2012 Palms Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents

Existing Conditions Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents Introduction Housing LOCATION .......................................................... 5 HOUSING STOCK ................................................ 29 EXISTING PL ANS AND STUDIES ............................... 12 HOUSING TYpeS ................................................. 30 Land Use & Mobility AGE ................................................................ 30 EleMENTS OF THE DISTRICT ................................... 13 Crime LAND USE/PROpeRTY CL ASSIFICATION ..................... 13 Economic Indicators ROADWAYS ........................................................ 16 BUSINESS SUMMARY ............................................ 35 TRAFFIC VOLUMES ............................................... 16 RETAIL TRADE .................................................... 38 RAILROAD ......................................................... 17 DAY TIME POPUL ATION .......................................... 40 BIKEWAYS ......................................................... 17 Planned Infrastructure Improvements RAILS TO TRAILS ................................................. 17 CAPITAL IMPROveMENTS ....................................... 45 PARKS & TRAILS ................................................. 21 RebUILD HOUSTON +5 ........................................ 45 REIMAGINE METRO ............................................. 21 Observations People OBSERVATIONS ................................................... 49 -

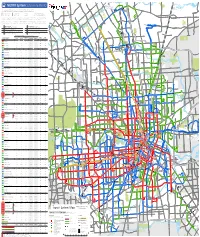

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Winter-Spring 1994

28 C i t e 3 I 1 9 9 4 The mall before the roof was added in 1966. Gulf gain, view from loop 610 oaQtfga^ The BRUCE C. W E B B C i t e 3 1 : 1 9 9 4 29 Gulf gale in ihe lot e 1950s. HI-; PROJK.T of relocating vintage center - Houston's first regional America's urban life into shopping center, located at Houston's entirely new, free-floating sub- first freeway interchange - was designed urban forms, begun after and built before the ubiquitous mall for TWorld War II, was accomplished in such mula had been fully developed and codi- short order and is now so pervasive that it fied. Gulfgate defies expectation by being is difficult to see it as a process at all. lopsidedly organized: its two anchor stores, Sakowitz (emptied out when the Particularly in a city such as Houston, 1 whose character was established along the Sakowitz chain folded in the early eight- lines of a suburban model, growth has ies) and Joske's (now Dillard's) were become synonymous with sprawl, and the located side by side at one end of the Gulfgate: view from the southeast showing entrance to underground servke tunnel an right. automobile orientation is so deeply woven center, whereas the usual plan forms the into the spatial fabric that even coherent mall into a dumbbell, with the two high- remnants of the city past, when they are volume "magnet" stores at either end of preserved at all, are splintered and frag- an inside street. -

Rider Guide / Guía De Pasajeros

Updated 02/10/2019 Rider Guide / Guía de Pasajeros Stations / Estaciones Stations / Estaciones Northline Transit Center/HCC Theater District Melbourne/North Lindale Central Station Capitol Lindale Park Central Station Rusk Cavalcade Convention District Moody Park EaDo/Stadium Fulton/North Central Coffee Plant/Second Ward Quitman/Near Northside Lockwood/Eastwood Burnett Transit Center/Casa De Amigos Altic/Howard Hughes UH Downtown Cesar Chavez/67th St Preston Magnolia Park Transit Center Central Station Main l Transfer to Green or Purple Rail Lines (see map) Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Westbound – Central Station Capitol Eastbound – Central Station Rusk Eastbound Theater District to Magnolia Park Hacia el este Magnolia Park Main Street Square Bell Westbound Magnolia Park to Theater District Downtown Transit Center Hacia el oeste Theater District McGowen Ensemble/HCC Wheeler Transit Center Museum District Hermann Park/Rice U Stations / Estaciones Memorial Hermann Hospital/Houston Zoo Theater District Dryden/TMC Central Station Capitol TMC Transit Center Central Station Rusk Smith Lands Convention District Stadium Park/Astrodome EaDo/Stadium Fannin South Leeland/Third Ward Elgin/Third Ward Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales TSU/UH Athletics District Northbound Fannin South to Northline/HCC UH South/University Oaks Hacia el norte Northline/HCC MacGregor Park/Martin Luther King, Jr. Southbound Northline/HCC to Fannin South Palm Center Transit Center Hacia el sur Fannin South Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Eastbound Theater District to Palm Center TC Hacia el este Palm Center Transit Center Westbound Palm Center TC to Theater District Hacia el oeste Theater District The Fare/Pasaje / Local Make Your Ride on METRORail Viaje en METRORail Rápido y Fare Type Full Fare* Discounted** Transfer*** Fast and Easy Fácil Tipo de Pasaje Pasaje Completo* Descontado** Transbordo*** 1. -

Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Department Planning and Development LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: James L. Autry House AGENDA ITEM: IV.d OWNERS: W. Murray Air and Mary B. Air HPO FILE NO: 09L217 APPLICANTS: Same DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-26-09 LOCATION: 5 Courtlandt Place – Courtlandt Place Historic District HAHC HEARING: May-21-09 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING: May-28-09 SITE INFORMATION The East 50 feet of Lot 23 and West 75 feet of Lot 24, Courtlandt Place subdivision, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a wood-frame and brick two-story residence. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The James L. Autry House was designed by Sanguinet and Staats in 1912. It is an excellent example of Neo-Classical Revival architecture and reflects the elegance and architectural quality common along Courtlandt Place, one of Houston's earliest and most exclusive subdivisions. Established in 1906, Courtlandt Place, a tree-lined, divided boulevard, has maintained its residential integrity despite surrounding commercialism in adjacent blocks, and is designated as both a City of Houston and National Register historic district. James Lockhart Autry was a significant figure in the early days of the Texas oil industry. As an attorney and judge, Autry was a pioneer in the field of oil and gas law. After the discovery of the Spindletop oil field in 1901, Autry helped Joseph Cullinan organize the Texas Fuel Company, now known as Texaco. In partnership with Cullinan and Will Hogg, Autry later formed several other oil companies. -

SWUTC/15/600451-00048-1 Proposing Transportation Designs

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No 3. Recipient's Catalog No SWUTC/15/600451-00048-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Proposing Transportation Designs and Concepts to Make Houston December 2015 METRO’s Southeast Line at the Palm Center Area more Walkable, 6. Performing Organization Code Bikeable, and Livable 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Khosro Godazi, Latissha Clark, and Vincent Hassell 600451-00048-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Transportation Training and Research Texas Southern University 11. Contract or Grant No. 3100 Cleburne DTRT12-G-UTC06 Houston, Texas 77004 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Southwest Region University Transportation Center Texas A&M Transportation Institute Texas A&M University System 14. Sponsoring Agency Code College Station, Texas 77843-3135 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program. 16. Abstract Over the years, the Palm Center (PC) in Houston, Texas, has been the beneficiary of several economic development endeavors designed to ignite economic and community growth and revitalization. While these endeavors brought forth initial success, they have failed to transform the PC into a lasting model of economic growth and prosperity and to inspire community pride and engagement. The development of METRO’s Southeast Line light rail station at the Palm Center Transit Center presents the prime opportunity for meeting the needs of the community by implementing design concepts and principles that provide social, environmental, and economic benefits to those living within close proximity of the transit station. -

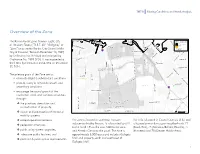

Overview of the Zone

TIRZ 8 Existing Conditions and Needs Analysis Overview of the Zone L TIRZ 7: O.S.T./ALMEDA BROADWAY ST OLD SPANISH TR Gulfgate Center ALLEN GENOA RD W HARRIS AVE The Reinvestment Zone Number Eight, City GRIGGS RD TIRZ 8: GULFGATE TIRZ 8: GULFGATE TIRZ 6: EASTSIDE TIRZ 8 Boundary Expansion GALVESTON RD of Houston, Texas, (“T.I.R.Z. #8,” “Gulfgate,” or YELLOWSTONE BLVD Other TIRZ LONG DR Herman A. Barnett Stadium City Limit Shopping Mall “Zone”) was created by the City Council of the Golf Course 610 PARK PLACE BLVD City of Houston, Texas on December 10, 1997, PARK PLACE BLVD ALLENDALE RD Glenbrook by Ordinance No. 97-1524 and enlarged by SCOTT ST RICHEY ST DIXIE DR HOWARD DR BROADWAY ST QUEENS RD Ordinance No. 1999-0706. It was expanded a HOLMES RD CRESTMONT ST S RICHEY ST W IN third time by Ordinance 2014-1192 on December K LER DR TELEPHONE RD 17, 2014. CULLEN BLVD HOUSTON BLVD SPENCER HWY BELLFORT ST S DRWAYSIDE JUTLAND RD The primary goals of the Zone are to: MYKAWA RD REED RD COLLEGE AVE G CITY OF HOUSTON A • eliminate blight & substandard conditions L V E S T O AIRPORT BLVD N R D • provide a way to remediate unsafe and MONROE RD OK DR EBRO Hobby Airport G ED unsanitary conditions 45 • SOUTH ACRES DR encourage the sound growth of the MARTINDALE RD residential, retail, and commercial sectors T SCOTT ST S R E AV D SH through: CLEARWOOD DR ALMEDA GENOA R S OREM RD E RDVILLE RD ALMEDA GENOA RD Almeda Mall the purchase, demolition and SCOTT ST OREM DR OREM DR WILLA reconstruction of property, ALMEDA GENOA RD Aerial Imagery, USDA NAIP 2014 ALLISON RD City Park Boundary, 2013 0 0.5 Miles Hawes Hill Calderon | www.hhcllp.com Aerial View, 2006 8/31/2015 INGSPOINT RD design and construction of improved K mobility systems, streetscape enhancements, The zone is located in southeast Houston The TIRZ is located in Council Districts D & I and pedestrian amenities, adjacent to Hobby Airport. -

Harry Clay Hanszen Ca.1950

Bibliography Primary Sources: The City of Houston. Timeline of Harry Clay Hanszen ca.1950. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. Hanszen, Alice. Alice Hanszen to J. T. McCants, April 5, 1955. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * Harry C. Hanszen Next of Kin. ca.1950. Document. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. Harry Clay Hanszen ca.1950. Document. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. The Houston Chronicles. “H.C. Hanszen Chosen To Head Of Rice Board.” January 15, 1946. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * The Houston Chronicle. “Harry C. Hanszen, Houston Oilman, Dies in Kerrville”, 1950, "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. * The Houston Chronicle. “Harry C. Hanszen Named Trustee by Rice Institute”, May 7, 1942. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. The Houston Press. “Harry C. Hanszen Elected As Chairman Of Rice Board.” January 15, 1946. "Hanszen, Harry C.”, Rice University Information File Records 1910-2017, UA361, vertical file, Folder H, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. -

Seagate Crystal Reports

HOUSTON PLANNING COMMISSION AGENDA NOVEMBER 20, 2008 CITY COUNCIL CHAMBER CITY HALL ANNEX 2:30 P.M. PLANNING COMMISSION MEMBERS Carol Lewis, Ph. D., Chair Mark A. Kilkenny, Vice Chair John W. H. Chiang David Collins Kay Crooker Sonny Garza James R. Jard D. Fred Martinez Robin Reed Richard A. Rice David Robinson Jeff Ross Lee Schlanger Algenita Scott Segars Talmadge Sharp, Sr. Jon Strange Beth Wolff Shaukat Zakaria The Honorable Grady Prestage, P. E., Fort Bend County The Honorable Ed Emmett, Harris County The Honorable Ed Chance, Montgomery County ALTERNATE MEMBERS D. Jesse Hegemier, P. E., Fort Bend County Mark J. Mooney, P. E., Montgomery County Jackie L. Freeman, P. E., Harris County EXOFFICIO MEMBERS M. Marvin Katz Mike Marcotte, P.E. Dawn Ullrich Frank Wilson SECRETARY Marlene L. Gafrick Meeting Policies and Regulations that an issue has been sufficiently discussed and additional speakers are repetitive. Order of Agenda 11. The Commission reserves the right to stop Planning Commission may alter the order of the speakers who are unruly or abusive. agenda to consider variances first, followed by replats requiring a public hearing second and consent agenda Limitations on the Authority of the Planning last. Any contested consent item will be moved to the Commission end of the agenda. By law, the Commission is required to approve Public Participation subdivision and development plats that meet the requirements of Chapter 42 of the Code of Ordinances The public is encouraged to take an active interest in of the City of Houston. The Commission cannot matters that come before the Planning Commission. -

Newsfromfondren

Volume 17, Number 1 Fall 2007 NEWS from FONDREN A LIBRARY NEWSLETTER TO THE RICE UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY Historic Treasures Emerge from Gym Daniel Webster once said, “What and brittle with age, had been stored is valuable is not new…” (Speech in the original field house and moved at Marshfield, Sept. 1, 1848). In the to the new gymnasium around 1950. Woodson Research Center, we are The locations of the discoveries, learning afresh the truth of that state- under the bleachers and in obscure ment as Rice’s rich historical record rooms at the very top of Autry in athletics slowly emerges through Court, suggest a reluctance to throw old, dirty, dusty, oftimes crumbling anything away. One room was above materials recently found in the the restrooms in the stadium, acces- recesses of the gymnasium. sible only by ladder. It took a lot of As renovation plans for the effort to get those boxes into such an athletic facility were finalized, staff out-of-the-way place. Artifacts found realized the need to retain valuable in various offices were likely kept for materials documenting Rice’s athlet- sentimental value or artistic form — ics programs through the years. Uni- trophies dating to 1915, a stuffed owl, versity historian Melissa Kean and a Rice owl decanter. university archivist Lee Pecht devised Responsibility for retaining and implemented a plan to transfer as written records mandated that certain many of the “finds” as possible to the files about sports programs be kept. Woodson Research Center. While However, over time staff retired or Dr. Kean conferred with athletics left Rice, records were inherited and staff to determine priorities and then interrelated files became separated. -

BRAZORIA COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM Collections Reflect the Musical and Cultural Development of Houston Through Departmental

ABOUT ARCHIVISTS OF THE HOUSTON AREA! THE AFRICAN AMERICAN LIBRARY AT THE GREGORY SCHOOL, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY HARRIS COUNTY ARCHIVES HOUSTON GRAND OPERA ARCHIVES AND RESEARCH CENTER Archivists of the Houston Area (AHA!) was founded in 1998 by four local archivists to 1300 Victor Street, Freedmen’s Town, Houston, TX 77019 11525 Todd Street, Suite 300, Houston, TX 77055 510 Preston Street, Houston, TX 77002 facilitate interaction among area archivists and repositories. AHA! exists to increase 832/393-1440 http://www.thegregoryschool.org 713/274-9683 www.harriscountytx.gov/archives 713/228-0238 www.houstongrandopera.org/archives contact and communication among archivists and those working with records, to Monday-Thursday, 10am-6pm and Saturday, 10am-5pm By appointment only Monday-Friday, 9am-4:30pm, by appointment only provide opportunities for professional development, and to promote archival The collection documents the experience of African American residents, businesses, institutions The County Archives documents the history of the government and the citizens of Harris County The Archives maintains a large collection of material related to the history of the Houston Grand repositories and activities in the greater Houston, Texas area. It fulfills its mission by: and neighborhoods throughout Houston and the surrounding region. as revealed through the county records and donated materials. Opera. Conducting quarterly meetings with programs on archival topics BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE ARCHIVES HOUSTON METROPOLITAN RESEARCH CENTER, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY Planning and promoting Archives Month 713/798-4501 www.bcm.edu Julia Ideson Building, 500 McKinney St., Houston, TX 77002 Providing professional development classes Currently a closed archive. Please call for further information. -

REQUEST for QUALIFICATIONS Co-Developer for Palm Center BTC

REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS Co-Developer for Palm Center BTC Houston, Texas RFQ # 16-012 DUE DATE: October 11, 2016 4:00 P.M. C.S.T. Houston Business Development, Inc. 5330 Griggs Road Houston, Texas (713)845-2400 www.hbdi.org CONTENTS I. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 II. Definitions, Terms and Conditions .................................................................................7 III. General Information ...................................................................................................... 8 IV. Scope of Work ............................................................................................................. 15 V. Proposal Format and Content Requirements ............................................................. 18 VI. Evaluation Factors ....................................................................................................... 21 VII. Notice of Non-participation Form............................................................................... 23 VIII. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................... 24 2 I. INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction 1.1. Houston Business Development, Inc. (HBDi) is seeking a developer team to plan and co- develop parcels located within the southeast area of Houston, Texas (“the Site”). This area is currently owned by HBDi, and the developer will act as a partner with HBDi to create a sustainable,