32 Gothic Space and the Technological Uncanny In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballard's Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity

Ballard's Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity Item Type Book Chapter Authors Wymer, Rowland Publisher Palgrave Macmillan Download date 04/10/2021 07:04:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/2384/295021 Pre-print copy. For the final version, see: Wymer, R. , 2012. ‘Ballard’s Story of O: “The Voices of Time” and the Quest for (Non)Identity’. In Jeannette Baxter and Rowland Wymer, eds. 2012. J. G. Ballard: Visions and Revisions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ch. 1, pp. 19-34. Chapter One Ballard’s Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity Rowland Wymer ‘The Voices of Time’ (1960) is the finest of Ballard’s early stories, an enigmatic but indisputable masterpiece which marks the first appearance of a number of favourite Ballard images (a drained swimming-pool, a mandala, a collection of ‘terminal documents’) and prefigures the ‘disaster’ novels in its depiction of a compulsively driven male protagonist searching for identity (or oblivion) within a disturbingly changed environment. Its importance to Ballard himself was confirmed by its appearance in the title of his first collection of short fiction, The Voices of Time and Other Stories (1962), and by his later remark that it was the story by which he would most like to be remembered.1 It was first published in the October 1960 issue of the science fiction magazine New Worlds alongside more conventional SF stories by James White, Colin Kapp, E. C. Tubb, and W. T. Webb. This was three-and-a-half years before Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the magazine and inaugurated the ‘New Wave’ by aggressively promoting self- consciously experimental forms of speculative fiction. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Baudrillard's Bastards: 'Pataphysics After the Orgy

SEMIOPHAGY: JOURNAL OF PATAPHYSICS VOL. III, WINTER, 2010 AND EXISTENTIAL SEMIOTICS Baudrillard’s Bastards: ’Pataphysics After the Orgy – Some Lessons for Journalists Peter Hulm Most thinkers write badly because they tell us not only their thoughts but also the thinking of the thoughts. – Nietzsche (1878), Human, All Too Human, Aphorism 188. The Invisible Philosopher Let’s start with the ‘pataphysian himself: • The consumer “no more ‘believes' in advertising than the child believes in Father Christmas, but this in no way impedes his capacity to embrace an internalized infantile situation, and to act accordingly” (1968/2005:182). • “Information is directly destructive of meaning and signification” (1981b/1994:79). • “The Gulf War did not take place” (1991/1995). 1 SEMIOPHAGY: JOURNAL OF PATAPHYSICS VOL. III, WINTER, 2010 AND EXISTENTIAL SEMIOTICS From his earliest writings Jean Baudrillard has been a media provocateur of such Nietzschean brilliance that it has blinded many theorists to the depth and originality of his critique of the news business and television in the DisInformation Age. In addition to smarting at his accurate and aphoristic barbs about current affairs production, mainstream media feels even stronger resentment at his dismissal of the industry’s claims to be a major force in shaping public consciousness. For Baudrillard, scientific jargon, Wall Street, disaster movies and pornography have deeper impact on our imaginations than the news industry. Television and written media, he wrote in 1970, have become narcotic and tranquilizing for consumers in their daily servings of scary news and celebrity fantasies. Only 9/11, he later declared with his usual withering acerbity, has been able to break through the non- event barrier erected by media to the world (2001).1 To recognize the accuracy of Baudrillard’s daily observations, therefore, it is no surprise that we need to turn to a financial statistician, Nassim Nicholas Taleb. -

"Resurrected from Its Own Sewers": Waste, Landscape and the Environment in JG Ballard's Climate Novels Set in Junky

"Resurrected from its own sewers": Waste, landscape and the environment in JG Ballard's climate novels Set in junkyards, abandoned waysides and disaster zones, J.G. Ballard’s fiction assumes waste to be integral to the (material and symbolic) post-war landscape, and to reveal discomfiting truths about the ecological and social effects of mass production and consumption. Nowhere perhaps is this more evident than in his so- called climate novels, The Drowned World (1962), The Drought (1965), originally published as The Burning World, and The Crystal World (1966)—texts which Ballard himself described as “form[ing] a trilogy.” 1 In their forensic examination of the ecological effects of the Anthropocene era, these texts at least superficially fulfil the task environmental humanist Kate Rigby sees as paramount for eco-critics and writers of speculative fiction alike: that is, they tell the story of our volatile environment in ways that will productively inform our responses to it, and ultimately enable “new ways of being and dwelling” (147; 3). This article explores Ballard’s treatment of waste and material devastation in The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World, focussing specifically on their desistance from critiquing industrial modernity, and their exploitation, instead, of the narrative potential of its deleterious effects. I am especially interested in examining the relationship between the three novels, whose strikingly similar storylines approach ecological catastrophe from multiple angles. To this end, I refrain from discussing Ballard’s two other climate novels, The Wind from Nowhere (1962), which he himself dismissed outright as a “piece of hackwork” he wrote in the space of a day, and Hello America (1981), which departs from the 1960s texts in its thematic structure (Sellars and O’Hara, 88). -

Ballard, Smithson, and the Biophilosophy of the Crystal Aidan

Ballard, Smithson, and the Biophilosophy of the Crystal Aidan Tynan (Cardiff University) 1. Landscapes of Spatiotemporal Crisis How should ecocriticism proceed when considering the apocalyptic landscapes of Ballard’s early tetralogy? The Wind from Nowhere (1962), The Drowned World (1962), The Drought (1964), and The Crystal World (1966) provide scenarios in which small groups of survivors struggle to adapt to radical and destructive environmental changes. While we can position these novels broadly within the disaster tradition of British science fiction as represented by John Wyndham, John Christopher and others, they stand apart from this field by featuring characters who accept their fate with unusual resignation, almost apathy. Ballard’s language often reflects the cold detachment of scientific discourse, but no technological fixes emerge in these narratives to resolve the respective ecological crises of devastating winds, melting icecaps, desertification, and the crystallisation of matter. Whatever heroism Ballard’s protagonists possess is to be found in their willingness to embrace the challenges posed by the catastrophe and attain a state of mind adequate to it. The dominant trend in scholarship (Pringle 1984; Luckhurst 1997; Francis 2011) has been to follow Ballard’s own lead and to regard these landscapes as symbolic manifestations of psychological states or external realisations of ‘inner space’, but an ecocritical analysis cannot be satisfied with this. Indeed, it is increasingly difficult not to read these works ecologically and materially and in relation to our own climate emergency. An alternative trend has thus emerged in recent years showing an eagerness to attribute to Ballard a prescience with respect to concerns about environmental change. -

Apocalypse Now: Covid-19 and the SF Imaginary

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 2020 Apocalypse Now: Covid-19 and the SF Imaginary Gerry Canavan Jennifer Cooke Caroline Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/english_fac Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Apocalypse Now: Covid-19 and the SF Imaginary Gerry Canavan, Jennifer Cooke and Caroline Edwards in conversation with Paul March-Russell The following conversation was conducted via Google Docs between 1st May and 23rd June 2020. The participants were Gerry Canavan (Marquette University), Jennifer Cooke (Loughborough University) and Caroline Edwards (Birkbeck College, London). Gerry is President of the SFRA; his books include Green Planets: Ecology and Science Fiction (2014), co-edited with Kim Stanley Robinson, Octavia E. Butler (2016), and most recently The Cambridge History of Science Fiction (2019), co-edited with Eric Carl Link. Jennifer is a poet and academic; her first book was on Legacies of Plague in Literature, Theory, and Film (2009) while her most recent is Contemporary Feminist Life-Writing: The New Audacity (2020). Caroline’s books include Utopia and the Contemporary British Novel (2019) and, with Tony Venezia, China Miéville: Critical Essays (2015); she is also editor of Alluvium and co-founder with Martin Eve of the Open Library of Humanities. Paul March-Russell: Can I ask, how have you all been coping during the pandemic? My responses have ranged from anxiety to acceptance, probably spurred-on by having a very busy household. Yet at the same time there’s no one, universal experience, so how has it been for you? Jennifer Cooke: As an academic, with a house and a garden, I am privileged and I already spend a lot of time working from home or in libraries so that was not a challenge. -

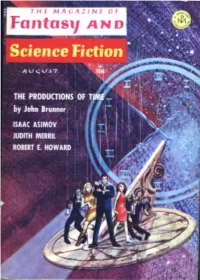

This Month's Issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction

Including Venture Science Fiction NOVEL The Productions of Time (1st of 2 parts) JOHN BRUNNER 4 SHORT STORIES Matog JOAN PATRICIA BASCH 45 The Seven Wonders of the Universe MOSE MALLETTE 70 For the Love of Barbara Allen ROBERT E. HOWARD 82 A Matter of Organization FRANK BEQUAERT 91 Near Thing ROBIN SCOTT 99 Come Lady Death PETERS. BEAGLE 114 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 44 Books JUDITH MERRIL 57 Meteroid Collision THEODORE L. THOMAS 89 Letter to A Tyrant King (verse) BILL BUTLER 90 Science: BB Or Not BB, That Is the Question- ISAAC ASIMOV 103 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by Gray Morrow (illustrating "The Productiom of Time") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Edward L. Ferman, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT. EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. Mills, CONSULTING EDITOR Dale Beardale, CIRCULATION MANAGER The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volume 31, No. 2, Whole No. 183, Aug, 1966. Published monthly by Mercury Press(;Inc., at 50; a copy. Annual subscription 15.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American nion, $6.00 in all other countJ·ies. PubllcatiOfl office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. H. 03301. Editorial and general mail should be setd to 341 East 5Jrd St., New York, N. Y. lOOZZ. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. @ 1966 by Mercury Press, Inc. All rights including translatio1ts into other languages, reserved. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed envelopes; tile Publisher assumcs no re$/>o11sibility for return of unsolicited mallltscripts. That the antics of lunatics can provide some unusual theatrical ef· fects was recently demonstrated in a play by Peter Weiss ("Marat/ Sade")-a play based on the fact that the inmates of Charenton Asylum did perform "therapeutic" theatrical entertainments (in the early 1800's) which were, in fact, devised and directed by the notori ous Marquis De Sade (himself an inmate). -

Judith Merril: a Primary and Secondary Bibliography

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works English and Technical Communication 01 Dec 2006 Judith Merril: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography Elizabeth Cummins Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/eng_teccom_facwork Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cummins, Elizabeth. "Judith Merril: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography." College Station, Texas, Cushing Library, Texas A & M: The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy, 2006. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. -

0278.1.00.Pdf

CRITIQUE OF FANTASY, VOL. II Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contributions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our adventure is not possible without your support. Vive la open access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) Laurence A. Rickels CRITIQUE OF FANTASY VOLUME 2 The Contest between B-Genres Brainstorm Books Santa Barbara, California critique of fantasy, vol. 2: the contest between b-genres. Copyright © 2020 Laurence A. Rickels. This work carries a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform, and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors and editors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2020 by Brainstorm Books An imprint of punctum books, Earth, Milky Way https://www.punctumbooks.com isbn-13: 978-1-953035-18-9 (print) isbn-13: 978-1-953035-19-6 (epdf) doi: 10.21983/P3.0278.1.00 lccn: 2020939532 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J. -

The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard Free

FREE THE COMPLETE STORIES OF J. G. BALLARD PDF J. G. Ballard,Martin Amis | 1216 pages | 21 Sep 2009 | WW Norton & Co | 9780393072624 | English | New York, United States The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard (Hardcover) | Porter Square Books Back to the "Collecting J. Ballard" Home Page. I have The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard the same approach to collections of Ballard's short stories as for his novels. That is, I have listed both U. I have also listed a small number of other editions that are of particular interest. Where a collection was first published in paperback format, it may well have been re- printed by the same publisher at a later date. Usually, the re- print will be recognizable because the artwork on the front cover will be completely different from the first printing. For details of which stories were included in each collection, see here. The first collection of Ballard's short stories, whose only publication was in a U. There was a later reprintwhich had a completely different cover. Note that the title The Voices of Time was used for an entirely different U. A second collection from Berkley inagain only ever issued as a U. The first collection published in the U. The first edition was a hardback from Gollancz inand contained eight stories, of which two including 'The Voices of Time' had appeared in the U. A second edition appeared from Gollancz in with two stories being changed; this later version now contained three stories in common with The Voices of Time and Other Stories. -

Volume 1 Issue 2

FANTASTIKA Fantastika Journal | Volume 1 | Issue 2 | December 2017 EDITOR’S NOTE “Fantastika” – a term appropriated from a range of Slavonic languages by John Clute – embraces the genres of Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror, but can also include Alternative Histories, Gothic, Steampunk, Young Adult Dystopian Fiction, or any other radically imaginative narrative space. The third annual Fantastika conference – Global Fantastika – held at Lancaster University, UK on July 4 & 5, 2016, considered a range of Global topics: productions of Fantastika globally; themes of contact within and across nations and borders; fictional and real empires; themes of globalization and global networks, mobilities, and migrations; and (post)colonial texts and readings, including no- tions of the ‘other.’ Some of the articles in this second issue of Fantastika Journal originate from the conference. The issue also includes articles and reviews from a range of international scholars, some of which are inspired by this Global theme. We are especially pleased to feature editorials from all of the keynotes speakers of the Global Fantastika conference. We hope this special Fantastika issue will stimulate discussion and contemplation of topics that are becoming so crucial and imperative in the world today, as we become a truly global community. Charul (Chuckie) Palmer-Patel HEAD EDITOR 1 Fantastika Journal | Volume 1 | Issue 2 | December 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS HEAD EDITOR Charul (Chuckie) Palmer-Patel CRITICAL CO-EDITORS AND NON-FICTION REVIEWS EDITORS Francis Gene-Rowe, Donna Mitchell FICTION AND NON-FICTION REVIEWS EDITOR Kerry Dodd ASSISTANT FICTION REVIEWS EDITORS Antonia Spencer, Monica Guerrasio DESIGN EDITOR AND COVER DESIGNER Sing Yun Lee CURRENT BOARD OF ADVISERS (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) Xavier Aldana Reyes Brian Baker Sarah Dillon Matt Foley Veronica Hollinger Rob Maslen Lorna Piatti-Farnell Adam Roberts Catherine Spooner Sherryl Vint We would also like to thank our peer reviewers and board of advisors for their kind consideration and efforts with this issue. -

Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex McAulay A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Pamela Cooper María DeGuzmán Kimball King Julius Raper Linda Wagner-Martin © 2008 Alex McAulay ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ALEX MCAULAY: Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film (Under the direction of Pamela Cooper) This dissertation presents an analysis of posthuman texts through a discussion of posthuman landscapes, bodies, and communities in literature and film. In the introduction, I explore and situate the relatively recent term "posthuman" in relation to definitions proposed by other theorists, including N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway, Judith Halberstam and Ira Livingston, Hans Moravec, Max More, and Francis Fukuyama. I position the posthuman as being primarily celebratory about the collapse of restrictive human boundaries such as gender and race, yet also containing within it more disturbing elements of the uncanny and apocalyptic. My project deals primarily with hybrid texts, in which the posthuman intersects and overlaps with other posts, including postmodernism and postcolonialism. In the first chapter, I examine the novels comprising J.G. Ballard's disaster series, and apply Bakhtin's theories of hybridization, and Deleuze and Guattari's notions of voyagings, becomings, and bodies without organs to delineate the elements that constitute a posthuman landscape.