The London Borough of LEWISHAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Borough of Lewisham Catford Retail and Economic Impact Assessment Final Report for Consultation

Peter Brett Associates LLP 16 Brewhouse Yard London EC1V 4LJ t: 020 7566 8600 London Borough of Lewisham Catford Retail and Economic Impact Assessment Final Report for Consultation Final Report for Consultation January 2013 Peter Brett Associates LLP disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of this report. This report has been prepared with reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the Client and generally in accordance with the appropriate ACE Agreement and taking account of the manpower, resources, investigations and testing devoted to it by agreement with the Client. This report is confidential to the Client and Peter Brett Associates LLP accepts no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report or any part thereof is made known. Any such party relies upon the report at their own risk. © Peter Brett Associates LLP 2013 Job Number 27149-001 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... i-iv 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 Terms of reference ................................................................................................................. 1 Challenges for Catford ........................................................................................................... 3 Structure of report ................................................................................................................. -

Deptford Church Street & Greenwich Pumping Station

DEPTFORD CHURCH STREET & GREENWICH PUMPING STATION ONLINE COMMUNITY LIAISON WORKING GROUP 13 July 2021 STAFF Chair: Mehboob Khan Tideway • Darren Kehoe, Project Manager Greenwich • Anil Dhillon, Project Manager Deptford • Natasha Rudat • Emily Black CVB – main works contractor • Audric Rivaud, Deptford Church Street Site Manager • Anna Fish– Deptford Church Street, Environmental Advisor • Robert Margariti-Smith, Greenwich, Tunnel & Site Manager • Rebecca Oyibo • Joe Selwood AGENDA Deptford Update • Works update • Looking ahead • Noise and vibration Greenwich Update • Works update • Looking ahead • Noise and vibration Community Investment Community Feedback / Questions DEPTFORD CHURCH STREET WHAT WE’RE BUILDING DEPTFORD WORKS UPDATE SHAFT & CULVERT Shaft • Vortex pipe installed and secondary lining complete • Tunnel Boring Machine crossing complete • Vortex generator works on-going Culvert • Excavation complete • Base slab and walls complete • Opening to shaft complete DEPTFORD WORKS UPDATE COMBINED SEWER OVERFLOW (CSO) CSO Phase 1: Interception Chamber • Internal walls and roof complete • Mechanical, Electrical, Instrumentation, Controls, Automation (MEICA) equipment installation on-going CSO Phase 2: Sewer connection • Protection works of Deptford Green Foul Sewer complete • Secant piling works complete • Capping beam and excavation to Deptford Storm Relief Sewer on-going time hours: Monday to Friday: 22:00 to 08:00 DEPTFORD 12 MONTHS LOOK AHEAD WHAT TO EXPECT AT DEPTFORD CSO: connection to existing sewer Mitigations • This work will take place over a 10 hour shift – the time of the shift • Method of works chosen to limit noise will be dependent on the tidal restrictions in the Deptford Storm Relief Sewer’ generation such as sawing concrete into • Lights to illuminate works and walkways after dark blocks easily transportable off site. -

Arch 133, Deptford Railway Station, London

Arch 133, Deptford Railway Station, London Location Rent Deptford in South East London has benefited from major investment £28,000 per annum exclusive. over the last few years and now has a thriving vibrant local community of creatives and professionals. Rates The listed arches are situated on the approach to Deptford Station, Rateable Value To be assessed. accessed via Deptford High Street. Rates Payable 2016/17 To be assessed. The arches share a market yard with The Deptford Project – a new mixed Interested parties are advised to make their own enquiries to Lewisham use scheme extending to 14 arches, 7 commercial units, 2 restaurants, 3 Council (020 8314 6000). town houses and 140 apartments. Specification Accommodation The arch will be handed over in shell condition with a new corrugated Ground Floor 1,038 sq ft 96.47 sq m lining and capped services – further details upon request. Total 1,038 sq ft 96.47 sq m Energy Performance Certificate To be assessed. Lease Term Costs Available on a new standard Network Rail leases – further details upon request. Each party is to be responsible for their own legal costs incurred in the transaction. Contact Tom Jamson +44 (0)20 7317 3722 [email protected] +44 (0)20 7317 3700 | www.klm-re.com Misrepresentation Act 1967 & Property Misdescription Act 1991. These Particulars are believed to be correct but their accuracy is not guaranteed, are set out as a general guide and do not constitute the whole or part of a contract. All liability, in negligence or otherwise, arising from the use of the particulars is hereby excluded. -

Working Together to Tackle Poverty in Lewisham

Working together to tackle poverty in Lewisham The final report of the Lewisham Poverty Commission October 2017 Contents Foreword 3 1. Introducing the Poverty Commission: a realistic but ambitious approach 4 The Commission 4 Focusing on poverty 4 The role of Lewisham Council in tackling poverty 5 Action at a local level 5 Working together to tackle poverty 5 2. Poverty in Lewisham 6 Lewisham and its people 6 The impacts of poverty 6 Quantifying poverty in Lewisham 8 The difficulties in getting well-paid, secure work 10 Children living in poverty 13 The price of unaffordable housing 14 The Commission’s focus 14 3. Supporting residents to access well-paid, secure jobs inside and outside of Lewisham 15 Works, skills and the role of anchor institutions 15 Recommendations 17 4. Tackling child poverty by supporting parents into decent work 20 Child poverty, child care and lone parent unemployment 20 Recommendations 21 5. Improving the local housing market 23 Housing in Lewisham 23 Recommendations 24 6. Strengthening support within communities 27 Increasing community resilience 27 Recommendations 29 7. Working together to tackle poverty: next steps and implementation 31 An immediate response 31 Change across the community 31 Advising national government 31 Staying the course 31 Appendix 1: Listening to Lewisham’s people and its organisations 32 Our approach to consultation and engagement 32 Further data and evidence 33 Summary of comments received from residents 34 2 Foreword Lewisham is a great place to live, with a strong and diverse community. Yet, despite being situated in the heart of London, on the doorsteps of one of the wealthiest cities in the world, tens of thousands of Lewisham residents live in poverty. -

Regeneration in Deptford, London

Regeneration in Deptford, London September 2008 Produced by Dr. Gareth Potts BURA Director of Research, Policy and Best Practice Contact: 07792 817156 Table of Contents Planning and Regeneration Strategy ......................................................................................................................... 3 Early Community Regeneration .............................................................................................................................. 11 Renewal of the Pepys Estate .................................................................................................................................... 15 Riverside Schemes ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 Inland Development ................................................................................................................................................... 24 Deptford Town Centre Regeneration Programme ............................................................................................ 33 Some Novel Approaches to Regeneration ........................................................................................................... 36 Appendices .................................................................................................................................................................. 38 Planning and Regeneration Strategy The Planning Framework The key planning guidelines are set out in the -

Lewisham Labour 2018 Manifesto

LEWISHAM FOR THE MANY NOT THE FEW MANIFESTO 2018 Lewisham for the many, not the few Lewisham Labour’s Manifesto for the 2018 Local Elections 2 Inside 07 Damien Egan – Building a Lewisham for the many 11 Open Lewisham 15 Tackling the Tory housing crisis 19 Giving children and young people the best start in life 23 Building an economy for the many 27 Protecting our NHS and social care 31 Making Lewisham greener 35 Tackling crime 39 Your Lewisham Labour candidates 50 Get involved Pictured left, Lewisham Labour members’ manifesto workshops Damien Egan — Building a Lewisham for the many Welcome to Lewisham Labour’s Manifesto for the next four years, on which I as Mayoral candidate and 54 councillor candidates are standing on May 3rd: a platform that offers a bold, radical, socialist alternative. The elections give us the opportunity to show exactly what our community thinks of the Tory and Lib Dem Coalition Government’s massive cuts and how their austerity agenda has failed the country. We are in a fight to protect services for vulnerable residents on a scale like we have never seen before. This Manifesto highlights the many things that, together, we can do, while highlighting how much more we could do with a Labour government. It outlines what we want to do to make life better for everyone in Lewisham. That’s why it’s a huge honour to be selected by Labour’s membership as their candidate for Mayor of Lewisham. I love this borough and am proud to have served it as a councillor for the last eight years. -

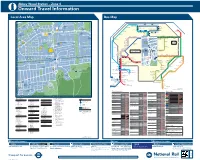

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 45 1 HARTSLOCK DRIVE TICKFORD CLOSE Y 1 GROVEBURY ROAD OAD 16 A ALK 25 River Thames 59 W AMPLEFORTH R AMPLEFORTH ROAD 16 Southmere Central Way S T. K A Crossway R 1 B I N S E Y W STANBROOK ROAD TAVY BRIDGE Linton Mead Primary School Hoveton Road O Village A B B E Y W 12 Footbridge T H E R I N E S N SEACOURT ROAD M E R E R O A D M I C H A E L’ S CLOSE A S T. AY ST. MARTINS CLOSE 1 127 SEWELL ROAD 1 15 Abbey 177 229 401 B11 MOUNTJOYCLOSE M Southmere Wood Park ROAD Steps Pumping GrGroroovoveburyryy RRoaadd Willow Bank Thamesmead Primary School Crossway Station W 1 Town Centre River Thames PANFIE 15 Central Way ANDW Nickelby Close 165 ST. HELENS ROAD CLO 113 O 99 18 Watersmeet Place 51 S ELL D R I V E Bentham Road E GODSTOW ROAD R S O U T H M E R E L D R O A 140 100 Crossway R Gallions Reach Health Centre 1 25 48 Emmanuel Baptist Manordene Road 79 STANBROOK ROAD 111 Abbey Wood A D Surgery 33 Church Bentham Road THAMESMEAD H Lakeside Crossway 165 1 Health Centre Footbridge Hawksmoor School 180 20 Lister Walk Abbey Y GODSTOW ROAD Footbridge N1 Belvedere BUR AY Central Way Wood Park OVE GROVEBURY ROAD Footbridge Y A R N T O N W Y GR ROAD A Industrial Area 242 Footbridge R Grasshaven Way Y A R N T O N W AY N 149 8 T Bentham Road Thamesmead 38 O EYNSHAM DRIVE Games N Southwood Road Bentham Road Crossway Crossway Court 109 W Poplar Place Curlew Close PANFIELD ROAD Limestone A Carlyle Road 73 Pet Aid Centre W O LV E R C O T E R O A D Y 78 7 21 Community 36 Bentham Road -

South East London Green Chain Plus Area Framework in 2007, Substantial Progress Has Been Made in the Development of the Open Space Network in the Area

All South East London Green London Chain Plus Green Area Framework Grid 6 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 56 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA06 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA06 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www. london.gov.uk/publication/all-london-green-grid-spg . -

Planning Application Design & Access Statement Van-0387

PLANNING APPLICATION DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT VAN-0387 53 PERRY VALE, FOREST HILL, LONDON, SE23 2NE SEPTEMBER 2018 1.0 Contents VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 1.0 Contents 1 2.0 Introduction 2 3.0 Site analysis and Current Building 5 4.0 Description of the proposal 7 5.0 Use and Layout 10 6.0 Heritage Statement 12 7.0 Planning History and Policies 15 8.0 Architectural Character and Materials 15 9.0 Landscaping and Trees 19 10.0 Ecology 19 11.0 Extract, Ventilation and Services 20 12.0 Cycle Storage and Refuse 20 13.0 Sustainability and Renewable Energy Technology 21 14.0 Access & Mobility Statement 21 15.0 Transport, Traffic and parking Statement 22 16.0 Acoustics 22 17.0 Flood Risk 22 18.0 Statement of Community Engagement 23 19.0 Conclusion 24 1 2.0 Introduction VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 This application submission is prepared by db architects on behalf of Vanquish Iconic Developments for the site at 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE. Vanquish are a family-run business and have been creating urban industrial interior designed developments for many years now across South East London. "We are a firm believer that property development should be creative, not made with basic materials to fit the standard criteria of a build. This is reflected in our interiors and exteriors of each finished development. -

Assessment of Current and Future Cruise Ship Requirements in London

London Development Agency June 2009 AN ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT AND FUTURE CRUISE SHIP REQUIREMENTS IN LONDON In conjunction with: 5 Market Yard Mews 194 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3TQ Tel: 020 7642 5111 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Current cruise facilities in central London 4 3. The organisational and planning context 8 4. The cruise market and future demand 11 5. Views of cruise operators 19 6. Potential for growing cruise calls to London 22 7. Assessment of potential sites 24 8. Lessons from elsewhere 37 9. Conclusions 51 Appendices: Appendix 1: List of consultees Appendix 2: Seatrade cruise market report Appendix 3: Location plan of potential sites Appendix 4: Economic impact study Appendix 5: Overview of costs The Tourism Company – Assessment of current and future cruise ship requirements 2 1. INTRODUCTION This report was commissioned by the London Development Agency (LDA) and Greater London Authority (GLA), with support from the Port of London Authority (PLA) in response to a need for a better understanding of London’s future cruise facility requirements. This need is identified in the London Tourism Vision for 2006-2016, and associated Action Plan 2006-2009, under the theme ‘A Sustainable and Inclusive City’, one of whose objectives is to ‘Increase the profile and usage of services along the Thames’. London currently hosts a relatively small number of cruise ships each year, making use of the informal and basic mooring and passenger facilities at Tower Bridge and Greenwich. The aim of this research is to assess the extent to which the lack of a dedicated, more efficient cruise facility is discouraging operators from bringing cruise ships to London, and if there is latent demand, how might this be accommodated. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON THE BOUNDARIES OF THE LONDON BOROUGHS OF BROMLEY, CROYDON, LAMBETH, LEWISHAM, AND SOUTHWARK IN THE VICINITY OF CRYSTAL PALACE. REPORT NO. 632 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 632 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN SIR GEOFFREY ELLERTON CMG MBE MEMBERS MR K F J ENNALS CB MR G R PRENTICE MRS H R V SARKANY MR C W SMITH PROFESSOR K YOUNG SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON THE BOUNDARIES OF THE LONDON BOROUGHS OF BROMLEY, CROYDON, LAMBETH, LEWI SHAM AND SODTHWARK IN THE VICINITY OF CRYSTAL PALACE COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT AND PROPOSALS INTRODUCTION 1. On 1 April 1987 we announced the start of the review of Greater London, the London Boroughs and the City of London, as part of the programme of reviews we are required to undertake by virtue of section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. We wrote to each of the local authorities concerned. 2. Copies of our letter were sent to the appropriate county, district and parish councils bordering Greater London; the local authority associations; Members of Parliament with constituency interests; and the headquarters of the main political parties. In addition, copies were sent to the Metropolitan Police and to those government departments, regional health authorities, electricity, gas and water undertakings which might have an interest, as well as local television and radio stations serving the Greater London area and to a number of other interested persons and organisations. -

2018 Warden's Annual Public Engagement Awards Programme

Warden’s Annual Public Engagement Awards 2018 Celebrating excellence in public engagement at Goldsmiths 3 May 2018 Table of Contents 2 Welcome 3 Running Order 4 Established Researcher category 4 Winners 8 Commendations 10 Nominated 12 Early Career Researcher category 12 Winner 14 Commendation 15 Nominated 20 Postgraduate Researcher category 20 Winner 22 Commendation 24 Nominated Table of Contents — 1 Welcome Running order Welcome to the Warden’s Annual Public Engagement Awards ceremony at Warden’s Annual Public Engagement Awards Ceremony Goldsmiths, University of London. These awards recognise and celebrate the Richard Hoggart Building, Room 137 excellent work researchers at all career stages do with members of the public, whether they’re sharing ground-breaking findings with new audiences or 5pm Welcome by Pat Loughrey, Warden of Goldsmiths collaborating with the public throughout their research. 5.05pm Introduction by Dr John Price, Academic Lead for Public Engagement An exceptional range of innovative activities and projects were nominated by Goldsmiths staff, showcasing different approaches to engaging the public with 5.15pm The presentation of the awards and commendations in the category of research and practice. Our researchers worked with organisations like the BFI, the Established Researcher Labour Party, the Zoological Museum Hamburg and Parliament to engage diverse audiences through film, performance, art and citizen science. Two special awards for public engagement with an emphasis on community engagement and research impact will be also be presented. There was a real sense that researchers, partners and the public benefited from this work, demonstrating how research in the arts, humanities, social 5.35pm The presentation of the award and commendation in the category of sciences and computing can create positive change in the world.