Globalization and Development Revealed in Starbucks and Wal-Mart's Business Practices in Shanghai, China : Issues in Restru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 239 05-Jun-2019 7:38:44 State of California Dept. of Alcoholic

05-Jun-2019 State of California Page 1 of 239 7:38:44 Dept. of Alcoholic Beverage Control List of All Surrendered Retail Licenses in MONROVIA District File M Dup Current Type GEO Primary Name DBA Name Type Number I Count Status Status Date Dist Prem Street Address ------ ------------ - -------- ------------- ----------------- -------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------ 20 250606 Y SUREND 02/25/2017 1900 KOJONROJ, PONGPUN DBA: MINI A 1 MART 2 11550 COLIMA RD WHITTIER, CA 90604 61 274544 Y SUREND 04/17/2017 1900 JUAREZ MUNOZ, BARTOLO DBA: CAL TIKI BAR 2 3835 WHITTIER BLVD LOS ANGELES, CA 90023-2430 20 389309 Y SUREND 12/13/2017 1900 BOULOS, LEON MORID DBA: EDDIES MINI MART 2 11236 WHITTIER BLVD WHITTIER, CA 90606 48 427779 Y SUREND 12/04/2015 1900 OCEANS SPORTS BAR INC DBA: OCEANS SPORTS BAR 2 14304-08 TELEGRAPH RD ATTN FREDERICK ALANIS WHITTIER, CA 90604-2905 41 507614 Y SUREND 02/04/2019 1900 GUANGYANG INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT INC DBA: LITTLE SHEEP MONGOLIAN HOT POT 2 1655 S AZUSA AVE STE E HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-3829 21 512694 Y SUREND 04/02/2014 1900 HONG KONG SUPERMARKET OF HACIENDA HEIGHTS,DBA: L HONGTD KONG SUPERMARKET 2 3130 COLIMA RD HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-6301 41 520103 Y SUREND 07/24/2018 1900 MAMMA'S BRICK OVEN, INC. DBA: MAMMAS BRICK OVEN PIZZA & PASTA 2 311 S ROSEMEAD BLVD #102-373 PASADENA, CA 91107-4954 47 568538 Y SUREND 09/27/2018 1900 HUASHI GARDEN DBA: HUASHI GARDEN 2 19240 COLIMA RD ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-3004 41 571291 Y SUREND 12/08/2018 1900 JANG'S FAMILY CORPORATION DBA: MISONG 2 18438 COLIMA RD STE 107 ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-5822 41 571886 Y SUREND 07/16/2018 1900 BOO FACTOR LLC DBA: AMY'S PATIO CAFE 2 900 E ALTADENA DR ALTADENA, CA 91001-2034 21 407121 Y SUREND 06/08/2015 1901 RALPHS GROCERY COMPANY DBA: RALPHS 199 2 345 E MAIN ST ALHAMBRA, CA 91801 05-Jun-2019 State of California Page 2 of 239 7:38:44 Dept. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

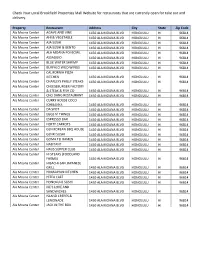

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for Restaurants That Are Currently Open for Take out and Delivery

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for restaurants that are currently open for take out and delivery. Property Restaurant Address City State Zip Code Ala Moana Center AGAVE AND VINE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AHI & VEGETABLE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI & BENTO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ALA MOANA POI BOWL 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ASSAGGIO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BLUE WATER SHRIMP 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BUFFALO WILD WINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CALIFORNIA PIZZA KITCHEN 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHEESEBURGER FACTORY & STEAK & FISH CO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHO DANG RESTAURANT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CURRY HOUSE COCO ICHIBANYA 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center DA SPOT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center EGGS N' THINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ESPRESSO BAR 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center FORTY CARROTS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GEN KOREAN BBQ HOUSE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GENKI SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana -

Executive Summary

1 Executive Summary This paper is a senior comprehensive project written by Alexander Kwong through the Urban Environmental Policy department at Occidental College. The following research attempts to examine the American fast food industry in China in the context of consumerism, industry growth, and cross‐cultural transplantation. Consumers and corporations in China today are both driven to compete and to outmaneuver their competition. This developing neo‐liberal mentality values individualized decision‐making and the flexibility of free enterprise. In a country that has more recently opened itself to foreign commerce, China and its major urban centers have been transformed into hotspots for international business activities in the form of both equity investment, the physical production of goods, and a more American perception of independent consumerism amongst nearly all of China’s socio‐economic classes. The American fast food industry has helped to pioneer foreign corporate investment in China. Well‐known brands, such as KFC and McDonald’s, have flourished in a largely speculative Chinese market that is still confronted by much inconsistency and needed maturation. For example, by achieving significant capital growth and demonstrating the knack for swift adaptation to brand mechanics, KFC, the near unanimous market leader, has quickly become “the single largest restaurant enterprise in China” and has defined for other industries, fast food and beyond, the criteria for successful investment and development in China.1 To put KFC’s accomplishment into better context, China was a nation that was predominately isolated internationally only a mere generation ago. China has indeed come a long way in a very short amount of time. -

Store Openings 21 April

Please note individual store hours may vary to the centres/ are subject to change by the stores. Please contact the individual store directly for any queries. Stores contact details can be searched online at: www.thesquare.ie/shop/ Level 3 Abrakebabra (take-away, delivery) Eddie Rockets(take-away, delivery) Ginzeng(take-away) Boots Burger King (take-away, delivery) Dunnes Stores (Home & selected ranges) Eir Hickeys Pharmacy KFC (take-away, delivery) McDonalds (take-away, delivery) Nando's (take-away, delivery) Sally's Ice Cream Spar Specsavers (by appointment) Starbucks (take-away) Subway (take-away) Tech experts Dentist(by appointment) Chiropodist(by appointment) Family Planning (by appointment) Vodafone Level 2 Argos (click & collect essential items only) Boots Butcher Block Clarks (by appointment 01-4525852) Dunnes Stores Easons EBS Eir Fuji Holland & Barrett Hugmie JD Sports (by appointment 045-810034) Mingles Ice Cream (take-away) Offbeat Donuts (take-away) Skechers (by appointment 01-4626378) Tesco The Carphone Warehouse Three Store Virgin Media Vision Express (appointments) Zenerji (take-away) Level 1 Bookstation Bellarmine Dry Cleaners Dealz Dixon Hempenstall Opticians Euro Giant Ginos Heatons (by appointment) Health Express Insomnia Jackie's Florist (delivery only) Mannings Superdrug Sports Direct (by appointment 1890 800 336) Therapie (by appointment) The Health Store Level 1- External Post Office Costa Coffee (take-away) Dominos (take-away, delivery) Green Steam Auto Spa Just Wing It (delivery) Mao at Home (take-out/deliveries only) The One Asian Kitchen (deliveries only) The Supplement Store WowBurger (take-out/ deliveries). -

Irish Foodservice Market Directory 2020 Download

Irish Foodservice Market Directory 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page IRISH FOODSERVICE MARKET DIRECTORY Introduction 5 How to use the Directory 5 Methodology 6 KEY MACRO TRENDS 7 FOODSERVICE MAP 9 COMMERCIAL CHANNELS 11 QUICK SERVICE RESTAURANTS (QSR) 13 AIL Group 14 Camile Thai 17 Domino’s Pizza 19 Freshly Chopped 23 IPC Europe (Subway®) 25 McDonald’s 27 Supermac’s 29 FORECOURT CONVENIENCE 33 Applegreen 34 Circle K 37 Maxol 40 FULL SERVICE RESTAURANTS (FSR) & PUB GROUPS 43 Avoca 44 Brambles 47 Donnybrook Fair 50 Eddie Rocket’s / Rockets Restaurants 52 Entertainment Enterprise Group 55 Gourmet Food Parlour 56 Fallon & Byrne 59 Happy Pear (The) 62 JD Wetherspoon 64 Michael JFWright Hospitality Group 66 Press Up Entertainment Group 69 Sprout & Co. 72 COFFEE SHOPS 75 Butlers Chocolate Cafés 76 Esquires Coffee House 79 Insomnia 81 Itsa 84 KC Peaches Cafes and Catering 87 MBCC Foods (Ireland) Ltd. T/A Costa Coffee 89 HOTELS 91 Dalata Group PLC 92 Doyle Collection (The) 97 Limerick Strand Hotel 99 O’Callaghan Collection 102 Talbot Collection (The) 105 Tifco Hotel Group 107 Windward Purchasing Ltd. 110 1 Technology 113 Access Procure Wizard 114 Nutritics *NEW 117 Group Purchasing 121 First Choice Purchasing 122 Trinity Hospitality Services 124 LEISURE/EVENTS 127 Feast 128 Fitzers Catering Ltd 130 John Coughlan Catering 133 Masterchefs Hospitality 135 Prestige Catering Ltd 138 With Taste 140 TRAVEL 143 EFG Catering 144 HMSHost Ireland Ltd 147 Irish Ferries 149 Retail inMotion 152 INSTITUTIONAL (COST) CHANNELS 155 BUSINESS & INDUSTRY (B&I) 157 Aramark Northern Europe 158 Artizan Food Co *NEW 160 Brook Foods 162 Compass Group Ireland 164 Corporate Catering Services Limited 166 Food Space 169 Gather & Gather 172 ISS Catering 175 Mount Charles Ireland 177 Q Café Co. -

Irish Foodservice Market Directory

Irish Foodservice Market Directory NOVEMBER 2016 Growing the success of Irish food & horticulture www.bordbia.ie TABLE OF CONTENTS Page IRISH FOODSERVICE MARKET DIRECTORY Introduction 5 How to use the Directory 5 Methodology 6 TOP 10 PRODUCER TIPS FOR BUILDING A SUCCESSFUL FOODSERVICE BUSINESS 7 FOODSERVICE MAP 9 COMMERCIAL CHANNELS 11 QUICK SERVICE RESTAURANTS (QSR) 13 AIL Group 14 Domino’s Pizza 17 Freshly Chopped *NEW 20 McDonald’s 22 SUBWAY® 25 Supermac’s 27 Forecourt Convenience 31 Applegreen 32 Maxol *NEW 34 Topaz 37 FULL SERVICE RESTAURANTS (FSR) & PUB GROUPS 39 Avoca Handweavers 40 Brambles 43 Eddie Rocket’s 46 Entertainment Enterprise Group 49 Gourmet Food Parlour *NEW 53 Itsa 56 JD Wetherspoon 60 Kays Kitchen Ltd 62 Wagamama 65 COFFEE SHOPS 67 bb’s Coffee and Muffins 68 Butlers Chocolate Café 70 Caffè Nero *NEW 72 Esquires Coffee House 75 Insomnia 77 MBCC Foods (Ireland) Ltd. T/A Costa Coffee 79 Quigleys Café, Bakery, Deli 81 HOTELS 83 Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group 84 Dalata Hotel Group PLC 88 Doyle Collection (The) 92 Limerick Strand Hotel 94 Talbot Hotel Group (The) 97 Tifco Hotel Group 99 1 Group Purchasing 103 First Choice Purchasing 104 Trinity Hospitality Services 105 LEISURE/EVENTS 109 Feast 110 Fitzers Catering Ltd 112 JC Catering 115 Masterchefs Hospitality 117 Prestige Catering Ltd 119 Right Catering Company (The) 121 With Taste 123 TRAVEL 127 Aer Lingus Catering 128 EFG Catering 132 Gate Gourmet Ireland 135 HMS Host Ireland Ltd 137 Irish Ferries 139 Rail Gourmet 142 Retail inMotion 144 SSP Ireland 146 INSTITUTIONAL (COST) CHANNELS 149 BUSINESS & INDUSTRY (B&I) 151 ARAMARK Ireland 152 Baxter Storey 154 Compass Group Ireland 156 Corporate Catering Services Limited 158 Gather & Gather 161 KSG 163 Mount Charles Group 165 Premier Dining 167 Q Café Co. -

The Square Level 1

CONTACT Louise Donnelly E: [email protected] T: 01 639 9603 Gareth McKeown E: [email protected] T: 01 639 9396 139 Express Clean 137 128/129 130 115 131 132 138 134 135 136 151 119 120/121 122 115A 152/153 117 ELLE 118 154 unit no tenant unit no 165A tenant 113/114 112 151A Jewellers The Square 165 156 101 Belarmine Dry Cleaners 132 UAE Exchange Entrance from east 156A car park 165B 102 The Scarlet Heifer 133A An Post 110/111 105 104 103 102 101Belarmine KIDS PLAY AREA 162-164 103 Euro 2 133D Dr Acupuncture DRY CLEANERS DRY 106 104 Ginos Ice Cream 134 Ladbrokes 158 TICKETRON 105 DV8 135 Domino’s Pizza 159 160 106 Superdrug 136 Just Wing It 109 108 108/109 Heatons 137 Mao at Home 123 Fat Buddha 110/111 Dealz 138 Leo Burdock 139 Express Clean 124/126 112 The Square Jewellers 113/114 Peter Mark 151 Mannings Bakery 115A The Health Store 152/153 Wild Nail Bar 127 115 Dixon Hempenstall 154 Available (143 sq ft) 156 Jackie’s Florist Oratory of the 117 Vero Moda Holy Family 118 Golden Spiderweb 156A Wild Lash & Brow Bar 158 Available (205 sq ft) 119 Bookstation 159 Healthier Choice 120/121 Health Express 160 Ticketron 122 Elle 162/164 Therapie 123 Fat Buddha 133D 133A 165 Graham O’Sullivan 124/126 Costa 165A Insomnia 127 Oratory of the Holy Family 165B El Gringo 128/129 Wowburger 151A Citizens Information Desk 130 DNG accommodation schedule accommodation 131 SO Nutrition CONTACT Louise Donnelly E: [email protected] T: 01 639 9603 Gareth McKeown E: [email protected] T: 01 639 9396 Entrance from north Luas -

Nycfoodinspectionmyview Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO PHONE NOODLE HOUSE Queens 7188198205 TACO BELL Brooklyn 8605182577 TACO BELL Brooklyn 8605182577 DUNKIN Queens 5167923957 THE BAGEL FACTORY Brooklyn 7187688300 GEE WHIZ Manhattan 2126087200 NEW DOUBLE CHINESE RESTAURANT Queens 7183263661 GYRO EXPRESS Queens 7182781230 QUIJOTE Queens 9293076007 THE INKAN Queens 7184334171 THE INKAN Queens 7184334171 DIG INN Manhattan 2123655060 DIG INN Manhattan 2123655060 ELSA LA REINA DEL CHICHARRON Manhattan 2123041070 EMERALD FORTUNE Brooklyn 7187879517 EMPELLON Manhattan 2128589365 SOUVLAKI GR MIDTOWN Manhattan 2129747482 EL ALTO DELI MEXICAN FOOD Queens 7184561044 BLUESTONE LANE COFFEE Manhattan 2128888848 GOOD JOY Brooklyn 7188588899 Page 1 of 478 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results GRADE A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A Page 2 of 478 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results FRESH KITCHEN Manhattan 2124813500 BARROW STREET ALE HOUSE Manhattan 2126910282 DUNKIN Bronx 6468724159 DOMINO'S Manhattan 2125010200 MILE 17 Manhattan 2127721734 BLAGGARD'S PUB Manhattan 2123822611 BROOKDALE Manhattan 2127912500 PATISSERIE DES AMBASSADES Manhattan 2126660078 BY CHLOE Manhattan 6463584021 YUAN BAO 50 Brooklyn 7184371888 SAKE BAR SATSKO Manhattan 2126140933 HAAGEN-DAZS Queens 3477329954 2 PALMITAS MEXICAN DELI Queens 7188491108 FRANK PIZZERIA Brooklyn 3474350000 NEW GOLDEN CHOPSTICKS Manhattan 2128250314