The Language of Vultures Byron Kerr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosa Katz: Oral History Transcript

Rosa Katz: Oral History Transcript www.wisconsinhistory.org/HolocaustSurvivors/Katz. asp Name: Rachel (Rosa) Goldberg Katz (1924–2012) Birth Place: Lodz, Poland Arrived in Wisconsin: 1953, Oshkosh Project Name: Oral Histories: Wisconsin Survivors Rosa Katz of the Holocaust Biography: Rachel (Rosa) Goldberg Katz was born in Lodz, Poland, on May 6, 1924, to a well-to-do family with liberal Jewish beliefs. In 1935, her sister and brother-in-law immigrated to Palestine while the rest of the family remained in Poland. When the Germans occupied Lodz in 1939, 15-year-old Rosa was among the thousands of Jews crowded into the city's ghetto. Three years later, in July 1942, her mother was deported from the ghetto and never heard from again. In August 1944, the Lodz Ghetto was liquidated. Its starving residents, including Rosa, her father, brother, and sister-in-law, Hela, were all shipped to Auschwitz. There she was separated from her father and brother. She never saw them again. German officials mistakenly sent Rosa and hundreds of other Jewish women (instead of French prisoners) to work at the Krupp munitions factory in Berlin. For eight months, Rosa assembled delicate timepieces for German bombs. In March 1945, she was transferred to the death camp in Ravensbruck, Germany. The Swedish Red Cross liberated the camp within a month of her arrival. Its inhabitants were transported to Sweden where Rosa recuperated for several years. She married Bernard Katz there (also a survivor). In April 1948, they came to the U.S. Initially settling in North Carolina, the Katz family moved to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in 1953. -

Banner Roundo) 2

Il =' II I-·I·III--· I- I II · I -- - I --- L- Ir I , · -'--r- · I - I · I 2 CAZIING HOME FOR MONEY TUST GOT CHEAPER. r ^M~~rli~ftlilll~~l^Jinl~~lia~~iI~syilli^^ii~~~nj~ia~gjiiiTT^^~ Now there's a cheaper way to call home-or anywhere else. coin and collect calls. You can even use your Home Federal Just buy a Pre-Paid Phone Card at BASED ON A 3 MINUTE CALL FROM NEW YORK TO: Pre-Paid Phone Card for cellular a\ our branch on campus or your Pay Phone AT&T Home Federal phone calls and pagers. At a\ Credit Card Phone Card r- nearest Home Federal branch. Anywhere in the U.S. $5.50 $3.41 $0.75 Home Federal, you don't have France, Germany, Norway, $12.60 $7.44 $1.50 E You'll enjoy savings of 40-70% Sweden, Switzerland and U.K. to go far to call far-for less. Just Italy $19.50 $9.65 $2.25 IQ) on pay phone and credit card Korea $19.50 $8.78 $4.00 think of what you can do with O Brazil $11.30 $11.24 $4.00 O long distance rates, and 150%o on all that spare change. $.- 0 516-689-8900 Student Activities Center, Lower Level Monday-Friday 9:00AM-4:30PM, Thursdays 9:00AM-7:00PM di o c> (&I0 4-^0 <^ YOu DON'T HAVE To CO FAR To GET FAR:m * < $4 I;'eniber r)IC 31 CONVENIENT BRANCH LOCATIONS THROUGHOUT BROOKLYN, QUEENS, NASSAU, SUFFOLKAND STATEN ISLAND EQUALHOUSING LENDER k-I I 3 at lIving Pla za Sold~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1Sold OuJrsOut Jars of ClaClay ConerConcert L at Irin zt7a BY DIANA GINGO through the set with energy and strong lead Statesmant Editor _ _ vocals. -

Cedars, January 21, 2000 Cedarville College

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 1-21-2000 Cedars, January 21, 2000 Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "Cedars, January 21, 2000" (2000). Cedars. 727. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/727 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January 21, 200 oe Stowell..................... 2 Drunk with Marty Ph.Ds......................3 .....................2 Senior Recitalists............. 4 Cedar Faces.................... 5 Well-oiled Honors Band...................7 machines Graves on Worship........... 8 ••••••••• a**** 5 Music Reviews................. 9 Flock flies north Women's Basketball........10 Men's Basketball............ 11 .................... 7 A CEDARVILLE COLLEGE STUDENT PUBLICATION Sidewalk Talk................. 12 CCM star Chris Rice performs on campus again Kristin Rosner but not the sophistication that Staff Writer often comes with the success that Rice has experienced lately. -

The Song of the Lark I

HE ONG OF THE ARK T S L BY WILLA CATHER © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2010 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Winter-75-76-OCR Opt

POETRY + NORTHWEST VOLUME SIXTEEN NUMBER FOUR EDITOR David Wagoner WINTER 1975-76 THOMAS BRUSH EDITQRIAL CQNsULTANTs Four Poems Nelson Bentley, William Matchett JOHN ALLMAN Three Poems, CovER DEsIGN ALBERT GOLDBARTH Allen Auvil The Chariots /The Gods . KIM STAFFORD historic marker . I l JACK ANDERSON I Faith 12 Cover from a photograph of a Weyerhaeuser Company clear-cut in the W; R. MOSES foothills of the Cascade Mountains by James 0. Sneddon. Three Poems . DONALD A. PETESCH Isadora and the Head from the Feet Manuscript . 1 7 / I G. E. MURRAY Shopping for Midnight. 18 ARTHUR VOGELSANG BOARD OF ADVISERS ,I Another Fake Love Poem Leonie Adams, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert B. Heilman, 19 Stanley Kunitz,Jackson Mathews, Arnold Stein CHARLES VANDERSEE Sculpture 20 ROBERT PACK POETRY NORTHWEST W I N TER 1975-76 VOLUME XVI, NUMBER 4 Advice to the Traveler . 21 Published quarterly by the University of Washington. Subscriptions and manu G. S. SHARAT CHANDRA scripts should be sent to poetry Northwest, 4045 Brooklyn Avenue NE, Univer Two Poems. sit y of Washington Seattle Washington,98195. Not responsible for unsolicited 22 manuscripts;all submissions must be accompanied by a stampeded self-addressed JOHN ENGMAN envelope.Subscription rate $4.50 per year; single copies, $1.50. Two Poems. 26 © 1976 bythe University of Washington HENRY CARLILE Butchering Crabs . 27 Distributed by B. DeBoer, 188 High Street, Nutley, N J 07110 and m the NAOMI CLARK West by L-S Distributors, 1161 Post Street, San Francisco, Calif. 9410 Cygnus XI . 29 MARC HUDSON POETRY Village. N ORTH~ E S T ANDREW GROSSBARDT W IN T E R 1 9 7 5 - 7 6 No One Has Done That Before 32 JOHN TAYLOR Fog at the Windows. -

The World's Largest Selection of Christian Songbooks!

19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 1 The world’s largest selection of Christian songbooks! Hal Leonard is proud to be the distributor for Nashville-based Brentwood-Benson. Their extensive catalog offers something for everyone – great new releases from the hottest CCM artists to traditional and contemporary gospel collection. This brochure features just a sampling of Brentwood-Benson’s outstanding artist collections, song compilations, and songbook series. All of these titles are in stock and ready for you to order! Contact your Hal Leonard sales representative to place your order and find out about our Brentwood-Benson special offer! Call the E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626 Send a message to [email protected] or visit www.halleonard.com/dealers 19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 2 MIXED FOLIOS Amazing Wedding Songs Top 100 Praise and Worship Top 100 Praise & Worship Top 100 Southern Gospel 30 of the Most Requested Songs – Volume 2 Songbook Songbook BRENTWOOD-BENSON Songs for That Special Day This guitar chord songbook includes: Ah, Lord Guitar Chord Songbook Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- Book/CD Pack God • Celebrate Jesus • Glorify Thy Name • Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- grams for 100 classics, including: Because He Listening CD – 5 songs Great Is Thy Faithfulness • How Majestic Is grams for 100 songs, including: As the Deer • Lives • Daddy Sang Bass • Gettin’ Ready to ✦ Includes: Always • Ave Maria • Butterfly Your Name • In the Presence of Jehovah • My Come, Now Is the Time to Worship • I Could Leave This World • He Touched Me • In the Kisses • Canon in D • Endless Love • I Swear Savior, My God • Soon and Very Soon • Sing of Your Love Forever • Lord, I Lift Your Sweet By and By • I’ve Got That Old Time • Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Love Will Be Victory Chant • We Have Come into This Name on High • Open the Eyes of My Heart • Religion in My Heart • Just a Closer Walk with Our Home • Ode to Joy • The Keeper of the House • and many more! Rock of Ages • and dozens more. -

Outspoken Essays (Second Series)

;co -co :co OUTSPOKEN ESSAYS (SECOND SEEIES) BY THE SAME AUTHOR OUTSPOKEN ESSAYS. First Series. Crown 8vo. 6s. net. THE PHILOSOPHY OF PLOTINUS. The Gifford Lectures at St. Andrews, 1917-1918. 2 vols. 8vo. 28s. net. SPECULUM ANIMAE: Four Devotional Addresses given in the Chapel of Corpus Christ! College, Cambridge, to Public Schoolmasters and College Tutors. Fcp. 8vo. 3s. net. THE CHURCH AND THE AGE: Four Lectures delivered at Sion College to the Women's Diocesan Association on ' The Co-operation of the Church with the Spirit of the Age.' Fcp. 8vo. 3s. net. AUTHORITY AND THE INNER LIGHT. Crown 8vo. 9d. net. LONGMANS, GBEEN, AND CO. LONDON, NEW YORK, AND TORONTO BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS OUTSPOKEN ESSAYS (SECOND SERIES) BY WILLIAM KALPH INGE, C.V.O., D.D., F.BA. DEAN OF ST. PAUL'S LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO 39 PATEENOSTEB BOW, LONDON, E.G. 4. NEW YORK, TORONTO BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS 1922 All rights reserved Made in Great Britain PREFACE IT is always difficult to choose a title for a book of essays, and it seemed most convenient to repeat the name of the little volume which was published three years ago. Those essays were in part a challenge to certain idols of the market-place and theatre, and I thought it legitimate to mark the purpose or tendency of the book on the title- page. But I have no wish to pose as a prophet crying in the wilderness. The events of the last few years have, it is to be hoped, taught something both to my critics and to have even us nearer myself ; they perhaps brought together. -

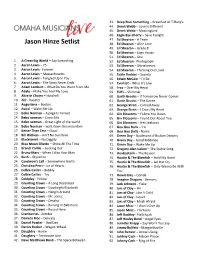

Current Setlist

43. Deep Blue Something – Breakfast At Tiffany’s 44. Derek Webb – Love Is Different 45. Derek Webb – Mockingbird 46. Eagle Eye Cherry – Save Tonight 47. Ed Sheeran – A Team Jason Hinze Setlist 48. Ed Sheeran – Afire Love 49. Ed Sheeran – Grade 8 50. Ed Sheeran – Lego House 51. Ed Sheeran – One 1. A Great Big World – Say Something 52. Ed Sheeran - Photograph 2. Aaron Lewis – 75 53. Ed Sheeran – Shirtslieeves 3. Aaron Lewis - Forever 54. Ed Sheeran – Thinking Out Loud 4. Aaron Lewis – Massachusetts 55. Eddie Vedder – Society 5. Aaron Lewis – Tangled Up In You 56. Edwin McCain – I’ll Be 6. Aaron Lewis – The Story Never Ends 57. Everlast – What It’s Like 7. Adam Lambert – What Do You Want From Me 58. Fray – Over My Head 8. Adele – Make You Feel My Love 59. FUEL – Shimmer 9. Alice In Chains – Nutshell 60. Garth Brooks – If Tomorrow Never Comes 10. AIC - Rooster 61. Garth Brooks – The Dance 11. Augustana – Boston 62. George Strait – Carried Away 12. Avicci – Wake Me Up 63. George Strait – I Cross My Heart 13. Bebo Norman – A page Is Turned 64. Gin Blossoms – Follow You Down 14. Bebo norman – Cover Me 65. Gin Blossoms – Found Out About You 15. Bebo norman – Great Light of the world 66. Gin Blossoms – Hey Jealousy 16. Bebo Norman – walk down this mountain 67. Goo Goo Dolls – Iris 17. Better Than Ezra – Good 68. Goo Goo Dolls - Name 18. Bill Withers – Ain’t No Sunshine 69. Green Day – Boulevard of Broken Dreams 19. Blackstreet – No Diggity 70. Green Day – Good Riddance 20. -

Jars of Clay Much Afraid Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jars Of Clay Much Afraid mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Much Afraid Country: US Released: 1997 Style: Alternative Rock, Acoustic MP3 version RAR size: 1108 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1116 mb WMA version RAR size: 1925 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 198 Other Formats: AHX DTS AAC MOD APE AUD VQF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Overjoyed 2:59 2 Fade To Grey 3:34 Tea & Sympathy 3 Arranged By [String Orchestration] – Richard NilesConductor – Gavyn WrightStrings – The 4:52 London Session Orchestra 4 Crazy Times 3:34 Frail 5 6:57 English Horn – Kate St. John Five Candles (You Were There) 6 3:48 Drums – Neil Conti 7 Weighed Down 3:39 8 Portrait Of An Apology 5:42 9 Truce 3:11 10 Much Afraid 3:52 11 Hymn 3:56 Credits Arranged By [String Orchestration] – Ron Huff* (tracks: 2, 5, 8, 11) Drums, Percussion, Bass – Greg Wells (tracks: 1 to 5, 7 to 10) Engineer, Mixed By – Heff Moraes Executive Producer – Robert Beeson Mastered By – Stephen Marcussen Producer – Stephen Lipson Notes Recorded at The Aquarium, London, UK, and at Secret Sound, Franklin, TN. This release contains two tracks ('Frail' and 'Fade To Grey') that originally appeared on the band's demo and were re-recorded for this album. 'Frail', orignally an instrumental, had lyrics added for this version. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 20831-2216-2 7 6 3 Matrix / Runout: CPDX-000900 F4 1A 08 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Jars Of Much Afraid (CD, Essential CD70017 CD70017 US 1997 Clay Album) Records Essential Jars Of Much Afraid -

Tom Swift and His Air Glider Or Seeking the Platinum Treasure

Tom Swift and His Air Glider or Seeking the Platinum Treasure by Victor Appleton 1912 2 Contents 1 A BREAKDOWN 5 2 A DARING PROJECT 11 3 THE HAND OF THE CZAR 17 4 THE SEARCH 21 5 A CLEW FROM RUSSIA 25 6 RESCUING MR. PETROFSKY 31 7 THE AIR GLIDER 35 8 IN A GREAT GALE 39 9 THE SPIES 43 10 OFF IN THE AIRSHIP 47 11 A STORM AT SEA 51 12 AN ACCIDENT 55 13 SEEKING A QUARREL 59 14 HURRIED FLIGHT 63 15 PURSUED 67 16 THE NIHILISTS 73 17 ON TO SIBERIA 77 18 IN A RUSSIAN PRISON 81 19 LOST IN A SALT MINE 85 3 4 CONTENTS 20 THE ESCAPE 89 21 THE RESCUE 93 22 IN THE HURRICANE 99 23 THE LOST MINE 103 24 THE LEAKING TANKS 109 25 HOMEWARD BOUND—CONCLUSION 113 Chapter 1 A BREAKDOWN “Well, Ned, are you ready?” “Oh, I suppose so, Tom. As ready as I ever shall be.” “Why, Ned Newton, you’re not getting afraid; are you? And after you’ve been on so many trips with me?” “No, it isn’t exactly that, Tom. I’d go in a minute if you didn’t have this new fangled thing on your airship. But how do you know how it’s going to work—or whether it will work at all? We may come a cropper.” “Bless my insurance policy!” exclaimed a man who was standing near the two lads who were conversing. “You’d better keep near the ground, Tom.” “Oh, that’s all right, Mr. -

< Cries & Whispers >

LESSON 1 HANDOUT < cries & whispers > A. I wish I wasn’t so much afraid of growing up. – Joanna B. My parents got divorced, and it took a toll on my schooling, my grades, and basically my life was twisted upside down really quickly. – Hannah C. I basically had to raise myself. – John D. It seemed like every day was getting worse. – Hannah E. I wish that I could have the normal family that you see all the time on TV. – Shade F. It’s really hard to have all those responsibilities and still be young. – Joanna G. Living with my mom can be hard, day to day. There are things that we just don’t get along about. – Kimberly H. I think I was mad at God. And I thought, “God, why are you punishing me? Why are you being mean to me? And of all of the kids why are you picking on me?” – Hannah I. I didn’t really understand: How is this great hurt in my life going to help people? – Alina J. I felt like I didn’t have any self worth. I felt that I wasn’t worthy to be cared for, you know. Like, for some reason I just wasn’t good enough to be loved. – John A statement that could have been said by someone I know: What I might say in response to that person: The statement that’s most like the way I feel: Re-phrase that statement in your own words: free downloadable videos at revolution 2 www.bluefishtv.com LESSON 2 HANDOUT < dear gabby > 1 Dear Gabby, My dad pays no attention to me.