Telengana People's Struggle and Its Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile No PASARE SANDEEP (71286) TELANGANA (Adilabad)

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile no PASARE SANDEEP (71286) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Indravelli - Narnoor) 8333058240 KUMBOJI VENKATESH (73448) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Adilabad Rural - Adilkabad) 9652885810 ANNELA ANIL KUMAR (71285) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Boath - Mavala) 9989298564 CHOUDHARY PARASHURAM (64601) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Bhela - Jainath) 8500151773 KOLA NAGESH (64600) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Neradigonda - Gudihathnoor) 6305633892 RAMAGIRI SAI CHARAN (64598) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Bajarhathnoor - Utnoor) 9000669687 SUNKA RAMULU (64488) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Talamadugu) 9676479656 THUKKAREDDY RAJENDHAR TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Ichoda - Srikonda) 7993779502 REDDY (64487) BOJANAM VANITHA (64258) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Adilabad Rural - Adilkabad) 8333958398 KOKKULA MALLIKARJUN (61007) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Adilabad Rural - Adilkabad) 9640155109 ARGULA JAIPAL (72523) TELANGANA (Adilabad) (Adilabad Rural - Adilkabad) 8500465732 JANA RAJASRI (63026) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Velpoor - Bheemgal) 8897974188 BENDU NAVEEN (70971) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Mendora - Erragatla) 6305672227 RAJASHEKAR ENUGANTI (63088) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Armoor - Jakaranpally) 9059848340 BHUCHHALI SAI PRIYA (68731) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Nizamabad North South) 9177234014 PALTHYA PREMDAS (71113) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Rudrur - Varni - Kotagiri) 8121557589 M SAI BABU (63018) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Indalwai - Dichpally) 9989021890 GUNDLA RANJITH KUMAR (61437) TELANGANA (Nizamabad) (Sirikonda - Dharpally) 8500663134 BOTHAMALA NARESH (63035) TELANGANA -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

2019071371.Pdf

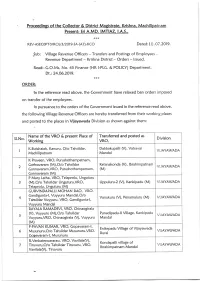

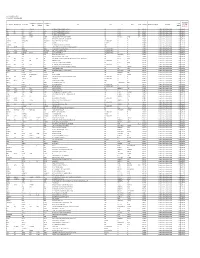

.:€ ' Proceedings of the Collector & District Magistrate. Krishna, Machilipatnam Present: Sri A.MD. lMTlAZ, 1.A.5.. >kJ.* REV-A5ECoPT(VRO)/3 /2o1s-sA-(A7)-KCo Dated: l0 .07.2019. Sub: Village Revenue Officers - Transfers and Postings of Employees - Revenue Department - Krishna District - Orders - lssued. Read:- 6.O.Ms, No. 45 Finance (HR l-P16. & POLICY) Department, Dt.:24.06.2019. ,( :k )k ORDER: {n the reference read above, the Government have relaxed ban orders imposed on transfer of the employees. ln pursuance to the orders of the Government issued in the reference read above, the following Village Revenue Officers are hereby transferred from their working places and posted to the places in Vijayawada Division as shown against them: :' Name of the VRO & present Place of Transferred and posted as 5l.No. Division Working VRO, K.Butchaiah, Kanuru, O/o Tahsildar, Dabbakupalli (V), Vatsavai I VIJAYAWADA Machilipatnam Mandal K Praveen, VRO, Purushothampatnam, 6arlnavaram (M),O/o Tahsildar Ketanakonda (V), lbrahimpatnam 2 VIJAYAWADA Gannavaram,VRO, Purushothampatnam, (M) Gannavaram (M) P Mary Latha, VRO, Telaprolu, Unguturu 3 (M),O/o Tahsildar Unguturu,VRO, Uppuluru-2 (V), Kankipadu (M) VIJAYAWADA Telaprolu, Unguturu (M) GURVINDAPALLI MOHAN RAO, VRO, 6andigunta-1, Vuyyuru Mandal,O/o 4 Vanukuru (V), Penamaluru (M) VIJAYAWADA TaLxildar Vuyyuru, VRO, Gandigunta-1, Vuwuru Mandal RAYALA RAMADEVI, VRO, Chinaogirala (V), Vuyyuru (M),O/o Tahsildar Punadipadu-ll Village, Kankipadu 5 VIJAYAWADA Vuyyuru,VRO, Chinaogirala (V), Vuyyuru Mandal (M) P-PAVAN KUMAR, VRO, Gopavaram-|, Enikepadu Village of Vijayawada 6 Musunuru,O/o Tahsildar Musunuru,VRO, VIJAYAWADA Rural Gopavaram-|, Musunuru VRO, Vavi lala (V), R.Venkateswararao, Kondapallivillage of 7 Tiruvuru,O/o Tahsildar Tiruvuru, VRO, VIJAYAWADA lbrahimpatnam Mandal Vavilala(V), Tiruvuru M.fhantibabu, VRO, Pamidimukkala,O/o Northvalluru I of Thotlavalluru 8 Tahsildar Pamidimukkala.VRO. -

Reconstructing the Population History of the Largest Tribe of India: the Dravidian Speaking Gond

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498 & 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 1018-4813/17 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Reconstructing the population history of the largest tribe of India: the Dravidian speaking Gond Gyaneshwer Chaubey*,1, Rakesh Tamang2,3, Erwan Pennarun1,PavanDubey4,NirajRai5, Rakesh Kumar Upadhyay6, Rajendra Prasad Meena7, Jayanti R Patel4,GeorgevanDriem8, Kumarasamy Thangaraj5, Mait Metspalu1 and Richard Villems1,9 The Gond comprise the largest tribal group of India with a population exceeding 12 million. Linguistically, the Gond belong to the Gondi–Manda subgroup of the South Central branch of the Dravidian language family. Ethnographers, anthropologists and linguists entertain mutually incompatible hypotheses on their origin. Genetic studies of these people have thus far suffered from the low resolution of the genetic data or the limited number of samples. Therefore, to gain a more comprehensive view on ancient ancestry and genetic affinities of the Gond with the neighbouring populations speaking Indo-European, Dravidian and Austroasiatic languages, we have studied four geographically distinct groups of Gond using high-resolution data. All the Gond groups share a common ancestry with a certain degree of isolation and differentiation. Our allele frequency and haplotype-based analyses reveal that the Gond share substantial genetic ancestry with the Indian Austroasiatic (ie, Munda) groups, rather than with the other Dravidian groups to whom they are most closely related linguistically. European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.198; published online 1 February 2017 INTRODUCTION material cultures, as preserved in the archaeological record, were The linguistic landscape of India is composed of four major language comparatively less developed.10–12 The combination of the more families and a number of language isolates and is largely associated rudimentary technological level of development of the resident with non-overlapping geographical divisions. -

List of Para Legal Volunteers Pertaining to the Unit of the Chairman, District Legal Services Authority, Khammam

LIST OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS DISTRICT: KHAMMAM Sl.No. Name and Address of the Para Legal Volunteers Mobile/ Land line number, e-mail ID, if any, of Para Legal Volunteer 1 Khammam K.Revathi, W/o.Durga -- Prasad,H.No.8-8-277, Sukravaripet, Khammam 2 Khammam Alli Rajeswari, -- W/o.Ch.SrinivasaraoH.No.5-6- 108, B.Pakabanda Bazar, Khammam 3 Khammam Sk.Rahmathunnisa Begum, -- W/o.Kajamiya, H.No.8-6-186/A, Tummalagadda, Khammam 4 Khammam Ch.Venkataramana, -- W/o.RamaraoH.No.7-2-72, Ricob Bazar, Khammam 5 Khammam Sk.Hasana Bee, W/o.Sk.Zakir -- Hussain, H.No.8-7-1142, Sukravaripet, Khammam 6 Khammam Ch.Anjanamma, -- W/o.G.Krishna,LIGH.NO.13, Cheruvubazar, Khammam 7 Khammam K.P.Laxmikantha , W/o.Bhaskar -- Rao, H.No.5-1-259, Church Compound, Khammam 8 Khammam K.Madhurilath, -- W/o.Srinivasarao,H.No.8-7-101, Sukravaripet, Khammam 9 Khammam K.Hitabala, W/o.Narayan -- Singh,H.No.9-8-23, Kamanbazar, Khammam 10 Khammam K.Swetha,D/o.Adinarayana,H.No. -- 11-6-139/1, Nehrunagar, Khammam 11 Khammam Dasari Sreedevi,W/o.Narasimha -- Rao, H.No.11-6-139, Nehrunagar, Khammam 12 Khammam R.Nagalaxmi, -- W/o.Veerabhadram,H.No.11-6- 47/3, Nehrunagar, Sweeper Colony, Khammam 13 Khammam K.Latha, W/o.Late -- Srinivasarao,H.No.5-5-278/2, Parsibandam, Khammam 14 Khammam Meda Sunitha, -- W/o.M.Ravi,H.No.7-4-28, Madaribazar, Khammam 15 Khammam KellaShyamala, W/o.Ugendar -- Sinha,H.No.7-4-42, Medar Bazar, Khammam 16 Khammam P.Kranthi, C/o.Chittamma, -- Kattaigudem(V),Laxminagaram (Po), Dummugudem (M), Khammam dt. -

5.2Nd Interim Dividend

DHANUKA AGRITECH LIMITED:CIN:L24219DL1985PLC020126 DETAIL OF SHAREHOLDER WHO HAVE NOT CLAIMED THEIR 2ND INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2015-16 Father/Husband Middle Father/Husband Last Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Name Name Address Country State District Pincode Folio No./Client ID DP ID/Client ID Amount Transferred ASHOK KUMAR JAIN NA S/O SH DURGA PRASHAD JAIN HOUSE NO 142 KRISHNA MANDI HISSAR INDIA Haryana 125001 P0000004 1000 [HARYANA] ANJALI SINDHWANI KRISHAN LAL A-19/3 D.D.A.SFS SAKET NEW DELHI. INDIA Delhi 110017 P0000010 1000 ANJANEYULU KOPPARAPU K KRISHANAIAH 1/257 MAIN BAZAR RLY KODUR CUDDAPAHA DISTT A.P. INDIA Andhra Pradesh 516101 P0000016 1000 BHAGWAT SAHAI SAXENA SH LS SAXENA C-14 MEER AZAD LANE TYPE III QUATERS M. AZAD MEDICAL COLLEGE INDIA Delhi 110002 P0000019 200 CAMPUS NEW DELHI BALANAGI REEDYBHIMI REDDY RAMA KRISHNA REDDY 14/142 C UPSTAIRS KAMLA NAGAR DCM A P ROAD ANANTAPUR INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 P0000024 1000 BIMLESH KAUSHIK NARAIN DUTT KAUSHIK 264 DELHI ADMINISTRATION FALTS KARKAR DOOMA DELHI INDIA Delhi 110092 P0000025 2000 BABU KURIAN K VARUGHESE 18 P DIZ AREA SECTOR IV BHAGAT SINGH MARG CONNAUGHT PLACE NEW INDIA Delhi 110001 P0000028 1000 DELHI DURGA PRASADARAO POTHINA VENKATESHWAR RAO C/O SRI VENKATA PADMAVATHI FERT. STALL NO 10 PATTABHI MKT INDIA Andhra Pradesh 521001 P0000035 2000 MACHALI PATNAM KRISHNA DT DAYAKAR NAGABANDI NA NA H NO 6/69/A C/O GEETHA FERTILISERS MAIN RD PARKAL WARANGAL AP INDIA Andhra Pradesh 506164 P0000037 2000 GANDHI ANANTHULA RATTAIAH NA C/O BHUMATHA AGENCIES J P N ROAD WARANGAL A.P. -

New Microsoft Office Excel Worksheet.Xlsx

PATEL INTEGRATED LOGISTICS LIMITED Unclaimed Dividend for the financial year 2009-10 Proposed Date of Father/Husband First Father/Husband Father/Husband Last Amount Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number DP Id-Client Id-Account Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Middle Name Name transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) KASHATURI DEVI KEWALCHAND DEVI 120 ANAND CLOTH MARKET AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT 380002 FOLIOK50178 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 115.00 24-OCT-2017 REKHA DEVI SALECHA PUKHRAJ SALECHA 120 ANAND CLOTH MARKET AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT 380002 FOLIOR50384 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 115.00 24-OCT-2017 SEEMA ASHOK KUMAR ASHOK KUMAR 120 ANAND CLOTH MARKET AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT 380002 FOLIOS50290 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 115.00 24-OCT-2017 DAKSHA MODI JAYENDRA MODI PVT PLOT NO 603 1 LALITA KUNJ SECTOR 7 INDIA GUJARAT 382007 FOLIOD50020 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 115.00 24-OCT-2017 S G KALIAPPAN GURUSAMY KALIAPPAN 17 RAMA ARANGANNAL 1ST STREET NEW WASHERMEN PET INDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600081 FOLIOS03196 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 24-OCT-2017 AKBAR BEGUWALA BEGUWALA BNELD ALGAK AREA 6 ST 64 P B NO 2861 SAFAT 13029 KUWAIT KUWAIT NA NA FOLIOA00111 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 200.00 24-OCT-2017 AMERIPADATH SURYANARAYANAN SURYANARAYANAN AL FUTTAIM TARMAC PTELTD P O BOX 1811 DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES NA NA FOLIOA00115 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend -

State District City Address Type Telangana Adilabad

STATE DISTRICT CITY ADDRESS TYPE AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO2 H NO;9116 BESIDE SBH ATM TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE BELLAMPALLY MAIN RD BELLAMPALLY ADILABAD DT AP504251 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO H NO11227 TO 230 CHENNUR ROAD TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD MACHERIAL RAJIV RAHADARI ( HYDERABAD) BESIDE ANDHRA BANK OFFSITE ATM MANCHERIAL ADILABAD DISTRICT AP 504208 AXIS BANK ATM, D NO 1 1 46 4 10 COLLECTOR CHOWK MAIN ROAD TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE ADILABAD 504001 AXIS BANK ATM, H NO 8 36 RAMNAGAR CCC X ROAD NASPUR TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE MANCHERIAL ADILABAD TELANGANA 504302 AXIS BANK ATM, H NO 1 1 43 1 A 1 OPP RAITHUBAZAR BESIDE ICICI TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE ATM ADILABAD TELANGANA 504001 AXIS BANK ATM, UTKUR CROSS ROAD, MAIN ROAD, LUXEITPET, TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE ADILABAD 504215, TELANGANA AXIS BANK LTD HNO 4360/1011OPP BUS STAND N H NO7ADILABAD TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD ONSITE 504001 ANDHRA PRADESH AXIS BANK ATM NETAJI CHOWK HNO4360/10 11 OPP BUS STAND NH TELANGANA ADILABAD ADILABAD OFFSITE NO7 ADILABAD ANDHRA PRADESH AXIS BANK ATM, D NO 28 4 140/1 CALTEX BESIDE HDFC BANK TELANGANA ADILABAD BELLAMPALLE OFFSITE BELAMPALLY DIST ADILABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 504251 AXIS BANK ATM, H NO 11 136 DASNAPUR GRAM PANCHAYAT TELANGANA ADILABAD DASNAPUR MAVALA OPP TANISHA GARDEN FUNCTION HALL ADILABAD 504001 OFFSITE AP AXIS BANK ATM SHOP NO1 HNO 13243 HIGHWAY ROAD INSPECTION TELANGANA ADILABAD MANCHERIAL OFFSITE BUNGLOW MANCHERIAL ADILABAD DT AP 504208 AXIS BANK ATM PUSKUR RESTURANT PVT.LTD C/O SRI JAGANADHA TELANGANA -

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Professor Severin Borenstein Dr. Michael Milligan Professor Daniel M. Kammen Professor Meredith Fowlie Fall 2016 India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures Copyright 2016 by Ranjit Deshmukh 1 Abstract India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources University of California, Berkeley Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Decarbonizing its electricity sector through ambitious targets for wind and solar is India's major strategy for mitigating its rapidly growing carbon emissions. In this dissertation, I explore the economic, social, and environmental impacts of wind and solar generation on India's future low-carbon electricity system, and strategies to mitigate those impacts. In the first part, I apply the Multi-criteria Analysis for Planning Renewable Energy (MapRE) approach to identify and comprehensively value high-quality wind, solar photovoltaic, and concentrated solar power resources across India in order to support multi-criteria prioritiza- tion of development areas through planning processes. In the second part, I use high spatial and temporal resolution models to simulate operations of different electricity system futures for India. In analyzing India's 2022 system, I find that the targets of 100 GW solar and 60 GW wind set by the Government of India that are likely to generate 22% of total annual electricity, can be integrated with very small curtailment (approximately 1%). -

Telangana Government Notification Rabi 2017-18

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Agriculture and Cooperation Department – Pradhan Manthri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY)– Rabi 2017 -18 - Implementation of “Village as Insurance Unit Scheme” and “Mandal as Insurance Unit Scheme under PMFBY -Notification - Orders – Issued. AGRICULTURE & CO-OPERATION (Agri.II.) DEPARTMENT G.O.Rt.No. 1182 Dated: 01-11-2017 Read the following: 1. From the Joint Secretary to Govt. of India, Ministry of Agriculture, DAC, New Delhi Lr.No. 13015/03/2016-Credit-II, Dated.23.02.2016. 2. From the Commissioner of Agriculture, Telangana, Hyderabad Lr.No.Crop.Ins.(2)/175/2017,Dated:12-10-2017. -oOo- O R D E R: The following Notification shall be published in the Telangana State Gazette: N O T I F I C A T I O N The Government of Telangana hereby notify the Crops and Areas (District wise) to implement the “Village as Insurance Unit Scheme” with one predominant crop of each District and other crops under Mandal Insurance Unit scheme under Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY) during Rabi 2017 -18 season vide Annexure I to VIII and Annexure I and II and Statements 1-30 and Proforma A&B of 30 Districts for Village as Insurance Unit Statements 1 to 30 for Mandal Insurance Unit and Appended to this order. 2. Further, settlement of the claims “As per the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY) Guidelines and administrative approval of Government of India for Kharif 2016 season issued vide letter 13015/03/2016-Credit-II, Dated.23.02.2016 the condition that, the indemnity claims will be settled on the basis of yield data furnished by the State Government based on requisite number of Crop Cutting Experiments (CCEs) under General Crop Estimation Survey (GCES) conducted and not any other basis like Annavari / Paisawari Certificate / Declaration of drought / flood, Gazette Notification etc., by any other Department / Authority.