The Lost Decade?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taylor's Residential Series™ Test Kits

Taylor’s Residential Series™ Test Kits INTRODUCTION aylor’s Residential Series™ test kits are designed for spa and pool owners who have low bather loads and test their water between visits from a service technician Tor trips to their pool supplies store. This series uses the same quality reagents as Taylor’s kits for professional analysts. Buyers have a choice of three progressively more sophisticated models: 3-Way, 6-Way, and 9-Way, as described below. Every Residential kit is available in our classic case—the solid blue, injection-molded plastic kit which is so durable it The K-1004 6-Way DPD kit monitors three variables that impact water can be refilled season after season. Tabs on every case make quality so problems can be detected and treated early, with less them easy to hang from hooks. expense. Residential kits feature .75 oz. reagents color-coded to 3-WAY (DPD) instructions; sanitizer values for both chlorine and bromine Free Chlorine .25–2.5 ppm testing; five sets of printed-color standards encased in Total Bromine .5–5 ppm plastic for longevity (calibrated to work with Taylor pH pH 6.8–8.2 reagents R-0014, R-0015, and R-0016); and molded fill English: K-1101 lines to ensure the correct sample size. Spanish: K-1101S Instructions are written in clear, nontechnical terms and Spanish version is available in a case pack of twelve (K-1101S-12) include pictograms for ease of following steps. Instruction 6-WAY (OT) cards printed on waterproof paper that resists fading and Total Chlorine .5–5 ppm tearing. -

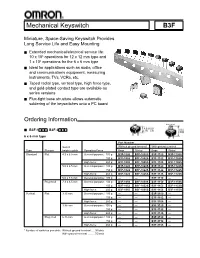

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

The Church Grows in Power. Essential Question

Big Idea The Church grows in power. Essential Question How did the Church gain power in Medieval Europe? Words To Know Secular – this means not-religious. Canon Laws – laws developed by the Church, based on the bible. Excommunication – the limiting or ending of a person’s membership in the Catholic Church. Holy Sacraments – sacred ceremonies of the church. Interdict – an order or ban from the church preventing a person or group of people from receiving holy sacraments in the Catholic Church. Words To Know Papal Supremacy – the authority or power of the Pope over all secular rulers (non religious rulers, including kings and emperors). Let’s Set The Stage… After the fall of the Roman Empire, western Europe broke into small warring kingdoms. Since it was the official church of the Roman Empire, most people in Western Europe were Christians. The Church owned a great deal of wealth and land. It became the most important unifying and stabilizing force in western Europe during the Middle Ages. The power vacuum left by the Roman Empire was filled by the Catholic Church. The Power of the Church The church was the center of medieval life in western Europe. Almost every village and town had a church building. Church bells rang out the hours, called people to worship and warned of danger. Over the course of the early Middle Ages, the Catholic Church became more influential and powerful, to the point where the Church and the beliefs of its clergy [people who had high positions in the Church like priests and bishops] controlled secular [non-religious] life and secular government. -

Department of Housing and Economic Development Employee Directory

Department of Housing and Economic Development Employee Directory Name Number Name Number Name Number HED Main Reception ADMINISTRATION Bureau of HOUSING 744-4190 City Hall - Room 1000 City Hall - Room 1003 Eager, Bill 744-9475 Sulewski, Patricia 744-6926 Customer Service 744-3653 Murawski, Peter 744-6228 Housing Preservation City Hall - Room 1006 EXECUTIVE OFFICE Human Resources (HR) Brutus, Patrick 744-7077 City Hall - Room 1000 Cannon, Angela 744-9610 Colinet, Ketsia 744-0141 Mooney, Andrew 744-9476 Henry, Amy 744-6330 Cowan, Darlene 744-9613 Gempeler, Amy 744-4133 Rodriguez, Betra 744-9061 Harrison, Kimberley 744-9782 Quesada, Yolanda 744-9362 Ryan, Lenore 744-4180 Lewis, Edward 744-4461 Wilson, Lynette 744-9445 Thomas, Hattie 744-8282 Ludwig, Katie 744-0268 IT/GIS/Research Simpkins, Anthony 744-9777 Bureau of Housing Ahmed, Rizwana 744-7222 Smith, Angelique 744-1082 Eager, Bill 744-9475 Hague, Robert 744-5204 Homeownership Center Sulewski, Patricia 744-6926 Imparl, Paul 744-9234 City Hall - Room 1006 Karnuth, John 744-0263 Alarcon, Luis 744-0835 Bureau of Economic Development Perry, Susan 744-4154 Barth, Leona 744-0891 Jasso, Michael 744-0771 Phillips, Stavros 744-2714 Baxter, Marcia 744-0696 Castillo, Isabel (Liz) 744-0919 Raya, Josephine 744-0756 Breems, Kara 744-6746 Scales, Cherie 744-0844 Daniels, Alberta 744-0857 Bureau of Planning & Zoning Williams, Cora 744-0894 Davis, Anita 744-0841 City Hall - Room 905 Office Operations Gibson, Regina 744-0070 Scudiero, Patti 744-5765 Davis, Lance 744-2075 Hall, Jonathan 744-0826 Reblin, -

Electric Actuators Vsi-1000 Series

ELECTRIC ACTUATORS TM VSI-1000 SERIES DESCRIPTION VSI-1000 Series Electric Actuators are used on Kele KBV Series butterfly valves to provide two-position (with or without battery backup) or proportional control in a NEMA 4X housing. The VSI-1000 Series comes standard on 8" and larger non-spring return assemblies and on 5" and larger two- position spring return assemblies. They can be ordered on smaller valve assemblies as an option. Standard fea- tures include 2 SPDT fully adjustable auxiliary switches KBV-2-6-E2SO (two-position only), manual override crank, and an inter- assembly includes nal heater to prevent condensation in outdoor installa- VSI-BB1020 actuator tions. SPECIFICATIONS FEATURES Power 120 VAC standard •Lightweight, compact design Models 1005 to 1020 12/24 VDC optional • Two-position or modulating control Models 1005 to 1040 24 VAC optional • Two-position battery-backed models Torque range 347-17,359 in-lb • NEMA 4X watertight, corrosion-resistant housing Motor 120 VAC, 1 phase, 60 Hz; • Integral position indicator enclosed, non-ventilated, high • Space heater standard starting torque, reversible induc- • Two 1/2" conduit connections tion, Class E insulation • Detachable manual override crank Thermal overload Auto reset, embedded • Terminal strip wiring Travel limit switches Cam operated, adjustable SPDT • Worm gear drive, no electro-mechanical brake for open/close stop required • Mounting orientation in any direction Position indicator High-visibility graduated dial • 4-20 mA or 500Ω optional feedback signal Conduit connections -

FY2020-2029 Decade Plan

Table of Contents Section 1 – Introduction Section 2 – Decade Plan Spreadsheets Spreadsheet 1: Summary of Projects Spreadsheet 2: Level 1 Priority Renewal Projects Spreadsheet 3: Water 2120 Projects Spreadsheet 4: Special Projects and Priority 1 Growth Projects Spreadsheet 5: Priority 2 Growth Projects Section 3 – Project Summary Sheets Basic Renewal Program Category 100: Sanitary Sewer Pipelines Category 200: Drinking Water Pipelines Category 300: Southside Reclamation Plant (SWRP) Category 400: Soil Amendment Facility (SAF) Category 500: Lift Stations and Vacuum Stations Category 600: Odor Control Facilities Category 700: Drinking Water Plant: Groundwater System Category 800: Drinking Water Plant: Treatment Systems Category 900: Reuse Line and Plant Category 1000: Compliance Category 1100: Shared Facilities Category 1200: Franchise Agreement Compliance Category 1300: Vehicles and Heavy Equipment Water 2120 Projects Category 8000: Water 2120 Projects Special Projects Category 9400: Special Projects Growth Projects Category 2000: Drinking Water Plant Growth Category 2100: Arsenic Treatment Growth Category 2200: Wastewater Facility Growth Category 2300: Water Lines Growth Category 2400: Land Acquisition Category 2500: Other Agreements Category 2600: Water Rights and Storage Category 2700: Development Agreements Category 2800: MIS/GIS Category 2900: Vehicles and Heavy Equipment Category 3000: Utility Risk Reduction Category 3100: Master Plans Category 3200: Miscellaneous Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority Decade Plan 2020 – 2029 INTRODUCTION Background The Decade Plan for the Water Authority is developed every two years and describes the proposed Capital Improvement Program (CIP) spending for the next ten years. The Decade Plan provides a direct link from the Water Authority’s financial plan to the proposed capital needs. The Decade Plan outlines projects in the Basic Program, Special Projects and the Growth funding categories. -

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea Region

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication A chronology of the history 7 of the Baltic Sea region Kristian Gerner 800-1250 Vikings; Early state formation and Christianization 800s-1000s Nordic Vikings dominate the Baltic Region 919-1024 The Saxon German Empire 966 Poland becomes Christianized under Mieszko I 988 Kiev Rus adopts Christianity 990s-1000s Denmark Christianized 999 The oldest record on existence of Gdańsk Cities and towns During the Middle Ages cities were small but they grew in number between 1200-1400 with increased trade, often in close proximity to feudal lords and bishops. Lübeck had some 20,000 inhabitants in the 14th and 15th centuries. In many cities around the Baltic Sea, German merchants became very influential. In Swedish cities tensions between Germans and Swedes were common. 1000s Sweden Christianized 1000s-1100s Finland Christianized. Swedish domination established 1025 Boleslaw I crowned King of Poland 1103-1104 A Nordic archbishopric founded in Lund 1143 Lübeck founded (rebuilt 1159 after a fire) 1150s-1220s Denmark dominates the Baltic Region 1161 Visby becomes a “free port” and develops into an important trade center 1100s Copenhagen founded (town charter 1254) 1100s-1200s German movement to the East 1200s Livonia under domination of the Teutonic Order 1200s Estonia and Livonia Christianized 1201 Riga founded by German bishop Albert 1219 Reval/Tallinn founded by Danes ca 1250 -

The Canterbury Tales and Its Times Library Research Guide

The Canterbury Tales and Its Times Library Research Guide McShain Library La Salle College High School SCOPE OR BAC8605KGR CheltenhamOUND Avenue Wyndmoor, PA 19038-7199 215-233-2911 SCOPE OR BACKGROUND This research guide lists a selected guide to resources available in our library on the topic of life in during the time of the Canterbury Tales. The Canterbury Tales is a collection of tales written in verse and set in the late 1300’s. The collection was begun around 1386. This era is called medieval times or the time of the middle ages. The Middle Ages is the period between ancient and modern times in Western Europe. It extends from the end of the Roman Empire (from about A.D. 400’s) to the 1500’s. INTRODUCTION TO THE TOPIC “Canterbury Tales” in Literature and Its Times, vol. 1, p. 64 – 70. R 809 LIT KEY DATES AND TIMES Black Death – 1300s A.D. (CE) Crusades – 1096 – 1270 A.D. (CE) Feudal Europe – 900s – 1000s A.D. (CE) High Middle Ages – between 1000s and the late 1200s A.D. (CE) Late Middle Ages – 1300s – 1500s A.D. (CE) Timelines on File: the Ancient and Medieval World (Prehistory – 1500 CE). R 902 TIM Scarre, Christopher. Smithsonian Timelines of the Ancient World. R 930 SMI KEYWORDS FOR SEARCHES Chaucer, Geoffrey Medieval Middle ages BROWSE FOR BOOKS USING THESE CALL NUMBERS Middle Ages, Europe – 940.1 Chaucer, Geoffrey – 821.1, 821.5 Religion – 200s 1 GRAPHICS, MAPS, DIAGRAMS, CHARTS, PHOTOGRAPHS, ETC. Curriculum Resource Center http://www.fofweb.com?Direct2.asp?ID=11900&ItemID=WE51 Historical Maps I. -

1000S - Early Warning System Errors

1000s - Early Warning System Errors Error codes below relate to Early Warning System (EWS): Error number Error message Additional info and instruction 1001 Your test has been saved. Please notify Connectivity issues likely caused this error. your test administrator. Follow the on-screen instructions. 1002 Please notify your test administrator. The designated save location is not writable or due to the inability to save a Saved Response File after test content has been viewed. Follow the on-screen instructions. 1003 Unable to save response file (at beginning The designated location for saving a of test) response file (as a backup in case of network interruption) is not writable. TestNav cannot connect to the servers, or cannot save the Saved Response File after the test content has been viewed. Click Exit Test and contact your local technical support to determine why the save locations are not working and there is a loss of connectivity. Resume the student or contact your school assessment coordinator to resume the student. The student should log in and continue testing. 1004 Unable to save response file (during test) Each operating system platform handles the EWS response file a bit differently. When displayed, the messages will include instructions unique to the platform being used for dealing with the error. This message is displayed when all of the below are true: The student has visited one or more items. The Saved Response File cannot be saved to any of the designated locations. TestNav is unable to successfully send responses to Pearson. The test has not yet been exited or submitted. -

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages After the collapse of Rome, Western Europe entered a period of political, social, and economic decline. From about 500 to 1000, invaders swept across the region, trade declined, towns emptied, and classical learning halted. For those reasons, this period in Europe is sometimes called the “Dark Ages.” However, Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions eventually blended, creating the medieval civilization. This period between ancient times and modern times – from about 500 to 1500 – is called the Middle Ages. The Frankish Kingdom The Germanic tribes that conquered parts of the Roman Empire included the Goths, Vandals, Saxons, and Franks. In 486, Clovis, king of the Franks, conquered the former Roman province of Gaul, which later became France. He ruled his land according to Frankish custom, but also preserved much of the Roman legacy by converting to Christianity. In the 600s, Islamic armies swept across North Africa and into Spain, threatening the Frankish kingdom and Christianity. At the battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel led the Frankish army in a victory over Muslim forces, stopping them from invading France and pushing farther into Europe. This victory marked Spain as the furthest extent of Muslim civilization and strengthened the Frankish kingdom. Charlemagne After Charlemagne died in 814, his heirs battled for control of the In 786, the grandson of Charles Martel became king of the Franks. He briefly united Western empire, finally dividing it into Europe when he built an empire reaching across what is now France, Germany, and part of three regions with the Treaty of Italy. -

Chapter 25: the Church, 1000 AD

0380-0397 CH25-846240 11/7/02 5:55 PM Page 380 CHAPTER The Church 25 1000 A.D.–1300 A.D. ᭣ Christian crusader and his wife ᭣ Enameled cross 1071 A.D. 1096 A.D. 1129 A.D. 1212 A.D. 1291 A.D. Seljuq Turks Start of the Inquisition Children’s Muslims win the conquer Jerusalem Crusades begins Crusade Crusades 380 UNIT 8 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES 0380-0397 CH25-846240 11/16/02 8:40 AM Page 381 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • How the Roman Catholic Church influenced life during the at humanheritage.glencoe.com Middle Ages. and click on Chapter 25— • What attempts were made to reform the Church during the Chapter Overviews to preview Middle Ages. this chapter. • What learning was like during the Middle Ages. • Why the Crusades took place during the Middle Ages. • What the effects of the Crusades were. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate mass Gregory VII Cluny tithes Francis of Assisi Palestine cathedrals Thomas Aquinas Outremer unions Urban II Venice chancellor Saladin Acre crusades Richard the emirs Lionheart Why It’s Important Leaders in the Roman Catholic Church wanted to develop a civilization in western Europe that was based on Christian ideals. By 1000, missionary monks had brought the Church’s teachings to most of Europe. They con- verted people and built new churches and monasteries. The Roman Catholic Church united western Europeans and took the lead in government, law, art, and learning for hundreds of years. The Church helped pass on the heritage of the Roman Empire. -

B3W-1050 Datasheet (PDF)

Sealed Tactile Switch B3W Through-hole-mounting Switches That Are Mounting-compatible with B3F Series. Sealed Structure for High Reliability • Sealed construction conforming to IP67 (IEC- 60529) provides high reliability in locations exposed to dust or water. (* Excluding the termi- nal section.) • Available in two sizes: 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm sizes. • Ground terminal available to protect against static electricity. • B32-series Key Tops mount to models with pro- jected plungers. RoHS Compliant ■ List of Models 6 × 6 mm Models Type Contact Plunger Height Operating Plunger Bags material force (OF) color Without Minimum Minimum With ground ground packing packing terminal terminal unit unit B3W-1000 Silver Flat type 4.3 mm 1.57 N {160 gf} White B3W-1000 B3W-1100 Series plated max. 2.26 N {230 gf} Yellow B3W-1002 B3W-1102 max. 5.0 mm 1.57 N {160 gf} White B3W-1020 --- max. 2.26 N {230 gf} Yellow B3W-1022 100 pcs --- 100 pcs max. Projected type 7.3 mm 1.57 N {160 gf} White B3W-1050 B3W-1150 max. 2.26 N {230 gf} Yellow B3W-1052 B3W-1152 max. Note: Bulk Packaged, 100 switches per bag. Order in multiples of the package quantity. 12 × 12 mm Models Type Contact Plunger Height Operating Plunger Bags material force (OF) color Without Minimum Minimum With ground ground packing packing terminal terminal unit unit B3W-4000 Silver Flat type 4.3 mm 1.96 N {200 gf} White B3W-4000 B3W-4100 Series plated max. 3.43 N {350 gf} Yellow B3W-4005 B3W-4105 max.