Illustrations 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Greco, a Mediator of Modern Painting

El Greco, a mediator of modern painting Estelle Alma Maré Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria E-mail: [email protected] Without clear articulation of their insights, except in painted copies of and citations from his works, various modern artist seem to have recognised that formally El Greco’s late paintings are mental con- structs, representing only a schematic version of reality. El Greco changed the communicative function of painting from commenting on reality to constituting a reality. It is proposed that modern artists in a quest for a new approach to painting found El Greco’s unprecedented manner of figural expression, extreme degree of anti-naturalism and compositional abstraction a source of inspiration. For various painters that may have been a starting point in finding a new paradigm for art that was at a loose end after the influence of disciples of the French Academy terminated. Key words: El Greco, copying and emulation, Diego Vélazquez, Francis Bacon, Gustave Courbet, Éduard Manet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, J.F. Willumsen, Oscar Kokoschka, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock El Greco, ’n medieerder van moderne skilderkuns Sonder dat hulle hul insigte duidelik geartikuleer het, behalwe in geskilderde kopieë van en aanhalings uit sy werke, het verskeie moderne kunstenaars blykbaar tot die insig geraak dat El Greco se latere skilderye denkkonstrukte is wat ’n geskematiseerde weergawe van die werklikheid verteenwoordig. Daar word betoog dat moderne kunstenaars op soek na ’n nuwe benadering tot die skilderkuns in El Greco se buitengewone wyse van figuurvoorstelling, anti-naturalisme en komposisionele abstraksie ’n bron van inspirasie gevind het. Vir verskeie kunstenaars was dit waarskynlik ’n aanknopingspunt vir die verwesenliking van ‘n nuwe paradigma vir kuns wat koers verloor het nadat die invloed van die dissipels van die Franse Akademie geëindig het. -

ΚΝΙΞQUΑΊLΚΊΓΚΙΞ§ ΚΝ ΊΓΗΙΞ WORIΚ of IΞJL GRIΞCO and ΊΓΗΙΞΚR ΚΝΊΓΙΞRΙΡRΙΞΊΓΑΊΓΚΟΝ 175

ΚΝΙΞQUΑΊLΚΊΓΚΙΞ§ ΚΝ ΊΓΗΙΞ WORIΚ Of IΞJL GRIΞCO AND ΊΓΗΙΞΚR ΚΝΊΓΙΞRΙΡRΙΞΊΓΑΊΓΚΟΝ 175 by Nicos Hadjinicolaou In memoryof Stella Panagopoulos, whose presence at the lecture gave me great pleasure The organization of a series of lectures in honour of a distinguished l art critic could bring the invited art historians in the delicate or uncomfortable position of defining the limits proper to art criticism and art history, thus reviving a rather sterile paragon of the 20th century. If, in the debate about the primacy of sculpture or of painting, Vasari (out of conviction it seems and not for reasons of tactics) declared that the controversy was futile because both arts were equally based οη "d isegno", Ι am afraid that tod ay a similar proposition to remove the object of dissent between art criticism and art history by claiming tha.t both were equally based οη "artistic theory" would, unfortunately, be rejected as being tόta11y out of place. Reconciliation being, at least for the moment, impossible, an art historian might be allowed to stress what in his eyes is one of the advantages of art criticism over art history: that it takes a stand, that it takes risks, that it measures the relevance of a work for the present and for the immediate future. It goes without saying that an art critic also jud ges a contemporary work under the burden of his or her knowledge of the art of the past and of the literature written ab out it. Υ et, this does not change the fundamental fact that the appreciation of the work and the value judgements about its assumed "quality" or "validity as a statement" are elements insid e a perspective looking towards the future and not towards the past. -

Incisioni, Richiestissime Da Un Mercato Molto Fiorente, Giunge Ora Una Rassegna Di Rilevante Interesse, Che Si Apre Oggi Alle 17 Nei Saloni Della Biblioteca Palatina

Parmigianino e l’incisione <Padre dell'acquaforte italiana> l'ha definito Mary Pittaluga. E Giovanni Copertini ha specificato <Sebbene non si possa più considerare come l'inventore della tecnica dell'acquaforte, pure è da esserne stimato il creatore spirituale ché, con le sue stampe, ha insegnato agli artisti a trasfondere luce d'idealità in poche linee e in un tenue motivo di segni incrociati>. E' questo il lato meno noto del Parmigianino: incantevole pittore, straordinario disegnatore e anche abilissimo incisore; una caratteristica, quella di grafico, che nella grandiosa mostra allestita per celebrare il quinto centenario della nascita dell'artista passa un po' inosservata di fronte alla parata affascinante dei dipinti e dei disegni. Ad illuminare questo aspetto non secondario dell'attività del Parmigianino sia come autore diretto sia soprattutto come fornitore di disegni da trasformare in incisioni, richiestissime da un mercato molto fiorente, giunge ora una rassegna di rilevante interesse, che si apre oggi alle 17 nei saloni della Biblioteca Palatina (fino al 27 settembre) e che ha come titolo <Parmigianino tradotto. La fortuna di Francesco Mazzola nelle stampe di riproduzione tra il Cinquecento e l'Ottocento>. La correda un catalogo, pubblicato dalla Silvana Editoriale, comprendente la presentazione del direttore della Biblioteca Leonardo Farinelli, un approfondito saggio critico di Massimo Mussini e un'introduzione alle schede di Grazia Maria de Rubeis, responsabile del gabinetto delle stampe; il volume documenta tutte le incisioni <parmigianinesche> posseduta dalla Palatina, comprese quelle non esposte, cosicché assume un notevole valore scientifico in un settore ancora scarsamente esplorato con sistematicità. E' a Roma, dove si trasferisce nel 1524, che Francesco Mazzola entra nell'ambiente degli incisori fornendo disegni a Ugo da Carpi, considerato il padre della silografia, e a Jacopo Caraglio, incisore a bulino allievo di Marco Antonio Raimondi. -

The Grotesque in El Greco

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME © Författare: Lena Beckman Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Höstterminen 2019 Handledare: Johan Eriksson ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala Universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Lena Beckman Titel och Undertitel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Engelsk titel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Handledare Johan Eriksson Ventileringstermin: Hösttermin (år) Vårtermin (år) Sommartermin (år) 2019 2019 Content: This study attempts to investigate the grotesque in four paintings of the artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos or El Greco as he is most commonly called. The concept of the grotesque originated from the finding of Domus Aurea in the 1480s. These grottoes had once been part of Nero’s palace, and the images and paintings that were found on its walls were to result in a break with the formal and naturalistic ideals of the Quattrocento and the mid-renaissance. By the end of the Cinquecento, artists were working in the mannerist style that had developed from these new ideas of innovativeness, where excess and artificiality were praised, and artists like El Greco worked from the standpoint of creating art that were more perfect than perfect. The grotesque became an end to reach this goal. While Mannerism is a style, the grotesque is rather an effect of the ‘fantastic’.By searching for common denominators from earlier and contemporary studies of the grotesque, and by investigating the grotesque origin and its development through history, I have summarized the grotesque concept into three categories: between form, beyond language and beside the sublime. -

Xavier F. Salomon Appointed Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator of the Frick Collection

XAVIER F. SALOMON APPOINTED PETER JAY SHARP CHIEF CURATOR OF THE FRICK COLLECTION Xavier F. Salomon has been appointed to the position of Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator of The Frick Collection, taking up the post in January of 2014. Dr. Salomon―who has organized exhibitions and published most particularly in the areas of Italian and Spanish art of the sixteenth through eighteenth century―comes to The Frick Collection from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he is a curator of in the Department of European Paintings. Previously, he was the Arturo and Holly Melosi Chief Curator of Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. Salomon’s two overall fields of expertise are the painter Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) and the collecting and patronage of cardinals in Rome during the early seventeenth century. Born in Rome, and raised in Italy and the United Kingdom, Salomon received his Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. A widely published author, essayist, and reviewer, Salomon sits on the Consultative Committee of The Burlington Magazine and is a member of the International Scientific Committee of Storia dell’Arte. Comments Frick Director Ian Wardropper, “We are thrilled to welcome Salomon to the post of Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator. He is a remarkable scholar of great breadth and vitality, evidenced by his résumé, on which you will find names as far ranging as Veronese, Titian, Carracci, Guido Reni, Van Dyck, Claude Lorrain, Poussin, Tiepolo, Lucian Freud, Cy Twombly, and David Hockney. At the same time, he brings to us significant depth in the schools of painting at the core of our Old Master holdings, and he will complement superbly the esteemed members of our curatorial team. -

Music As an Angelic Message in El Greco's Oeuvre

Music as an angelic message in El Greco’s oeuvre Estelle Alma Maré Department of Architecture, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria E-mail: [email protected] Angels are assumed to represent messengers from God and in Christian art they are traditionally de- picted as winged human beings. In the visual arts all figures are mute; therefore angel music as the divine message relayed to the viewer needs to be interpreted as a form of visual gestural rhetoric with an imaginary auditive reference. In order to treat this theme, the article is introduced by a general discussion of the representation of angels in El Greco=s oeuvre, followed by a brief orientation to the theme of angel musicians in Medieval and Renaissance art. An analysis of El Greco=s paintings that include heavenly musicians reveal that the interaction between heaven and earth becomes continuous, eliminating the contrast between these zones that was postulated by Aristotle. Even though only a lim- ited number of El Greco=s paintings include angel musicians, their active presence in some of his most imaginative compositions illustrate the way in which he evolved an unique iconographical convention related to the theme of these consorts, and his innovative expansion of the meaning of the being and missions of angels. Keywords: El Greco, angel consort, harmony of the spheres, musical instruments Musiek as =n engel-boodskap in El Greco se oeuvre Dit word veronderstel dat engele boodskappers van God is en in Christelike kuns word hulle tradi- sioneel as gevlerkte mensfigure voorgestel. In die visuele kunste is alle figure stom; dus moet en- gel-musiek as die goddelike boodskap wat aan die aanskouer oorgedra word, as =n vorm van visuele gebare-retorika met =n denkbeeldige ouditiewe verwysing geïnterpreteer word. -

Cna85b2317313.Pdf

THE PAINTERS OF THE SCHOOL OF FERRARA BY EDMUND G. .GARDNER, M.A. AUTHOR OF "DUKES AND POETS IN FERRARA" "SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA" ETC LONDON : DUCKWORTH AND CO. NEW YORK : CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO FRANK ROOKE LEY PREFACE Itf the following pages I have attempted to give a brief account of the famous school of painting that originated in Ferrara about the middle of the fifteenth century, and thence not only extended its influence to the other cities that owned the sway of the House of Este, but spread over all Emilia and Romagna, produced Correggio in Parma, and even shared in the making of Raphael at Urbino. Correggio himself is not included : he is too great a figure in Italian art to be treated as merely the member of a local school ; and he has already been the subject of a separate monograph in this series. The classical volumes of Girolamo Baruffaldi are still indispensable to the student of the artistic history of Ferrara. It was, however, Morelli who first revealed the importance and significance of the Perrarese school in the evolution of Italian art ; and, although a few of his conclusions and conjectures have to be abandoned or modified in the light of later researches and dis- coveries, his work must ever remain our starting-point. vii viii PREFACE The indefatigable researches of Signor Adolfo Venturi have covered almost every phase of the subject, and it would be impossible for any writer now treating of Perrarese painting to overstate the debt that he must inevitably owe to him. -

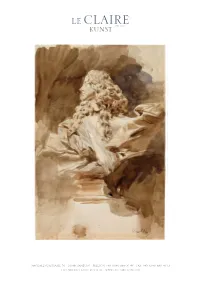

40 880 46 12 [email protected] ∙ Le Claire Kunst Seit 1982

LE CLAIRE KUNST SEIT 1982 MAGDALENENSTRASSE 50 ∙ 20148 HAMBURG ∙ TELEFON +49 (0)40 881 06 46 ∙ FAX +49 (0)40 880 46 12 [email protected] ∙ WWW.LECLAIRE-KUNST.DE LE CLAIRE KUNST SEIT 1982 GIOVANNI BOLDINI 1842 Ferrara - Paris 1931 Bust of Francesco I d’Este, after Gianlorenzo Bernini Brown and blue wash on paper; c.1890-1900. Signed lower right: Boldini 455 x 304 mm PROVENANCE: Private collection, Italy [until ca. 1985] – Thence by descent Giovanni Boldini was born in Ferrara, and in 1862 went to Florence for six years to study and practise painting. He attended classes at the Academy of Fine Arts only infrequently but nevertheless came into contact there with a group of young Florentine painters known as the ‘Macchiaioli’1. Their influence is seen in Boldini’s landscapes which show his spontaneous response to nature, although it is for his portraits that he became best known. Moving to London, he attained considerable success as a portraitist. From 1872 he lived in Paris, where in the late 19th century he became the city’s most fashionable portrait painter, with a dashing style of painting which shows some Macchiaioli influence and a brio reminiscent of the work of younger artists. Boldini held the work of the great sculptor and architect Bernini (1598-1680) in high regard. His admiration for Bernini almost certainly sprang from a spiritual rapprochement spontaneously triggered by a gift he received from the Uffizi in 1892 at the pinnacle of his international success. The museum had requested a self-portrait from him and in exchange he was offered a cast of Bernini’s portrait bust of Leopold de’ Medici. -

Che Si Conoscono Al Suo Già Detto Segno Vasari's Connoisseurship In

Che si conoscono al suo già detto segno Vasari’s connoisseurship in the field of engravings Stefano Pierguidi The esteem in which Giorgio Vasari held prints and engravers has been hotly debated in recent criticism. In 1990, Evelina Borea suggested that the author of the Lives was basically interested in prints only with regard to the authors of the inventions and not to their material execution,1 and this theory has been embraced both by David Landau2 and Robert Getscher.3 More recently, Sharon Gregory has attempted to tone down this highly critical stance, arguing that in the life of Marcantonio Raimondi 'and other engravers of prints' inserted ex novo into the edition of 1568, which offers a genuine history of the art from Maso Finiguerra to Maarten van Heemskerck, Vasari focused on the artist who made the engravings and not on the inventor of those prints, acknowledging the status of the various Agostino Veneziano, Jacopo Caraglio and Enea Vico (among many others) as individual artists with a specific and recognizable style.4 In at least one case, that of the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence engraved by Raimondi after a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, Vasari goes so far as to heap greater praise on the engraver, clearly distinguishing the technical skills of the former from those of the inventor: [...] So when Marcantonio, having heard the whole story, finished the plate he went before Baccio could find out about it to the Pope, who took infinite 1 Evelina Borea, 'Vasari e le stampe', Prospettiva, 57–60, 1990, 35. 2 David Landau, 'Artistic Experiment and the Collector’s Print – Italy', in David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print 1470 - 1550, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994, 284. -

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 the J

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 1 6 1. Dosso Dossi (Giovanni di Niccolò de Lutero) 2. Simon Bening Italian (Ferrarese), about 1490 - 1542 Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 NUDE NUDE A Myth of Pan, 1524 Flagellation of Christ, About 1525-30 Oil on canvas from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg Unframed: 163.8 × 145.4 cm (64 1/2 × 57 1/4 in.) Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) 83.PA.15 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 154v (83.ML.115.154v) 6 5 3. Simon Bening 4. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola) Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 Italian, 1503 - 1540 NUDE Border with Job Mocked by His Wife and Tormented by Reclining Male Figure, About 1526-27 NUDE Two Devils, about 1525 - 1530 Pen and brown ink, brown wash, white from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg heightening Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment 21.6 × 24.3 cm (8 1/2 × 9 9/16 in.) Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 84.GA.9 Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 155 (83.ML.115.155) October 10, 2018 Page 1 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ © 2018 J. -

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of Their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. An overview of Giovanni Morelli’s attributions1 Valentina Locatelli ‘This magnificent picture-gallery [of Dresden], unique in its way, owes its existence chiefly to the boundless love of art of August III of Saxony and his eccentric minister, Count Brühl.’2 With these words the Italian art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli (Verona 1816–1891 Milan) opened in 1880 the first edition of his critical treatise on the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden (hereafter referred to as ‘Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister’). The story of the Saxon collection can be traced back to the 16th century, when Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) was the court painter to the Albertine Duke George the Bearded (1500–1539). However, Morelli’s remark is indubitably correct: it was in fact not until the reign of Augustus III (1696– 1763) and his Prime Minister Heinrich von Brühl (1700–1763) that the gallery’s most important art purchases took place.3 The year 1745 marks a decisive moment in the 1 This article is the slightly revised English translation of a text first published in German: Valentina Locatelli, ‘Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei: Die Galerie zu Dresden. Ein Überblick zu Giovanni Morellis Zuschreibungen’, Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 34, (2008) 2010, 85–106. It is based upon the second, otherwise unpublished section of the author’s doctoral dissertation (in Italian): Valentina Locatelli, Le Opere dei Maestri Italiani nella Gemäldegalerie di Dresda: un itinerario ‘frühromantisch’ nel pensiero di Giovanni Morelli, Università degli Studi di Bergamo, 2009 (available online: https://aisberg.unibg.it/bitstream/10446/69/1/tesidLocatelliV.pdf (accessed September 9, 2015); from here on referred to as Locatelli 2009/II). -

Presents the Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, the First Major Exhibition on the Subject in the United States

(Image captions on page 8) (Los Angeles—April 26, 2018) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, the first major exhibition on the subject in the United States. Organized by LACMA in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, this groundbreaking show brings together some 100 rare and seldom-exhibited chiaroscuro woodcuts alongside related drawings, engravings, and sculpture, selected from 19 museum collections. With its accompanying scholarly catalogue, the exhibition explores the creative and technical history of this innovative, early color printmaking technique, offering the most comprehensive study on the remarkable art of the chiaroscuro woodcut. “LACMA has demonstrated a continued commitment to promoting and honoring the art of the print,” said LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan. “Los Angeles is renowned as a city that fosters technically innovative printmaking and dynamic collaborations between artists, printmakers, and master printers. This exhibition celebrates this spirit of invention and collaboration that the Renaissance chiaroscuro woodcut embodies, and aims to cast new light on and bring new appreciation to the remarkable achievements of their makers.” “Although highly prized by artists, collectors, and scholars since the Renaissance, the Italian chiaroscuro woodcut has remained one of the least understood techniques of early printmaking,” said Naoko Takahatake, curator of Prints and Drawings at LACMA and organizer of the exhibition.