THE ANNALS of IOWA 66 (Winter 2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Civil War & the Northern Plains: a Sesquicentennial Observance

Papers of the Forty-Third Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains “The Civil War & The Northern Plains: A Sesquicentennial Observance” Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 29-30, 2011 Complied by Kristi Thomas and Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-Third Annual Dakota Conference was provided by Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, Tony and Anne Haga, Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour and Grace Hansen-Gilmour, Carol M. Mashek, Elaine Nelson McIntosh, Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College, Rex Myers and Susan Richards, Rollyn H. Samp in Honor of Ardyce Samp, Roger and Shirley Schuller in Honor of Matthew Schuller, Jerry and Gail Simmons, Robert and Sharon Steensma, Blair and Linda Tremere, Richard and Michelle Van Demark, Jamie and Penny Volin, and the Center for Western Studies. The Center for Western Studies Augustana College 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... v Anderberg, Kat Sailing Across a Sea of Grass: Ecological Restoration and Conservation on the Great Plains ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Anderson, Grant Sons of Dixie Defend Dakota .......................................................................................................... 13 Benson, Bob The -

History and Constitution (PDF)

HISTORY AND THE CONSTITUTION Chapter 7 HISTORY AND THE CONSTITUTION 309 EARLY HISTORY OF IOWA By Dorothy Schwieder, Professor of History, Iowa State University Marquette and Joliet Find Iowa Lush and Green In the summer of 1673, French explorers Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette traveled down the Mississippi River past the land that was to become the state of Iowa. The two explorers, along with their five crewmen, stepped ashore near where the Iowa River flowed into the Missis- sippi. It is believed that the 1673 voyage marked the first time that white people visited the region of Iowa. After surveying the surrounding area, the Frenchmen recorded in their journals that Iowa appeared lush, green, and fertile. For the next 300 years, thousands of white settlers would agree with these early visitors: Iowa was indeed lush and green; moreover, its soil was highly produc- tive. In fact, much of the history of the Hawkeye State is inseparably intertwined with its agricul- tural productivity. Iowa stands today as one of the leading agricultural states in the nation, a fact foreshadowed by the observation of the early French explorers. The Indians Before 1673, however, the region had long been home to many Native Americans. Approxi- mately 17 different Indian tribes had resided here at various times including the Ioway, Sauk, Mesquaki, Sioux, Potawatomi, Oto, and Missouri. The Potawatomi, Oto, and Missouri Indians had sold their land to the federal government by 1830 while the Sauk and Mesquaki remained in the Iowa region until 1845. The Santee Band of the Sioux was the last to negotiate a treaty with the federal government in 1851. -

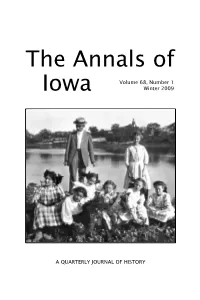

EACH ISSUE of the Annals of Iowa Brings to Light the Deeds, Misdeeds

The Annals of Volume 68, Number 1 Iowa Winter 2009 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue VICTORIA E. M. CAIN, a Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Southern California, recounts the early history (1868–1910) of the Dav- enport Academy of Natural Sciences. She focuses on its transformation from a society devoted to scientific research into a museum dedicated to popular education. PAM STEK, a graduate student in history at the University of Iowa, describes the development in the 1880s and 1890s of a flourishing African American community from the small Iowa coal camp at Muchakinock. She shows how the attitudes and business practices of the coal company executives as well as the presence of strong African American leaders in the community contributed to the formation of an African American community that was not subjected to the enforced segregation, disfranchisement, and racial violence perpetrated against blacks in many other parts of the United States at that time. Front Cover J. H. Paarmann, curator of the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences, led the institution’s transformation from a society devoted to scientific research into a museum dedicated to popular education. Here, Paarmann is seen leading a group of girls on a field trip along the Mississippi River. For more on Paarmann’s role in transforming the Davenport academy, see Victorian E. M. Cain’s article in this issue. Photo courtesy Putnam Museum of History and Natural Science, Davenport, Iowa. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. David Edmunds, University of Texas University at Dallas Kathleen Neils Conzen, University of H. -

New Iowa Materials

NEW IOWA MATERIALS A SUPPLEMENT TO THE THIRD EDITION OF IOWA AND SOME IOWANS Prepared by Betty Jo Buckingham Iowa Department of Education Des Moines, Iowa 1990 State of Iowa DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Grimes State Office Building Des Moines, Iowa 50319-0146 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Karen K. Goodenow, President, Spirit Lake Dianne L.D. Paca, Vice-President, Gamer Betty L. Dexter', Davenport Thomas M. Glenn, Des Moines Francis N. Kenkel, Defiance Ron McGauvran, Clinton Mary E. Robinson, Cedar Rapids Ann W. Wickman, Atlantic George P. Wilson Ill, Sioux City ADMINISTRATION William L. Lepley, Director and Executive Officer of St~ Board of Education David H. Bechtel, Special Ass1stant Mavis Kelley, Special Assistant ... Sue Danielson, Administrator Maryellen Knowles, Acting Chief, Bureau of lnatructlon and Curriculum Betty Jo Buckingham, Consultant, Educational Media NEW IOWA MATERIALS When the Iowa Department of Education published IOWA AND SOME IOWANS in 1988 we pledged to try to keep school library media specialists up to date with smaller bibliographies. One such bibliography is given here. It is by no means inclusive. Many of the titles have not been examined for usefulness. We have tried to include literature and history, elementary and secondary interests. When the item or an annotation was available we have supplied some content information. For a few this was not available. We hope you will write to us about titles you have found useful whatever the format. We would also welcome your comment about these titles and your suggestions for what kind of information about Iowa materials would be most useful to you. Send comments or suggestions to Betty Jo Buckingham, Iowa Department of Education, Grimes State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa 50319. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Wessel, Lynda; Florman, Jean, Ed. Prairie Voices: an Iowa Heritage Curriculum. Iowa State Historical Soci

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 420 580 SO 028 800 AUTHOR Wessel, Lynda; Florman, Jean, Ed. TITLE Prairie Voices: An Iowa Heritage Curriculum. INSTITUTION Iowa State Historical Society, Iowa City.; Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 1995-00-00 NOTE 544p.; Funding provided by Pella Corp. and Iowa Sesquicentennial Commission. AVAILABLE FROM State Historical Society of Iowa, 402 Iowa Avenue, Iowa City, IA, 52240. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC22 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; Community Study; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; *Heritage Education; Instructional Materials; Social History; Social Studies; *State History; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT This curriculum offers a comprehensive guide for teaching Iowa's historical and cultural heritage. The book is divided into six sections including: (1) "Using This Book"; (2) "Using Local History"; (3) "Lesson Plans"; (4) "Fun Facts"; (5) "Resources"; and (6)"Timeline." The bulk of the publication is the lesson plan section which is divided into: (1) -=, "The Land and the Built Environment"; (2) "Native People"; (3) "Migration and Interaction"; (4) "Organization and Communities";(5) "Work"; and (6) "Folklife." (EH) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** Prairie Voices An Iowa Heritage Curriculum State Historical Society of Iowa Des Moines and Iowa City1995 Primarily funded by Pella Corporation in partnership with U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION the Iowa Sesquicentennial Commission Office of Educational Research and Improvement C:) EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) 4Erihis document has been reproduced as C) received from the person or organization IOWA originating it. 00 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. -

THE ANNALS of IOWA 69 (Fall 2010)

The Annals of Volume 69, Number 4 Iowa Fall 2010 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue DOROTHY SCHWIEDER, University Professor Emerati of History at Iowa State University, recounts the life of Jack Trice up until he died in 1923 as a result of an injury he suffered during his second game as the only African American member of the Iowa State College football team. Then she relates the long struggle to rename Iowa State’s football stadium in his honor. In both cases she sets the story in the context of changing racial and social attitudes. JENNY BARKER DEVINE, assistant professor of history at Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois, interprets the programming of Farm Bureau women’s clubs from 1945 to 1970. After nearly three decades of strong state-centered programming, club activities in the postwar period, she concludes, were characterized by a greater focus on local leadership. State leaders continued to advise local clubwomen to engage in activities related to politics, agricultural policy, and the like, but members of town- ship clubs became increasingly selective in responding to state leaders’ advice, focusing more narrowly on their neighborhoods, social events, and new trends in homemaking. Devine interprets this response not as an indicator of resistance or rejection of state leaders but rather as the manifestation of “social feminisms” in the countryside. Front Cover Jack Trice (second from left) poses in uniform with three white teammates from the 1923 Iowa State College football team. For the story of Trice’s life and his legacy at Iowa State, see Dorothy Schwieder’s article in this issue. -

December 9, 2014 (PDF)

Art Bergles Mechanical Engineering Professor Emeritus Art Bergles passed away March 17, 2014 at the age of 78. Dr. Arthur E. Bergles was born in 1935 in New York City. His parents had immigrated to the United States from Austria, and moved to upstate New York after working in Manhattan so Arthur’s father could fulfill his dream of building a hydroelectric power plant. Edward Bergles was a self-taught engineer and successfully built the plant, which ran for 47 years with help from Art. Art took an interest in engineering at an early age, and after graduating as valedictorian of his high school class, as well as an accomplished athlete and Eagle Scout, he enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). While at MIT, Art earned a combined Bachelor’s/Master’s degree and Ph.D. in mechanical engineering, spent a year as a Fulbright Scholar in Munich, Germany, and taught as an assistant professor in the mechanical engineering department. During his time at MIT, Art also met his wife Priscilla (Penny) who was a student at Boston University. Art left MIT to work at the Georgia Institute of Technology as a Professor, before becoming Chair of the Mechanical Engineering Department and Anson Marston Distinguished Professor of Engineering at Iowa State. Art was recognized as one of the world’s leading experts in thermal sciences and published 26 books, more than 400 papers and gave more than 400 invited lectures. He advised 82 thesis students during his career, and was passionate about helping young engineers become successful. The Bergles professorship was established through an endowment from Art and Penny, and is currently held by Dr. -

Writing the Midwest: a Symposium of Scholars and Creative Writers” to Be Held June 2–4, 2016 (Thursday–Saturday) at Michigan State University

Midwestern History Association MHA Newsletter -- September 2015 Dear Friends of Midwestern History – Best wishes to you as fall approaches and as many of you are returning to your classrooms. The Midwestern History Association took a newsletter break during the August doldrums and so we now have lots to report to you on our activities as we approach the one year anniversary of our formal creation on October 11, 2014. As always, we greatly encourage you to share this newsletter with your friends and colleagues and let them know of our activities. I am going to begin this newsletter by sharing the latest on the prize front since some important deadlines are looming: Book Prize: Professor Andrew Cayton, now of The Ohio State University, is the chair of this year’s annual Jon Gjerde book prize committee for the best book written about Midwestern history during the calendar year 2014. Drew recently reported the list of book award nominees to the MHA and they are revealed below (addendum 1). This year’s book prize winner will be announced within the next month or so. Article Prize: Dr. Catherine Cocks of the University of Iowa Press is the chair of this year’s annual Dorothy Schwieder Prize for the best academic article written about Midwestern history during the calendar year 2014. Catherine recently reported the list of article award nominees to the MHA and they are revealed below (addendum 2). This year’s article prize winner will be announced in coming weeks. Turner Prize: The deadline recently passed for nominations for the annual Frederick Jackson Turner Prize for Distinguished Career Contributions to Midwestern History. -

THE ANNALS of IOWA 67 (Fall 2008)

The Annals of Volume 67, Number 4 Iowa Fall 2008 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue DEREK R. EVERETT offers a full account of the “border war” between Iowa and Missouri from 1839 to 1849, expanding the focus beyond the usual treatment of the laughable events of the “Honey War” in 1839 to illustrate the succession of events that led up to that conflict, its connection to broader movements in regional and national history, and the legal and social consequences of the controversy. Derek R. Everett teaches history at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. NOAH LAWRENCE tells the story of Edna Griffin and her struggle to desegregate the Katz Drug Store in Des Moines in 1948. His account re- veals that Griffin was a radical black activist who was outspoken through- out her life about the need for economic and racial justice, yet her legal strategy during the trial constructed her as a “respectable” middle-class mother rather than as a firebrand activist. Noah Lawrence is a high school history teacher at Hinsdale Central High School in Hinsdale, Illinois. Front Cover Protesters picket outside Katz Drug Store in Des Moines in 1948. Many of the signs connect the struggle for desegregation to the fight against Nazi Germany during World War II. For more on the struggle for desegregation in Des Moines, see Noah Lawrence’s article in this issue. This photograph, submitted as evidence in the Katz trial and folded into the abstract, was provided courtesy of the University of Iowa Law Library, Iowa City. (For a full citation of the abstract, see the first footnote in Lawrence’s article.) Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. -

The Human Brain Begins to Work the Moment

A Peculiar People Revisited: Demographic Foundations of the Iowa Amish in the 21st Century – Cooksey and Donnermeyer A Peculiar People Revisited: Demographic Foundations of the st Iowa Amish in the 21 Century1 Elizabeth C. Cooksey2 Professor, Department of Sociology, and Associate Director, Center for Human Resource Research The Ohio State University Joseph F. Donnermeyer Professor of Rural Sociology School of Environment and Natural Resources The Ohio State University Abstract This article describes the demographic foundations of the Amish in Iowa. We note that since the publication of “A Peculiar People” by Dorothy and Elmer Schwieder in 1975 (with an updated version in 2009) the demographic dynamics of the Amish have changed little. They remain a high fertility group, and, when coupled with increases in their retention of daughters and sons in the Amish faith, the Amish are currently experiencing rapid population increase and settlement growth. In turn, the occupational base of the Amish has become more diverse and less reliant on agriculture. We observe that the first or founding families for new settlements in Iowa come equally from outside of Iowa and older settlements within the Hawkeye state. Keywords: settlement, community, migration, fertility, Amish, Iowa 110 | Page Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies, Volume 1, Issue 1 (April), 2013 Introduction In 1975, Dorothy and Elmer Schwieder published “A Peculiar People, Iowa’s Old Order Amish” where the term “peculiar” was used in the biblical sense of the word to mean “particular” or “special,” rather than today’s more common understanding of “strange” or “eccentric.” In 2009, with the addition of an essay that includes updates from the 2004 Iowa Amish Directory by Thomas Morain, the book was re-issued by the University of Iowa Press (Schwieder and Schwieder 2009). -

Educator Manual

HISTORY KITS Identity TEACHER MANUAL GOLDIE’S HISTORY KIT INTRODUCTION Table of Contents Goldie’s History Kit Introduction and Instructions ............................................................... 3 Read Iowa History ..................................................................... 5 • Introduction to Read Iowa History .............................................................6 • Compelling and Supporting Questions .........................................................8 • Standards and Objectives .....................................................................9 • Background Essay ..........................................................................10 Pre-Lesson Activity 1: Defining “Unique” and Creating a Self Portrait ..............................11 • Worksheet, Self Portrait .....................................................................12 Pre-Lesson Activity 2: Question Formulation Technique (QFT) ....................................13 • Image, Children Waiting in Line for Water in Yauco, Puerto Rico ...................................14 Part 1: Applying QFT to Analyze Maps ..........................................................15 • Primary Sources ............................................................................17 • Worksheets ................................................................................21 Part 2: Telling Your Story with Objects and Images ..............................................23 • Primary Sources ............................................................................25 -

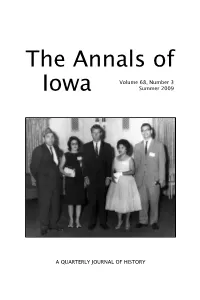

The Annals of Iowa Volume 68, Number 3

The Annals of Volume 68, Number 3 Iowa Summer 2009 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue JANET WEAVER, assistant curator at the Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries, traces the emerging activism of a cadre of second-generation Mexican Americans in Davenport. Many of them grew up in the barrios of Holy City and Cook’s Point in the 1920s and 1930s. By the late 1960s, they were providing local leadership for Cesar Chavez’s grape boycott campaign and lending their support to the fiercely contested passage of Iowa’s first migrant worker legislation. KARA MOLLANO analyzes the campaign led by minority residents of Fort Madison in the 1960s and 1970s to oppose a plan to rebuild U.S. High- way 61 that would have included rerouting the road through neighbor- hoods disproportionately inhabited by African Americans and Mexican Americans. The multiracial and multiethnic coalition succeeded in block- ing the highway plan while exposing racial, ethnic, and class divisions in Fort Madison. Front Cover Ernest Rodriguez (right) was born in a boxcar in Davenport’s “Holy City” in 1928. By 1963, he was meeting with U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy (center) at the American GI Forum convention in Chicago , along with (left to right) Augustine Olvera, Mary Olvera, and Juanita Rodriguez. For more on the emerging activism of Davenport’s Mexican Americans “from barrio to ‘¡boicoteo!’ see Janet Weaver’s article in this issue. Photo courtesy Ernest Rodriguez. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. David Edmunds, University of Texas University at Dallas Kathleen Neils Conzen, University of H.