UNEVERSETY Imre Tibbr Jarmy 1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17/2016 Sz. Értesítő

MLSZ FEJÉR MEGYEI IGAZGATÓSÁG Cím: 8000 Székesfehérvár, Honvéd u. 3/a. Fszt. Tel.: 06 (22) 312-282, Fax: 06 (22) 506-126 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.fmlsz.hu Adószám: 19020848-2-43 Bank: 11707024-20480772 Számlázási cím: 1112 Budapest, Kánai út 2/d. 17/2016. (05.25.) sz. Megyei Hivatalos Értesítő Versenybizottság határozatai 233/2015/2016. Az AGÁRDI TERMÁL Megyei II. osztályú U-19 bajnokság 28. fordulójában, a 2016. május 21. 10:00 órára kiírt Seregélyes – Soponya U-19 mérkőzés elmaradt. (Kódszám: 1115225) A mérkőzés 3 pontját 3:0 gólkülönbséggel a Versenybizottság a Seregélyes U-19 csapata javára rendeli el jóváírni. A határozatot a Versenybizottság az MLSZ Versenyszabályzat 57. §. (4) bekezdés alapján hozta meg. Mivel a Soponya U-19 csapata a bajnokság folyamán már negyedik alkalommal nem állt ki, ezért – az MLSZ Versenyszabályzat 58. §. (7) bekezdés d) pont alapján – a Versenybizottság a Soponya felnőtt csapatának évi összeredményéből három (3) büntetőpontot levon. Felhívjuk a Soponya SE vezetésének figyelmét, hogy az U-19-es csapat ötödik ki nem állása esetén – az MLSZ Versenyszabályzat 58. §. (7) bekezdés d) pontja szerint – a sportszervezet felnőtt csapatának évi összeredményéből három (3) büntetőpont kerül levonásra. 234/2015/2016. Az AQVITAL PUBLO Megyei III. osztályú bajnokság 22. fordulójában, a 2016. május 22-én 17:00 órára kiírt Lovasberény – Pátka II. bajnoki mérkőzésre a Pátka II. csapata 9 fővel jelent meg (Kódszám: 1114409). Ezért a Pátka II. felnőtt csapata ellen eljárást kezdeményezünk. A határozatot a Versenybizottság az MLSZ Versenyszabályzat 54. §. (4) bekezdése alapján hozta meg. Mivel a Pátka II. felnőtt csapata a bajnokság folyamán már harmadik alkalommal állt ki létszámhiányosan, ezért – az MLSZ Versenyszabályzat 54. -

Esettanulmányok Az Állami Földbérleti Pályázati Rendszer Értékeléséhez 1

Esettanulmányok az állami földbérleti pályázati rendszer értékeléséhez 1. Fejér megye Előzmények 2010 őszén 65 ezer hektár állami kezelésben lévő földterületen vált esedékessé a földbérleti szerződések pályázati úton történő megújítása . Ennek keretében első alkalommal nyílt lehetőség arra, hogy a 2010 nyarán az új Kormány által - a Földtörvényben és a Nemzeti Földalapról szóló törvényben - elsők között megfogalmazott birtokpolitikai irányelveknek megfelelően a helyben lakó gazdálkodó családoknak és a fiatal gazdáknak illetve a gazdálkodást, letelepedést és gyermekek világra hozatalát vállaló fiatal pároknak juttasson tartós bérlet keretében állami földterületeket. Az első nehézséget és feszültséget az okozta, hogy a 2010. szeptember 1-el ismét a VM irányítása alatt felálló Nemzeti Földalapkezelő Szervezet (a továbbiakban NFA) kaotikus állami földnyilvántartási viszonyokat örökölt. Ezért a Kormány egyszeri kényszer-megoldásként azt választotta, hogy újabb 1 évre szóló „termőföld hasznosításra irányuló megbízási szerződést” kötött a 2010. október 31-el lejáró földbérleti szerződésű és így felszabaduló területek megművelésére, többségében ugyanazokkal a gazdálkodókkal – zömében tőkés társaságokkal -, akik korábban is bérlői voltak a területeknek. Indulásnál tehát nem sikerült érvényt szerezni a kormányzó erők által már a választásokat megelőzően is széles körben meghirdetett és a magyar társadalom által igen kedvezően fogadott birtokpolitikai irányelveknek. Már ekkor, 2011 kora tavaszán megfogalmazódott azonban az a - később egyre erősödő -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

JEGYZŐK ELÉRHETŐSÉGEI (Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Megye)

JEGYZ ŐK ELÉRHET ŐSÉGEI (Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok megye) 2017.08.23 Közös önkormányzat JEGYZ Ő Sz. Ir. sz. Település neve, címe Önkormányzat web-címe települései megnevezése Név Telefon Fax e-mail címe Abádszalók, Dr. Szabó István 1. 5241 Abádszalók, Deák F. u. 12. Abádszalóki Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 59/355-224 59/535-120 [email protected] www.abadszalok.hu Tomajmonostora 2015.02.16-tól 2. 5142 Alattyán, Szent István tér 1. Tóth Ildikó 57/561-011 57/561-010 [email protected] www.alattyan.hu Berekfürd ő Kunmadarasi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Dr. Vincze Anita 3. 5309 Berekfürd ő, Berek tér 15. 59/519-003 59/519-002 [email protected] www.berekfurdo.hu Kunmadaras Berekfürd ői Kirendeltsége 2015.01.01-t ől Besenyszög Munkácsi György 56/487-002; 4. 5071 Besenyszög, Dózsa Gy. út 4. Besenyszögi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 56/487-178 [email protected] www.besenyszog.hu Szászberek címzetes f őjegyz ő 56/541-311 Cibakháza Török István [email protected]; 5. 5462 Cibakháza, Szabadság tér 5. Cibakházi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 56/477-001 56/577-032 www.cibakhaza.hu Tiszainoka 2016. július 1-t ől [email protected] Nagykör ű Nagykör űi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Szabó Szidónia 6. 5064 Csataszög, Szebb Élet u. 32. Csataszög 56/499-593 56/499-593 [email protected] www.csataszog.hu Csataszögi Kirendeltsége 2015.04.01-t ől Hunyadfalva Kunszentmárton Kunszentmártoni Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 7. 5475 Csépa, Rákóczi u. 24. Dr. Hoffmann Zsolt 56/323-001 56/323-093 [email protected] www.csepa.hu Csépa Csépai Kirendeltsége [email protected] 8. -

River Capacity Improvement and Partial Floodplain Reactivation Along the Middle-Tisza SCENARIO ANALYSIS of INTERVENTION OPTIONS

Integrated Flood Risk Analysis and Management Methodologies River capacity improvement and partial floodplain reactivation along the Middle-Tisza SCENARIO ANALYSIS OF INTERVENTION OPTIONS Date February 2007 Report Number T22-07-01 Revision Number 1_3_P01 Deliverable Number: D22.2 Actual submission date: February 2007 Task Leader HEURAqua / VITUKI FLOODsite is co-funded by the European Community Sixth Framework Programme for European Research and Technological Development (2002-2006) FLOODsite is an Integrated Project in the Global Change and Eco-systems Sub-Priority Start date March 2004, duration 5 Years Document Dissemination Level PU Public PU PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co-ordinator: HR Wallingford, UK Project Contract No: GOCE-CT-2004-505420 Project website: www.floodsite.net River capacity – Scenario analysis D22.2 Contract No:GOCE-CT-2004-505420 DOCUMENT INFORMATION River capacity improvement and partial floodplain reactivation along Title the Middle-Tisza – Scenario analysis of intervention options Lead Author Sándor Tóth (HEURAqua) Contributors Dr. Sándor Kovács (Middle-Tisza DEWD, Szolnok, HU) Distribution Public Document Reference T22-07-01 DOCUMENT HISTORY Date Revision Prepared by Organisation Approved by Notes 23/01/07 1.0 S. Toth HEURAqua 15/02/07 1.1 S. Kovacs M-T DEWD Sub-contractor 04/03/07 1.2 S. Toth HEURAqua 22/05/09 1_3_P01 J Rance HR Formatting for Wallingford publication ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The work described in this publication was supported by the European Community’s Sixth Framework Programme through the grant to the budget of the Integrated Project FLOODsite, Contract GOCE-CT- 2004-505420. -

List of Beneficiaries - FOP Priority Axis II

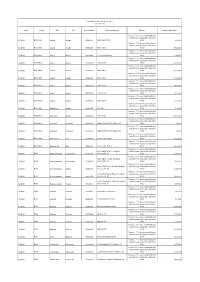

List of beneficiaries - FOP priority axis II. (1st June 2016) Region County Office Site Project identifier Name of beneficiary Measure Amount of support HUF Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1098982557 Szabó Róbert István fishery 7 268 549 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1099160437 Szabó József fishery 185 462 209 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1099219685 Czobor-Szabó Andrea fishery 12 491 533 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1220394092 Szabó József fishery 116 427 879 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1403233732 Szabó József fishery 121 133 947 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1534862007 Szabó József fishery 112 680 361 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1551073172 Szabó József fishery 14 565 813 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1697255443 Szabó József fishery 48 224 816 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1750982217 Szabó József fishery 21 641 331 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Dunatetétlen Akasztó 1624017586 Turu János fishery 7 153 285 Measure 2.1. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Orosz András Kör Állatorvos: Dienes Béla. Községi Orvos

Tiszakürt JÁSZ-NAGYKUN-SZOLNOK VÁRMEGYE Tiszaszentimre TISZAKURT. Gábor — Szőke Kálmán — Tó- Kocsmárosok: Borbély Eszter — szárostanya, Nagyház, Sülyi nagy- Hozzátartozik: Bogarasszöllő, vizi Károly. ifj. Dékány Sándor — Jakab major, Szentkirály, Tamáshát, Buzássziget. Cukrosszöllő, Cserke- Asztalos: Berkó István. Sándor — Keresk. és Iparosok Vallyóntelep, Virágoshát, Vörös és Perestanyák, Gőbölyjárás, Ho C ipészek: Farkas Mihály — Ma Köre — Kiss Károly — Pető m ajor. mok, Kisasszonypuszta, Kisasz- gyar Antal — Cs. Tóth György — Elek né — Polgári Olvasókör — Nk., jászsági alsó j., (székh.: szonyszöllö, Korhányszöllő, Ku- Cs. Tóth Im re — Cs. Tóth János. Pusztagyendai Hangya Szöv. — Jászapáti), 2585 1., rkat. fe, rázsszöllő, Mátévölgye, Muszály- Cséplögéptulajdonosok: Benedek Úri Kaszinó — Vas C József. 15.977 kh., tsz., püig.: Szolnok, szöllő. Nyárjas, Nyoinásszöllö, József — Benedek Márton — Mol Kovácsok: Borbély István — Far ib., adóhiv.: Jászapáti, & (mó öregszollő, Szigetmajor. Tópart. nár József — Péter Kálmán — kas Flórián — Farkas István — torhajó), -s- (fe i m (2i TíizesszÖllő, Villongószöllő. W indisch József. Jákl György — Márta Endre — km.) Jászladány. Fogyasztás! szöv.: Hangya. Nagy Sándor — Papp M. Gyula Községi biró: Zsérczi László Nk., tisza alsó j. (székh.: Ti- Hitelszövetkezet: xTiszapüspöki — özv. Pásztor Andrásné — Lengyel K. szafőldvár), 4367 1., ref. fe, 10.055 Vezető Jegyző: (O. K. H.) Szöv. Szabó János — Varga Sándor. Községi orvos: Bornemissza kh., tsz., püig.: Szolnok, jb., Kerékgyártók: Nagyidai József — Kőfaragó: Farkas Gusztáv. József. adóhiv.: Kunszentmárton, tít Ti- Szücs István. K őm űvesek: Bozóki József — Földbirtokosok: kk. Androjovits szakürt—Tiszainoka, Kovácsok: Mogyorós István — Cseppentő László — Deák Ferenc (15 km.) Homok. Orosz István — Vincze Pál — — Debreczeni Endre — Náhóczki Kázmér (112) — özv. Bakó Gé- Autóbuszjáratok: Kunszentm ár Vizi József. János. záné (236) — Balajthy Andorné ton—Tiszakürt, Szolnok—Tiszakürt Malomtulajdonos: Péter K. -

Lakossági Tájékoztató Tordas-Velence Kerékpárút

LAKOSSÁGI TÁJÉKOZTATÓ BUDAPEST-BALATON KERÉKPÁROS ÚTVONAL – TORDAS-VELENCE RÉSZSZAKASZ ÉPÍTÉSE A beruházó NIF Nemzeti Infrastruktúra Fejlesztő Zrt. megbízásából a SWIETELSKY Magyarország Kft. kivitelezésében valósul meg a Budapest-Balaton kerékpáros útvonal, Etyek-Velence szakaszán belül a Tordas-Velence részszakasz kiépítése. A beruházás 5 települést érint: Tordas, Kajászó, Pázmánd, Nadap, Velence. A szakasz eleje a tordasi Csillagfürt lakókert bejáratánál csatlakozik az Etyek-Tordas közötti szakaszhoz és a mintegy 17,5 km egybefüggő hosszan vezető nyomvonal Velencén, a meglévő part menti kerékpárúthoz történő csatlakozással ér véget. A projekt ismertetése: 1. TORDAS A szakasz, illetve a projekt kezdőszelvénye Tordason, a Köztársaság úton a Csillagfürt lakókert bejáratánál található, és Tordas közigazgatási határáig 1104 méter hosszon 3,5 m szélességben vezet, melynek kialakítása a meglévő földút burkolásával és forgalomtechnikai jelzések elhelyezésével történik. 2. KAJÁSZÓ Kajászó közigazgatási területén a tordasi szakasz folytatásaként, a meglévő mezőgazdasági út szilárd burkolattal történő ellátásával és a forgalomtechnikai jelzések elhelyezésével a nyomvonal az Ady Endre utcába való csatlakozásig folytatódik. A szakasz hossza 1175 méter, a mezőgazdasági út hasznos szélessége 3,5 méter. Kajászó lakott területén a Rákóczi utca – Kossuth utca nyomvonalában, mintegy 922 méter hosszon forgalomtechnikai elemek kel kerül kialakításra a kerékpáros útvonal. A Rákóczi utca – Kossuth utca csomópontjában új gyalogátkelőhely és kerékpáros- átkelőhely épül. Kajászó lakott területén kívül, a Kossuth utca folytatásában a meglévő földút burkolása valósul meg. A mezőgazdasági út hossza 3148 m, hasznos szélessége 3,5 méter. 1 LAKOSSÁGI TÁJÉKOZTATÓ BUDAPEST-BALATON KERÉKPÁROS ÚTVONAL – TORDAS-VELENCE RÉSZSZAKASZ ÉPÍTÉSE 3. PÁZMÁND Pázmánd közigazgatási területén a kajászói burkolt mezőgazdasági úthoz csatlakozva 3096 méter hosszú, szilárd burkolatú mezőgazdasági ut at alakítanak ki 3,5 méter szélességben. -

B Alm Azú Jvárosi K Istérség

Gyermekjóléti szolgáltatások címjegyzéke 2009. Ssz. Település megnevezése Intézmény neve, címe, vezet ı neve, Gyermekjóléti szolgáltatás Dolgozók neve, Mőködési engedéllyel kistérségenként elérhet ısége vezet ıjének neve, elérhet ısége elérhet ısége kapcsolatos adatok 1. Balmazújváros Balmazújvárosi Kistérség Gyermekjóléti Szolgálat 4060 Balmazújváros , Kiadás ideje: 2005. 11. Hortobágy, Családsegít ı és Gyermekjóléti Kossuth tér 3. 02. Egyek, Szolgálata 4060 Balmazújváros, Kossuth tér Családgondozók: Eljáró hatóság: Tiszacsege 3. Erdeiné Gy ıri Csilla, Hajdúböszörmény 4060 Balmazújváros, Kossuth tér 3. Kapusiné Dobi Anett, Száma: 5037-24/2005., Figéné Nádasdi Ágnes Györfiné Kis Julianna, 5037-26/2005. (mód) Juhászné Kányássy Katalin Bugjóné Szabó Mária, Tel.: 52/580-597, 52/580-598, Pszichológus: Balmazújvárosi Kistérség Kistérség Balmazújvárosi Tel.: 52/580-597 52/580-599 Kis Mónika (heti 20 óra Fax: 52/580-598 Fax: 52/580-598 minden település) E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Hortobágy , Kossuth u. 8. Tel.: 52/589-356 Családgondozó: Cs ıke Lászlóné (20 óra) Egyek , F ı tér 23. Tel.: 52/378-344 Családgondozók: Szabóné Balázs Erika, Fehér Béláné Tiszacsege , F ı u. 42. Tel.: 52/373-598 Családgondozók: Vásári Orosz Andrea, Kovács Viktória 2 Ssz. Település megnevezése Intézmény neve, címe, vezet ı neve, Gyermekjóléti szolgáltatás Dolgozók neve, Mőködési engedéllyel kistérségenként elérhet ısége vezet ıjének neve, elérhet ısége elérhet ısége kapcsolatos adatok 2. Berettyóújfalu* Városi Szociális Szolgáltató Központ Gyermekjóléti Szolgálat Berettyóújfalu , Kiadás ideje: 2006. 01. Szentpéterszeg, Kossuth u. 6. 31-tól határozatlan id ıre Gáborján, 4100 Berettyóújfalu, Kossuth u. 6. 4100 Berettyóújfalu, Kossuth u. Családgondozók: szól Hencida, 6. Szabóné Kovács Eljáró hatóság: Derecske Esztár, Varga Józsefné Zsuzsanna, Lele Száma:7002-9/2006. -

Ethnical Analysis Within Bihor-Hajdú Bihar Euroregion

www.ssoar.info Ethnical analysis within Bihor-Hajdú Bihar Euroregion Toca, Constantin Vasile Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Toca, C. V. (2013). Ethnical analysis within Bihor-Hajdú Bihar Euroregion. In M. Brie, I. Horga, & S. Şipoş (Eds.), Ethnicity, confession and intercultural dialogue at the European Union's eastern border (pp. 111-119). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publ. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-420546 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use.