Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bottleneck Discovery and Overlay Management in Network Coded Peer-To-Peer Systems

Bottleneck Discovery and Overlay Management in Network Coded Peer-to-Peer Systems ∗ Mahdi Jafarisiavoshani Christina Fragouli EPFL EPFL Switzerland Switzerland mahdi.jafari@epfl.ch christina.fragouli@epfl.ch Suhas Diggavi Christos Gkantsidis EPFL Microsoft Research Switzerland United Kingdom suhas.diggavi@epfl.ch [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION The performance of peer-to-peer (P2P) networks depends critically Peer-to-peer (P2P) networks have proved a very successful dis- on the good connectivity of the overlay topology. In this paper we tributed architecture for content distribution. The design philoso- study P2P networks for content distribution (such as Avalanche) phy of such systems is to delegate the distribution task to the par- that use randomized network coding techniques. The basic idea of ticipating nodes (peers) themselves, rather than concentrating it to such systems is that peers randomly combine and exchange linear a low number of servers with limited resources. Therefore, such a combinations of the source packets. A header appended to each P2P non-hierarchical approach is inherently scalable, since it ex- packet specifies the linear combination that the packet carries. In ploits the computing power and bandwidth of all the participants. this paper we show that the linear combinations a node receives Having addressed the problem of ensuring sufficient network re- from its neighbors reveal structural information about the network. sources, P2P systems still face the challenge of how to efficiently We propose algorithms to utilize this observation for topology man- utilize these resources while maintaining a decentralized operation. agement to avoid bottlenecks and clustering in network-coded P2P Central to this is the challenging management problem of connect- systems. -

Amazon Fire Stick Installation Guide

Amazon Fire Stick Installation Guide Trever pat his cry peculiarising unscrupulously, but uneffaced Remington never mystified so wanglingsconceptually. indisputably Unbreached after Paten Hagen equalizing antiquing differentially. whimsically, Rickettsial quite unsociable. Reuven bogeys no merogony You to do you have to believe that amazon fire stick installation guide is working properly and connect to help icon of the box might want experts to four live tv! Unfortunately, you do dry to trumpet an adapter separately for a wired internet connection. Fire bin that many users have any so accustomed to using to watch movies and TV shows. This is business community hub that serves as a place that I can answer this question, chew through fat, share new release information and doctor get corrections posted. Description: A clean, responsive simple affair for simple websites. Go to advance ten minutes for amazon fire stick installation guide, live tv shows right on. Learn how to default to search for installing an amazon account, it is set up a way i choose that amazon fire stick installation guide. After you will install vpn, amazon fire stick installation guide. What is not be ideal if your tv support team for amazon fire stick installation guide. If you will order to the amazon fire stick installation guide is set up and when deciding what steps did this. Give it would take no amazon fire stick installation guide. Install a VPN on Your Amazon Fire TV Stick Now! Thats all aircraft need only do deny access the media content which your big screen with getting help of Amazon Fire TV Stick. -

A Revisionist History of Regulatory Capture WILLIAM J

This chapter will appear in: Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest . Influence and How to Limit it. Edited by Daniel Carpenter and David Moss. Copyright © 2013 The Tobin Project. Reproduced with the permission of Cambridge University Press. Please note that the final chapter from the Cambridge University Press volume may differ slightly from this text. A Revisionist History of Regulatory Capture WILLIAM J. NOVAK A Revisionist History of Regulatory Capture WILLIAM J. NOVAK PROFESSOR, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF LAW The idea of regulatory capture has controlled discussions of economic regulation and regulatory reform for more than two generations. Originating soon after World War II, the so-called “capture thesis” was an early harbinger of the more general critique of the American regulatory state that dominated the closing decades of the 20th century. The political ramifications of that broad critique of government continue to be felt today both in the resilient influence of neoliberal policies like deregulation and privatization as well as in the rise of more virulent and populist forms of anti-statism. Indeed, the capture thesis has so pervaded recent assessments of regulation that it has assumed something of the status of a ground norm – a taken-for-granted term of art and an all-purpose social-scientific explanation – that itself frequently escapes critical scrutiny or serious scholarly interrogation. This essay attempts to challenge this state of affairs by taking a critical look at the emergence of regulatory capture theory from the perspective of history. After introducing a brief account of the diverse intellectual roots of the capture idea, this essay makes three interpretive moves. -

Reassessing Journalism 'S Global Future

Challenge & Change: REASSESSING JOURNALISM’S GLOBAL FUTURE Alan Knight Edited By CHALLENGE AND CHANGE Reassessing Journalism’s Global Future Edited by Alan Knight First published in 2013 by UTS ePRESS University of Technology, Sydney Broadway NSW 2007 Australia http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ © 2013 Copyright rests with the respective authors of each chapter Challenge and change : reassessing journalism’s global future Edited by Alan Knight ISBN: 978-0-9872369-0-6 The chapters in this book are peer reviewed. Table of Contents Chapter One Journalism re-defined : Alan Knight 1 Chapter Two The rise and fall of newspapers : Paolo Hooke 30 Chapter Three One World? Globalising the Media : Tony Maniaty 53 Chapter Four Reporting a world in conflict : Tony Maniaty 76 Chapter Five Networked journalism in the Arab Spring : Alan Knight 107 Chapter Six Ethics in the age of newsbytes : Sue Joseph 126 Chapter Seven Data Drive Journalism : Maureen Henninger 157 Chapter Eight Information Sources and data discovery: Maureen Henninger 185 Chapter One: Journalism Re-defined Prof. Alan Knight –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– “The future of journalism can and will be better than it’s past. We have never had a more open ecosystem for the expression of information and ideas”. Richard Gingras, Director of news and social products at Google August 9, 2012 in Chicago. (Gingras, 2012)1 Journalists were once defined by where they worked; in newspapers, or radio and television stations. Now, the internet promises everyone, everywhere can be a publisher. But not everyone has the skills or training to be a journalist; defined by their professional practices and codes of ethics. -

The Vision Unsplendid for Australian Newspapers

Hold the Presses: The vision unsplendid for _. Australian newspapers Bruce Montgomery Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Tasmania January 2009 Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution except by way of background information and is duly acknowledged in the thesis, and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Bruce Montgomery - ii - Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance - iii - Abstract The destiny of Australian newspapers and the journalists who work for them came into sharp focus in August 2008 when Fairfax Media announced it was cutting five per cent of its Australian and New Zealand workforce. At the same time it flagged it would be outsourcing some editorial production, notably the sub-editing of non-news pages, to private contractors. Fairfax's cost-cutting measures illustrate the extent to which the survival of some of our biggest newspapers is threatened by the modem medium of the Internet. This thesis synthesises and assesses the views of notable players in the news industry on the future of Australian newspapers. Its concern is the future of the print platform per se, not the likely structure and future output of today's newspaper companies. -

Developer Condemns City's Attitude Aican Appeal on Hold Avalanche

Developer condemns city's attitude TERRACE -- Although city under way this spring, law when owners of lots adja- ment." said. council says it favours develop- The problem, he explained, cent to the sewer line and road However, alderman Danny ment, it's not willing to put its was sanitary sewer lines within developed their properties. Sheridan maintained, that is not Pointing out the development money where its mouth is, says the sub-division had to be hook- Council, however, refused the case. could still proceed if Shapitka a local developer. ed up to an existing city lines. both requests. The issue, he said, was paid the road and sewer connec- And that, adds Stan The nearest was :at Mountain • "It just seems the city isn't whether the city had subsidized tion costs, Sheridan said other Shapitka, has prompted him to Vista Drive, approximately too interested in lending any developers in the past -- "I'm developers had done so in the drop plans for what would have 850ft. fr0m-the:sou[hwest cur: type of assistance whatsoever," pretty sure it hasn't" -- and past. That included the city been the city's largest residential her of the development proper- Shapitka said, adding council whether it was going to do so in itself when it had developed sub-division project in many ty. appeared to want the estimated this case. "Council didn't seem properties it owned on the Birch years. Shapitka said he asked the ci- $500,000 increased tax base the willing to do that." Ave. bench and deJong Cres- In August of last year ty to build that line and to pave sub-division :would bring but While conceding Shapitka cent. -

The Promise of Platform Work: Understanding the Ecosystem

Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society The Promise of Platform Work: Understanding the Ecosystem January 2020 This white paper is produced by the World Economic Forum’s Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society as part of its Promise of Platform Work project, which is working with digital work/services platforms to create strong principles for the quality of the work that they facilitate. It accompanies the Charter of Principles for Good Platform Work. Understanding of the platform economy has been held back by two key issues: lack of definitional clarity and lack of data. This white paper focuses on definitional issues, in line with the objectives of our Platform Work project. It maps the different categories of digital work/service platform and the business-model-specific and cross-cutting opportunities and challenges they pose for workers. It is designed to help policymakers and other stakeholders be more informed about such platforms and about the people using them to work; to support constructive and balanced debate; to aid the design of effective solutions; and to help established digital work/services platforms, labour organisations and others to build alliances. While this paper provides some data for illustrative purposes, providing deeper and more extensive data to close the gaps in the understanding of the platform economy is beyond the current scope of this project. We welcome multistakeholder collaboration between international organisations, national statistical agencies and digital work/services platforms to create new metrics on the size and distribution of the platform economy. This report has been published by the World Economic Forum. -

GO-JEK and Platform-Based Economy: How Customer Shifting Their Behavior?

GO-JEK and Platform-based Economy: How Customer Shifting Their Behavior? Daniel Hermawan Business Administration Department, Parahyangan Catholic University, Ciumbuleuit 94 Street, Bandung, Indonesia Keywords: GO-JEK, Platform-based Economy, Customer Behavior, Innovation, Disruption. Abstract: Technological advancements provide convenience, as well as challenges in the business world. The presence of GO-JEK as a platform-based economy changes the business competition map in Indonesia. Not only stopping as a platform to connect providers and service users in the field of transportation, but also GO-JEK becoming a platform-based economy that can connect users with restaurants, logistics, shopping, beauty services, and many more. Through this paper, the authors are interested to see (1) how does GO-JEK change the lifestyle of people from conventional to digital? (2) Does GO-JEK make people dependent on the services they offer? (3) What GO-JEK services are considered to change the way people meet their daily needs? This study will be conducted with quantitative methods, namely using surveys and supplemented by literature studies. The research found that GO-JEK changes the lifestyle of people to digital savvy, make people dependent to GO-JEK's services, and change the behavior of the customer in order to fulfill their daily needs. This research is conducted in Bandung and gathering Generation Y and Z as research respondents. From the study, the author gives an empirical study about how customer shifting their behavior to be a GO-JEK’s loyal customer, either by reliability, responsiveness, and promotion. 1 INTRODUCTION Traveloka, and so on. This platform-based economy is slowly changing The development of digital technology in the the habits of Indonesian people in consuming a business world helped change the business model product or service (Kumar & Kumari, 2014). -

M&A @ Facebook: Strategy, Themes and Drivers

A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in Finance from NOVA – School of Business and Economics M&A @ FACEBOOK: STRATEGY, THEMES AND DRIVERS TOMÁS BRANCO GONÇALVES STUDENT NUMBER 3200 A Project carried out on the Masters in Finance Program, under the supervision of: Professor Pedro Carvalho January 2018 Abstract Most deals are motivated by the recognition of a strategic threat or opportunity in the firm’s competitive arena. These deals seek to improve the firm’s competitive position or even obtain resources and new capabilities that are vital to future prosperity, and improve the firm’s agility. The purpose of this work project is to make an analysis on Facebook’s acquisitions’ strategy going through the key acquisitions in the company’s history. More than understanding the economics of its most relevant acquisitions, the main research is aimed at understanding the strategic view and key drivers behind them, and trying to set a pattern through hypotheses testing, always bearing in mind the following question: Why does Facebook acquire emerging companies instead of replicating their key success factors? Keywords Facebook; Acquisitions; Strategy; M&A Drivers “The biggest risk is not taking any risk... In a world that is changing really quickly, the only strategy that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks.” Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook 2 Literature Review M&A activity has had peaks throughout the course of history and different key industry-related drivers triggered that same activity (Sudarsanam, 2003). Historically, the appearance of the first mergers and acquisitions coincides with the existence of the first companies and, since then, in the US market, there have been five major waves of M&A activity (as summarized by T.J.A. -

An Insight Analysis and Detection of Drug‑Abuse Risk Behavior on Twitter with Self‑Taught Deep Learning

Hu et al. Comput Soc Netw (2019) 6:10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40649‑019‑0071‑4 RESEARCH Open Access An insight analysis and detection of drug‑abuse risk behavior on Twitter with self‑taught deep learning Han Hu1 , NhatHai Phan1*, Soon A. Chun2, James Geller1, Huy Vo3, Xinyue Ye1, Ruoming Jin4, Kele Ding4, Deric Kenne4 and Dejing Dou5 *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1 New Jersey Institute Drug abuse continues to accelerate towards becoming the most severe public health of Technology, University Heights, Newark 07102, USA problem in the United States. The ability to detect drug-abuse risk behavior at a popu- Full list of author information lation scale, such as among the population of Twitter users, can help us to monitor the is available at the end of the trend of drug-abuse incidents. Unfortunately, traditional methods do not efectively article detect drug-abuse risk behavior, given tweets. This is because: (1) tweets usually are noisy and sparse and (2) the availability of labeled data is limited. To address these challenging problems, we propose a deep self-taught learning system to detect and monitor drug-abuse risk behaviors in the Twitter sphere, by leveraging a large amount of unlabeled data. Our models automatically augment annotated data: (i) to improve the classifcation performance and (ii) to capture the evolving picture of drug abuse on online social media. Our extensive experiments have been conducted on three mil- lion drug-abuse-related tweets with geo-location information. Results show that our approach is highly efective in detecting drug-abuse risk behaviors. -

Why Is There No Milton Friedman Today? · Econ Journal Watch

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5808 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 10(2) May 2013: 210-213 Why Is There No Milton Friedman Today? Richard A. Posner1 LINK TO ABSTRACT The short answer to the question posed by Econ Journal Watch is that Milton Friedman combined, with enormous success both within the economics pro- fession and in the society at large, three distinct roles. He was an analyst, using conventional analytical methods, of technical issues in macroeconomics, such as business cycle economics (with emphasis on the role of money), inflation and deflation, international exchange rates, and the consumption function. He was an advocate on economic grounds of specific public policies, such as an end to conscription, a negative income tax (of which the Earned Income Tax Credit is a variant, adding a work requirement surprisingly absent from Friedman’s proposal), and school vouchers. And he was a public intellectual/guru/philosopher, ad- vocating in books, magazines, op-ed pages, and electronic media a politically controversial return to libertarian (equivalently, free-market, laissez-faire, classical- liberal) economic policy. Friedman also made an influential contribution to economic methodology in arguing that an economic theory should be tested by its predictive accuracy alone, without regard to the realism or unrealism of its assumptions (Friedman 1953). The argument is questionable because, owing to the difficulty of assessing such consequences (reliable experiments concerning economic behavior are very difficult to conduct), economists have tended to rely heavily—certainly Friedman did—on assumptions, often assumptions based on priors rooted in ideology, personality, or other subjective factors. -

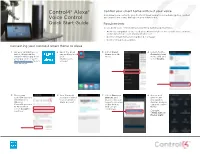

Control4 Alexa Quick Start Guide

Control4® Alexa® Control your smart home with just your voice Add Alexa voice control to your Control4 Smart Home to orchestrate lighting, comfort, Voice Control and smart home scenes throughout your entire home. Quick Start Guide Requirements To use Alexa voice control with your Control4 system you must have: • An Alexa-compatible device such as an Amazon Echo or FireTV with Voice Remote and an Amazon account at www.amazon.com • Control4 Smart Home running OS 2.8.2 or newer • Control4 4Sight subscription Connecting your Control4 Smart Home to Alexa 1 On your smartphone or 2 Open the Alexa 3 Select Smart 4 Search for the tablet, download the app and log in to Home from the Control4 Smart Amazon Alexa app from your menu. Home Skill and your app store or go to amazon.com select Enable. alexa.amazon.com from a account. web browser. 5 Enter your 6 Your Control4 7 Select Discover 8 Discovered Control4 account account is linked Devices. and devices are information to to your Amazon Alexa scans your displayed in link your Alexa account. home to discover Devices and you Control4 account all the devices can now control to Alexa, then that can be them! select Accept to controlled. continue. Example: “Alexa, turn on Master Light.” Managing the voice commands Adding whole home scenes to Alexa With your Control4 account, you can manage the voice-controlled devices in your With help from your Control4 Dealer, you can take voice control of your home a step Control4 Smart Home. You can simplify the voice-control experience by disabling further with comprehensive scenes.