Karman and Compassion: Animals in the Jain Universal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One an Introduction to Jainism and Theravada

CHAPTER ONE AN INTRODUCTION TO JAINISM AND THERAVADA BUDDfflSM CHAPTER-I An Introduction to Jainism and Theravada Buddhism 1. 0. History of Jainism "Jainism is a system of faith and worship. It is preached by the Jinas. Jina means a victorious person".' Niganthavada which is mentioned in Buddhist literature is believed to be "Jainism". In those days jinas perhaps claimed themselves that they were niganthas. Therefore Buddhist literature probably uses the term 'nigantha' for Jinas. According to the definition of "Kilesarahita mayanti evamvaditaya laddhanamavasena nigantho" here nigantha (S. nkgrantha) means those who claimed that they are free from all bonds.^ Jainism is one of the oldest religions of the world. It is an independent and most ancient religion of India. It is not correct to say that Jainism was founded by Lord Mahavlra. Even Lord Parsva cannot be regarded as the founder of this great religion. It is equally incorrect to maintain that Jainism is nothing more than a revolt against the Vedic religion. The truth is that Jainism is quite an independent religion. It has its own peculiarities. It is flourishing on this land from times immemorial. Among Brahmanic and i^ramanic trends, Jainism, like Buddhism, represents ^ramanic culture. In Buddhist literatures, we can find so many 'GJ, 1 ^ DNA-l, P. 104 informations about Jainism. The Nigantha Nataputta is none else but Lord Mahavlra.^ 1.1. Rsabhadeva According to tradition, Jainism owes its origin to Rsabha, the first among the twenty-four Tirthankaras. The rest of the Trrthahkaras are said to have revived and revealed this ancient faith from time to time. -

Lord Mahavira Publisher's Note

LORD MAHAVIRA [A study in Historical Perspective] BY BOOL CHAND, M.A. Ph.D (Lond.) P. V. Research Institute Series: 39 Editor: Dr. Sagarmal Jain With an introduction by Prof. Sagarmal Jain P.V. RESEARCH INSTITUTE Varanasi-5 Published by P.V. Research Institute I.T.I. Road Varanasi-5 Phone:66762 2nd Edition 1987 Price Rs.40-00 Printed by Vivek Printers Post Box No.4, B.H.U. Varanasi-5 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 1 Create PDF with PDF4U. If you wish to remove this line, please click here to purchase the full version The book ‘Lord Mahavira’, by Dr. Bool Chand was first published in 1948 by Jaina Cultural Research Society which has been merged into P.V. Research Institute. The book was not only an authentic piece of work done in a historical perspective but also a popular one, hence it became unavailable for sale soon. Since long it was so much in demand that we decided in favor of brining its second Edition. Except some minor changes here and there, the book remains the same. Yet a precise but valuable introduction, depicting the relevance of the teachings of Lord Mahavira in modern world has been added by Dr. Sagarmal Jain, the Director, P.V. Research Institute. As Dr. Jain has pointed out therein, the basic problems of present society i.e. mental tensions, violence and the conflicts of ideologies and faith, can be solved through three basic tenets of non-attachment, non-violence and non-absolutism propounded by Lord Mahavira and peace and harmony can certainly be established in the world. -

Ahimsa and Vegetarianism

March , 2015 Vol. No. 176 Ahimsa Times in World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 14 Continuous Years Readership AHIMSA AND VEGETARIANISM MAHARASHTRA GOVERNMENT BANS COW SLAUGHTER: FIVE YEARS JAIL Mar. 3rd, 2015. Mumbai. The bill banning cow slaughter in Maharashtra, pending for several years, finally received the President's assent, which means red meat lovers in the state will have to do without beef. This measure has taken almost twenty years to materialize and was initiated during the previous Sena-BJP Government. The bill was first submitted to the President for approval on January 30, 1996.. However, subsequent Governments at the Centre, including the BJP led NDA stalled it and did not seek the President’s consent. A delegation of seven state BJP MPs led by Kirit Somaiya, (MP from Mumbai North) had met the President in New Delhi recently and submitted a memorandum seeking assent to the bill. The memorandum said that the Maharashtra Animal Preservation (Amendment) Bill, 1995, passed during the previous Shiv Sena-BJP regime, was pending for approval for 19 years. The law will ban beef from the slaughter of bulls and bullocks, which was previously allowed based on a fit- for-slaughter certificate. The new Act will, however, allow the slaughter of water buffaloes. The punishment for the sale of beef or possession of it could be prison for five years with an additional fine of Rs 10,000. It is notable that, Reuters new service had earlier reported that Hindu nationalists in India had stepped up attacks on the country's beef industry, seizing trucks with cattle bound for abattoirs and blockading meat processing plants in a bid to halt the trade in the world's second-biggest exporter of beef. -

August 2016 Jaindigest

August 2016 JainDigest YJA Convention 2016 - Los Angeles, California JAIN DIGEST A Publication of the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA) email: [email protected] JAINA is an umbrella organization of local Jain Associations in U.S.A. and Canada. The purpose of the organization is to preserve, practice, and promote Jain Dharma and Jain Way of life. JAINA Headquarters: 722 S Main St. Milpitas, CA 95035 Tele: 510-730-0204, email: [email protected], Web: www.jaina.org JAINA Executive Committee JAIN DIGEST Editorial Team 310-721-5947 President Ashok Domadia email: [email protected] [email protected] Jain Digest Committee Chairman First VP: Gunvant Shah Mahesh Wadher [email protected] Editors Treasurer: Rita Sheth Dilip Parekh [email protected] Sanjay Bhandari Yogendra Bobra Secretory: Shobha Vora Reena Shah [email protected] Allison Bergson VP Northeast: Dr. Mamta Shaha Art and Design [email protected] Jayana Shah Rishita Dagli VP Mideast: Prakash Mehta Pooja Shah [email protected] IT Support VP Midwest: Hemant T. Shah Giriraj Jain [email protected] Advertisements VP Southeast: Rajendra Mehta Mahesh Wadher [email protected] Shobha Vora VP Southwest: Pradeep Shah [email protected] VP West: Mahesh Wadher [email protected] VP Canada: Raj Patil [email protected] Past President: Prem Jain [email protected] YJA Chair: Puja Savla On the Cover: YJA Convention 2016 Attendees [email protected] Disclosure YJA Chair: Sunny Dharod The Editorial Team endeavors to publish all the materials that are [email protected] submitted but reserves the right to reduce, revise, reject, or edit any article, letter, or abstract for clarity, space, or policy reasons. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol III Issue IX June 2014 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Flávio de São Pedro Filho A R Burla College, India Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Ecaterina Patrascu Kamani Perera Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Advisory Board Flávio de São Pedro Filho Horia Patrascu Mabel Miao Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Ruth Wolf Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania University Walla, Israel Lanka Xiaohua Yang Jie Hao Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University of Sydney, Australia Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Essex, United Kingdom University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Catalina Neculai May Hongmei Gao Loredana Bosca University of Coventry, UK Kennesaw State University, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Anna Maria Constantinovici Marc Fetscherin AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Rollins College, USA Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Romona Mihaila Liu Chen Spiru Haret University, Romania Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Prof

Annual Report 1988-89 Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Prof. M. G. K. Menon inaugurating the Pelletron Accelerator Facility at TIFR on December 30, 1988. Dr. S. S. Kapoor, Project Director, Pelletron Accelerator Facility, explaining salient features of \ Ion source to Prof. M. G. K. Menon, Dr. M. R. Srinivasan, and others. Annual Report 1988-89 Contents Council of Management 3 School of Physics 19 Homi Bhabha Centre for Science Education 80 Theoretical Physics l'j Honorary Fellows 3 Theoretical A strophysics 24 Astronomy 2') Basic Dental Research Unit 83 Gravitation 37 A wards and Distinctions 4 Cosmic Ray and Space Physics 38 Experimental High Energy Physics 41 Publications, Colloquia, Lectures, Seminars etc. 85 Introduction 5 Nuclear and Atomic Physics 43 Condensed Matter Physics 52 Chemical Physics 58 Obituaries 118 Faculty 9 Hydrology M Physics of Semi-Conductors and Solid State Electronics 64 Group Committees 10 Molecular Biology o5 Computer Science 71 Administration. Engineering Energy Research 7b and Auxiliary Services 12 Facilities 77 School of Mathematics 13 Library 79 Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road. Colaba. Bombav 400005. India. Edited by J.D. hloor Published by Registrar. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road, Colaba. Bombay 400 005 Printed bv S.C. Nad'kar at TATA PRESS Limited. Bombay 400 025 Photo Credits Front Cover: Bharat Upadhyay Inside: Bharat Upadhyay & R.A. A chary a Design and Layout by M.M. Vajifdar and J.D. hloor Council of Management Honorary Fellows Shri J.R.D. Tata (Chairman) Prof. H. Alfven Chairman. Tata Sons Limited Prof. S. Chandrasekhar Prof. -

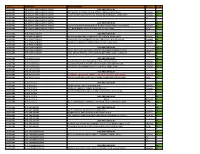

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA by GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA BY GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS. DEEPAK & HIMANI DALIA & ANOKHI, NIRALI & ANERI DALIA Previous 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI SATISH-KINNARY,AAKASH-PURVA-RIYAAN-NAIYOMI,BADAL-SONIA SHAH Previous 59 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI NA 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI VAIDYA RAMANBEN BHAKKAMBHAI TUSHAR DIMPLE HEMLATA PRABODH Gheeboli 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DR. CHANDRAKANT PRANLAL SHAH AND DEVYANI SHAH Raffle 46 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH DR.RASHMI DIPCHAND, CHANDRIKA, RAJU, MONA, HITEN GARDI Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH KERNEL,CHETNA,RAJA,MEENA,ASHISH,AMI,SHAILEE & SUJAL PARIKH Previous 58 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH NAGINDAS-VIJKORBEN, ARVIND-KIRAN, MANISH, ALKA SHAH Previous 51 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH ANISH, ANJALI, DULARI PARAG, MEMORY OF SHARDA MAFATLAL DOSHI Gheeboli 60 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH JYOTI PRADIP GRISHMA JUGNU SANYA PINKY MEHUL SAHIL & ARMAAN Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SURESH-PUSHPA, SNEHAL-RUPA & PARAG-TORAL BHANSALI Previous 49 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH KUSUM & DALPATLAL PARIKH FAMILY BY REKHA AND BIPIN PARIKH Previous 57 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH JAYANTILAL, NITIN-MEENA, MICHELLE, JESSICA, JAMIE SHAH Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH IN PARENTS MEMORY BY PARESH,LOPA,JATIN AND AMIT SHAH FAMILY Gheeboli 59 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SUSHILA-NAVIN SHAH AND FAMILY JAINIE JINESH PREM KOMAL KAJOL Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH DR.ANIL-BHARTI, RITESH & REEPAL SHAH Previous 36 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH ASHOK-DR. -

FT Pathshala Curriculum 2018-19.Xlsx

Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project Respect Teachers and Parents; Bhagwan and Chand Bow down to parents & elders; Pre-KG 1.Navkar Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Eight Kinds of Puja; 5 Khamasamna on kaushik, Past bhav of Bed time prayers (Shiyal Mara 3-4 3.Khamasamno 1st stanza 24 Tirthankar Names Gyan Pnchami Chand kaushik Santhare- Navkar tu maro bhai); Basic living non-living games How to hold Navkarvali; Goval Puts nails in Introduction to Jain Vocabulary Bhagvan's Ears; Due to like Jai Jinendra, Pranam, Pre-KG 2.Panchindiya Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Bhagvan's Karma During Bhagvan NavAngi 5 Khamasamna on Tirthankar, Puja, Aarti, Derasar, 4-5 4.Icchakar stanza 1 to 3 Tripristha Vasudev Bhav Puja Gyan Pnchami Upashray, Maharaj Saheb, (Putting Lead in Door Sadhviji etc.; Coloring and keeper's Ear) naming Lanchhans & Swapnas Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 4; Shrimate Virnathay; Siddharath 5.Abhuthio Mahavir Swami Nirvan, Sut Vandie Tirthankar Names and KG 6.Iriya vahiyam Gautam Swami Keval To Dehrasar Activity Book (Chaityavandan), Din Lanchhans 7.Tassa uttari gyan, Bhaibij Dukhiyano Tu chhe beli (Stavan), Mahavir Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 6; Kamathe Dharnendra, Jai 8.Anathha Parshwanath Bhagvan and Activity Book and Alphabets A to 1 Chintamani Parshwanath Guruvandan Vidhi To Dehrasar 9.Loggas Kamath M (Chaitya vandan), Tu Prabhu Maro (Stavan), Pas Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project -

Exploring Relationships Between Humans and Nonhumans in the Bishnoi Community

Sacred Trees, Sacred Deer, Sacred Duty to Protect: Exploring Relationships between Humans and Nonhumans in the Bishnoi Community Alexis Reichert A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MA degree in Religious Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Alexis Reichert, Ottawa, Canada 2015 ii Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ vi Introduction: Green Dharma ........................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Methodology: Beyond the Human ...................................................................................... 3 0.2 Theoretical Framework: Beyond the Nature/ Culture Dichotomy ..................................... 7 1. Themes of Kinship, Karma, and Monism: Review of the Literature ....................................... 12 1.1 Hinduism and Ecology: The Interconnectedness of Beings ............................................. 13 1.2 The Bishnoi: A Gap in the Literature .............................................................................. -

Century Old Jain Demand for Minority Status in India

CENTURY OLD JAIN DEMAND FOR MINORITY STATUS IN INDIA by BAL PATIL* The Jain demand for minority status is now a century old. When in British India the Viceroy took a decision in principle that the Government would give representation to "Important Minorities" in the Legislative Council, (Petition dt.2nd September,1909,)1 Seth Manekchand Hirachand, acting President of Bharatvarshiya Digambar Jain Mahasabha, thus appealed to the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, Lord Minto, for the inclusion of the Jain community as an Important Minority. The Viceroy responded positively to this petition informing that in giving representation to minorities by nomination the claim of the important Jain community will receive full consideration’. Seth Maneckchand’s Petition was transferred to the Government of Bombay and the Secretary to the Govt. Of Bombay stated in his reply dt.15th October,1909.2 “I am directed to inform you that a number of seats have been reserved for the representation of minorities by nominated and that in allotting them the claim of the important Jain Community will receive full consideration.” Presenting the Draft Constitution to the Assembly, Dr.Ambedkar warned against “fanaticism against minorities”.. (CAD p.766 ) We may hearken back to the crucial importance given to Minority safeguards in the Constituent Assembly Debates. The Resolution for the setting up of an Advisory Committee on Fundamental Rights, Minorities and Tribal and Excluded and Partically Excluded Areas clearly acknowledged that: “The question of minorities everywhere looms large in constitutional discussions. Many a constitution has foundered on this rock.. Unless the minorities are fully satisfied, we cannot make any progress: we cannot even maintain peace in an undisturbed manner.” And presenting the Draft Constitution to the Assembly Dr. -

Spelling God with Two O’S

Spelling God with Two O’s inspirational notes by Prof. Arthur Dobrin, DSW Hofstra University New York Hindi Granth Karyalay Mumbai 2009 Spelling God with Two O’s By Arthur Dobrin Mumbai: Hindi Granth Karyalay, 2009. ISBN 978-81-88769-39-1 Preface Life beckons. How will you respond? This is This book has been published in co-operation with the American Ethical Union the central message and question of Spelling God With Two O’s. Through quotations, questions, brief essays, HINDI GRANTH KARYALAY Publishers Since 1912 anecdotes, and parables, this book examines important 9 Hirabaug C P Tank values and themes of life. Spelling God With Two O’s Mumbai 400004 INDIA Phones: + 91 22 2382-6739, 2035-6659 presents a collage of thoughts that creates a meaningful philosophy by which to live. The basic point is that Email: [email protected] Web: www.gohgk.com compassion and social justice leads to a life filled with happiness. A good way to read Spelling God With Two First Edition: 2009 O’s is one chapter at a time. This gives you the opportunity to focus your attention and deepen your © Hindi Granth Karyalay insights. Each theme can serve as a daily meditation. Price: Rs. 195 I hope that you find this book a useful complement to your spiritual practice. When everyone Cover design by: AQUARIO DESIGNS Designer: Smrita Jain, [email protected] lives in the spirit of goodness, how is it possible for the world not to be a better place? Printed in India by Akruti Arts, Mumbai Ability Every person is responsible for all the good within the scope of his abilities, and for no more, and none can tell whose sphere is the largest.