The Impact of National Service on Critical Social Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Kennedy, Richard M

1 1960 Presidential election candidates John F. Kennedy, Richard M. Nixon, Democrat Republican 2 Campaign propaganda and the candidate’s wives Jacqueline Patricia 3 Kennedy Nixon John F. Kennedy Born on May 29, 1917 in Brookline, Massachusetts World War II hero when he saved his crew after his PT boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer in 1942 His father convinced him to enter politics; he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1946 and the Senate in 1952 Lost close bid for 1956 Democratic nomination for vice-president Wrote Pulitzer Prize winning novel “Profiles In Courage” in 1956 JFK was the second Catholic to run for President. Al Smith ran as the Democrat candidate in 1928 and lost. 4 Richard M. Nixon Born on January 11, 1913 in Yorba Linda, California Elected to the House of Representatives in 1946 Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1950 Known as a staunch anti-communist; investigated State Department official Alger Hiss, who was convicted of perjury Nixon Nominated for vice president in 1952 accepted by Dwight Eisenhower; won second the term as vice president in 1956 nomination for Won acclaim for “kitchen debate” president in with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev 1960 in 1959 5 This was the first televised debate between presidential candidates. Nixon was unshaven and sweating, while Kennedy was tan and full of energy. JFK was considered by many to have won the debate which may have had contributed to his narrow electoral victory. Senator These chairs were used Vice President John F. Kennedy by nominees John F. -

142000 IOP.Indd

NOVEMBER 2004 New Poll Released Director’s Search Begins Justice Scalia Visits the Forum Nader Visits the Forum Skirting Tradition Released Campaign 2004 Comes to Harvard Hundreds of students attend a Debate Watch in the JFK Jr. Forum Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University P HIL S HARP , I NTERIM D IRECTOR I was thrilled to return to the Institute of Politics for the fall 2004 semes- ter while a new long-term director is recruited. As a former IOP Director (1995-1998), I jumped at the chance to return to such a special place at an important time. This summer, IOP Director Dan Glickman, Harvard students, and IOP staff went into high gear to mobilize, inspire, and engage young people in politics and the electoral process. • We hosted events for political powerbrokers during the Democratic and Republican National Conventions. • We are working to ensure all Harvard voices are heard at the polls through our dynamic and effective H-VOTE campus vote pro- gram, as well as coordinating the voter education and mobilization activities of nearly 20 other schools across America, part of our National Campaign for Political and Civic Engagement. • Our Resident Fellows this semester are an impressive group. They bring experiences from media, to managing campaigns, to the Middle East. See inside for more information on our exciting fellows. • A survey we conducted with The Chronicle of Higher Education found that most of America’s college campuses are politically active, but 33% of schools fail to meet federal requirements facili- tating voter registration opportunities for students. -

September 11 & 12 . 2008

n e w y o r k c i t y s e p t e m b e r 11 & 12 . 2008 ServiceNation is a campaign for a new America; an America where citizens come together and take responsibility for the nation’s future. ServiceNation unites leaders from every sector of American society with hundreds of thousands of citizens in a national effort to call on the next President and Congress, leaders from all sectors, and our fellow Americans to create a new era of service and civic engagement in America, an era in which all Americans work together to try and solve our greatest and most persistent societal challenges. The ServiceNation Summit brings together 600 leaders of all ages and from every sector of American life—from universities and foundations, to businesses and government—to celebrate the power and potential of service, and to lay out a bold agenda for addressing society’s challenges through expanded opportunities for community and national service. 11:00-2:00 pm 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE Organized by myGoodDeed l o c a t i o n PS 124, 40 Division Street SEPTEMBER 11.2008 4:00-6:00 pm REGIstRATION l o c a t i o n Columbia University 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE 6:00-7:00 pm OUR ROLE, OUR VOICE, OUR SERVICE PRESIDENTIAL FORUM& 101 Young Leaders Building a Nation of Service l o c a t i o n Columbia University Usher Raymond, IV • RECORDING ARTIST, suMMIT YOUTH CHAIR 7:00-8:00 pm PRESIDEntIAL FORUM ON SERVICE Opening Program l o c a t i o n Columbia University Bill Novelli • CEO, AARP Laysha Ward • PRESIDENT, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND TARGET FOUNDATION Lee Bollinger • PRESIDENT, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Governor David A. -

Program Year Americorps Program Director Handbook

2017- Program Year 2018 AmeriCorps Program Director Handbook Program Director Handbook 2017-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1 CORPORATION FOR NATIONAL AND COMMUNITY SERVICE 1 AMERICORPS 1 AMERICORPS STATE AND NATIONAL DIRECT 1 AMERICORPS VISTA (VOLUNTEERS IN SERVICE TO AMERICA) 2 AMERICORPS NCCC (NATIONAL CIVILIAN COMMUNITY CORPS) 2 THE MASSACHUSETTS SERVICE ALLIANCE 2 NATIONAL SERVICE 2 AMERICORPS IN MASSACHUSETTS 3 MSA STAFF 3 AMERICORPS RULES AND REGULATIONS 4 OTHER REQUIREMENTS 4 AMERICORPS PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES 4 AMERICORPS ELIGIBILITY 5 CITIZENSHIP OR ALLOWABLE LEGAL STATUS REQUIREMENT 6 PRIMARY DOCUMENTATION OF STATUS AS A UNITED STATES’ CITIZEN OR NATIONAL 6 PRIMARY DOCUMENTATION OF STATUS AS A UNITED STATES’ LAWFUL PERMANENT RESIDENT ALIEN 6 EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT 7 HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA/GED 7 GED AGREEMENT LETTER 7 CRIMINAL HISTORY CHECK REQUIREMENTS 7 NATIONAL SEX OFFENDER PUBLIC WEBSITE (NSOPW) 9 STATEWIDE CRIMINAL REGISTRY 9 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION (FBI) 9 ACCOMPANIMENT 10 CRIMINAL HISTORY CHECK POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 11 CRIMINAL HISTORY CHECK RESOURCES 11 ALTERNATIVE SEARCH PROCEDURES 11 USE OF AMERICORPS NAME AND LOGO 12 IDENTIFICATION AS AN AMERICORPS PROGRAM OR MEMBER 13 AMERICORPS RECRUITMENT, SELECTION, AND ORIENTATION 13 AMERICORPS MEMBER POSITION DESCRIPTION 13 MY AMERICORPS PORTAL 15 AMERICORPS MEMBER ENROLLMENT 15 SERVICE LOCATION DESIGNATION 15 MEMBER FORMS 16 ENROLLMENT POLICY 16 REFILL POLICY 16 AMERICORPS MEMBER SUPERVISION 16 PERFORMANCE REVIEWS 17 SERVICE OBJECTIVES 17 AMERICORPS MEMBER -

Americorps*VISTA

National Service: A Bridge to Employment for Individuals with Disabilities YOUR WORLD. YOUR CHANCE TO MAKE IT BETTER. www.nationalservice.gov The National Service Family There are three programs under the Corporation for National and Community Service: • Senior Corps: 500,000 Americans 55+ • AmeriCorps: 75,000 members • Learn and Serve America: 1.4 million students in service-learning AmeriCorps Getting Things Done for America AmeriCorps Rooted in America’s Tradition of Service 1933: Civilian Conservation Corps 1961: Peace Corps 1964: VISTA 1994: AmeriCorps AmeriCorps Today Three Programs AmeriCorps AmeriCorps AmeriCorps State and VISTA NCCC National AmeriCorps Today Meeting critical needs across America AmeriCorps members: • Teach and tutor students • Mentor at-risk youth • Build homes • Fight poverty • Conserve the environment • Provide health services • Respond to disasters • Recruit and manage volunteers • Much, much, more… AmeriCorps*State and National • Largest branch of AmeriCorps • About 75,000 positions each year • Members serve with more than 2,900 organizations • Positions in education, environment, health, housing, disaster response, and more • Organizations with members include Habitat for Humanity, Teach for America, City Year, American Red Cross, Boys and Girls Clubs, and thousands of other nonprofits • Full-time and part-time positions AmeriCorps*VISTA • AmeriCorps’ poverty-fighting arm • Created in 1964 as part of War on Poverty • 6,500 positions each year • VISTAs collaborate with low-income individuals and communities -

13 Days When the World Almost Ended Sunday Sept 8 6:30 Pm OMNI Center

OMNI 350 Quick Links... Citizen's Climate Become a Member Lobby Information Events Calendar Saturday Sept 7 OMNI Newsletters 11:00 am at OMNI Center Potuck lunch, connect critical environmental issues in our area, and link in to the most effective national energy policy campaign going... Citizens' Climate Lobby. You can help move the CCL energy agenda DICK BENNETT forward. Come find out how. BLOG Dick's Blog Here Citizen's Climate Lobby DICK BENNETT CURRENT NEWSLETTERS Terra Studios Syria Fall Music Festival Drones Sunday Sept 8, noon-5:00 pm Newsletter Archives Here Terra's beautiful grounds will be scattered with song circles. Ellis Ralph and Judi Neal will host OMNI's Song Circle, and Stay Involved sing songs about peace, justice and the earth. Get the full flavor, on a beautiful Join OMNI Sunday afternoon. Directions and information: Terra Studios Learn More website Come Together Events & Action Video Underground September Programs 13 Days When the world almost ended Sunday Sept 8 6:30 pm OMNI Center Thirteen Days is a 2000 docudrama about the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, seen from the perspective of US political leadership. Kevin Costner stars, with Bruce Greenwood featured as John F. Kennedy A Day for Heroes Celebrating heroes who keep our community strong Wednesday September 11 4:00-7:00 pm at Tri Cycle Farm Watermelon break too AmeriCorps VISTA helps OMNI Center and many other nonprofits by providing funding for enthusiastic young staffers who make our work effective. This service event celebrates our VISTA members by letting them do what they do well.. -

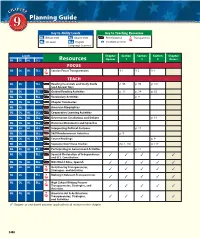

Planning Guide

Planning Guide Key to Ability Levels Key to Teaching Resources BL Below level AL Above level Print Material Transparency OL On level ELL English CD-ROM or DVD Language Learners Levels Chapter Section Section Section Chapter BL OL AL ELL Resources Opener 1 2 3 Assess FOCUS BL OL AL ELL Section Focus Transparencies 9-1 9-2 9-3 TEACH BL OL ELL Reading Essentials and Study Guide p. 95 p. 98 p. 102 (and Answer Key) BL OL ELL Guided Reading Activities p. 33 p. 34 p. 35 BL OL ELL Vocabulary Activities p. 9 BL OL AL ELL Chapter Summaries BL OL American Biographies BL OL AL ELL Cooperative Learning Activities OL AL ELL Government Simulations and Debate p. 15 BL OL AL ELL Historical Documents and Speeches BL OL AL ELL Interpreting Political Cartoons p. 17 BL OL ELL Skill Reinforcement Activities p. 9 BL OL AL ELL Source Readings p. 9 BL OL Supreme Court Case Studies pp. 1, 161 p. 117 BL OL AL ELL Participating in Government Activities p. 17 BL OL ELL Spanish Declaration of Independence ✓✓✓✓✓ and U.S. Constitution BL OL AL ELL NGS World Atlas, Spanish ✓✓✓✓✓ BL OL AL ELL Unit Overlay Transparencies, ✓✓✓✓✓ Strategies, and Activities BL OL ELL Making It Relevant Transparencies ✓✓✓✓✓ BL OL AL ELL High School Writing Process Transparencies, Strategies, and ✓✓✓✓✓ Activities BL OL AL American Art & Architecture Transparencies, Strategies, ✓✓✓✓✓ and Activities ✓ Chapter- or unit-based activities applicable to all sections in this chapter 244A 244 A_D_C09_890908.indd 244A 3/16/09 3:38:47 PM Planning Guide • Interactive Lesson Planner • Differentiated Lesson -

2017 Best Practice Sharing by Officer Role Taken Directly from the FY2017 Class Activity Report: Fellow Officers Share Their Thoughts

2017 Best Practice Sharing by Officer Role Taken directly from the FY2017 Class Activity Report: Fellow officers share their thoughts CAR – Best Practices Report – FY2017 Class Presidents Class of 1946 We are looking for other Class activities. Class of 1954 1. Under chairmanship of Steven Mullins, we formed a three man committee to reinstate the Class of 1954 Award to honor classmates who might have been overlooked under the previous program. (More than 60 Awards were presented under that program). The committee met once in person and many times over the phone and by email. We have identified up to a half dozen possible deserving candidates. One award was presented at the annual Class holiday luncheon in New York in December 2016 to Wayne Weil. We anticipate the presentation of at least two awards during 2017. 2. We have created an internship endowment chaired by Don Berlin currently valued at over $165,000 to continue annual funding of student internships into the future with a goal of at least $300,000 by our 65th Reunion. 3. We have created a Widows Program under the guidance Sue Bastian (widow of Bryce Bastian D'54) to initiate and sustain communications with class widows and to encourage participation in class activities. Class of 1955 • We conducted successfully a class survey to assess “connected” to the class/college. Conclusion: Most feel connected especially through the NL, DAM, and DAM class notes. Also noted instances of connection reduced by health and mobility concerns due to age restricting travel Class of 1957 We have developed several funds over the years, including a Travel Fund at the HOP, an Erich Kunzel Fund with the Music Department, and our legacy fund, the Class of 1957 Fund for Great Issues Innovations at the Dickey Center. -

Overview of National Service & Americorps

Overview of National Service & AmeriCorps Agenda • National Service 101 • National Service Programs • Structure of National Service • AmeriCorps Focus Areas • AmeriCorps Guiding Principles • AmeriCorps Terminology • AmeriCorps Prohibited Activities • AmeriCorps Resources What is National Service? The Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) strengthens our country by empowering AmeriCorps members and Senior Corps volunteers to solve local problems nationwide. In coordination with state and local entities, national service responds to the most pressing issues facing our nation. AmeriCorps members and Senior Corps volunteers prepare for tomorrow’s jobs, reduce crime, connect returning veterans to jobs, fight the opioid epidemic, support seniors to live independently, make college more accessible and affordable, and help Americans rebuild their lives following disasters. 1933: New Deal - Civilian National Conservation Corps 1961: Peace Corps Service 1964: War on Poverty – VISTA created History 1992: AmeriCorps NCCC 1993: National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993 created The Corporation for National and Community Service & AmeriCorps 2009: Serve America Act Edward M. Kennedy Serve • Landmark legislation to expand service America Act • Increases the amount of the education award – matches the amount of the Pell Grant of 2009 • Ed Award Transfer – 55+ may transfer education award to child, step-child, grandchild, step-grandchild, or foster child (AC*State/National only) • Priority focus on education, health, environment, -

Franklin Project's Plan of Action

Generi Corp Inc Management Report Table of Contents A Declaration of Service 1 Executive Summary 5 A Plan of Action: A 21st Century National Service System 12 Core Elements of a 21st Century National Service System 12 Pathways to Engage More Americans in National Service 22 A Talent Pipeline through National Service 25 The Case for National Service 28 National Service to Address National Challenges 33 Conclusion 38 Acknowledgments 38 Endnotes 39 A Declaration of Service We, the undersigned, endorse the Franklin Project's Plan of Action to establish a 21st Century National Service System in America that inspires and engages at least one million young adults annually from all socio- economic backgrounds in a demanding year of full-time national service as a civic rite of passage to unleash the energy and idealism of each generation to address our nation’s challenges. General Stanley McChrystal Michael Brown Leadership Council Chair, The Franklin Project; U.S. Co-Founder and CEO, City Year Army General (Retired); Former Commander, International Security Assistance Force & U.S. Forces Afghanistan Anna Burger Former Secretary-Treasurer, SEIU; Former Chair, Change to Win Madeleine Albright Chair, Albright Stonebridge Group; Former U.S. Secretary of State & U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Barbara Bush Co-Founder and CEO, Global Health Corps Don Baer Worldwide Chair and CEO, Burson-Marsteller; Former Jean Case White House Director of Strategic Planning and CEO, The Case Foundation; Former Chair, President's Communications Council on Service and Civic Participation Melody Barnes Ray Chambers Chair, Aspen Forum for Community Solutions and UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Financing of Opportunity Youth Incentive Fund; Vice Provost for the Health Related Millennium Development Goals & for Global Student Leadership Initiatives, New York Malaria; Co-Founder, America's Promise Alliance; Chair, University; Former Director, White House Domestic The MCJ Amelior Foundation Policy Council AnnMaura Connolly Samuel R. -

Moneyball for Government Principles Moneyball for Government All-Stars

Two-hundred fifty-four local, state, federal, nonprofit and academic leaders from all across the political spectrum and throughout the country support the following Moneyball for Government principles. Moneyball for Government Principles Government at all levels should help improve outcomes for young people, families, and communities by: 1) Building evidence about the practices, policies, and programs that will achieve the most effective and efficient results so that policymakers can make better decisions; 2) Investing limited taxpayer dollars in practices, policies, and programs that use data, evidence, and evaluation to demonstrate how they work; and 3) Directing funds away from practices, policies, and programs that consistently fail to achieve desired outcomes. Moneyball for Government All-Stars You can view the full list of Moneyball for Government All-Stars goo.gl/1rBMWW. Founding All-Stars • Melody Barnes (Former Director, White House Domestic Policy Council, President Barack Obama) • Michael Bloomberg (Former Mayor, New York City) • John Bridgeland (Former Director, White House Domestic Policy Council, President George W. Bush) • Jim Nussle (Former Director, White House Office of Management and Budget, President George W. Bush) • Peter Orszag (Former Director, White House Office of Management and Budget, President Barack Obama) Federal All-Stars U.S. Senate: U.S. Senator Michael Bennet (D-CO); U.S. Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT); U.S. Senator Robert Portman (R-OH); U.S. Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH); U.S. Senator Mark Warner (D-VA); U.S. Senator Todd Young (R-IN); Former U.S. Senator Kelly Ayotte (R-NH); Former U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu (D-LA) U.S. -

Staff Report

STAFF REPORT Report To: Board of Supervisors Meeting Date: November 2, 2017 Staff Contact: Jennifer Budge, CPRP, Parks and Recreation Director Agenda Title: For Possible Action: To approve the lease of 1,600 square feet of building space located at 864 Evalyn Drive to Truckee Meadows Parks Foundation, a non-profit Nevada corporation for public benefit. (Jennifer Budge, [email protected]) Staff Summary: Carson City, through its Parks and Recreation Department, and Truckee Meadows Parks Foundation (TMPF) currently have a cooperative agreement authorized by the City Manager, for three Americorps VISTA (Volunteers In Service To America) volunteers. TMPF has requested a two year lease for 1,600 square feet of building space above the concession stand at 864 Evalyn Drive within Governor's Field, to further support the Carson City Americorps VISTA program. Agenda Action: Formal Action/Motion Time Requested: 5 minutes Proposed Motion I move to approve the lease of 1,600 square feet of building space located at 864 Evalyn Drive to Truckee Meadows Parks Foundation, a non-profit Nevada corporation for public benefit. Board’s Strategic Goal Quality of Life Previous Action None Background/Issues & Analysis Nevada Revised Statutes (NRS) 244.284 & 244.2835 empower the Board of Supervisors to lease any real property owned by Carson City, to a corporation for public benefit, without offering the property to the public if the property is used for charitable or civil purposes. The property located at 864 Evalyn Drive would be leased for the purpose of housing three Americorps VISTA volunteers. The three volunteers are brought to us through a cooperative partnership with TMPF.