Getation Can Be Seen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A FLOWER CARPET for ANTWERP Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven Francis

A FLOWER CARPET FOR ANTWERP Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven Francis Strauven Flower carpets have been a tradition in Flanders since the 1950s. As a rule they employ the pattern of an Oriental carpet, a symmetrical composition of geometric or vegetal motifs, punctuated by symbols of the city in question, all of it made of colourful cutflowers, nearly always begonias. Anyone happening to visit Antwerp’s Grote Markt in June 2015 saw something entirely different: not a pastiche of a traditional carpet composed of decapitated flower heads but an original work of art made with living plants, an enormous contemporary painting realized with vivid pigments of flowers and herbs in full bloom. This position is not only a stance regarding the cultural policy of Belgian cities, it is in the first place the presentation of a work of art in its capacity of being a viewpoint. The work of art itself, the flower carpet realized by Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven in 2015 on the Antwerp market square, is presented and interpre- ted as a stance regarding its urban and societal context. The Academy’s Standpunten series (Position papers) contributes to the scientific debate on current social and artistic topics. The authors, members and working groups of the Academy, write in their own names, independently and in full intellectual freedom. The quality of the published studies is guaranteed by the KVAB POSITION PAPERS approval of one or several of the Academy’s classes. 41 b Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts - 2018 A FLOWER CARPET FOR ANTWERP KVAB Press KVAB POSITION PAPERS 41 b Cover photo: Philippe Van Wolputte Cover design: Francis Strauven The drawing of the Palace of the Academies is a reproduction of the original perspective made by Charles Vander Straeten in 1823. -

Van Club Moral Tot Cakehouse Kleine Kroniek Van Kunstenaarsinitiatieven En –Collectieven in Antwerpen (1977-2007)

VAN CLUB MORAL TOT CAKEHOUSE KLEINE KRONIEK VAN KUNSTENAARSINITIATIEVEN EN –COLLECTIEVEN IN ANTWERPEN (1977-2007) 1. Hedendaagse underground ? Studenten leren van hun docenten, maar het omgekeerde geldt ook. Toen Niké Moens, studente theaterkostuumontwerpen aan de Antwerpse academie, vorig jaar in het kader van m’n cursus Actuele Kunst de opdracht kreeg een paper te schrijven over een moderne of hedendaagse artistieke beweging, koos ze resoluut voor ‘hedendaagse Antwerpse underground art’. Daarin schetste ze een circuit dat al enige tijd een rol speelt in de Antwerpse alternatieve scène en verwees ze ondermeer naar Factor 44, Radio Centraal, Scheld’apen en Ultra Eczema. Met ‘underground’, een term ontleend aan de tegencultuur van de late jaren vijftig en de jaren zestig, maar nu duidelijk aan een comeback bezig, referereerde ze aan het feit dat deze scène zich in de marge van het ‘officiële’ kunstgebeuren situeert. Zelf was ik de laatste jaren omwille van mijn doctoraatsonderzoek zowat ondergedoken in de jaren zeventig en de jaren tachtig. Daardoor (en wellicht ook door de vreugdevolle verplichtingen van het prille vaderschap) was mijn blik op de jongste actualiteit enigszins gefragmenteerd. Als bezoeker van de Factor 44, de Scheld’apen en de Placenta- en Frigo-events was me echter wel duidelijk geworden dat er zich naast en tussen het vertrouwde veld van de Antwerpse galerieën en musea een netwerk aan het vormen was van kunstenaars, muzikanten en performers voor wie uitwisseling, samenwerking en interdisciplinariteit een grote betekenis hebben. ‘Alternatieve’ plaatsen als de hierboven vermelde vormen inderdaad, haast letterlijk, tijdelijke knooppunten van dit glijdende landschap, dat ondermeer bevolkt wordt door eenmansorganisaties en tijdelijke collectieven. -

ANNE-MIE VAN KERCKHOVEN BHART#01 ZENO X STORAGE - 8 & 9 September 2012, 1-7 Pm

ANNE-MIE VAN KERCKHOVEN BHART#01 ZENO X STORAGE - 8 & 9 september 2012, 1-7 pm Place is where the mind is (1982) Sfeerbeeld van het leven in en rond het underground kunstenaarsinitiatief “Club Moral”, een ve- reniging die zich gedurende zeven jaar in Borgerhout zou toespitsen op extreme kunstuitingen. De film bestaat vooral uit portretten van mensen in en rond de club. An atmospherical typecast of the life in and around the artist initiative “Club Moral”, an asso- ciation that focused in Borgerhout on extreme forms of art for about seven years. The movie is based on portraits of people in and around the club. Data: 1982, format: Super- 8 film transferred on dvd, duration: 8 min 59 sec, color, sound: DDV, camera: AMVK en Danny Devos, producer: AMVK/ Club Moral Une Légende Dorée (2008) Er is het boek “Les Rideaux et le Décor de la Fenêtre” dat ik in 2005 in Rome kocht en dat werd uitgegeven in Parijs in 1968. Er was het plan om meetkundige hoeken die gemaakt werden door vrouwen in hun interieur, met hun meubels, te linken aan ideale meetkundige figuren zoals de “Gulden Snede”. Er was de drang om deze twee componenten te gebruiken om een zachte con- nectie te maken tussen een erotische aanwezigheid van kleuren en gedempte technieken zoals conté en pastel, om te werken in een algemeen mijmerende atmosfeer, terwijl ik exacte weten- schap vermeng met Frans activisme in het boudoir. Om me dan naar het mystieke te keren, tenslotte bij het libertijnse terecht te komen en het abstracte te weerleggen. -

VOD-Records Internet-Newsletter 01/2012 (

VOD-Records Internet-Newsletter 01/2012 (www.vod-records.com) RELEASES SCHEDULED FOR END FEBRUARY VOD94: JOHN DUNCAN 1st Recordings 1978-85 V1.2 5LP/7“-Box 79,99 € 1978 - 1985 V1.2 First Recordings JOHN =`ijkI\Zfi[`e^j VOD94 DUNCAN (0./$(0/,M(%) John Duncan has been one of the most oustanding, consistently controversial and confrontational, powerful, and compelling masters of experimentation for the last 30 years. His works range from noise to conceptual installations, shortwave-radio to enviromental recordings. Over the years, Duncan has worked on many rewarding collaborations including 'Incoming' with Christoph Heemann, 'Contact' with Andrew McKenzie (of the Hafler Trio), 'Palace of Mind' with Giuliana Stefani, 'Da Sich Die Machtgier' with Asmus Tietchens, 'Nine Suggestions' with Mika Vainio and Ilpo Väisänen, 'Our Telluric Conversation' with Carl Michael von Hausswolff. Other than on his own labels AQM and Allquestions, Duncan has released records on labels such as Touch, Staalplaat, Die Stadt & Heemann's Streamline label. This Box-Set combines all of his Vinyl- and Tape-Releases produced between 1978 and 1985 on his own AQM-Label (Organic 12“, Creed & Nicki 7“, Riot Lp) with music from his 82-85-Tape-Releases Music you finish, Supplement, Move Forward (Pleasure Escape), Brutal Birthday Soundtrack, Phantom and Purge). A Bonus 7“ will be provided with earliest collaboration-recordings from 1978 & 79 performed as Doo-Doettes and CV Massage with artists like Michael Le Donne Bhennet, Dennis Duck, P. Mc Carthy, Fredrik Nilsen, Dennis Duck & Tom Recchion VOD95: JOHN BENDER Memories of mindless mechanical monologues 1976-1985 7LP-Book-like Folder-Set (w.Bonus-7“ for members) 119,99 € This outstanding deluxe Box-Set delivers an excellent and extensive overview of John Benders music-output recorded between 1976-1985 John Bender is without any doubt, the protagonist, if not the inventor of a whole musical-genre known as Cold Minimal Wave/Synth. -

Press Release

ZENO X GALLERY Frank Demaegd Works on paper Dirk Braeckman, Yun-Fei Ji, Kim Jones & Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven February 1, 2013 – March 9, 2013 Wednesday until Saturday: 2 – 6 pm Preview: Thursday January 31: 6 – 8 pm The Belgian artist Dirk Braeckman (°1958, Eeklo) travels along empty and desolated places, abandoned by human beings. Instead of reconstructing a possible storyline or history of the location, his eye is touched by the emptiness or by the present texture of textiles, floors, walls and furniture. Also when a person dominates the scene, Braeckman focuses on the skin and the way light reshapes the body. In black and white tones, he captures the moment where curiosity, registration and desire comes together. The works by Yun-Fei Ji (°1963, Bejing) are closely related to the ancient culture of China. He paints according to traditional Eastern art-making practice and respects centuries old techniques such as calligraphy. With translucent ink or paint based on natural pigments he creates layered images on handmade rice paper. Although the iconography seems very conventional, the content isn’t at all. Yun-Fei Ji reflects on the current situation of China and on the influence of the communism. In ‘Marshal Peng Dehuai and his hungry ghosts’ he depicts the respected Marshal Peng who was the only one criticizing Mao’s ‘Great leap forward’. The works on paper by Kim Jones (°1944, Los Angeles) refer to his performances as Mudman, his alterego. It was arround 1975 he appeared for the first time as Mudman in the streets of LA. For every performance he pulls a nylon panty over his head, covers his body with mud and wears a selfmade construction of wooden sticks on his back. -

Politieke En Sociale Wetenschappen. Aanwinsten Van Anet — Periode 2011/02

Politieke en sociale wetenschappen. UHasselt: 141.7 HUYS 2008 Aanwinsten van Anet — Periode 2011/02 Joseph de Maistre and the legacy of Enlightenment / [edit.] Carolina Armenteros ; [edit.] Richard A. Lebrun. — Politieke en sociale filosofie Oxford : Voltaire Foundation, 2011. — 254 p. — (Studies on Voltaire and the eighteenth century ; 2011: 1). — De aarde warmt op en de geesten verhitten : ecologisme als ISBN 978–0–7294–1008–3 nieuwe machtige religie / Jean-Marie Dedecker. — Leuven : UA–CST: T&L 840 F–VOLT:2011,1 Van Halewyck, 2010. — 216 p. — ISBN 978–94–6131–006–4 UA–CST: PSW 628 G–DEDE 2010 Metaphysische Anfangsgrunde¨ der Rechtslehre / Immanuel EHC: 738607 Kant ; [edit.] Bernd Ludwig. — 2 ed. — Hamburg : Meiner, 1986. — 224 p. — (Metaphysik der Sitten ; 1). — Theory of mind : how children understand others' thoughts and ISBN 3–7873–0692–7 feelings / Martin J. Doherty. — Hove : Psychology Press, UA–CST: HB–RECH–PAVLG 2009. — 247 p., ill. — ISBN 978–1–84169–570–9 ; ISBN 978–1–84169–571–6 UA–CST: FILO 148.2 G–DOHE 2009 Political memoirs / Aurel Kolnai ; [edit.] Francesca Murphy. — Lanham, Md : Lexington Books, 1999. — 252 p. — (Religion, politics, and society in the new millenium ; 1999: 1). — Marx's ecology : materialism and nature / John Bellamy ISBN 978–0–7391–0065–3 Foster. — New York, N.Y. : Monthly Review, 2000. — 310 UA–CST: HB–FIL–LEMMW p. — ISBN 1–58367–012–2 ; ISBN 1–58367–011–4 UA–CST: PSW 141.7 G–FOST 2000 Hegemony and socialist strategy : towards a radical democratic politics / Ernesto Laclau ; Chantal Mouffe. — 2 ed. — London : War and moral dissonance / Peter A. -

VOD-Records Member/Mitglieder-Newsletter 04/2011 (

VOD-Records Member/Mitglieder-Newsletter 04/2011 (www.vod-records.com) Dearest Members/Subscribers, Liebe Mitglieder/Abonnenten, First shipment of 2011 with 6 Wave-Releases ready End April / Beginning of May. Die erste Ladung von 2011 ist End April / Anfang Mai bereit. - TARA CROSS 4LP, - VAN KAYE + IGNIT 5LP (plus 10” for members) - M.A.L. 1LP, - PSYCHE 3LP/7”/DVD - FOCKEWULF 190 2LP (plus 7” for members) - ATTRITION 2Lp Second Delivery with 3 Industrial-releases plus delayed Laibach will follow End June / Mid July Zweite Ladung mit 3 Industrial-Releases und der verspäteten Laibach erscheint Ende Juni / Mitte Juli - LAUGHING HANDS / INVISIBLE COLLEGE 4LP/DVD - GRIM 3LP - GHEDALIA TAZARTES 4LP/DVD (10” for members) - verspätete/delayed LAIBACH 5Lp - Psychic TV-Poster (unfolded with extra-charge) Third Delivery with 2 Industrial-releases plus 1 Wave- Release Mid to End November Dritte Ladung mit 2 Industrial-Releases und 1 Wave-VÖ erscheint Mitte/Ende November - V/A Club Moral 5LP/DVD (plus 7” for members) - Clock DVA 6LP/DVD (plus 7” for members) - John Bender 7LP/DVD (plus 7” for members) INDUSTRIAL-SUB: 5 Releases w. 23 records in 2 shipments (June/ Dec.) (Price Industrial-Sub is 229 Euros plus tax & 2xpostage) CLOCK DVA (6LP+DVD+7“), GRIM (3LP), Ghédalia Tazartès (4LP+10“), LAUGHING HANDS (4LP+DVD), V/A CLUB MORAL (5LP/DVD+7“) WAVE-SUB: 7 Releases, 24 records+bonus (2 shipments April /Dec) (Price Wave/Minimal-Sub 2011 is 239 Euros Tax / 2xPostage) JOHN BENDER (7LP/DVD), VAN KAYE & IGNIT (5LP+10“), M.A.L.(1LP), TARA CROSS (4LP), PSYCHE -

An Exhibition of Fridericianum Kassel. Curated by Anders Kreuger, M HKA Antwerpen

An exhibition of Fridericianum Kassel. Curated by Anders Kreuger, M HKA Antwerpen. The show is the further development of a presentation trilogy that was previously shown in M HKA Antwerp as well as Kunstverein Hanover and Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach. Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven strategically uses her initials as if they were a global corporate brand. She consciously chooses the distanced anonymity for her work, which for more than 40 years has been fed by the cultural inventions of the underground. Graffiti-like drawings are just as much part of her work as shrill music and eccentric performances. AMVK contrasts the proliferation of technological progress and artificial intelligence with the timelessness of human sensations. The starting point of Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s work was and remains the human brain, with its analytical and irrational possibilities of perception and cognition. She was born in 1951 in Antwerp, where she still lives and works. Her work has always been consistently interdisciplinary. She and her partner, the artist Danny Devos, founded the noise band Club Moral in Antwerp in 1981. It existed until 1991 and was revived in 2001. Since 1982, they have been publishing the magazine Force Mental together. Since 1977, AMVK has collaborated with the neuroscientist Luc Steels and since 1982 with his Laboratory for Artificial Intelligence (Brussels, today Paris). As a result, visual languages characterized by scientific imaging processes became prominent in her work: diagrams, graphic animations, text/image compositions. These and other collaborations have always been typical for Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s working method. For her, everything is based on a clear, even merciless commitment to the societal critique that her work seeks to articulate; here the child of 1968 ‘outs’ herself. -

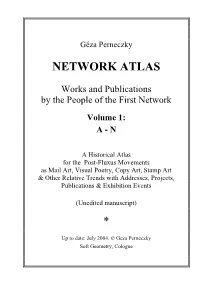

The Network Atlas

Géza Perneczky NETWORK ATLAS Works and Publications by the People of the First Network Volume 1: A - N A Historical Atlas for the Post-Fluxus Movements as Mail Art, Visual Poetry, Copy Art, Stamp Art & Other Relative Trends with Addresses, Projects, Publications & Exhibition Events (Unedited manuscript) * Up to date: July 2004. © Geza Perneczky Soft Geometry, Cologne 2 3 It's very important for me to say that I consider my occupation as an artist as very small and insignificant but at the same time as one of great dignity. I mean the refusal to accept compromisses with power, no matter of what kind it is, and the rejection of the use of art and the artistic work as its instrument... Es muy importante para mí expresar que el ejercicio de mi profesión artística lo veo como una actividad muy modesta, pero con mucha dignidad a la vez. Me refiero a la actitud de rechazo de todo compromiso con el poder, cualquiera que sea, y de la utilización de la actividad creadore como instrumento de él... Es ist für mich sehr wichtig zu sagen, daß ich meine künstlerische Tätigkeit als sehr bescheiden betrachte, gleichzeitig aber als eine von großer Würde. Ich meine damit das Zurückweisen von Kompromissen mit der Macht, egal welcher Art sie ist, und das Zurückweisen der Benutzung der Kunst und der künstlerischen Tätigkeit als ihr Instrument... (Guillermo Deisler: Some events... ) 4 1 a Collective de Arte Postale» Faculdade de Filosofia. Arapongas Brasil 1978 → °1 a Collective de Arte Postale. Doc. List of 29 parts. 1978 «A 1. Waste Paper Comp. -

Pressrelease the Untamed

Press Release The Untamed AMVK (Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven) Sidsel Meineche Hansen Aurel Haize Odogbo Jacolby Satterwhite Will Sheldon Cajsa von Zeipel Curated by Taylor Trabulus August 30 - October 12, 2019 Opening August 29, 6 - 8 pm To tame is to subdue, control and to discipline. It occurs, insidiously, on both conscious and subconscious levels. In the age of techno-capitalism, our bodies undergo this as daily routine – we are invariably tracked, monitored and conditioned. The Untamed aims to reclaim power and control over the evasive techniques made to domesticate us into sanitised oblivion. In order to deconstruct and subvert these systems, the artists in this exhibition explore new configurations between artificial plasticity and physically embodied desire. They push the limitations of the body, relying on forbidden modifications - mutating, layering, stretching, cutting, splitting, splicing, marking, glitching, invading - to escape social expectations and create new complex identities. Celebrating, rather than shaming, a hunger to dismantle normative and essentialist constraints, they lean towards an alien anatomy that is beyond human flesh and bone. The result is a carnal revolution predicated on the limitless possibilities of what our bodies can achieve when freed. The Untamed features works by AMVK(Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven), Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Aurel Haize Odogbo, Jacolby Satterwhite, Will Sheldon and Cajsa von Zeipel and is curated by Taylor Trabulus. The exhibition is on view at Karma International, Zurich from August 30 through October 12, 2019 with an opening reception on August 29. ---- AMVK (Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven) creates techno-fetishistic portraits loaded with philosophical meaning. Working simultaneously in both analogue and digital platforms, she establishes connections between scientific progress and intrinsic human development. -

Anne-Mie V an K Erc Kho

N° 2 FALL-WINTER 2020 WWW.LOFFICIEL.BE Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven Anne-Mie Van Galila Barzilaï-Hollander Gabriel Kuri, Eric Croes, Alice van den Abeele, Dimitri Jeurissen N°2 Fall-Winter 2020 - 9,50 € L’OFFICIEL ART BELGIUM N°02 N°02 L’OFFICIEL ART BELGIUM Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven: Riot girl Interview by Sarah Schug Photographer Mireille Roobaert Kaleidoscopic, hypnotizing animated drawings and photographs dance across a wide screen, flowing into each other in perfect rhythm with throbbing psychedelic soundscapes. Floating from abstract to figurative and back again, the dreamlike sequences are layered with fragments of philosophical text, from thoughts on neural Darwinism and to what extent perception is influenced by personal values to quotes from Nietzsche and Marcuse. Complex, slightly obscure, and definitely thought- provoking, the film is Anne-Mie Van ANNE-MIE VAN KERCKHOVEN: Kerckhoven’s newest work; it’s on view at “I THINK THAT AS AN ARTIST Brussels contemporary art center Wiels as YOU PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE WITHIN THE part of the group show Risquons-Tout, COMMUNITY. IT’S SOMETHING THAT POLITICIANS AND which runs until 10 January. Cerebral and SCIENTISTS FAIL TO visually stunning at the same time, it’s UNDERSTAND.” characteristic of the artist’s extensive oeuvre, which is deeply rooted in counterculture. 126 PORTRAITS FEATURES 127 L’OFFICIEL ART BELGIUM N°02 N°02 L’OFFICIEL ART BELGIUM “For many years, in the 80s, I worked under the acronym AMVK - and the only reason I did that was because I didn’t want people to see right away that I was a woman.” In Van Kerckhoven’s elaborate universe, SARAH SCHUG: It’s been a challenging more open, following our instincts, and less innovative techniques and themes revolving year for everybody, to put it mildly. -

“In Opposition to the Arbitrary, Which Is the Origin of Every Written and Spoken Language, I Have Placed the Unspoken, the Mystic

“In opposition to the arbitrary, which is the origin of every written and spoken language, I have placed the unspoken, the mystic. From despair to ecstasy, that is what the mystic is about now. This is the all-devouring lust for life and love. Unification, not feeling separated from the rest. No ego, no boundaries. Creation becomes one with its creator. I call it the analogue. The analogue versus the arbitrary. The analogue is ritual, evil, mystery, desire, yearning, lust, while the digital is control, technology, sublimation, dependence, cleanliness, transparency. The analogue plus the digital is what humans are about: perspective.” Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven, Some Sort of Manifesto, 2016–17 Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven (also known as AMVK) is an artist of singular complexity. Born in 1951 in Antwerp, where she still lives and works, she has been active since the 1970s as a visual artist, graphic designer and performer. She has always been a pioneer. She should, first and foremost, be considered an artist for the future. AMVK’s practice is truly interdisciplinary. Her first arena was drawing. She has collaborated with cutting-edge scientists for more than 40 years. In 1981, she and the artist Danny Devos founded the noise band Club Moral, which performed actively for ten years. It was revived in 2001. Under the same title, the pair organised numerous events in Antwerp until 1993. They have also published the magazine Force Mental since 1982. Such collaborations aside, self-organisation and self-analysis are fundamental to AMVK’s work. Her creative commitment to artificial intelligence and other contemporary manifestations of mysticism cannot be disentangled from her social thought and political engagement.