/6XpaIBNiVzIetEPCWDvAFP With over 200 million combined album, singles and videos sold worldwide during her career with Arista Records, Whitney Houston has established a benchmark for superstardom that will quite simply never be eclipsed in the modern era. She is a singer’s singer who has influenced countless other vocalists female and male. Music historians cite Whitney’s record-setting achievements: the only artist to chart seven consecutive #1 Billboard Hot 100 hits (“Saving All My Love For You,” “How Will I Know,” “Greatest Love Of All,” “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me),” “Didn’t We Almost Have It All,” “So Emotional,” and “Where Do Broken Hearts Go”); the first female artist to enter the Billboard 200 album chart at #1 (her second album, Whitney, 1987); and the only artist with eight consecutive multi-platinum albums (Whitney Houston, Whitney, I’m Your Baby Tonight, The Bodyguard, Waiting To Exhale , and The Preacher’s Wife soundtracks; My Love Is Your Love and Whitney: The Greatest Hits). In fact, The Bodyguard soundtrack is one of the top 5 biggest-selling albums of all-time (at 18x-platinum in the U.S. alone), and Whitney’s career-defining version of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” is the biggest-selling single of all time by a female artist (at 8x-platinum for physical and digital in the U.S. alone). Born into a musical family on August 9, 1963, in Newark, New Jersey, Whitney’s success might’ve been foretold. -

236 Valentine's Day Songs (2015)

236 Valentine's Day Songs (2015) Song Name Time Artist Album Theme Lay All Your Love On Me 3:02 ABBA The Definitive Collection passion Take a Chance on Me 4:05 Abba Gold romance Love in an Elevator 5:21 Aerosmith Big Ones fun Sweet emotion 5:10 Aerosmith Armageddon passion The Age of Love (Jam & Spoon Watch Out For Stella Mix) 4:08 Age of Love The Age of Love adventure Akon, Colby O'Donis, Kardinal Beautiful 5:13 Offishall Freedom Love Do You Love Me 2:16 Amanda Jenssen Killing My Darlings Love Sweet Pea 2:09 Amos Lee Supply and Demand passion Let Love Fly (Joe Claussell's Sacred Rhythm LP Version) 5:46 Ananda Project Night Blossom adventure True Love 6:05 Angels and Airwaves I-Empire love Reckless (With Your Love) 5:42 Azari & iii Defected in the House Ibiza passion Romeo 3:26 Basement Jaxx The Singles love Love Can Do You No Harm 3:04 Beangrowers Not In A Million Lovers adventure Able to Love (Sfaction Mix) 3:27 Benny Benassi & The Biz No Matter What You Do / Able to Love adventure Crazy in Love 3:56 Beyonce Dangerously In Love Love Cradle of love 4:38 Billy Idol Billy Idol: Greatest Hits Love Where is the Love 4:33 Black Eyed Peas Elephunk World needs love Heart of Glass 4:35 Blondie The Best of Blondie relationship I Feel Love 3:13 Blue Man Group & Venus Hum The Complex romance One Love/People Get Ready 3:02 Bob Marley & The Wailers Exodus romance Thank You For Loving Me 5:09 Bon Jovi Crush relationship Somebody to Love (UK Club Mix) 131/65bpm 4:02 Boogie Pimps Somebody to Love CDM romance Copyright © 2012 Indoor Cycling Association -

Games Officially Open

1987 INTERNATIONAL SUMMER ^rVntsPECiAL OLYMPicsfriE’B SPECIAL OLYMPICS ISSUE__________________________ ISSOG Issue Monday, August 3, 1987 - page 1 The Official Publication of the International Summer Special Olympics Games Games officiallyopen By MATT SITZER Observer Staff Sunday was a truly memorable day at the 1987 International Summer Spe cial Olympic Games as they were for mally begun in a gala Opening Ceremonies extravaganza performed before a capacity crowd at Notre Dame Stadium. The Ceremonies were preceded by a full day of exciting competion, as many of the events finished preliminary ac tion and moved into actual competition. When not competing in their respec tive events, athletes took time out to participate in the many interesting clinics and demonstrations taking place at various locations around the Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s cam puses. They certainly had no trouble keeping themselves occupied during their leisure time. Olympic Town was open as usual, highlighted by an apppearance from Miss America, Kelleye Cash. Special Olympians found many other opportu nities to get celebrity autographs and photos, as the “stars” were out in force throughout the many athletic venues. Athletic events weren’t the only things to heat up yesterday, as temper atures soared into the 90’s, making Sun day’s competition sticky indeed. But athletes, coaches, and volunteers didn’t seem to mind the temperature, as they awaited the thrilling Opening The Observer/Fred Dobie Ceremonies with breathless anticipa- Pop singer Whitney Houston prepares to perform her rendition of “Love Will Save the Day.” Appearing with Houston attion. the extravaganza were Barbara Mandrell, John Denver and a host of others. -

G Unit Stunt 101 Gabe Dixon Band Five More Hours Gabriel, Ana

G/j G Unit Stunt 101 Gabe Dixon Band Five More Hours Gabriel, Ana Hablame De Frente Gabriel, Peter Big Time Gabriel, Peter In Your Eyes Gabriel, Peter Lovetown Gabriel, Peter Red Rain Gabriel, Peter Shock The Monkey Gabriel, Peter Sledgehammer Gabriel, Peter Solsbury Hill (Live Version) Gabriel, Peter & Bush, Don't Give Up(Duet) Kate Gabrielle Because Of You Gabrielle Don't Need The Sun To Shine Gabrielle Dreams Gabrielle Forget About The World Gabrielle Give Me A Little More Time Gabrielle Going Nowhere Gabrielle I Wish Gabrielle If I Walked Away Gabrielle If You Ever Gabrielle If You Really Cared Gabrielle Out Of Reach Gabrielle Rise Gabrielle Rise Knocking On Heavens Door Gabrielle Should I Stay Gabrielle Sunshine Gabrielle Walk On By Gabrielle When A Woman Gabrielle When A Woman Gaines, Rosie Surrender Gala Let A Boy Cry Gallagher & Lyle Heart On My Sleeve Gallery Nice To Be With You Game &. 50 Cent Hate It Or Love It Game &. 50 Cent How We Do Game, The Dreams Game, The feat. Ne-Yo Camera Phone Gap Band Big Fun Gap Band Early In The Morning Gap Band Early In The Morning Pt 1 Gap Band Early In The Morning Pt 2 Gap Band Oops Upside Your Head Gap Band Party Train Gap Band You Dropped A Bomb On Me Garbage #1 Crush Garbage Bleed Like Me Garbage I Think I'm Paranoid Garbage Milk Garbage Only Happy When It Rains Garbage Push It Garbage Queer Garbage Special Garbage Stupid Girl Garbage Stupid Girl Garbage When I Grow Up Garbage Why Do You Love Me Garbage You Look So Fine Gardiner, Boris I Want To Wake Up With You Garfunkel, Art Bright Eyes Garfunkel, Art I Only Have Eyes For You Garfunkel, Art Since I Don't Have You Garfunkel, Art Wonderful World Garland, Judy But The World Goes Round Garland, Judy Come Rain Or Come Shine Garland, Judy Get Happy Garland, Judy Man I Love Garland, Judy Man That Got Away Garland, Judy Meet Me In St. -

Songs by Artist

Nice N Easy Karaoke Songs by Artist Bookings - Arie 0401 097 959 10 Years 50 Cent A1 Through The Iris 21 Questions Everytime 10Cc Candy Shop Like A Rose Im Not In Love In Da Club Make It Good Things We Do For Love In Da' Club No More 112 Just A Lil Bit Nothing Dance With Me Pimp Remix Ready Or Not Peaches Cream Window Shopper Same Old Brand New You 12 Stones 50 Cent & Olivia Take On Me Far Away Best Friend A3 1927 50 Cents Woke Up This Morning Compulsory Hero Just A Lil Bit Aaliyah Compulsory Hero 2 50 Cents Ft Eminem & Adam Levine Come Over If I Could My Life (Clean) I Don't Wanna 2 Pac 50 Cents Ft Snoop Dogg & Young Miss You California Love Major Distribution (Clean) More Than A Woman Dear Mama 5Th Dimension Rock The Boat Until The End Of Time One Less Bell To Answer Aaliyah & Timbaland 2 Unlimited 5Th Dimension The We Need A Resolution No Limit Aquarius Let The Sun Shine In Aaliyah Feat Timbaland 20 Fingers Stoned Soul Picnic We Need A Resolution Short Dick Man Up Up And Away Aaron Carter 3 Doors Down Wedding Bell Blues Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Away From The Sun 702 Bounce Be Like That I Still Love You How I Beat Shaq Here Without You 98 Degrees I Want Candy Kryptonite Hardest Thing The Aaron Carter & Nick Landing In London I Do Cherish You Not Too Young, Not Too Old Road Im On The Way You Want Me To Aaron Carter & No Secrets When Im Gone A B C Oh, Aaron 3 Of Hearts Look Of Love Aaron Lewis & Fred Durst Arizona Rain A Brooks & Dunn Outside Love Is Enough Proud Of The House We Built Aaron Lines 3 Oh 3 A Girl Called Jane Love Changes -

Karaoke Usb 2

Page 1 Karaoke USB2 by Artist Track Number Artist Title 1 112 Cupid 2 112 Dance With Me 3 2 Pac California Love 4 2 Pac Changes 5 2 Pac Dear Mama 6 2 Pac Hit Em Up (Explicit) 7 2 Pac How Do You Want It 8 2 Pac I Get Around 9 2 Pac So Many Tears 10 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 11 2 Pac Until The End Of Time 12 3 Dog Night Mama Told Me 13 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 14 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 15 98 Degrees Because Of You 16 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 17 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 18 98 Degrees Invisible Man 19 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 20 A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie 21 A Taste Of Honey Sukiyaki 22 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody 23 Aaliyah At Your Best (You Are Love) 24 Aaliyah Back And Forth 25 Aaliyah Hot Like Fire 26 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 27 Aaliyah I Dont Wanna 28 Aaliyah Journey To The Past 29 Aaliyah Miss You 30 Aaliyah More Than A Woman 31 Aaliyah Music Of The Heart 32 Aaliyah Rock The Boat 33 Aaliyah The One I Gave My Heart To 34 Aaliyah Try Again 35 Aaliyah And Tank Come Over 36 Aaliyah And Timbaland We Need A Resolution 37 Aaron Hall I Miss You 38 Abba Dancing Queen 39 Abba Take A Chance On Me 40 Abba The Winner Takes It All 41 Abba Waterloo 42 Ace Of Base All That She Wants 43 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 44 Ace Of Base Cruel Summer 45 Ace Of Base Dont Turn Around 46 Ace Of Base The Sign 47 Acker Bilk Stranger On The Shore 48 Adina Howard Freak Like Me 49 Aerosmith Amazing 50 Aerosmith Angel 51 Aerosmith Crazy 52 Aerosmith Crying 53 Aerosmith Dont Wanna Miss A Thing 54 Aerosmith Dream On 55 Aerosmith Janies Got A Gun 56 Aerosmith -

Inside Official Singles & Albums • Airplay Charts

ChartPack cover_v2_News and Playlists 02/12/13 12:55 Page 35 CHARTPACK One Direction top the Official UK Artist Albums Chart with Midnight Memories INSIDE OFFICIAL SINGLES & ALBUMS • AIRPLAY CHARTS • COMPILATIONS & INDIE CHARTS 30-31 Singles-Albums_v2_News and Playlists 02/12/13 12:56 Page 28 CHARTS UK SINGLES WEEK 48 For all charts and credits queries email [email protected]. Any changes to credits, etc, must be notified to us by Monday morning to ensure correction in that week’s printed issue Key H Platinum (600,000) THE OFFICIAL UK SINGLES CHART l Gold (400,000) l Silver (200,000) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) +100% sales 0 1 CALVIN HARRIS & ALESSO FT HURTS Under Control Columbia GBARL1301189 (Arvato) 69 6 RIHANNA What Now Def Jam/Virgin USUM71214747 (Arvato) 1 (Harris/Alesso) EMI/Universal (Harris/Hutchcraft/Lindblad) 39 (Ighile/Cassells) Sony ATV/EMI/Universal/BMG Rights/Annarhi/Underground Sunshine/Regime (Waithe/Ighile/Cassells/Fenty) +100% sales 3 2 GARY BARLOW Let Me Go Polydor GBUM71306083 (Arvato) 82 2 JESSIE J Thunder Lava/Republic/Island USUM71311075 (Arvato) 2 (Power) Sony ATV (Barlow) 40 (Stargate/Benny Blanco) Sony ATV/EMI/Warner Tamerlane/Matza Ballzack/Where Da Kasz At/Studiobeast (Cornish/Hermansen/Eriksen/Levin/Kelly) 50% sales 10 5 ONE DIRECTION Story Of My Life Syco GBHMU1300210 (Arvato) 20 11 YLVIS The Fox