The Franciscan Conundrum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heretical Networks Between East and West: the Case of the Fraticelli

Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli NICKIPHOROS I. TSOUGARAKIS Abstract: This article explores the links between the Franciscan heresy of the Fraticelli and the Latin territories of Greece, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. It argues that the early involvement of Franciscan dissidents, like Angelo Clareno, with the lands of Latin Romania played an important role in the development of the Franciscan movement of dissent, on the one hand by allowing its enemies to associate them with the disobedient Greek Church and on the other by establishing safe havens where the dissidents were relatively safe from the persecution of the Inquisition and whence they were also able to send missionaries back to Italy to revive the movement there. In doing so, the article reviews all the known information about Fraticelli communities in Greece, and discovers two hitherto unknown references, proving that the sect continued to exist in Greece during the Ottoman period, thus outlasting the Fraticelli communities of Italy. Keywords: Fraticelli; Franciscan Spirituals; Angelo Clareno; heresy; Latin Romania; Venetian Crete. 1 Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli The flow of heretical ideas between Byzantium and the West is well-documented ever since the early Christian centuries and the Arian controversy. The renewed threat of popular heresy in the High Middle Ages may also have been influenced by the East, though it was equally fuelled by developments in western thought. The extent -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

Herman Bavinck's Theological Aesthetics: a Synchronic And

TBR 2 (2011): 43–58 Herman Bavinck’s Theological Aesthetics: A Synchronic and Diachronic Analysis Robert S. Covolo PhD candidate, Fuller Theological Seminary In 1914 Herman Bavinck wrote an article for the Almanak of the Vrije Universiteit entitled, “Of Beauty and Aesthetics,” which has recently been translated and republished for the English-speaking world in Essays on Religion, Science, and Society.1 While this is not the only place where Bavinck treats the subject of beauty, this article stands out as a unique, extended glimpse into Bavinck’s theological aesthetics.2 In it we see that Bavinck was conversant with philosophical aesthetics and aware of the tensions of doing theological aesthetics from both a small “c” catholic and a distinctly Reformed perspective. There are many ways to assess Bavinck’s reflections on aesthetics. For example, one could look at the intimations in Bavinck’s works of the aesthetics formulations of later Dutch Reformed writers such as Rookmaker, Seerveld, or Wolterstorff.3 1. Herman Bavinck, “Of Beauty and Aesthetic” in Essays on Religion, Science and Society, ed. John Bolt, trans. Harry Boonstra and Gerrit Sheeres (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 245–60. 2. See also Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, vol. 2, God and Creation, ed. John Bolt, trans. John Vriend (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2004), 252–55. 3. This in itself would prove to be a very interesting study. In one section of the essay Bavinck entertains an idea by a “Mister Berland” who maintains “the characterization of an anarchist situation in the arts.” See Bavinck, “Of Beauty and Aesthetics,” 252. -

"For Yours Is the Kingdom of God": a Historical Analysis of Liberation Theology in the Last Two Decades and Its Significance Within the Christian Tradition

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 "For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition Virginia Irby College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Irby, Virginia, ""For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 288. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/288 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “For Yours is the Kingdom of God:” A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Religious Studies from The College of William and Mary by Virginia Kathryn Irby Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ John S. Morreall, Director ________________________________________ Julie G. Galambush ________________________________________ Tracy T. Arwari Williamsburg, VA April 29, 2009 This thesis is dedicated to all those who have given and continue to give their lives to the promotion and creation of justice and peace for all people. -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine. -

To Hell and Back with David Bentley Hart

Theology in Scotland 27.1 (2020): 61–74 https://doi.org/10.15664/tis.v27i2.2140 Review essay To Hell and back with David Bentley Hart David Bentley Hart, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), pp. 222, ISBN 978- 0300246223. £20.00 Jonathan C. P. Birch Dr Jonathan Birch teaches theology at the University of Glasgow and is the Reviews Editor for Theology in Scotland. In 2019, that relative age of innocence when the United Kingdom’s primary concern was the terms of its departure from the European Union, Donald Tusk wondered ‘what that special place in Hell looks like for those who promoted Brexit without even a sketch of a plan’.1 The then President of the European Council was presumed to be speaking metaphorically, otherwise his remarks would have triggered even more righteous indignation than they did. But how should our inherited language concerning ‘Hell’ be understood? Perhaps the most fashionable and socially acceptable way to discuss any eschatological considerations in a European context is in terms of imminent environmental catastrophe: the judgement of God (or, safer still, ‘Nature’)2 against the human avarice which leads to climate change, and with a pronounced emphasis on the rapacious West. Elsewhere, talk of ‘sin’ or ‘final judgement’ offends many, especially when some of the worldviews and lifestyles that were once considered damnable are not only tolerated but celebrated in pluralistic societies. If David Bentley Hart is to be believed, however, no matter how socially relevant many in the Church may endeavour to make their public interventions, Christians largely maintain the conviction that Theology in Scotland 61 To Hell and back with David Bentley Hart when the end inevitably comes, eternal damnation awaits at least some. -

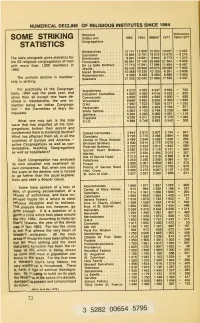

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

March 2019 RADICAL ORTHODOXYT Theology, Philosophy, Politics R P OP Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics

Volume 5, no. 1 | March 2019 RADICAL ORTHODOXYT Theology, Philosophy, Politics R P OP Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics Editorial Board Oliva Blanchette Michael Symmons Roberts Conor Cunningham Phillip Blond Charles Taylor Andrew Davison Evandro Botto Rudi A. te Velde Alessandra Gerolin David B. Burrell, C.S.C. Graham Ward Michael Hanby David Fergusson Thomas Weinandy, OFM Cap. Samuel Kimbriel Lord Maurice Glasman Slavoj Žižek John Milbank Boris Gunjević Simon Oliver David Bentley Hart Editorial Team Adrian Pabst Stanley Hauerwas Editor: Catherine Pickstock Johannes Hoff Dritëro Demjaha Aaron Riches Austen Ivereigh Tracey Rowland Fergus Kerr, OP Managing Editor & Layout: Neil Turnbull Peter J. Leithart Eric Austin Lee Joost van Loon Advisory Board James Macmillan Reviews Editor: Talal Asad Mgsr. Javier Martínez Brendan Sammon William Bain Alison Milbank John Behr Michael S Northcott John R. Betz Nicholas Rengger Radical Orthodoxy: A Journal of Theology, Philosophy and Politics (ISSN: 2050-392X) is an internationally peer-reviewed journal dedicated to the exploration of academic and policy debates that interface between theology, philosophy and the social sciences. The editorial policy of the journal is radically non-partisan and the journal welcomes submissions from scholars and intellectuals with interesting and relevant things to say about both the nature and trajectory of the times in which we live. The journal intends to publish papers on all branches of philosophy, theology aesthetics (including literary, art and music criticism) as well as pieces on ethical, political, social, economic and cultural theory. The journal will be published four times a year; each volume comprising of standard, special, review and current affairs issues. -

The Postmodern Retrieval of Neoplatonism in Jean-Luc Marion

The Postmodern Retrieval of Neoplatonism in Jean-Luc Marion and John Milbank and the Origins of Western Subjectivity in Augustine and Eriugena Hermathena, 165 (Winter, 1998), 9-70. Neoplatonism commanded important scholarly energy and poetic and literary talent in the later two-thirds of our century. Now it attracts considerable philosophical and theological interest. But this may be its misfortune. The Dominican scholar M.-D. Chenu judged the Leonine utilization of St. Thomas to have been detrimental for our understanding of his doctrine. Thomas was made an instrument of an imperialist Christianity. The use of Aquinas as a weapon against modernity required a “misérable abus.” The Holy Office made Fr. Chenu pay dearly enough for attempting accurate historical study of the Fathers and medieval doctors to make us give him heed.1 The present retrieval of our philosophical and theological past has a very different relation to institutional interests than belonged to Leonine Neothomism. The problems intellectuals now have with truthfulness come more from within themselves than from outside. There is, nonetheless, much in the character of the postmodern turn to Neoplatonism by Christian theologians to cause concern that the ecclesiastical subordination of theoria to praxis which distorted the most recent Thomism may have an analogue for Neoplatonism recovered to serve our desires.2 And if, in fact, our eye has become self-distorting, the problem in our relation to our history will be worse than anything external pressures can cause. This paper aims to begin assessing the character of this distortion in respect to a central question, our understanding of the history of western subjectivity. -

Archivio Generale St. Louis Province

INVENTORY OF THE ST. LOUIS PROVINCE COLLECTION (12) REDEMPTORIST GENERAL ARCHIVE, ROME Prepared by Patrick J. Hayes, Ph.D., Archivist Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province 7509 Shore Road Brooklyn, New York, USA 11209 718-833-1900 Email: [email protected] The Redemptorists’ Denver Province (12) has a historic beginning and storied career. Formally erected as a sister province of the Baltimore Province in 1875, it was initially known as the Vice-Province of St. Louis. It eventually divided again between regional foundations in Chicago, New Orleans, and Oakland. The Denver Province presently affiliates with the Vice- Provinces of Bangkok and Manaus and hosts the external province of Vietnam. Today, the classification system at the Archivio Generale Redentoristi (AGR), has retained the name of the original St. Louis Province in identifying the collection associated with this unit of the Redemptorist family. A good place to begin to understand the various permutations of the St. Louis Province is through the work of Father Peter Geiermann’s Annals of the St. Louis Province (1924) in three thick volumes. Unfortunately, it has never been updated. The Province awaits its own full-scale history. The St. Louis Province covered a large swath of the United States at one point—from Whittier, California to Detroit, Michigan and Seattle, Washington to New Orleans, Louisiana. Redemptorists of this province were present in cities such as Wichita and Kansas City, Fresno and Grand Rapids, San Francisco and San Antonio. Their formation houses reached into Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Schools could be found in Oakland and Detroit. Their shrines in Chicago, New Orleans, and St. -

May 26, 2000 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial. 4 From the Archives. 25 Question Corner . 11 TheCriterion Sunday & Daily Readings. 11 Criterion Vacation/Travel Supplement . 13 Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org May 26, 2000 Vol. XXXIX, No. 33 50¢ Two men to be ordained to the priesthood By Margaret Nelson His first serious study of religion was of 1979—four months into the Iran civil his sister and her husband when he was 6 Islam, when he began to teach in Saudi war. years old. Archbishop Daniel M. Buechlein will Arabia. A history professor there, “a wise “I approached the nearest Catholic At his confir- ordain two men to the priesthood for the man from Iraq” who spoke fluent English, Church—St. Joan of Arc in Indianapolis.” mation in 1979, Archdiocese of Indianapolis at 11 a.m. on talked with him He asked Father Donald Schmidlin for Borders didn’t June 3 at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in about his own instructions. Since that was before the think of the Indianapolis. faith. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults priesthood. He They are Larry Borders of St. Mag- “He knew process was so widespread, he met with had been negoti- dalen Parish in New Marion—who spent more about the priest and two other men every week ating a teaching two decades overseas teaching lan- Christianity than or so. job in Japan to guages—and Russell Zint of St. Monica I knew about The week before Christmas in 1979, begin a 15-year Parish in Indianapolis—who studied engi- my own tradi- Borders was confirmed into the Catholic contract. -

Book Viii of De Pauperie Salvatoris by Richard Fitzralph, and William Woodford's Defensorium

CHRIST'S POVERTY IN ANTIMENDICANT DEBATE: BOOK VIII OF DE PAUPERIE SALVATORIS BY RICHARD FITZRALPH, AND WILLIAM WOODFORD'S DEFENSORIUM Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Bridget Riley Submitted July 2019 ABSTRACT This thesis comprises a study of two fourteenth-century texts, written as part of the mendicant controversy, book VIII of De pauperie Salvatoris by Richard FitzRalph, Archbishop of Armagh, (c. 1300-1360) and its response, Defensorium Fratrum Mendicantium contra Ricardum Armachanum in Octavo Libello de Pauperie Christi, by the English Franciscan friar, William Woodford (c. 1330-c. 1397). It introduces each theologian, speculating why such significant fourteenth-century thinkers are not more widely known to scholars of this period. It briefly explores how contemporary understandings of the practice of mendicancy have become obscured within a historiography which seems reluctant to turn to the works of the critics of the mendicant friars for information. Based on a close-reading of each text, the thesis examines FitzRalph's declaration that Christ did not beg, and Woodford's assertion that he did, noting how each theologian uses scripture, the writings of the Church fathers, those of mendicant theologians, and mobilizes arguments from the classical philosopher, Aristotle, to construct their opposing viewpoints. Focussing especially on discussions about poverty, and about the life and activities of Christ, it suggests that information valuable to social historians is located in these texts, where each theologian constructs their own worldview, and rationalizes their position. Of particular interest is FitzRalph's radical fashioning of Christ as a labouring carpenter, and Woodford's construction of a socio-economic and an anti-semitic argument to disprove it.