The Divine and Miss Johanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

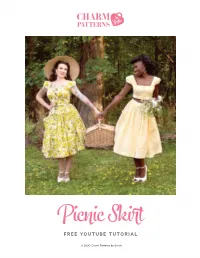

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL © 2020 Charm Patterns by Gertie SEWING INSTRUCTIONS NOTES: This style can be made for any size child or adult, as long as you know the waist measurement, how long you want the skirt, and how full you want the skirt. I used 4 yards of width, which results in a big, full skirt with lots of gathers packed in. You can easily use a shorter yardage of fabric if you prefer fewer gathers or you’re making the skirt for a smaller person or child. Seam Finishing: all raw edges are fully enclosed in the construction process, so there is no need for seam finishing. Make a vintage-inspired button-front skirt without 5/8-inch (in) (1.5 cm) seam allowances are included on all pattern pieces, except a pattern! This cute design where otherwise noted. can be made for ANY size, from child to adult! Watch CUT YOUR SKIRT PIECES my YouTube tutorial to see 1. Cut the skirt rectangle: the width should be your desired fullness (mine is how it’s done. You can find 4 yards) plus 6 in for the doubled front overlap/facing. The length should be the coordinating top by your desired length, plus 6 in for the hem allowance, plus 5/8 in for the waist seam subscribing to our Patreon allowance. at www.patreon.com/ Length: 27 in. gertiesworld. (or your desired length) Length: + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance xoxo, Gertie 27 in. Cut 1 fabric (or your + desired length) ⅝ in waist seam + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance Cut 1 fabric MATERIALS + & NOTIONS ⅝ in waist seam • 4¼ yds skirt fabric (you Width: 4 yards (or your desired fullness) + 6 in for front overlap may need more or less depending on the size and Length: 27 in. -

Street Stylers Nailing This Summer’S Key Trends

STYLE KIM: There’s something very CLAIRE: Polka dots don’t have Alexa Chung about this outfit. to be cutesy. Our girl proves While on paper long-sleeved, that a few choice accessories calf-length, polka-dot co-ords can turn a twee print into an sound hard to pull off, this street uber-cool look. I’ll be taking styler rocks it. The cut-out shoes tips from her styling book and and round sunglasses add the teaming dotty co-ords with right amount of edge to make chunky heels, techno shades this all so effortlessly cool. and an ice white backpack. WE ❤ YOUR STYLE Our fashion team spy the street stylers nailing this summer’s key trends Kim Pidgeon, Claire Blackmore, fashion editor deputy fashion editor KIM: If you’ve been looking for CLAIRE: Cropped jacket, double KIM: If you’re going to rock CLAIRE: Culotte jumpsuits double denim inspiration, look denim and flares all in S/S15’s one hot hue, why not make can be a tough trend to wear no further. The frayed jean dress boldest colours – this lady’s top it magenta? This wide-leg well, but with powder blue and flares combo is this season’s of the catwalk class. I love the jumpsuit has easy breezy shoes, matching sunnies and trend heaven. The emerald clashing shades and strong lines summer style written all over an arty bag, this fashionista green boxy jacket, the snake- created by the pockets and it, while the ankle-tie heels masters it. The hot pink works print lace-up heels and the hems cutting her off at different and sunnies give an injection with her pastel accessories patent bag are what make this points on the body. -

GIRL with a CAMERA a Novel of Margaret Bourke-White

GIRL WITH A CAMERA A Novel of Margaret Bourke-White, Photographer Commented [CY1]: Add Photographer? By Carolyn Meyer Carolyn Meyer 100 Gold Avenue SW #602 Albuquerque, NM 87102 505-362-6201 [email protected] 2 GIRL WITH A CAMERA Sometime after midnight, a thump—loud and jarring. A torpedo slams into the side of our ship, flinging me out of my bunk. The ship is transporting thousands of troops and hundreds of nurses. It is December 1942, and our country is at war. I am Margaret Bourke-White, the only woman photographer covering this war. The U.S. Army Air Forces has handed me a plum assignment: photographing an Allied attack on the Germans. I wanted to fly in one of our B-17 bombers, but the top brass ordered me to travel instead in the flagship of a huge convoy, headed from England through the Straits of Gibraltar towards the coast of North Africa. It would be safer than flying, the officers argued. As it turns out, they were dead wrong. Beneath the surface of the Mediterranean, German submarines glide, silent and lethal, stalking their prey. One of their torpedoes has found its mark. I grab my camera bag and one camera, leaving everything else behind, and race to the bridge. I hear the order blare: Abandon ship! Abandon ship! There is not enough light and not enough time to take photographs. I head for Lifeboat No. 12 and board with the others assigned to it, mostly nurses. We’ve drilled for it over and over, but this is not a drill. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 12 AUGUST 1ST, 2016 August 1, 2016 Up the Ladder INCOMING LETTERS Written by Paul McGowan I am responding to the recent article on DACs and the quick brush-off of ladder DACs. (Richard Murison’s “My Kingdom for a DAC”, Richard didn’t brush off ladder DACs so much as say that they were damned hard to build properly --Ed.) There are several R2R or ladder DACs on the market and in my opinion and that of many others they are far superior to any delta-sigma DAC on the market. The best example is the Audio-GD Master 7 dac. Also, the great Audio Note DACs are ladder DACs. These DACs have a musicallity that delta- sigma DACs dream about. Delta-sigma dacs are used mostly because R2R chips are simply too difficult and expensive to make.The old R2R chips are expensive, hard to find and no longer in production. I believe Mytek is making an R2R chip and Audio Note has one in development. Did a recent comparison of my Master 7 with a friend’s DCS stack and even he thought the Master 7 was better. The DCS is 10 times the price. Yes, a ladder DAC will not do DSD, but for me that is no great loss. Alan Hendler Doesn't Like Tchaikovsky Either Three cheers for Mr. Schenbeck. He writes concisely and entertainingly and, with his adroit embedding of musical examples, uses the electronic magazine format as it should be used. I look forward to each of his contributions. Never much liked Tchaikovsky either. -

Bikini Arrests, 1940-1960

W A V E R L E Y C O U N C I L BIKINI WARS A W a v e r l e y L i b r a r y L o c a l H i s t o r y F a c t S h e e t Although two piece swimsuits of keeping the costume in have been around since position. Ancient Rome (mosaics While it is impossible to say depicted found in the Villa who was the first to wear the Romana del Casale showed risqué bathing suit to Bondi women wearing bandeau tops Beach, there has been a history and shorts to compete in of arrests of women who dared sports), the bikini as we to breach the 1935 ordinance recognise it is commonly on swimming costumes. credited to French engineer Louis Réard in 1946. According to a Sunday However, the humble bikini has Telegraph report seen its share of controversy in 1946, an unnamed woman over the last 75 years. braved Bondi promenade wearing a bikini and ‘caused a In Waverley, bathing suits near riot’. Waverley Council needed to meet stringent Lifeguard (then known as measurement requirements to Beach Inspectors) Aub Laidlaw be allowed on public beaches. told her she was indecently The Local Government attired and ordered her to the Ordinance No. 52 (1935) changing sheds at Bondi indicated that both men and Pavilion with instructions to put women’s costumes must have on some more clothes. legs at least 3" long, must Later charged with offensive completely cover the front of behaviour, this was just one of the body from the level of the many events in the armpits to the waist, and have subsequent fight against ‘public shoulder straps or other means indecency’. -

Wacoal Holdings Corp. Fundamental Company

+44 20 8123 2220 [email protected] Wacoal Holdings Corp. Fundamental Company Report Including Financial, SWOT, Competitors and Industry Analysis https://marketpublishers.com/r/W7133F8C68FBEN.html Date: September 2021 Pages: 50 Price: US$ 499.00 (Single User License) ID: W7133F8C68FBEN Abstracts Wacoal Holdings Corp. Fundamental Company Report provides a complete overview of the company’s affairs. All available data is presented in a comprehensive and easily accessed format. The report includes financial and SWOT information, industry analysis, opinions, estimates, plus annual and quarterly forecasts made by stock market experts. The report also enables direct comparison to be made between Wacoal Holdings Corp. and its competitors. This provides our Clients with a clear understanding of Wacoal Holdings Corp. position in the Clothing, Textiles and Accessories Industry. The report contains detailed information about Wacoal Holdings Corp. that gives an unrivalled in-depth knowledge about internal business-environment of the company: data about the owners, senior executives, locations, subsidiaries, markets, products, and company history. Another part of the report is a SWOT-analysis carried out for Wacoal Holdings Corp.. It involves specifying the objective of the company's business and identifies the different factors that are favorable and unfavorable to achieving that objective. SWOT-analysis helps to understand company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and possible threats against it. The Wacoal Holdings Corp. financial analysis covers the income statement and ratio trend-charts with balance sheets and cash flows presented on an annual and quarterly basis. The report outlines the main financial ratios pertaining to profitability, margin analysis, asset turnover, credit ratios, and company’s long- Wacoal Holdings Corp. -

Lookbook a CAT CALLED SAM & a DOG NAMED DUKE

AW21 A CAT CALLED SAM & A DOG NAMED DUKE click here to VIEW OUR Lookbook VIDEO thebonniemob.com AW21 AW21 S STAINABLE A CAT CALLED SAM & RECYCLE ORG NIC A DOG NAMED DUKE This is the story of a cat called Sam and a dog named Duke. Everyone said that they couldn’t be friends, because cats and dogs aren’t allowed to like each other!!! But Sam and Duke were different, they were the best of friends and loved each other very much, they liked to hang out together with their owner, a famous artist called Andy Warhol. They threw parties for all the coolest cats and dogs of New York, where they would dance the night away looking up at the city skyline, when they spotted a shooting star they’d make wishes for a world filled with art and colour and fun and kindness.......... click here click here click here to for to VIEW COLLECTION VIEW OUR INSPIRATION runthrough VIDEO Video Video CULTURE T shirt click click here CAMPBELL here for Hareem pants to order line sheets online CANDY dress THUMPER #welovebonniemob tights 2 3 thebonniemob.com AW21 LIZ A Hat G NI R C LIBERTY O ABOUT US Playsuit C LEGEND We are The bonnie mob, a multi-award winning sustainable baby and O N childrenswear brand, we are a family business, based in Brighton, on the sunny T T O Blanket South Coast of England. We are committed to doing things differently, there are no differences between what we want for our family and what we ask from our brand. -

Myth Y La Magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2015 Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America Hannah R. Widdifield University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Widdifield, Hannah R., "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hannah R. Widdifield entitled "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Lisi M. Schoenbach, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Allen R. Dunn, Urmila S. Seshagiri Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Hannah R. -

Management's Discussion and Analysis

FACTS Management’s Discussion and Analysis Wacoal Holdings Corp. and Subsidiaries Financial information contained in this section is based on the consoli- OVERVIEW OF STATUS OF BUSINESS PERFORMANCE, ETC. dated financial statements included in this integrated report, prepared in Status of Financial Position and Operation Results Status accordance with generally accepted accounting principles in the United of Financial Position States (U.S. GAAP). Total assets at the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019 (fiscal 2019) was The Wacoal Group consists of one holding company (the Company), ¥281,767 million, a decrease of ¥16,767 million compared with the end 57 consolidated subsidiaries, and eight equity-method affiliates. The of the previous fiscal year, due to a decrease in investments resulting Wacoal Group manufactures, wholesales, and—for certain products— from a decrease in market value and impairment charges on goodwill. retails women’s foundation garments and lingerie, nightwear, children’s Total liabilities at the end of fiscal 2019 was ¥60,623 million, a underwear, outerwear and sportswear, hosiery, and other textile products. decrease of ¥414 million compared with the end of the previous fiscal Other operations include restaurant businesses, cultural and service- year, due to decreases in trade payables and deferred tax liabilities, related operations, and the construction of interiors for commercial despite an increase in short-term bank loans and a recognition of premises. refund liabilities. Total Wacoal Holdings Corp. shareholders’ equity at the end of fiscal OVERVIEW 2019 was ¥216,494 million, a decrease of ¥16,218 million compared We are a leading designer, manufacturer, and marketer in Japan of with the end of the previous fiscal year, due to cash dividend payments, women’s intimate apparel, with the largest share of the Japanese market repurchase of treasury stock, and decreases in pension liability for foundation garments and lingerie. -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk