Shaping the Eighteenth-Century Criminal Trial: a View from the Ryder Sources John H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guarani and Kaiowá Peoples' Human Right to Adequate Food And

THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION NUTRITION FOOD AND ADEQUATE HUMAN RIGHTTO AND KAIOWÁPEOPLES’ THE GUARANI A A HOLISTIC APPROACH THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION A HOLISTIC APPROACH | Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive MISSIONARY COUNCIL FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION A HOLISTIC APPROACH | Executive Summary Support: This Executive Summary is a publication of FIAN Brazil, with FIAN International and the Conselho Indigenista Missionário (CIMI): Missionary Council of Indig- enous Peoples, with support from HEKS/EPER, Brot für die Welt and Misereor. Author Photography Thaís Franceschini Ruy Sposati/CIMI Alex del Rey/FIAN International Revision Valéria Burity/FIAN Brazil Valéria Burity Flavio Valente Graphic Design Angélica Castañeda Flores www.boibumbadesign.com.br Felipe Bley Folly Lucas Prates This document is based on “The Guarani and Kaiowá Peoples’ Human Right to Adequate Food and Nutrition – a holistic approach”, which was written by Thaís Franceschini and Valéria Burity and revised by Flavio Valente and An- gélica Castañeda Flores. The document in which this Executive Summary is based offers an interpretation of the socio-economic and nutritional research that FIAN Brazil and CIMI-MS (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - Regional Mato Grosso do Sul: Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples - Mato Grosso do Sul Region) carried out in 2013 in three emblematic communities – Guaiviry, Ypo’i and Kurusu Ambá. The research in reference was coordinated by Célia Varela (FIAN Brazil) and CIMI-MS, and it was carried out by a team of specialists, consultants and contributors responsible for the fieldwork and the data system- atization. -

GOING to SEE a MAN HANGED Page 1 of 10

GOING TO SEE A MAN HANGED Page 1 of 10 GOING TO SEE A MAN HANGED. By WILLIAM MAKEPEACE THACKERAY JULY 1840. X-- , who had voted with Mr. Ewart for the abolition of the punishment of death, was anxious to see the effect on the public mind of an execution, and asked me to accompany him to see Courvoisier killed. We had not the advantage of a sheriffs order, like the "six hundred noblemen and gentlemen" who were admitted within the walls of the prison; but determined to mingle with the crowd at the foot of the scaffold, and take up our positions at a very early hour. As I was to rise at three in the morning, I went to bed at ten, thinking that five hours' sleep would be amply sufficient to brace me against the fatigues of the coming day. But, as might have been expected, the event of the morrow was perpetually before my eyes through the night, and kept them wide open. I heard all the clocks in the neighbourhood chime the hours in succession; a dog from some court hard by kept up a pitiful howling; at one o'clock, a cock set up a feeble melancholy crowing; shortly after two the daylight came peeping grey through the window- shutters; and by the time that X-- arrived, in fulfilment of his promise, I had been asleep about half-an-hour. He, more wise, had not gone to rest at all, but had remained up all night at the Club along with Dash and two or three more. -

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London Christine Winter Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Royal Holloway, University of London, 2012 2 Declaration I, Christine Winter, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 3 Abstract In the history of crime and punishment the prisons of medieval London have generally been overlooked. This may have been because none of the prison records have survived for this period, yet there is enough information in civic and royal documents, and through archaeological evidence, to allow a reassessment of London’s prisons in the later middle ages. This thesis begins with an analysis of the purpose of imprisonment, which was not merely custodial and was undoubtedly punitive in the medieval period. Having established that incarceration was employed for a variety of purposes the physicality of prison buildings and the conditions in which prisoners were kept are considered. This research suggests that the periodic complaints that London’s medieval prisons, particularly Newgate, were ‘foul’ with ‘noxious air’ were the result of external, rather than internal, factors. Using both civic and royal sources the management of prisons and the abuses inflicted by some keepers have been analysed. This has revealed that there were very few differences in the way civic and royal prisons were administered; however, there were distinct advantages to being either the keeper or a prisoner of the Fleet prison. Because incarceration was not the only penalty available in the enforcement of law and order, this thesis also considers the offences that constituted a misdemeanour and the various punishments employed by the authorities. -

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 2 (2019) ii e-ISSN: 2450-4580 Publisher: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Lublin, Poland Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press MCSU Library building, 3rd floor ul. Idziego Radziszewskiego 11, 20-031 Lublin, Poland phone: (081) 537 53 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictwo.umcs.lublin.pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Anna Maziarczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka, Lublin University of Technology, Poland International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Hungary Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ruba Fahmi Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan Alejandro Curado, University of Extramadura, Spain Saadiyah Darus, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Janusz Golec, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Margot Heinemann, Leipzig University, Germany Christophe Ippolito, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States of America Vita Kalnberzina, University of Riga, Latvia Henryk Kardela, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ferit Kilickaya, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Turkey Laure Lévêque, University of Toulon, France Heinz-Helmut Lüger, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Peter Schnyder, University of Upper Alsace, France Alain Vuillemin, Artois University, France v Indexing Peer Review Process 1. Each article is reviewed by two independent reviewers not affiliated to the place of work of the author of the article or the publisher. 2. For publications in foreign languages, at least one reviewer’s affiliation should be in a different country than the country of the author of the article. -

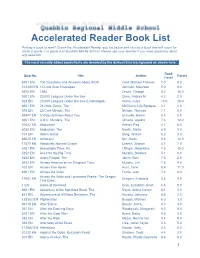

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

The Poor in England Steven King Is Reader in History at Contribution to the Historiography of Poverty, Combining As It Oxford Brookes University

king&t jkt 6/2/03 2:57 PM Page 1 Alannah Tomkins is Lecturer in History at ‘Each chapter is fluently written and deeply immersed in the University of Keele. primary sources. The work as a whole makes an original The poor in England Steven King is Reader in History at contribution to the historiography of poverty, combining as it Oxford Brookes University. does a high degree of scholarship with intellectual innovation.’ The poor Professor Anne Borsay, University of Wales, Swansea This fascinating collection of studies investigates English poverty in England between 1700 and 1850 and the ways in which the poor made ends meet. The phrase ‘economy of makeshifts’ has often been used to summarise the patchy, disparate and sometimes failing 1700–1850 strategies of the poor for material survival. Incomes or benefits derived through the ‘economy’ ranged from wages supported by under-employment via petty crime through to charity; however, An economy of makeshifts until now, discussions of this array of makeshifts usually fall short of answering vital questions about how and when the poor secured access to them. This book represents the single most significant attempt in print to supply the English ‘economy of makeshifts’ with a solid, empirical basis and to advance the concept of makeshifts from a vague but convenient label to a more precise yet inclusive definition. 1700–1850 Individual chapters written by some of the leading, emerging historians of welfare examine how advantages gained from access to common land, mobilisation of kinship support, crime, and other marginal resources could prop up struggling households. -

Nineteenth Century Legal Treatises Procedural Law Fiche Listing

Nineteenth Century Legal Treatises Procedural Law Fiche Listing Bigelow, Melville Madison, 1846-1921. Maddock, Henry, d. 1824. A treatise on the law of estoppel : and its A treatise on the principles and practice of the application in practice. High Court of Chancery : under the following heads, Boston : Little, Brown. 1886 I. Common law jurisdiction of the chancellor. II. Equity Equity jurisdiction of the chancellor. III. Statutory lvii, 765 p. ; 24 cm.; US-92-1; 4th ed. jurisdiction of the chancellor. IV. Specially delegated Fiche: 20805-20813 jurisdiction of the chancellor. London : W. Clarke and Sons. 1815 Bigelow, Melville Madison, 1846-1921. Equity A treatise on the law of estoppel : and its 2 v. ; 23 cm.; UK-92-4. application in practice. Fiche: 29122-29135 Boston : Little, Brown. 1876 Equity Will, John Shiress, 1840-1910. lxviii, 603 p. ; 24 cm.; US-92-2; 2nd ed. The practice of the referees' courts, in Parliament : Fiche: 20814-20821 in regard to engineering details, efficiency of works, and estimates, and water and gas bills : with a chapter Bigelow, Melville Madison, 1846-1921. on claims to compensation. A treatise on the law of estoppel : and its London : Stevens and Sons. 1866 application in practice. Practice & Procedure Boston : Little, Brown. 1882 xxi, 340 p. ; 23 cm.; UK-90-1. Equity Fiche: 33727-33730 lxxxiii, 675 p. ; 24 cm.; US-92-3; 3rd ed. Fiche: 20822-20829 Glyn, Lewis E. (Lewis Edmund), 1849-1919. The jurisdiction and practice of the Mayor's Court O'Conor, Charles, 1804-1884. : together with appendices of forms, rules, and Heath-Ingersoll arbitration : decision and award of statutes specially relating to the court.--2nd ed. -

Engaging the Trope of Redemptive Suffering: Inmate Voices in the Antebellum Prison Debates

Engaging thE tropE of rEdEmptivE SuffEring: inmatE voicES in thE antEbEllum priSon dEbatES Jennifer Graber n 1842 American Sunday-School Union pamphlet presented the ideal prisoner. According to the text, Jack Hodges—a convicted Amurderer serving a twenty-one-year sentence at New York’s Auburn Prison—admitted his guilt, displayed proper penitence, reformed his behavior, and expressed thanks for his prison experi- ence. The Reverend Anson Eddy, who had interviewed Hodges in 1826, regaled readers with stories of Hodges’s modest upbring- ing and descent into lawlessness. He detailed Hodges’s crime, trial, and death sentence, which was later commuted to life imprisonment. According to Eddy, Hodges encountered upstand- ing prison staff and a kind chaplain at Auburn. In his solitary cell, the inmate read his Bible, which helped lead him from sin to grace. Not only did Hodges experience personal salvation, the prisoner committed himself to evangelizing others. Eddy’s pamphlet is full of quotations attributed to Hodges, including the inmate’s claim that “I loved [Auburn]. I loved the prison, for there I first met Jesus.”1 pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 2, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 15:39:26 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.2_04_Graber.indd 209 18/04/12 12:28 AM pennsylvania history While Eddy’s pamphlet, like so much antebellum religious literature, focused on the story of an ideal convert, it also featured social commentary on the nation’s prisons. -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022. -

Evil in the 'City of Angels'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! April 24 - 30, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 W L M C A B L R G R C S P L N Your Key 2 x 3" ad P E Y S W Z A Z O V A T T O F L K D G U E N R S U H M I S J To Buying D O I B N P E M R Z Y U S A F and Selling! N K Z N U D E U W A R P A N E 2 x 3.5" ad Z P I M H A Z R O Q Z D E G Y M K E P I R A D N V G A S E B E D W T E Z P E I A B T G L A U P E M E P Y R M N T A M E V P L R V J R V E Z O N U A S E A O X R Z D F T R O L K R F R D Z D E T E C T I V E S I A X I U K N P F A P N K W P A P L Q E C S T K S M N T I A G O U V A H T P E K H E O S R Z M R “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lewis (Michener) (Nathan) Lane Supernatural Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Magda (Natalie) Dormer (1938) Los Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Tiago (Vega) (Daniel) Zovatto (Police) Detectives Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Evil in the Peter (Craft) (Rory) Kinnear Murder County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Maria (Vega) (Adriana) Barraza Espionage Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘City of Angels’ for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com Natalie Dormer stars in “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels,” All specials are pre-paid. -

The Rise of Prisons and the Origins of the Rehabilitative Ideal

Michigan Law Review Volume 77 Issue 3 1979 The Rise of Prisons and the Origins of the Rehabilitative Ideal Carl E. Schneider University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Carl E. Schneider, The Rise of Prisons and the Origins of the Rehabilitative Ideal, 77 MICH. L. REV. 707 (1979). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol77/iss3/27 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF PRISONS AND THE ORIGINS OF THE REHABILITATIVE IDEAL Carl E. Schneider* THE DISCOVERY OF THE ASYLUM: SOCIAL ORDER AND DISORDER IN THE NEW REPUBLIC. By David J. Rothman. Boston: Little, Brown. 1971. Pp. xx, 376. $12.50. I. INTRODUCTION In 1971, David Rothman published this appealing and pro vocative study of the rise of the large custodial institution-the penitentiary, the insane asylum, and the almshouse-in Jack sonian America. The Discovery of the Asylum has been influen tiaP and remains the best general treatment of prisons in antebel lum America. 2 It merits careful, though cautious, attention from the legal community. This essay attempts to give it that attention and to use the opportunity to begin to explore a significant but little-studied question: When did what Professor Allen has called the rehabilitative ideal3 first begin to be taken seriously in Eng land and the United States? A review of Rothman's book invites that inquiry because an examination of the book's two main • Editor-in-Chief, Michigan Law Review.-Ed. -

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Volume 14 2013 Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies ISSN: 1533-2535 Special Issue: The Drug Policy Debate FOREIGN POLICY AND SECURITY ISSUES THE DRUG POLICY DEBATE Michael Kryzanek, China, United States, and Latin A Selection of Brief Essays Representing America: Challenges and Opportunities the Diversity of Opinion, Contributors: Marilyn Quagliotti, Timothy Lynch, Hilton McDavid and Noel M. Cowell, A Peter Hakim (with Kimberly Covington), Perspective on Cutting Edge Research for Crime and Craig Deare, AMB Adam Blackwell, and Security Policies and Programs in the Caribbean General (ret.) Barry McCaffrey Tyrone James, The Growth of the Private Security Industry in Barbados: A Case Study BOOK REVIEWS Phil Kelly, A Geopolitical Interpretation of Security Joseph Barron: Review of Max Boot, Concerns within United States–Latin American Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Relations Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present Emily Bushman: Review of Mark FOCUS ON BRAZIL Schuller, Killing With Kindness: Haiti, Myles Frechette and Frank Samolis, A Tentative International Aid, and NGOs Embrace: Brazil’s Foreign and Trade Relations with Philip Cofone: Review of Gastón Fornés the United States and Alan Butt Philip, The China–Latin Salvador Raza, Brazil’s Border Security Systems America Axis: Emerging Markets and the Initiative: A Transformative Endeavor in Force Future of Globalisation Design Cole Gibson: Review of Rory Carroll, Shênia K. de Lima, Estratégia Nacional de Defesa Comandante: