Alchemy and Experiment in the Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

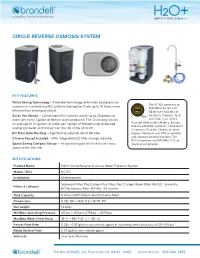

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Bull. Hist. Chem. 13- 14 (1992-93)

ll. t. Ch. 13 - 14 (2 2 tr nnd p t Ar n lt nftr, vd lfr, th trdtnl prnpl f ltn r ldf qd nn ft n pr plnr nd fx vlttn, tn, rprntn "ttr." S " xt Alh", rfrn prnd fr t rrptn." , pp. 66, 886. 25. Ibid., p. 68: "... prpr & xt lnd n pr 4. W. n, "tn Clavis Str Key," Isis,1987, tll t n ..." 78, 644. 26. W. n, The "Summa perfectionis" of pseudo-Geber, 46. hllth, Introitus apertus, BCC, II, 66, "... lphr xtr dn, , pp. 42. n ..." 2. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , pp. 224. 4. frn 4, pp. 24. 28. [Ern hllth,] Sir George Ripley's Epistle to King 48. bb, Foundations , rfrn , p. 28. Edward Unfolded, MS. Gl Unvrt, rn 8, pp. 80, 4. l, " xt Alh", rfrn , p. 64. p. 0. bb, Foundations, rfrn , pp. 22222. 2. MS. rn 8, p. Cf. l Philalethes,Introitusapertus, . Wtfll, Never at Rest, rfrn 8, p. 8. in Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, n Mnt, rfrn 2, l. II, p. 2. r t ll b fl t v bth tn prphr 664. (Cbrd Unvrt brr, Kn MS. 0, f. 22r nd th 30. Ibid., MS. rn 8, pp. 2. rnl (hllth, Introitus apertus, in Bibliotheca chemica curi- 31. Ibid. osa, l. II, p. 66: 32. Ibid., pp. 6. Newton: h t trr prptr ltn , t 33. Ibid. nrl trx prptr nrl n p ltntr, t 4. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , p. 20. tn r vltl, t l [lphr] n tr rvlvntr . [Ern hllth,] Sir George Riplye' s Epistle to King ntnt n ntr , d ntr tt t & trrn d Edward Unfolded, n Chymical, Medicinal, and Chyrurgical AD- prf llnt. -

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation Is the Next Step in Conventional Filtration Plants

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation is the next step in conventional filtration plants. (Direct filtration plants omit this step.) The purpose of sedimentation is to enhance the filtration process by removing particulates. Sedimentation is the process by which suspended particles are removed from the water by means of gravity or separation. In the sedimentation process, the water passes through a relatively quiet and still basin. In these conditions, the floc particles settle to the bottom of the basin, while “clear” water passes out of the basin over an effluent baffle or weir. Figure 7-5 illustrates a typical rectangular sedimentation basin. The solids collect on the basin bottom and are removed by a mechanical “sludge collection” device. As shown in Figure 7-6, the sludge collection device scrapes the solids (sludge) to a collection point within the basin from which it is pumped to disposal or to a sludge treatment process. Sedimentation involves one or more basins, called “clarifiers.” Clarifiers are relatively large open tanks that are either circular or rectangular in shape. In properly designed clarifiers, the velocity of the water is reduced so that gravity is the predominant force acting on the water/solids suspension. The key factor in this process is speed. The rate at which a floc particle drops out of the water has to be faster than the rate at which the water flows from the tank’s inlet or slow mix end to its outlet or filtration end. The difference in specific gravity between the water and the particles causes the particles to settle to the bottom of the basin. -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art BY I. BERNARD COHEN TN seeking for a subject for this paper, it had seemed to me J- that it might prove valuable to discuss certain aspects of our American culture from the vantage point of my own speciality as historian of science and to illustrate for you the way in which the study of the history of science may provide new emphases in American cultural history—sometimes considerably at variance with established interpretations. American cultural history has, thus far, been written largely with the history of science left out. I shall not go into the reasons for that omission—they are fairly obvious in the light of the youth of the history of science as a serious, independent discipline. This subject enables us to form new ideas about the state of our culture at various periods, it casts light on the effects of American creativity upon Europeans, and it focuses attention on neglected figures whose value is appreciated abroad but not at home. For example, our opinion of American higher education in the early nineteenth century is altered when we discover that at Harvard and elsewhere the amount of required science and mathematics was exactly three times as great as it is today in an "age of science."^ In the eighteenth century when, according to Barrett Wendell, Harvard gave its » See "Harvard and the Scientific Spirit," Harvard Alumni Bull, 7 Feb. 1948. 3O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, students only "a fair training in Latin -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Newton the Alchemist Had Been Transmuted Into Newton the Enlightenment Chemist

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. ONE The Enigma of Newton’s Alchemy The Historical Reception hen Isaac Newton died in 1727, he had already become an icon of reason in an age of light. The man who discovered the laws governing gravitational attraction, who unveiled the secrets of Wthe visible spectrum, and who laid the foundations for the branch of math- ematics that today we call calculus, was enshrined at Westminster Abbey alongside the monarch who had ruled at his birth. Despite having been born the son of a yeoman farmer from the provinces, Newton was eulogized on his elaborate monument as “an ornament to the human race.” Perhaps play- ing on the illustrious physicist’s fame for his optical discoveries, the most cel- ebrated English poet of his age, Alexander Pope, coined the famous epitaph “Nature and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night. God said, Let Newton be! and All was Light.” 1 Thus God’s creation of Newton became a secondfiat lux and the man himself a literal embodiment of the Enlightenment. Little did Pope know that in the very years when Newton was discover- ing the hidden structure of the spectrum, he was seeking out another sort of light as well. The “inimaginably small portion” of active material that gov- erned growth and change in the natural world was also a spark of light, or as Newton says, nature’s “secret fire,” and the “material soule of all matter.”2 Written at the beginning of a generation- long quest to find the philosophers’ stone, the summum bonum of alchemy, these words would guide Newton’s private chymical research for decades. -

CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 1/15

CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 1/15 Water Treatment Water Treatment Water treatment describes those industrial-scale The goal of all water treatment process is to processes used to make water more acceptable remove existing contaminants in the water, or for a desired end-use. reduce the concentration of such contaminants so These can include use for drinking water, industry, the water becomes fit for its desired end-use. medical and many other uses. One such use is returning water that has been used back into the natural environment without adverse ecological impact. Water Treatment Water Treatment Basis water treatment consists Coagulation of four processes: This process helps removes Coagulation/Flocculation particles suspended in water. Sedimentation Chemicals are added to water to form tiny sticky particles Filtration called "floc" which attract the Disinfection particles. Water Treatment Water Treatment Flocculation Sedimentation Flocculation refers to water The heavy particles (floc) treatment processes that settle to the bottom and the combine or coagulate small clear water moves to filtration. particles into larger particles, which settle out of the water as sediment. CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 2/15 Water Treatment Water Treatment Filtration Disinfection The water passes through A small amount of chlorine is filters, some made of layers of added or some other sand, gravel, and charcoal disinfection method is used to that help remove even smaller kill any bacteria or particles. microorganisms that may be in the water. Water Treatment Water Treatment 1. Coagulation 1. Coagulation - Aluminum or iron salts plus chemicals 2. Flocculation called polymers are mixed with the water to make the 3. -

Membrane Filtration

Membrane Filtration A membrane is a thin layer of semi-permeable material that separates substances when a driving force is applied across the membrane. Membrane processes are increasingly used for removal of bacteria, microorganisms, particulates, and natural organic material, which can impart color, tastes, and odors to water and react with disinfectants to form disinfection byproducts. As advancements are made in membrane production and module design, capital and operating costs continue to decline. The membrane processes discussed here are microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), and reverse osmosis (RO). MICROFILTRATION Microfiltration is loosely defined as a membrane separation process using membranes with a pore size of approximately 0.03 to 10 micronas (1 micron = 0.0001 millimeter), a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of greater than 1000,000 daltons and a relatively low feed water operating pressure of approximately 100 to 400 kPa (15 to 60psi) Materials removed by MF include sand, silt, clays, Giardia lamblia and Crypotosporidium cysts, algae, and some bacterial species. MF is not an absolute barrier to viruses. However, when used in combination with disinfection, MF appears to control these microorganisms in water. There is a growing emphasis on limiting the concentrations and number of chemicals that are applied during water treatment. By physically removing the pathogens, membrane filtration can significantly reduce chemical addition, such as chlorination. Another application for the technology is for removal of natural synthetic organic matter to reduce fouling potential. In its normal operation, MF removes little or no organic matter; however, when pretreatment is applied, increased removal of organic material can occur. -

Water Filtration Background

Water Filtration Background Water Filtration It's a modern-day engineering challenge to remove human-made contaminants from drinking water. After a quick review of the treatment processes that municipal water goes through before it comes from the tap you will learn about the still-present measurable contamination of drinking water due to anthropogenic (human-made) chemicals. Substances such as prescription medication, pesticides and hormones are detected in the drinking water supplies of American and European metropolitan cities. The engineering design process can be used to design solutions for a real-world problem (contaminated water) that could affect health. Engineering Connection The water that comes from our faucets has passed through a complex system designed by many different types of engineers. Civil, chemical, electrical, environmental, geotechnical, hydraulic, structural and architectural engineers all play roles in the design, development and implementation of municipalities' drinking water supplies and delivery systems. Hydraulic engineers design systems that safely filter the water at a rate needed to supply a specific region and population. Chemical engineers precisely determine the amounts and types of chemicals added to source water for coagulation and decontamination to make the water safe to drink and not taste bad. Even so, modern pharmaceutical and agricultural practices persist in contaminating our water supplies. 1 Water Filtration Background Treating the Public Water Supply: What Is In Your Water, and How Is It Made Safe to Drink? Human Use of Freshwater Humans' Need for Clean Freshwater Water is perhaps the most important nutrient in our diets. In fact, a human adult needs to drink approximately 2 liters (8 glasses) of water every day to replenish the water that is lost from the body through the skin, respiratory tract, and urine. -

Oil Water Separators

27 OilOil WaterWater SeparatorsSeparators This section will cover coalescing oil/water separation. The concept of a basic gravity oil/water separator is simply a tank vessel that stalls the flow rate to permit gravity to separate oil from water. Oil, having a lower specific gravity than water, will naturally float on water if given time to separate. Oil The rise rate of oil to the surface is determined by Stoke’s Law. There are three main factors affect- ing the rise rate: oil droplet size, oil specific gravity and temperature. Other factors include oil/dirt particles and flow rate or turbulence. According to Stoke’s Law, a 100 micron size oil droplet will rise three inches in five minutes. When factoring in a flow rate, you can see how a simple oil/water separator will have to be quite large to give the oil enough time to rise to the surface. A 20 micron size oil droplet will rise three inches in 60 minutes. Large oil droplets are more buoyant and, there- fore, rise faster. Water Oil Layer In order to reduce the physical size of the oil/water sepa- rator, coalescors have been used successfully for many years. The concept of a coalescor is to use oleophillic (oil Oily Water Clean Water loving) media such as polypropylene or teflon. As oil and water flow through the media, oil droplets impinge on the media and coalesces on the surface. Coalescing, or bind- ing together, makes them larger and more buoyant. As Settled Solids Water you can see from the above example, a 100 micron oil particle will rise three inches twelve times faster than a 20 micron particle. -

Redgrove Alchemy Ancient An

kansas city public library Books will be issued only on presentation of library card. Please report lost cards and change of residence promp" ^ard holders are responsible for all books, records, films, pictures ALCHEMY: ANCIENT AND MODERN PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. -

V61-I3-02-Rudrum.Pdf (76.64Kb)

REVIEWS 193 Its sexually-charged and masculine language (of undressing, pierc- ing, scattering) calls into question West’s description of the poem as a “curiously prim meditation on the nuptials of Jacob’s father,” as the wording of that description fails to take into account the significance of the marriage of Isaac in biblical typology. Jean Daniélou’s From Shadows to Reality appears in West’s bibliography, and might have been usefully drawn upon in discussion of “Isaacs Marriage.” In general, however, this book is so enlivening to read because its author has clearly made good use of, and enjoyed, his opportu- nity for research. I liked especially his exposition of the evidence that Royalists connected Charles Stuart, who was crowned King of Scotland in 1651, with the suffering Jacob. The Stone of Des- tiny was thought to be the same one on which Jacob had slept at Bethel. That Charles could not sit on it at his coronation, because it had been removed to Westminster in 1297, would, West sug- gests, have symbolized to Vaughan the disturbance of the patriar- chal line from Jacob’s day. Whatever particular reservations one might have, West’s discussion of Vaughan’s meditation on the pa- triarchs, and their relevance to contemporary Anglican sufferings, is an important contribution to understanding. Donald R. Dickson, ed. Thomas and Rebecca Vaughan’s Aqua Vitæ: Non Vitis (British Library MS, Sloane 1741). Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2001. liii + 270 pp. $35.00 Review by ALAN RUDRUM, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY. Insofar as modern students of literature are aware of Thomas Vaughan (1621-1666), it is as the twin brother of the poet Henry Vaughan.