Geopolitics of Artivism Evaluation of Artivism in the Art and Media Domain in Cross-National Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Andrej Sakharov 19 Elena Bonner, Compagna Di Vita 21

a cura di Stefania Fenati Francesca Mezzadri Daniela Asquini Presentazione di Stefania Fenati 5 Noi come gli altri, gli altri come noi di Simonetta Saliera 9 L’Europa è per i Diritti Umani di Bruno Marasà 13 Il Premio Sakharov 15 Andrej Sakharov 19 Elena Bonner, compagna di vita 21 Premio Sakharov 2016 25 Nadia Murad Basee Taha e Lamiya Aji Bashar, le ragazze yazide Premio Sakharov 2015 35 Raif Badawi, il blogger che ha criticato l’Arabia Saudita Premio Sakharov 2014 43 Denis Mukwege, il medico congolese che aiuta le donne Premio Sakharov 2013 53 Malala Yousafzai, la ragazza pakistana Premio Sakharov 2012 59 Jafar Panahi, il regista indiano Nasrin Sotoudeh, l’avvocatessa iraniana Premio Sakharov 2011 69 Mohamed Bouazizi - Asmaa Mahfouz - Ali Ferzat - Razan Zaitouneh - Ahmed Al-Sanusi - Le donne e la Primavera araba Glossario 89 Carta dei Diritti Fondamentali dell’Unione Europea 125 Presentazione Stefania Fenati Responsabile Europe Direct Emilia-Romagna Il Premio Sakharov rappresenta un importante momento nel quale ogni anno, dal 1988 ad oggi, la voce dell’Unione europea si fa senti- re contro qualsiasi violazione dei diritti umani nel mondo, e riafferma la necessità di lavorare costantemente per il progresso dell’umanità. Ogni anno il Parlamento europeo consegna al vincitore del Premio Sakharov una somma di 50.000 euro nel corso di una seduta plena- ria solenne che ha luogo a Strasburgo verso la fine dell’anno. Tutti i gruppi politici del Parlamento possono nominare candidati, dopodi- ché i membri della commissione per gli affari esteri, della commis- sione per lo sviluppo e della sottocommissione per i diritti dell’uomo votano un elenco ristretto formato da tre candidati. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

LILY VAN DER STOKKER Born 1954 in Den Bosch, the Netherlands Lives and Works in Amsterdam and New York

LILY VAN DER STOKKER Born 1954 in Den Bosch, the Netherlands Lives and works in Amsterdam and New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2014 Huh, Koenig & Clinton, New York Hello Chair, Air de Paris, Paris 2013 Sorry, Same Wall Painting, The New Museum, New York 2012 Living Room, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan 2011 Not so Nice, Helga Maria Klosterfelde Editions, Berlin 2010 Terrible and Ugly, Leo Koenig Inc., New York No Big Deal Thing, Tate St. Ives, Cornwall, UK (cat.) Terrible, Museum Boijmans, Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Flower Floor Painting, La Conservera, Ceuti/Murcia, Spain (cat.) 2009 Dorothy & Lily fahren boot, Paris-Berlin: Air de Paris chez, Esther Schipper, Berlin 2005-07 De Zeurclub/The Complaints Club, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands 2005 Air de Paris, Paris Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA Family, Money, Inheritance, Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan Furniture Project, Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan 2004 Oom Jan en Tante Annie, one year installation in Cupola of Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, the Netherlands (cat.) Lily van der Stokker - Wallpaintings, Feature Inc., New York, with Richard Kern Tafels en stoelen, VIVID vormgeving, Rotterdam, the Netherlands Feature Inc., New York 2003 Beauty, Friendship and Old Age, Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Arnhem, the Netherlands Small Talk, Performative Installation # 2, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany, (cat.) Easy Fun, Galerie Klosterfelde, Berlin 2002 Air de Paris, Paris, with Rob Pruitt Galleria Francesca -

Miller High Life Theatre Event Advisory

ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER WEBSITE 500 W. Kilbourn Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53203 414.908.6000 MillerHighLifeTheatre.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sarah Maio [email protected] 414-908-6056 King Crimson Announce “Music Is Our Friend” North American Tour Dates 2021 King Crimson comes to the Miller High Life Theatre on August 31, 2021 MILWAUKEE – (June 7, 2021) – The Miller High Life Theatre and Alternative Concert Group are proud to welcome King Crimson with special guest The Zappa Band to the Miller High Life Theatre, August 31, 2021. Artist VIP presale is June 9 at 11 a.m., and venue presale is June 10th at 10 a.m. Tickets go on sale to the public Friday, June 11 at noon at the Miller High Life Theatre box office or Ticketmaster. When King Crimson returns to action this July, it will be the seventh year that the band has toured since returning to performing live in 2014, a run only interrupted by the lockdown in 2020. In that time, the audience has been reinvented, as much as the band itself, something Robert Fripp noted after the band’s performance in Pompeii, Italy’s famous amphitheater: “In Pompeii, a large percentage of the audience was young couples; KC moved into the mainstream in Italy. I walked onstage knowing that this band's position in the world has changed level.” - Robert Fripp The band’s shows regularly include material from twelve of their thirteen studio albums, including many songs from their seminal 1969 album In the Court of the Crimson King, described by Pete Townshend as an “uncanny masterpiece.” The 7-piece line-up play many historic pieces, which Crimson has never previously played live, as well as new arrangements of Crimson classics – “the music is new whenever it was written.” There are also new instrumentals and songs, as well as compositions by the three drummers, Pat Mastelotto, Gavin Harrison and Jeremy Stacey, which are a regular highlight. -

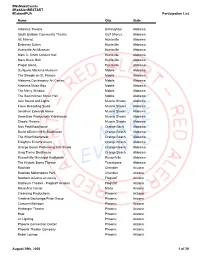

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

In New Iranian Cinema

UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA STUDIES MASTER THESIS RETHINKING THE ’TYPICAL’ IN NEW IRANIAN CINEMA A STUDY ON (FEMALE) REPRESENTATION AND LOCATION IN JAFAR PANAHI’S WORK Master in Film and Media Studies Thesis supervisor: Dr. Gerwin van der Pol 2nd reader: Dr. Emiel Martens Date of Completion: 20th May 2019 i ABSTRACT Contemporary Iranian cinema has been acknowledged and praised by film critics, festivals and audiences worldwide. The recent international acclaim that Iranian films have received since the late 1980s, and particularly through the 1990s, show the significance that the films’ exhibition and reception outside Iran has played in the transformation of cinema in Iran, developing certain themes and aesthetics that have become known to be ‘typical’ Iranian and that are the focus of this paper. This survey explores Iranian film culture through the lens of Jafar Panahi and the poetics of his work. Panahi’ films, in past and present, have won numerous prizes within the international festival circuit and have been interpreted by audiences and critics around the world. Although officially banned from his profession since 2010, the Iranian filmmaker has found its ‘own’ creative ways to circumvent the limitations of censorship and express its nation’s social and political issues on screen. After providing a brief historical framework of the history of Iranian cinema since the 1990s, the survey will look at Panahi’s work within two categories. Panahi’s first three feature films will be explored under the aspects of Iranian children’s films, self-reflexivity and female representation(s). With regards to Panahi’s ‘exilic’ position and his current ban on filmmaking, the survey will analyze one of Panahi’s recent self-portrait works to exemplify the filmmaker use of ‘accented’ characteristics in terms of authorship and the meaning of location (open and closed spaces). -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Passie of professie. Galeries en kunsthandel in Nederland Gubbels, T. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Gubbels, T. (1999). Passie of professie. Galeries en kunsthandel in Nederland. Uniepers. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Adrichem (1991) ASK als beleidsinstrument (1978) Bibliografie J. van Adrichem, Het Rotterdams ASK als beleidsinstrument. In: kunstklimaat: particulier initiatief en Informatiebulletin Raad voor de Kunst, Boeken, rapporten en tijdschrift overheidsbeleid. In: J.C Dagevos, P.C. 1978 (juni) nr. 6. artikelen van Druenen, P. Th. van der Laat (red.) Kunst-zaken: particulier initiatief en Beek (1988) Abbing(1998) overheidsbeleid in de wereld van de A. Beek, Le Canard: cultureel trefpunt H. -

Taxi, Un Jafar Panahi En Roue Libre Dans Le Marasme Téhéranais Hanieh Ziaei

Document generated on 09/27/2021 10:20 a.m. TicArtToc Diversité/Arts/Réflexion(s) Taxi, un Jafar Panahi en roue libre dans le marasme téhéranais Hanieh Ziaei « Clandestino » : créer en marge Number 6, Spring 2016 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/86872ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Diversité artistique Montréal (DAM) ISSN 2292-101X (print) 2371-4875 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Ziaei, H. (2016). Taxi, un Jafar Panahi en roue libre dans le marasme téhéranais. TicArtToc, (6), 32–35. Tous droits réservés © Hanieh Zahieh, 2016 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ) s ( réflexion Taxi, un Jafar Panahi en roue libre dans le marasme téhéranais Hanieh Ziaei petite fille de dix ans, nièce du réalisateur (Hana Saïdi), Dans son dernier film, Jafar Panahi nous invite dans un taxi téhéranais, dans lequel les passagers successifs la célèbre avocate engagée, Nasrin Sotoudeh, un ancien partagent leurs opinions sur le pouvoir d’État, et ce, en voisin et ami de longue date, une institutrice, un voleur, évoquant chacun une facette différente de la société un vendeur de films et de musique piratés, un étudiant iranienne. Ce docufiction fut cependant critiqué par la en cinéma, un enfant de la rue, un homme blessé après jeune génération, qui lui reprocha d’avoir donné une un accident de moto et sa compagne et enfin deux vieilles vision erronée, caricaturale et simpliste de la société. -

Archief Perscombinatie 1966-20081973-1988

Archief Perscombinatie 1966-20081973-1988 Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid (Perscollectie) Postbus 1060 1200 BB Hilversum Nederland hdl:10622/ARCH04311 © IISG Amsterdam 2021 Archief Perscombinatie 1966-20081973-1988 Inhoudsopgave Archief Perscombinatie...................................................................................................................... 5 Archiefvorming....................................................................................................................................5 Inhoud en structuur............................................................................................................................5 Raadpleging en gebruik.....................................................................................................................6 Inventaris............................................................................................................................................ 6 DIRECTIE PERSCOMBINATIE....................................................................................................6 Algemeen............................................................................................................................. 6 Jaarverslagen....................................................................................................................... 7 Correspondentie........................................................................................................7 Vergaderstukken ( hoofddirectie/raad van bestuur)..................................................7