Ginsberg's Quest to Resurrect Whitman's America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whitman's 1855 “Leaves of Grass” As the Emodiment of Emerson's

the Unitarian Universalist School of the Graduate Theological Union At the Beginning of a Great Career: Whitman’s 1855 “Leaves of Grass” as the Emodiment of Emerson’s “The Poet” James C. (Jay) Leach Leach wrote this paper in May 2001 for a Unitarian Universalist History class. “I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of ‘Leaves of Grass.’ I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit & wisdom that America has yet contributed.” from Emerson’s 21 July 1855 letter to Whitman “I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil.” Whitman on Emerson July 1855. Lydia Jackson (Lidian) Emerson, an ardent abolitionist who had been active in the anti- slavery movement for years, (beginning at a time when her husband was still maintaining his posi- tion of “wise passiveness,”) stepped outside of their home in Concord, Massachusetts on the route of Paul Revere’s celebrated ride, and draped the gate and fence posts in black for the July 4th holiday. It was her personal expression of somber protest against the continued presence of slavery in the United States. Her funereal bunting matched the mood in the Emerson household: Lidian was not in good health; Emerson’s brother William continued to struggle with debilitating headaches; even his friend Thoreau was ailing. Despite his earlier equivocation, by this point it had been 11 years since Ralph Waldo Emerson had relinquished his detached role as scholar-poet and actively assumed the mantle of vocal abolitionist as well. His lectures, in addition to addressing his usual philosophical and aesthetic topics, were now often about the evils of slavery. -

The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Maine History Volume 27 Number 4 Article 4 4-1-1988 The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Daniel Aaron Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Modern Literature Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Aaron, Daniel. "The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow." Maine History 27, 4 (1988): 42-67. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol27/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANIEL AARON THE LEGACY OF HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW Once upon a time (and it wasn’t so long ago), the so-called “household” or “Fire-Side” poets pretty much made up what Barrett Wendell of Harvard University called “the literature of America.” Wendell devoted almost half of his still readable survey, published in 1900, to New England writers. Some of them would shortly be demoted by a new generation of critics, but at the moment, they still constituted “American literature” in the popular mind. The “Boston constellation” — that was Henry James’s term for them — had watched the country coalesce from a shaky union of states into a transcontinental nation. They had lived through the crisis of civil war and survived, loved, and honored. Multitudes recognized their bearded benevolent faces; generations of school children memorized and recited stanzas of their iconic poems. Among these hallowed men of letters, Longfellow was the most popular, the most beloved, the most revered. -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

American Beat Yogi

Linda T. Klausner Masters Thesis: Literature, Culture, and Media Professor Eva Haettner-Aurelius 22 Apr 2011 American Beat Yogi: An Exploration of the Hindu and Indian Cultural Themes in Allen Ginsberg Klausner ii Table of Contents Preface iii A Note on the Mechanics of Writing v Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Early Life, Poetic Vision, and Critical Perspectives 10 Chapter 2: In India 21 Chapter 3: The Change 53 Chapter 4: After India 79 Conclusion 105 Sources 120 Appendix I. Selected Glossary of Hindi and Sanskrit Words 128 Appendix II. Descriptions of Prominent Hindu Deities 130 Klausner iii Preface I am grateful for the opportunity to have been able to live in Banaras for researching and writing this paper. It has provided me an invaluable look at the living India that Ginsberg writes about, and enabled me to see many facets that would otherwise have been impossible to discover. In the spirit of research and my deep passion for the subject, I braved temperatures nearing 50º Celsius. Not weather particularly conducive to thesis-writing, but what I was able to discover and experience empowers me to do it again in a heartbeat. Since the first draft, I contracted a mosquito-borne tropical illness called Dengue Fever, for which there is no vaccine. I left India for a season to recover, and returned to complete this study. The universe guided me to some amazing mentors, including Anand Prabhu Barat at the literature department of Banaras Hindu University, who specializes in the Eastern spiritual themes of the Beat Generation. She and Ginsberg had corresponded, and he sent her several works including Allen Ginsberg: Collected Works, 1947 – 1980. -

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies At

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies at 101 An unapologetic proponent of “poetry as insurgent art,” he was also a publisher and the owner of the celebrated San Francisco bookstore City Lights. By Jesse McKinley Feb. 23, 2021 Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a poet, publisher and political iconoclast who inspired and nurtured generations of San Francisco artists and writers from City Lights, his famed bookstore, died on Monday at his home in San Francisco. He was 101. The cause was interstitial lung disease, his daughter, Julie Sasser, said. The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.) While older and not a practitioner of their freewheeling personal style, Mr. Ferlinghetti befriended, published and championed many of the major Beat poets, among them Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Michael McClure, who died in May. His connection to their work was exemplified — and cemented — in 1956 with his publication of Ginsberg’s most famous poem, the ribald and revolutionary “Howl,” an act that led to Mr. Ferlinghetti’s arrest on charges of “willfully and lewdly” printing “indecent writings.” In a significant First Amendment decision, he was acquitted, and “Howl” became one of the 20th century’s best-known poems. -

Presenting Walt Whitman: "Leaves-Droppings" As Paratext

Volume 19 Number 1 ( 2001) pps. 1-17 Presenting Walt Whitman: "Leaves-Droppings" as Paratext Edward Whitley ISSN 0737-0679 (Print) ISSN 2153-3695 (Online) Copyright © 2001 Edward Whitley Recommended Citation Whitley, Edward. "Presenting Walt Whitman: "Leaves-Droppings" as Paratext." Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 19 (Summer 2001), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.13008/2153-3695.1664 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walt Whitman Quarterly Review by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESENTING WALT WHITMAN: "LEAVES-DROPPINGS" AS PARATEXT EDWARD WHITLEY IT HAS BEEN LONG RECOGNIZED that Ralph Waldo Emerson's encourag ing letter to Walt Whitman after receiving a copy of the first (1855) edition of Leaves of Grass was instrumental in securing future success for the poet. Ed Folsom and Gay Wilson Allen write, "If it hadn't been for Emerson's electrifying letter greeting Whitman at 'the beginning of a great career,' the first edition of Leaves of Grass . .. would have been a total failure; few copies were sold, and Emerson and Whitman seemed about the only people who recognized much promise in it."! But com forting as it must have been to a disheartened Whitman, Emerson's letter did more than heal a bruised ego. Whitman aggressively used the letter to promote sales of future editions of Leaves of Grass by having it quickly published (without Emerson's permission) in the New York Tribune- and by embossing the key words from Emerson's letter, "I Greet You at the / Beginning of A / Great Career / R W Emerson," on the spine of the second (1856) edition. -

The 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation Jamie L. Rehlaender Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Cultural History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Rehlaender, Jamie L., "A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Jamie L. Rehlaender Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 201: History of the US Portland State University March 19, 2015 2 A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Allen Ginsberg’s first recitation of his poem Howl , on October 13, 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, ended in tears, both from himself and from members of the audience. “The people gasped and laughed and swayed,” One Six Gallery gatherer explained, “they were psychologically had, it was an orgiastic occasion.”1 Ironically, Ginsberg, upon initially writing Howl , had not intended for it to be a publicly shared piece, due in part to its sexual explicitness and personal references. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation

DOCTORAL THESIS Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation Reynolds, Loni Sophia Award date: 2011 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation by Loni Sophia Reynolds BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing University of Roehampton 2011 Reynolds i ABSTRACT My thesis explores the role of religion and spirituality in the work of the Beat Generation, a mid-twentieth century American literary movement. I focus on four major Beat authors: William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso. Through a close reading of their work, I identify the major religious and spiritual attitudes that shape their texts. All four authors’ religious and spiritual beliefs form a challenge to the Modern Western worldview of rationality, embracing systems of belief which allow for experiences that cannot be empirically explained. -

Walt Whitman's Letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson

Walt Whitman’s Letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson Appended to the 1856 Edition of Leaves of Grass BROOKLYN, August, 1856. HERE are thirty-two Poems, which I send you, dear Friend and Master, not having found how I could satisfy myself with sending any usual acknowledgment of your letter. The first edition, on which you mailed me that till now unanswered letter, was twelve poems — I printed a thousand copies, and they readily sold; these thirty-two Poems I stereotype, to print several thousand copies of. I much enjoy making poems. Other work I have set for myself to do, to meet people and The States face to face, to confront them with an American rude tongue; but the work of my life is making poems. I keep on till I make a hundred, and then several hundred — perhaps a thousand. The way is clear to me. A few years, and the average annual call for my Poems is ten or twenty thousand copies — more, quite likely. Why should I hurry or compromise? In poems or in speeches I say the word or two that has got to be said, adhere to the body, step with the countless common footsteps, and remind every man and woman of something. Master, I am a man who has perfect faith. Master, we have not come through centuries, caste, heroisms, fables, to halt in this land today. Or I think it is to collect a ten-fold impetus that any halt is made. As nature, inexorable, onward, resistless, impassive amid the threats and screams of disputants, so America. -

What Are You If Not Beat? – an Individual, Nothing

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “What are you if not beat? – An individual, nothing. They say to be beat is to be nothing.”1 Individual and Collective Identity in the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Sarah Posman fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Sarah Devos May 2014 1 From “Variations on a Generation” by Gregory Corso 0 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Posman for keeping me motivated and for providing sources, instructive feedback and commentaries. In addition, I would like to thank my readers Lore, Mathieu and my dad for their helpful additions and my library companions and friends for their driving force. Lastly, I thank my two loving brothers and especially my dad for supporting me financially and emotionally these last four years. 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1. Ginsberg, Beat Generation and Community. ............................................................ 7 Internal Friction and Self-Promotion ...................................................................................... 7 Beat ......................................................................................................................................... 8 ‘Generation’ & Collective Identity ......................................................................................... 9 Ambivalence in Group Formation -

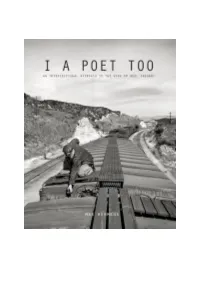

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis.