Mizo Studies July - September 2020 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Volume III Issue II Dec2016

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume III Issue 2 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor-in-Chief : Prof. Margaret L. Pachuau Editor : Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. Cherrie L. Chhangte Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof.Jharna Sanyal,University of Calcutta Prof.Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof.Desmond Kharmawphlang,NEHU Shillong Prof.B.K.Danta,Tezpur University Prof.R.Thangvunga,Mizoram University Prof.R.L.Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies EDITORIAL It is with great pleasure that I write the editorial of this issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Culture Studies. Initially beginning with an annual publication, a new era unfolds with regards to the procedures and regulations incorporated in the present publication. The second volume to be published this year and within a short period of time, I am fortunate with the overwhelming response in the form of articles received. This issue covers various aspects of the political, social and cultural scenario of the North-East as well as various academic paradigms from across the country and abroad. Starting with The silenced Voices from the Northeast of India which shows women as the worst sufferers in any form of violence, female characters seeking survival are also depicted in Morrison’s, Deshpande’s and Arundhati Roy’s fictions. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Understanding the Breakdown in North East India: Explorations in State-Society Relations

Working Paper Series ISSN 1470-2320 2007 No.07-83 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan Published: May 2007 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Web site: www.lse.ac.uk/depts/destin 1 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan DESTIN, London School of Economics 1. Introduction Northeastern India – a compact region made up of seven sub-national states1- has historically seen high levels of violence, stemming mostly from ethnic and separatist conflicts. It was among the first of the regions, to demonstrate, on the attainment of Independence, signs of severe political crisis in the form of nationalist movements. This has translated into a string of armed separatist movements and inter-group ethnic conflicts that have become the enduring feature of its politics. Separatist rebellions broke out first in Naga Hills district of erstwhile Assam State, to be followed by similar armed movement in the Lushai Hills district of that State. Soon secessionism overtook Assam proper and in Tripura and Manipur. Of late Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh have joined the list of States that are characterised as unstable and violent. Despite the attempts of both the state and society, many of these violent movements have continued to this day with serious implications for the welfare of citizens (Table 1). Besides separatist violence, inter-group ethnic clashes have been frequent and have taken a heavy toll of life and property.2 Ethnic violence exists alongside inter-ethnic contestations, over resources and opportunities, in which the state finds itself pulled in different directions, with little ability to provide solutions. -

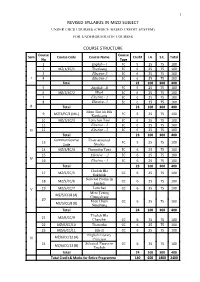

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

SOP Return Thar 15.05.2020

No.B. L3O21/ 1O5 l2O2O-DMR GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM DISASTER MANAGEMENT & REHABILITATION DEPARTMENT **** Aizawl, the 75th of Mag, 2O2O CIRCULAR Mtzoratn mi leh sa India ram hmundanga tangkangte 1o haw dan tur ssCOVID- leh 1o dawnsawn dan turah mumal zawka hma lak anih theih nan 79 Lockdown Aaanga Mizoram Mi leh Sa, Mizoram Pautna Tangkhangte lo Hana Dan Tttr Kaihhtttaina Siamthoit (Reaised Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) For Return of Permanent Residents of Mizorcrm Stranded Outside the State due to Couid-79 Lockdourin)" chu heta thiltel ang hian siamthat a ni a, hemi chungchanga hmalatute zawm atan tihchhuah a ni e. sd/-LALBIAKSANGI Secretary to the Govt. of Mizoram Disaster Management & Rehabilitation Department Memo No.B.73O27flO5/2O2O-DMR : Aizaul, the 75th of Mag, 2O2O Copy to: 1. P.S. to Chief Minister,Mizoram for information. 2. P.S. to Deputy Chief Minister, Mizoram 3. P.S. to Speaker, Mtzorasrt 4. P.S. to all Ministers/Ministers of State/Deputy Speaker/Vice- Chairman/Deputy Govt. Chief Whip, Mizorarn. 5. Sr. P.P.S to Chief Secretary, Govt. of Mtzora.m. 6. P.P.S. to Addl. Chief Secretary to Chief Minister, Govt. of M2oram. 7. A11 Principal Secretaries/ Commissioner/ Secretaries/ Special Secretaries, Govt. of Mworam. 8. Director General of Police, Mizotam 9. Administrative Heads of Departments, Government of Mizoram Secretary of all Constitutional & Statutory Bodies , Mtzotam. 10. Chairpersons, Task Group on Medicine & Medical Equipments/ Quarantine Facilities/Commodities & Transp ort / Migrant Workers & Stranded Travellers/ Media & Pr.rblicity/ Documentation. 1 1. A11 Deputy Commissioners, Mizoram. 12. A11 Superintendents of Police, Mworam. 13. Director, I&PR for wide publicity. -

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1 Vol. V No. 2 April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES Vol. V No. 2 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) April - June, 2016 Editorial Board of Mizo Studies w.e.f April 2016.... Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Editor - Prof. R.Thangvunga Circulation Managers - Mr. Lalsangzuala - Mr. K. Lalnunhlima © Deptt. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal will not entertain any legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies April - June 2016 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Team Work - 5 English Section 1. Joseph C. Lalremruata Evolution of party Politics in Mizoram: A Study of the First Political Party - Mizo Union - 7 2. R. Thangvunga Magic and Witchcraft in Mizo Folklore - 17 3. Laltluangliana Khiangte Powerful Tones of Women in Mizo Folksongs - 23 Mizo Section 1. Darchuailova Renthlei Mizo |awng thl<k chhinchhiahna (Tone Markers)- 29 2. V. Lalberkhawpuimawia Thih hnu piah lam Pipute Suangtuahna Khawvel - 47 3. Denish Lalmalsawma Mizo Hlaa Poetic Technique kan hmuh \henkhatte- 71 4. -

Issues of Governor and Article 356 in Mizoram

Vol. VI, Issue 1 (June 2020) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Issues of Governor and Article 356 in Mizoram Lalrinngheta * Abstract In this article an attempt is made to study how the role of Governor is important in centre-state relations in India, pariticularly in the case of Mizoram. Its implications on the state especially when regime changes at the centre. Imposition of Article 356 thrice in the state of Mizoram and political background on which they were imposed were studied. Keywords : Governor, Article 356, Mizoram, Centre-State Relations. Mizoram was granted Union Territory only in 1972. From this time onwards till it attained statehood in 1987 there are six Lieutenant Governors in the U. T. After it attained statehood there are 18 Governors in the state till today (the incumbent one Kummanam Rajasekharan in 2018). These sixteen Governors of Mizoram were distinguished figures in their career and professions. Their professions vary from army personnel, politicians, bureaucrats, lawyers and agriculturist to academician.1 During the period 2014-2016 Mizoram had seven Governors. There has even been a feeling among the Mizo people that the Central Government was playing a dirty game with regard to the appointment of Governor in the state. The Mizo Zirlai Pawl (the largest student’s body in the state) also stated that the state deserved better treatment not just like where disfavoured Governors were posted. When BJP under the alliance of NDA formed government at the centre in 2014 turmoil had begun in the post of Governor of Mizoram. The first case being Vakkom B. Purushothaman. He was appointed as the 18 th Governor of Mizoram on 26 th August 2011 by President Pratibha Patil by replacing Madan Mohan Lakhera and took office on 2 nd September 2011 during Indian National Congress ruled at the centre. -

(14.3.9S) 1 - ,10 ,, I/':; 2Nd Sitting (1S.3.9S) 11 - 94

,, lAWN AWLNA, ( INDEX J f_.: ,Pagelf ~"t 1. 1st Sitting (14.3.9S) 1 - ,10 ,, i/':; 2nd sitting (1S.3.9S) 11 - 94 . 3,_ . • 3rd Sittin,9 (16.3.9S) 9S ..... , 96: 4. 4th· Sitting (20.3.9S) 97 167 , 4'- ,'<i' S. Sth Sitting (21.3.90) 168,lj 234 6. 6.th Sitting (22.3.9S) 23S~" 3J7 -7. 7th Sitting (23.3.9S) 338 ... 418 9, '8th Sitting (24.3.9s) 419- ,497 • ~~h Sitting (27.3.9S) 49 8": ,577 10. 10th Sitting ·(2B.3.9S) 57B- ,67~ 11 • t1th. SittftH3 (29.3.9S) 680- ~9 "VO-. 12. 12th 5.i ttin-g' (30.3.9,5) 800. 'B72 -:, , 13. 13th Sitting , (31.3.9S) 873- " 941 ..,., 14. 14th Sitting ( 3.4.95) 942'-', 1992 • .'. - • No. MAL. 33/95/3 .o ~~ted A±z-awi, '-the 20th .sept, ,'5. '- -- TO, PU _~__-"- ~ • SUbject. .o proceedings --oi Mizoram- Legi;slativ-~ Assembly (Mizb .ver s.t on) - .auppLy. of .. Sir, I ~m directed to forward herewith a copy of Mizo ver-at.on of the Fifth sceai.on of the Third Mizoram '. State Legislative Assembly' Proceedings fqr ;favour of your information and record. Kindly acknowledge receipt of the same. " Yours faithfully, ;L...-tV-t0 (jL,Y.-;C~Cl ( SA",:>CHHUNGA) \( \ I Undersecretary. Mizoram"L'e...,9islative, Assembly. V-.-r-.1'1. .- ~ Memo No. MAL. 33/95/3 o. Da-te9- AizBwl; the 20th sept. Copy to :- -1) secretary General, Rajy.a' Sabha secree arf at, New Delhi. • 2) secretary General; Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi. ' - 3) p • S. -

Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan Serchhip District

SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN SERCHHIP DISTRICT DISTRICT ELEMETARY EDlfCATION PLAN SERCHHIP DISTRICT, MIZORAM Prepared by : District Unit of The SSA Mission, Serchhip District, Mizoram SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN DISTRICT El.EM El ARY EDUCATION PLAN SERCHHrP DISTRICT, MIZORAM Prepared by : District Unit of The SSA Mission, Serchhip District, Mizoram J a MAP OF SI fiC DISIHIC AIZAWL DISTRIC I V #Khumtung Hniawngkawn # # Baktawng •H iiaitu i •Buhkangkawn jj #Hmunth<-3 Chfiingchhip - . - . #Khawtjel. 'Vanchehgpui' U •ih en tlan g 5 H Rullam CD ^hhiahtlang Liinqpho Sialhau < X NuentiatigJue Cl 0 New Serchhip 9 < #Vanchengte X Neihloh % i hinglian O SERCHHIP HriangtTang Hmunzawl Thenzawl Buangpui Piler Khawlailung Chekawn I E. Lunadc I #Bu(igtlang Mualcheng* "X I eng# i3 Sialsir sta\jwktlang^ . Lungchhuan ^ Sailulak N. Vanlaiphai i ' l u n (; le I D isxm cT Luj^gkawlh g sru cu n ip DISl RICT AT A CLAI\(T- I Name olDistrirl Serclihip 2. Niiine ol hetidqiiaitcrs Serchhip V Areas 1372,61 Sq, Kin. (Approx ) I - Total I’opiilalioii S5539 ii)JJii)aii ()p()iil.ati.oij 29-206................................. (ii) Rural population 26333 5 I iteracy ))ercentage 96 1 7% 6. Density 0r|)0|)ula(J0n 47 per S(j Km. 7. No of villages/habitations 38 8 No of towns 3 9 (i) No. of Pnniaiy Sch()ols private) 98 (li) No. of Upper lYimaiy Schools {Incl. private) 68 (iii) No of liS’s (Including Private) 23 (iv)No. ofHSS’s 2 (v) No. of College 10. No. of Educational Clusters : 12 1 I. No. of Educational Circles 12. No of Bducalional Sub-Division 13, No of Rural Development IMocks 14 No of Civil Sub-Divisions INDKX C hapler Con(ents Page No. -

A Study in Aizawl Di

DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled Welfare Administration of the Aged in Mizoram: A Study in Aizawl District is the result of my own research work under the guidance and supervision of Dr Lalneihzovi, Associate Professor, Department of Public Administration, Mizoram University. I further declare that this dissertation or any part of it has not been submitted for any other degree or diploma course in the same university or elsewhere. (MARY LALNGAIHAWMI) Research Scholar Department of Public Administration Date: i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Lalneihzovi for her support, help and guidance in the course of my study. I would also like to thank the office bearers of Mizoram Upa Pawl for their help and information. I also thank my husband Lalsangzela Pachuau and daughter Adriana Lalbiakchami for bearing with me during the course of my study. I also thank the faculty members the Department of Public Administration for their suggestions. Above all, I thank the Lord for blessing me with health and wisdom in carrying out this research work. MARY LALNGAIHAWMI ii ABBREVIATIONS ADC : Autonomous District Council AMC : Aizawl Municipal Council BPL : Below Poverty Line CBHCE : Community Based Health Care for the Elderly CBI : Central Bank of India CDPO : Child Development Project Officer CSS : Centrally Sponsored Scheme DC : District Council DSWO : District Social Welfare Office/Officer FASC : Federation of Association of Senior Citizens GA : General Assembly GS : General Secretary IGNDPS -

“This Is Our Land” | Ethnic Violence and Internal Displacement in North-East India 5 Recommendations

India “This is our land” Ethnic violence and internal displacement in north-east India Acknowledgements IDMC would like to thank all those who provided invaluable support and information and reviewed this report. Cover photo: An internally displaced woman in a makeshift relief camp in Kukurkata in Goalpara district of Assam state near the Assam-Meghalaya border. (Photo: Ritu Raj Konwar, January 2011) Cover design by Laris(s)a Kuchina, laris-s-a.com Published by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre Norwegian Refugee Council Chemin de Balexert 7-9 CH-1219 Châtelaine (Geneva) Tel: +41 22 799 0700 / Fax: +41 22 799 0701 www.internal-displacement.org “This is our land” Ethnic violence and internal displacement in north-east India November 2011 Contents Executive summary 4 Recommendations 6 1 Introduction 9 2 Overview of the numbers of people internally displaced 11 3 Displacement in the Assam-Meghalaya border region 12 4 Displacement in Western Assam 15 5 Displacement from Mizoram to Tripura 21 6 Overview of national responses 25 Sources 26 Notes 29 About the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre 32 Executive summary The north-eastern region of India has seen many epi- in India Some data on IDPs in camps has been published sodes of armed conflict and generalised violence since by the authorities of districts hosting camps, but this India’s independence in 1947 Some of these situations information is usually not updated regularly When an caused massive internal displacement, of hundreds of IDP camp is closed, its residents may no longer