False Starts| a Collection of First Chapters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Resumes

REPORT RESUMES ED 019 218 88 SE 004 494 A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES, K-6. LINCOLN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, NEBR. PUB DATE 67 EDRS PRICEMF.41.00 HC-S10.48 260P. DESCRIPTORS- *ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *PHYSICAL SCIENCES, *TEACHING GUIDES, *SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *SCIENCE ACTIVITIES, ASTRONOMY, BIOGRAPHIES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, FILMS, FILMSTRIPS, FIELD TRIPS, SCIENCE HISTORY, VOCABULARY, THIS RESOURCE BOOK OF ACTIVITIES WAS WRITTEN FOR TEACHERS OF GRADES K-6, TO HELP THEM INTEGRATE AEROSPACE SCIENCE WITH THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES OF THE CLASSROOM. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE FOR INTRODUCING AEROSPACE CONCEPTS INTO THE VARIOUS SUBJECT FIELDS SUCH AS LANGUAGE ARTS, MATHEMATICS, PHYSICAL EDUCATION, SOCIAL STUDIES, AND OTHERS. SUBJECT CATEGORIES ARE (1) DEVELOPMENT OF FLIGHT, (2) PIONEERS OF THE AIR (BIOGRAPHY),(3) ARTIFICIAL SATELLITES AND SPACE PROBES,(4) MANNED SPACE FLIGHT,(5) THE VASTNESS OF SPACE, AND (6) FUTURE SPACE VENTURES. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE THROUGHOUT FOR USING THE MATERIAL AND THEMES FOR DEVELOPING INTEREST IN THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES BY INVOLVING STUDENTS IN AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES. INCLUDED ARE LISTS OF SOURCES OF INFORMATION SUCH AS (1) BOOKS,(2) PAMPHLETS, (3) FILMS,(4) FILMSTRIPS,(5) MAGAZINE ARTICLES,(6) CHARTS, AND (7) MODELS. GRADE LEVEL APPROPRIATENESS OF THESE MATERIALSIS INDICATED. (DH) 4:14.1,-) 1783 1490 ,r- 6e tt*.___.Vhf 1842 1869 LINCOLN PUBLICSCHOOLS A RESOURCEBOOK OF AEROSPACEACTIVITIES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION K-6) THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. 1919 O O Vj A PROJECT FUNDED UNDER TITLE HIELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION ACT A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES (K-6) The work presentedor reported herein was performed pursuant to a Grant from the U. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

CARAWAN-THESIS-2016.Pdf (1.112Mb)

DEDICATION I would like to thank the members of my Graduate Committee, my family, and my friends. A FAMILY BEREAVEMENT CAMP AND EMERGING THEMES 1 A FAMILY BEREAVEMENT CAMP: EMERGING THEMES REGARDING ITS IMPACT ON THE LIVES OF BEREAVED PARENTS AND SIBLINGS by MELISSA ANNE CARAWAN THESIS PROPOSAL Presented to the Faculty of the School of Health Professions The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas, Texas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF CLINICAL REHABILITATION COUNSELING A FAMILY BEREAVEMENT CAMP AND EMERGING THEMES 2 Copyright © 2015 by MELISSA ANNE CARAWAN All Rights Reserved A FAMILY BEREAVEMENT CAMP AND EMERGING THEMES 3 Abstract BACKGROUND: Within the grief literature, family bereavement camps have yet to be researched in a combined population of bereaved parents and siblings. Camp Sol is a weekend retreat for families who have experienced the death of a child/sibling. The goal of the current study is to establish areas reported by parents and sibling campers as being impacted by their experience at camp in hopes of identifying standardized measures that can be implemented in the future evaluation process. This will provide future researchers the ability to quantitatively evaluate the overall efficacy of a family bereavement camp among bereaved parents and siblings. SUBJECTS: Camp Sol evaluations were collected post-camp over the span of five and a half years totaling 656 evaluations. Parents comprised 50.2% of the sample, where the majority of them spoke English versus Spanish (81.4% vs. 18.5%). The children comprised 49.8% of the sample and ranged from the age of 4 to 19. -

Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-20-2013 12:00 AM Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism Andrew C. Wenaus The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Jonathan Boulter The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Andrew C. Wenaus 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Philosophy of Mind Commons Recommended Citation Wenaus, Andrew C., "Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1512. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1512 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Andrew C. Wenaus Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Andrew C. Wenaus 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation contributes to the critical expansions now occurring in what Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. -

Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University 1983 The undF amentalist Journal 7-1983 Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83 Recommended Citation "Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7" (1983). 1983. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The undF amentalist Journal at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1983 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUNDAI"IENTALI.ET One Dollqr & Ninety-Five Cents JOUPNAL Jtrly/August 1983 OneNation underGod on the Rebound The Churchand Her Rights The Christian Churchunder Communism America WakeUp! I .r'-, v |<(,*,, ! {, ()L/ ( I {! t1 v *'e ';;il l-,rl llL. (; c:h:r{r "rj Fr It U, j/ e/ +- -<-r-o z,o 3,;S L <-l Fj (^l o3 i" t' f.l cm ::r !^-.,.. a^ uci r! tJ , -o aq; -a ,i >! iJ.l vm a*j Nt- 5T T Have you ever wondered why Christians are usually portrayed unsympatheticallyon TV and in movies? . Why our childrenare learning anti- Christiarrmoral valuesin public schools? . Why so few Christianbooks.rre in your localbookstore and library-even when they are bestsellers? V,lhy? Bacnusethcrc's {t ttcTLtlt)ltltc of cettsorshilt sTLteepifigArtrcrica. No, it's not the obvious kind that actuallybr-rrns books. It's somethirrg much more subtle-and more effective. The real censorstodav are hard-coresecu- laristswhtl hold the p.,siti.,nsof influence in education,the media, and public life. -

The Odyssey, Book One 273 the ODYSSEY

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

Lamb in His Bosom / Caroline Miller ; Afterword by Elizabeth Fox-Genovese

Lamb inHis Bosom 1934 Pulitzer Prize Winner for the Novel Lamb inHis Bosom CAROLINE MILLER with an Afterword by Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 1933, 1960 by Caroline Miller All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photo- copy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Loraine M. Joyner Book design and composition by Melanie McMahon Ives Manufactured in August 2011 by RR Donnelley & Sons, Harrisonburg, VA in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 This book was originally published in 1933 by Harper & Brother’s Publishers Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miller, Caroline Pafford, 1903– Lamb in his bosom / Caroline Miller ; afterword by Elizabeth Fox-Genovese. p. cm. — (Modern southern classics series) ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-074-? / ISBN 10: 1-56145-074-X 1. Frontier and pioneer life—Georiga—Fiction. 2. Georgia —History— Fiction. I. Title. II. Series. PS3525.I517L3 1993 813’.52—dc20 92-38286 CIP For Wi’D and little Bill and Nip ‘n’ Tuck Chapter1 EAN turned and lifted her hand briefly in farewell as she rode away beside Lonzo in the ox-cart. Her mother and Cfather and Jasper and Lias stood in front of the house, watch- ing her go. The old elder who had married Cean to Lonzo was in the house somewhere, leaving the members of the family to them- selves in their leave-taking of Cean. -

The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992

China’s Second World of Poetry: The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992 by Michael Martin Day Digital Archive for Chinese Studies (DACHS) The Sinological Library, Leiden University 2005 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................4 Preface …………………..………………………………………………………………..7 Chapter 1: Avant-Garde Poetry Nationwide – A Brief Overview ……………..……18 Chapter 2: Zhou Lunyou: Underground Poetry during the 1970s ………………… 35 Chapter 3: The Born-Again Forest : An Early Publication …………….…………….46 Chapter 4: Macho Men or Poets Errant? ……………………………………………..79 Poetry on University Campuses………………………………………….79 A Third Generation………………………………………………………82 Hu Dong, Wan Xia, and Macho Men……………………………………88 Li Yawei………………………………………………………………….99 Ma Song………………………………………………………………...103 Finishing with University………………………………………………107 Chapter 5: A Confluence of Interests: The Institution of the Anti-Institutional ….114 Setting the Scene………………………………………………………..114 The Establishment of the Sichuan Young Poets Association…………..123 The First Product of the Association: Modernists Federation………….130 Chapter 6: The Poetry of Modernists Federation ……………………………………136 Chapter 7: Make It New and Chinese Contemporary Experimental Poetry ….…..…169 Growing Ties and a Setback……………………………………………170 Day By Day Make It New and the Makings of an Unofficial Avant-Garde Polemic…………....180 Experimental Poetry : A Final Joint Action…………………………….195 Chapter 8: Moving into the Public Eye: A Grand Exhibition -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

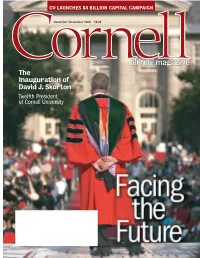

Alumni Magazine the Inauguration of David J

c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 2:22 PM Page c1 CU LAUNCHES $4 BILLION CAPITAL CAMPAIGN November/December 2006 $6.00 alumni magazine The Inauguration of David J. Skorton Twelfth President of Cornell University c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page c2 c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page 1 002-003CAMND06toc 10/16/06 3:45 PM Page 2 Contents NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2006 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 3 4 Letter From Ithaca alumni magazine French toast Features 6 Correspondence Natural selection 10 From the Hill The dawn of the campaign. Plus: Milstein Hall 3.0, meeting the Class of 2010, the ranking file, the Creeper pleads, and a new divestment movement. 16 Sports A rink renewed 18 Authors The full Marcham 35 Finger Lakes Marketplace 52 44 Wines of the Finger Lakes 46 In Our Own Words 2005 Lucas Cabernet Franc CAROL KAMMEN “Limited Reserve” To Cornell historian Carol Kammen, 62 Classifieds & Cornellians the unheard voices in the University’s in Business story belong to the students them- selves. So the senior lecturer dug into 65 Alma Matters the vaults of the Kroch Library and unearthed a trove of diaries, scrap- books, letters, and journals written by 68 Class Notes undergraduates from the founding to 109 the present.Their thoughts—now 46 assembled into a book, First-Person Alumni Deaths Cornell—reveal how the anxieties, 112 distractions, and preoccupations of students on the Hill have (and haven’t) changed since 1868.We offer some excerpts. Cornelliana Authority figures 52 Rhapsody in Red JIM ROBERTS ’71 112 The inauguration of David Skorton