Putting Peripheral Poetries on the Map: Helen of Troy Rewritten by Helias Layios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homer's Iliad Via the Movie Troy (2004)

23 November 2017 Homer’s Iliad via the Movie Troy (2004) PROFESSOR EDITH HALL One of the most successful movies of 2004 was Troy, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Brad Pitt as Achilles. Troy made more than $497 million worldwide and was the 8th- highest-grossing film of 2004. The rolling credits proudly claim that the movie is inspired by the ancient Greek Homeric epic, the Iliad. This was, for classical scholars, an exciting claim. There have been blockbuster movies telling the story of Troy before, notably the 1956 glamorous blockbuster Helen of Troy starring Rossana Podestà, and a television two-episode miniseries which came out in 2003, directed by John Kent Harrison. But there has never been a feature film announcing such a close relationship to the Iliad, the greatest classical heroic action epic. The movie eagerly anticipated by those of us who teach Homer for a living because Petersen is a respected director. He has made some serious and important films. These range from Die Konsequenz (The Consequence), a radical story of homosexual love (1977), to In the Line of Fire (1993) and Air Force One (1997), political thrillers starring Clint Eastwood and Harrison Ford respectively. The Perfect Storm (2000) showed that cataclysmic natural disaster and special effects spectacle were also part of Petersen’s repertoire. His most celebrated film has probably been Das Boot (The Boat) of 1981, the story of the crew of a German U- boat during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941. The finely judged and politically impartial portrayal of ordinary men, caught up in the terror and tedium of war, suggested that Petersen, if anyone, might be able to do some justice to the Homeric depiction of the Trojan War in the Iliad. -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

Helen of Troy: She Was Not a Dumb Blonde

HELEN OF TROY A HEROINE IN A MAN’S WORLD! Katerina Ladianou, Classics, OSU Helen is a beautiful woman, some say a Goddess, others say a whore because of her adulterous ways, and she is pursued relentlessly by suitors from all over the ancient world. Homer, Euripides, and Stesichorus all narrate her story, but Homer is the original source in his 2 epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The fairest woman in the world is Helen, the daughter of the King of Sparta Tyndareos and his wife Leda. Their other daughter Clytemnestra is married to Agamemnon. Such is the fame of the beauty of Helen that every young prince craves to marry her. Superhero Theseus abducts her first, but her brothers Castor and Pollux, [both Argonauts, who sailed to Colchis through the Hellespont with Jason on the Ship Argo to get the Golden Fleece], get her back home. So, when suitors from all over Greece assemble in Sparta to ask for her hand, her father Tyndareos, fearing another abduction makes them take an oath to defend whomever he chooses for her husband, and, moreover, that they collectively would punish anyone who tried to abduct Helen. Then Tyndareos chooses Menelaos and he makes him King of Sparta. In the meantime, Goddess Aphrodite sends an image of Helen to Paris of Troy who at the time is out in the fields shepherding his father’s goats; he falls madly in love with Helen, and the rest is history, for love is the strongest force in the whole world! In the Iliad, Paris, a prince of Troy, a city that has accumulated enormous wealth by controlling the flow of merchant shipping through the nearby Hellespont [in what is now NW Turkey; the Dardanelles], abducts Helen. -

Troy Film Study Guide Answers.Pdf

[EBOOK] Download Free Troy Film Study Guide Answers - PDF File Troy Film Study Guide Answers click here to access This Book : READ ONLINE Movie sheets - teacher submitted movie worksheets Movie Worksheet Database . Have a teachers have viewed then subsequently created film guides for. These film sheets have been tested games to help students study. Helen of troy (miniseries) - wikipedia, the free Helen of Troy is a 2003 television miniseries based upon Homer's story of the Trojan War, Study: Homeric scholarship; Homeric Question. Chorizontes; Historicity Helen of troy | readinggroupguides.com HELEN OF TROY is the story of a beautiful woman whose destiny was to be remembered in the entire Discussion Questions; Reading Guide (PDF) Critical Praise Troy film study guide answers Download Farmtrac 300dtc manual.pdf Download Geometric probability answers study guide.pdf Download Exc 500 service manual.pdf Download Allison marine transmission Study guide 6.1 To study cells, Questions. Interactive Question 6.1. Study Guide Author: Administrator Last modified by: Administrator Created Date: A&e s the great gatsby film study guide (answer on a A&E s The Great Gatsby film study guide (Answer on a separate sheet in complete sentences) Author: melissa.wood Created Date: 3/28/2011 6:18:00 PM Other titles: The movie " troy"? or if you're into greek - Sep 14, 2010 Alright, so I was absent while they watched the movie "Troy" in class. I am still responsible for the study guide though. There will be 2 answers for each The odyssey by homer summary - enotes.com commander of the Greeks at Troy, Start your free trial with eNotes to access more than 30,000 study guides. -

Troy Myth and Reality

Part 1 Large print exhibition text Troy myth and reality Please do not remove from the exhibition This two-part guide provides all the exhibition text in large print. There are further resources available for blind and partially sighted people: Audio described tours for blind and partially sighted visitors, led by the exhibition curator and a trained audio describer will explore highlight objects from the exhibition. Tours are accompanied by a handling session. Booking is essential (£7.50 members and access companions go free) please contact: Email: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7323 8971 Thursday 12 December 2019 14.00–17.00 and Saturday 11 January 2020 14.00–17.00 1 There is also an object handling desk at the exhibition entrance that is open daily from 11.00 to 16.00. For any queries about access at the British Museum please email [email protected] 2 Sponsor’sThe Trojan statement War For more than a century BP has been providing energy to advance human progress. Today we are delighted to help you learn more about the city of Troy through extraordinary artefacts and works of art, inspired by the stories of the Trojan War. Explore the myth, archaeology and legacy of this legendary city. BP believes that access to arts and culture helps to build a more inspired and creative society. That’s why, through 23 years of partnership with the British Museum, we’ve helped nearly five million people gain a deeper understanding of world cultures with BP exhibitions, displays and performances. Our support for the arts forms part of our wider contribution to UK society and we hope you enjoy this exhibition. -

Lecture 37 Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology

Lecture 37 Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology. When last we left our heroes, the Homeric heroes of the Trojan War, which was really fought right around 1200 BC, I was discussing the concept of nostos or return home. I was being hassled. I was being haxed. I was being brutalized emotionally and intellectually by somebody who took exception to my remark that nobody actually won the Trojan War. Nobody did. Oh yeah, the Greeks got to sack the city, all right. There’s no denying that. Look at what happened to the Greeks when they went home. Let’s take Agamemnon, for example. What happened to him? He got killed. By who? That is pretty bad. What happened to his wife? Their son killed her. That was all right, because he’d killed her. Nope, he’s no winner. Menelaus—Mr. Helen—he actually did get back together with Helen. He took Helen back. They got on a ship and they were going to sail back to ancient Greece, but they were blown away by a storm and wound up living for seven years in ancient Egypt. I say ancient Egypt because even to the ancient Greeks, ancient Egypt was very, very ancient. Nestor made it home in one piece, too. Does anybody have a guess why Nestor made it home in one piece? Okay, go on and build on that thought, Jeremy. Well, yes and no. Oh, give me a break. Go back home. That isn’t bad. It isn’t right, either. I think, in his heart of hearts, Homer empathized with the old guy who talks just about forever. -

Helen of Troy Chiswick Press:—Charles Whittingham and Co., Tooks Court, Chancery Lane

HELEN OF TROY CHISWICK PRESS:—CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE. “Le joyeulx temps passé souloit estre occasion que je faisoie de plaisants diz et gracieuses chançonnetes et ballades. Mais je me suis mis à faire cette traittié d’affliction contre ma droite nature . et suis content de l’avoir prinse, car mes douleurs me semblent en estre allegées.”—Le Romant de Troilus. To all old Friends; to all who dwell Where Avon dhu and Avon gel Down to the western waters flow Through valleys dear from long ago; To all who hear the whisper’d spell Of Ken; and Tweed like music swell Hard by the Land Debatable, Or gleaming Shannon seaward go,— To all old Friends! To all that yet remember well What secrets Isis had to tell, How lazy Cherwell loiter’d slow Sweet aisles of blossom’d May below— Whate’er befall, whate’er befell, To all old Friends. BOOK I—THE COMING OF PARIS Of the coming of Paris to the house of Menelaus, King of Lacedaemon, and of the tale Paris told concerning his past life. I. All day within the palace of the King In Lacedaemon, was there revelry, Since Menelaus with the dawn did spring Forth from his carven couch, and, climbing high The tower of outlook, gazed along the dry White road that runs to Pylos through the plain, And mark’d thin clouds of dust against the sky, And gleaming bronze, and robes of purple stain. II. Then cried he to his serving men, and all Obey’d him, and their labour did not spare, And women set out tables through the hall, Light polish’d tables, with the linen fair. -

Helen, Daughter of Zeus

Helen, Daughter of Zeus Helen of Troy: Beauty, Myth, Devastation Ruby Blondell Print publication date: 2013 Print ISBN-13: 9780199731602 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2013 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199731602.001.0001 Helen, Daughter of Zeus Ruby Blondell DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199731602.003.0002 Abstract and Keywords This chapter introduces the story of Helen of Troy in Greek mythology: her conception by Zeus, her abduction by Theseus, the oath of the suitors, her marriage to Menelaus, the Judgment of Paris, her abduction by Paris, the Trojan War, and her retrieval by Menelaus, who raised his sword to kill her but dropped it at the sight of her beauty. This narrative is elaborated with attention to the particular concerns of this book, especially gender issues, the question of Helen’s agency in her elopement, and the Greek values underlying the Trojan War (notably guest-friendship). The chapter goes on to describe Helen’s role as a divinity in hero cult, where she was worshiped especially as an iconic figure of the bride. As a cult heroine, she enjoys a posthumous relationship with Achilles, who is the most beautiful and mighty of the Greeks, and as such Helen’s closest male equivalent. The chapter ends with a discussion of Helen’s divine, timeless beauty and the resources for representing it in art and literature. Keywords: Achilles, beauty, Helen of Troy, hero cult, mythology, Trojan War A pretty woman makes her husband look small, And very often causes his downfall. As soon as he marries her then she starts To do the things that will break his heart. -

Unique Perspectives in Etruscan Mythology — Concerning the Causes of the Trojan War

Unique perspectives in Etruscan mythology — concerning the causes of the Trojan War Updated 1.28.13 by Mel Copeland (From “Etruscan Phrases” (http://www.maravot.com/Etruscan_Phrases_a.html) The Etruscans were experts in telling their mythology through murals in their tombs, and the mirrors used by their gentry, sold throughout their known world, from the interior of France to the coasts of the Black Sea and North Africa. Etruscan mirrors were beautifully engraved, recalling details recorded in Greek mythology; however, the Etruscans had a unique view of certain stories, particularly those involving Helen of Troy, with many mirrors devoted to the Trojan War and its heroes. Murals in Etruscan tombs tended to show situations of the underworld, such as the appeal of the three- headed giant Geryon (Etr. Cervn) to the god of the underworld, Hades (Etr. AITA). Seated beside the god is the wife whom Hades abducted, Persephone (Etr. PHERSIPNEI), who is allowed to return to earth once a year, as a herald of the coming of spring. This mural from the Tomb of Orcos shows the three-headed giant Geryon (Etr. CERVN) appealing to AITA (Latin Pluto) on the complaint that Heracles (Etr. HERKLE) had stolen his cattle. The theft was the 10th Labor of Heracles. The names of the characters are important in this mural, particularly that of PHERSIPNEI. We note the suffix “EI” in her name that is also one of two suffixes used in Helen of Troy’s names (ELINAI and ELINEI). The common declension to ELINEI and PHERSIPNEI helps us understand the application of the “EI” suffix, since we can see CERVN is appealing to PHERSIPNEI. -

Whore Or Hero? Helen of Troy's Agency And

WHORE OR HERO? HELEN OF TROY’S AGENCY AND RESPONSIBILITY FROM ANTIQUITY TO MODERN YOUNG ADULT FICTION by Alicia Michelle Dixon A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2017 Approved by _____________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Brad Cook _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Steven Skultety © 2017 Alicia Michelle Dixon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated, in memoriam, to my father, Daniel Dixon. Daddy, I wouldn’t be here without you. You would have sent me to college on the moon, if that was what I wanted, and because of that, you set me up to shoot for the stars. For the past four years, Ole Miss has been exactly where I belong, and much of my work has culminated in this thesis. I know that, if you were here, you would be so proud to own a copy of it, and you would read every word. It may not be my book, but it’s a start. Your pride in me and your devout belief that I can do absolutely anything that I set my mind to have let me believe that nothing is impossible, and your never ending cheer and kindness are what I aspire to be. Thank you for giving me something to live up to. You are missed every day. Love, Alicia iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, and foremost, the highest level of praise and thanks is deserved by my wonderful advisor, Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger. -

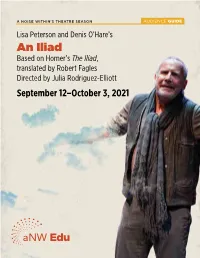

An Iliad Based on Homer’S the Iliad, Translated by Robert Fagles Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott September 12–October 3, 2021 TABLE of CONTENTS

A NOISE WITHIN'S THEATRE SEASON AUDIENCE GUIDE Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare’s An Iliad Based on Homer’s The Iliad, translated by Robert Fagles Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott September 12–October 3, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Maps: An Iliad and The Iliad ................. 3 Synopsis ........................................... 5 About the Author: Homer ............................ 6 About the Adaptors: Denis O’Hare and Lisa Peterson ... 7 History of The Iliad: A Timeline ....................... 9 The Backdrop To The Iliad: Ancient Greece ............ 10 Ancient Oral Poetic Tradition ......................... 11 Greek Mythology: The Role of the Muses .............. 12 Gods, Monsters, and Men in Greek Mythology ......... 13 The Hero’s Journey ................................. 14 Themes ............................................ 16 The Trojan War: Fact or Fiction? ...................... 17 Additional Resources ............................... 18 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T. and Michael J. Connell Eileen L. Norris Foundation Foundation Ralph M. Parsons Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Steinmetz Foundation Coyote Foundation Dwight Stuart Youth Fund The Jewish Community Foundation Cover Image: Geoff Elliott in An Illiad. Photo by Craig Schwartz. 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2021/22 SEASON | Fall 2021 Study Guide An Illiad CHARACTER MAP AN ILIAD Poet A storyteller and a traveler. Plays all of the below roles as he tells the story of the Trojan War. Hermes Greek god, son of Zeus. Appears as a messenger for the Gods. GREEKS TROJANS Agamemnon Priam Hecuba Leader of the Achaean (Greek) army. King of Troy. Father Queen of Troy. Brother to Menelaus and of Hector and Paris. Mother of Hector and brother-in-law to Helen. -

The Natures of Monsters and Heroes

The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research Volume 16 Article 7 2015 The Natures of Monsters and Heroes Vanessa Nikolovska [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Nikolovska, Vanessa. "The Natures of Monsters and Heroes." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 16 (2015): 26-35. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol16/iss1/7>. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol16/iss1/7 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natures of Monsters and Heroes Abstract Around the late eighth or early seventh century B.C., a poet, known to later ages as Homer, composed two epic poems that tell the tales of the Trojan War, The Iliad and The Odyssey. The Iliad tells the story of the rage of Achilles, the great Greek warrior, while The Odyssey tells the story of the coming home of Odysseus, the King of Ithaca, from the Trojan War. A study of both epics reveals that constructs portraying various values, such as the characteristics of heroes, have remained the same from the times of ancient Greece to the present day. However, modern interpretations of ancient Greek epics also portray new/ altered constructs of values in their creation of heroes, such as equality.